The 1st July 1972 saw something special: the first UK Pride march (see footnote 1). The previous two years had seen small-scale marches, but this was different – this was the first march billed as Gay Pride. From this time onwards Pride parades have continued, and Pride in London now draws crowds of millions.

At the Pride march in 1972, approximately 300 to 1,000 people (footnote 2) marched down Oxford Street to Hyde Park to make their political point. Early photos of Pride parades show participants carrying placards with phrases such as ‘homosexuals are revolting’ and ‘we demand the right to show affection in public’. The date was inspired by the 1969 Stonewall Riots in America – and the first American Pride march in 1970 – being the closest Saturday date to both of these anniversaries.

The 1972 Pride march had been organised by the Gay Liberation Front – a short-lived but powerful political organisation that fought for lesbian and gay equality. These early Pride parades were centred on political goals, often drawing directly on the manifestos of organisations behind the parades (footnote 3). Pride marches were just one of the many political activities engaged in at this time, alongside Gay Weeks, think-ins, kiss-ins and other protests. This shift towards an open sense of pride was significant; in the previous decades and centuries same-sex relationships had been seen through largely moral, medical and criminal lenses.

Archive Pride collections

Many archival collections hold items about these wonderful early Pride marches. The National Archives, on the other hand, holds very few records about UK Pride marches and nothing about these early parades. The little we do have tends to relate to government employees participating in Pride parades from the 2000s (these can be found on the government web archive). We hope to get more records about Pride marches over time.

Collections that do hold items about Pride include:

- The Hall Carpenter Archives at the London School of Economics Library, Archives and Special Collections.

- The London Metropolitan Archives, who have digitised photos as part of their Speak Out project.

- Islington Archives, who have records predating formal Gay Pride marches. November 1970 saw a march of 150 people through Highbury Fields in North London.

- Bishopsgate Institute Archives and Special Collections – gallery on the Gay Liberation Front and Pride.

The National Archives collections tend to be strongest on items on the pre-partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967 (in England and Wales). To protest openly was not easy before this time; there was great risk involved. Indeed, one of the key campaigning organisations in this era was the Homosexual Law Reform Society (HLRS), formed in 1958, which often used behind the scenes lobbying and strongly relied on heterosexual allies to push for a change in the law.

Despite the difficulty in protesting, there are clear indications of pride and defiance in the decades before these marches and liberation campaigns materialised. This blog post will explore moments of inspiring, everyday queer defiance in our collections.

The Caravan Club

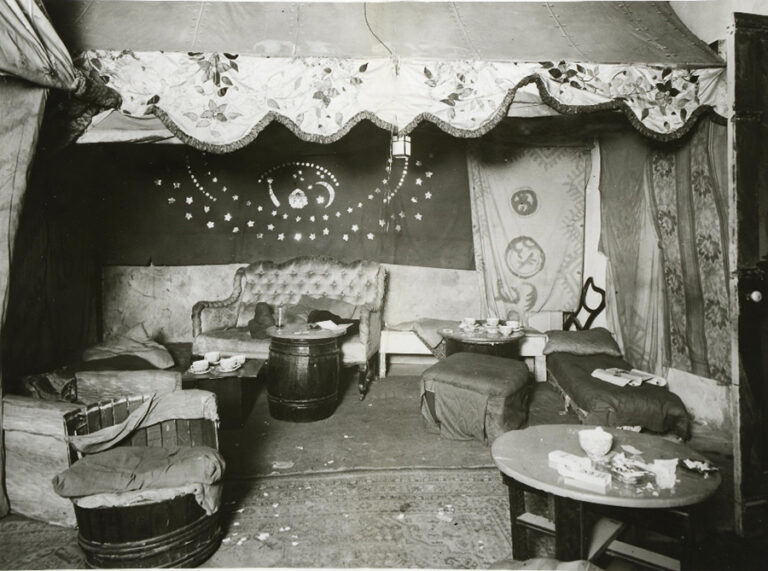

The very existence of clubs and spaces before partial decriminalisation was an act of defiance. LGBTQ+ people needed places to meet, which drove demand for clubs such as the Caravan Club. Opened in 1934, the Caravan Club was a bohemian private members bar, known as ‘the most unconventional spot in town’, that enabled same-sex couples to socialise, dance and have sexual encounters. The venue was one of a network of clubs and spaces in 1930s London that cultivated a queer clientele.

Ultimately the venue was raided by police officers.

During the raid one of the attendees, Cyril de Leon, approached the inspector in an extraordinary act of resilience:

‘Well I don’t mind this beastly raid, but I would like to know if you can let me have one of your nice boys to come home with. I am really good.’

Catalogue ref: DPP 2/224

It seems that these defiant spaces bred a rebellious attitude too. To speak back to, and even jokingly flirt with the very police who were enforcing the criminalisation of your sexuality, was certainly a bold move.

A few years later in a raid on a drag dance at Holland Park Ballroom, an individual called Lady Austin defended the dance to the police: ‘Before long our cult will be allowed in this country and we shall then vindicate our patron saint the glorious Oscar Wilde’. (footnote 4)

Lister and Walker

Alternatively, in the early 19th century the lovers Anne Lister and Ann Walker defied the conventions of the time by uniting through an act they saw as marriage.

The couple’s options to show each other their mutual dedication and love were limited, after all this was centuries before civil partnerships and same-sex marriage were possible. To illustrate their shared commitment, on Easter Sunday 1834 in Holy Trinity Church, Goodramgate they took communion together as an act of marriage. Two hundred years on, the church now bears a plaque acknowledging the sacrament they took together to seal their union.

A dog called Sappho

The Ladies of Llangollen – Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby – were two upper class women from Ireland who ran away together to Llangollen, Wales. The nature of their relationship was questioned throughout their lifetime, and is still debated today. Were they friends, or lovers? In our records we can see the pair’s wills. In her will Eleanor refers to Sarah as her ‘Beloved friend’.

The couple were bold in their own way in their lifetime; wearing unconventional clothes, cultivating a unique circle of friends and admirers, and even calling multiple dogs Sappho (arguably a definite hint to the nature of their relationship …), the couple were also buried together, along with their faithful friend and servant, Mary Carryl.

Against the law

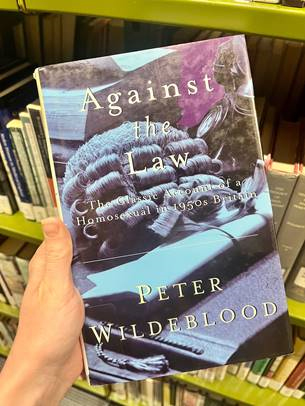

In the 1950s Peter Wildeblood, diplomatic correspondent for the Daily Mail, went public about his sexuality. In 1952 Wildeblood had been arrested and prosecuted for homosexual acts with RAF servicemen, alongside Lord Montagu of Beaulieu and Michael Pitt-Rivers. Their subsequent prison sentences (ranging from 15 to 18 months) were perceived as unduly harsh. In court Wildeblood had spoken openly about his sexuality and after his release from prison published his memoir, ‘Against the Law’.

Following this, Wildeblood became one of only three openly homosexual men to submit evidence to the Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution, better known as the Wolfenden Committee. Wildeblood’s testimony to the Wolfenden Committee, held in our collections, was influential on its recommendations. The resulting Wolfenden Report endorsed the partial de-criminalisation of homosexual acts, which was eventually implemented in 1967 in England and Wales, giving gay and bisexual men greater freedoms.

Everyday pride and defiance

In this blog I have focused on acts of pride and defiance by picking out key moments in our records. However, just continuing to live your life, to meet and love, in a time that criminalised or supressed your sexuality, was also an act of resistance. We can see this in the 1921 Census which features the many LGBTQ+ individuals who continued to live with their partners and, at times, live their gender identities openly.

If you are at a Pride event this month, remember the history that led to these parades; celebrate loudly and boldly for those who couldn’t be as open in their lifetimes.

Footnotes

- This blogpost uses LGBTQ+ as an umbrella term to describe lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer people across a variety of time periods. The post also uses terms such as gay and queer, when in keeping with the language of the time being spoken about. For more context around language and LGBTQ+ history, refer to The National Archives’ guidance on Sexuality and gender identity history.

- The exact number is disputed. No Bath but Plenty of Bubbles, An Oral History of the Gay Liberation Front 1970-1973 by Lisa Power, suggests up to 1000 people were present of all GLF fractions.

- Gay Liberation Front demands, HCA GLF 1, LSE Archive and Special Collections.

- Salmon, Austin and (33) others. Charge: Conspiracy to corrupt morals, keeping disorderly house. 1933. Catalogue ref: CRIM 1/639.

It is just untrue about the decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967, this only applied to England and Wales (Scotland had to wait until 1981).