Given the extraordinary and unsettling situation of the past two years, it has been important to find solace and distraction wherever possible. For me, this was making a list of places I wanted to visit when we were able to do so again. In the midst of the lockdowns the mere thought of travel became a real novelty, and I’m sure I’m not alone in saying I took for granted the ease at which we were previously able to travel the world.

But one good thing came out of this awful time: the opportunity to explore places closer to home. I discovered that within these places, as beautiful or as interesting as they are, it is the people and their stories that often bring a place to life, and so I introduce you to Plas Newydd and the story of its owners: Lady Eleanor Butler and Miss Sarah Ponsonby – The Ladies of Llangollen.

Lady Eleanor Butler was born in France in 1739, while Miss Sarah Ponsonby was born in Ireland in 1755. They met in 1768 after Eleanor had returned to her family home at Kilkenny Castle, and Sarah, who had become an orphan at the age of 13, was now living with her father’s cousin, Lady Elizabeth ‘Betty’ Fownes, in County Kilkenny.

Sarah and Eleanor met during Sarah’s time at school. Betty had asked Eleanor’s mother to keep an eye on Sarah – a task she delegated to her daughter. Eleanor and Sarah developed a close friendship, which continued throughout Sarah’s schooling days.

When Sarah turned 18 and returned home, the pair stayed in touch and remained close friends, confiding in each other about their similar situations. Both women were being pressured to marry and there was mention of Eleanor being sent to a convent. Sarah also found herself in a very uncomfortable situation – it was William Fownes’ intention to marry Sarah on the death of his ailing wife, Betty. Sarah found this proposition appalling; to her it would have been a betrayal of Betty’s generosity and kindness.

Eventually, determined not to conform to the pressures of society, Eleanor and Sarah decided they would run away and set up a life together. And that’s exactly what they did on the night of 30 March 1778. The pair, dressed in men’s clothing and armed with a pistol, made their way to Waterford where they intended to catch a boat to Wales. However, their families discovered their plan and found them hiding near Waterford dock; some say that it was the incessant barking of Sarah’s dog, Frisk (who they had taken with them), who had given them away.

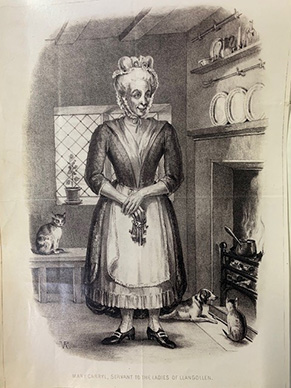

After this failed escape attempt both women, clearly miserable and still determined to leave, finally got their wish. Realising that Eleanor and Sarah weren’t going to change their minds, their respective families gave in. And so, a couple of months later, in May the two left Ireland and travelled by sea to Wales. They were accompanied by a servant from Sarah’s household, Mary Carryl, who remained a faithful servant and friend for the rest of her life. Accounts of Mary’s character are rather colourful – it’s rumoured she was dismissed from Woodstock for throwing a candlestick at a fellow servant. An entry in Eleanor’s diary describes how Mary would give as good as she got as she bargained loudly with the fishermen, the butchers and the inebriated.

After several months of travelling around Wales, Eleanor and Sarah arrived in the small Welsh valley of Llangollen, where they set up home in (as it was then) a rather poor-looking farm house. The aptly named Plas Newydd (New House) became the place for their new life together and would remain their home for 50 years.

In the words of Anne Lister (aka Gentleman Jack):

‘I should not like to live in Wales – but if it must be so, and I could choose the spot, it should be Plas Newydd at Llangollen, which is already endeared even to me by the association of ideas.’

Anne Lister (The Secret Diaries of Miss Anna Lister, edited by Helena Whitbread)

This ‘association of ideas’ relates to the life Eleanor and Sarah built together over time, a life that Anne Lister, and others, were keen to build for themselves – a life outside of the 18th-century norm for women. Reading Lister’s diary entries we learn that she had accepted her own sexuality and was already exploring sexual relationships with women, but she understood the unlikelihood of finding a woman who felt the same way, someone who would be prepared to sacrifice everything to live with her as a true partner. The ladies offered Lister a glimmer of hope, but while it’s a nice idea that the ladies were in love, this is something that Eleanor and Sarah vehemently denied.

As you approach Plas Newydd (it now consists of only the main building shown in the photograph above), you are met with a smart, almost symmetrical-looking house, set among beautifully manicured gardens. It’s not until you get closer that you are treated to the intricate magnificence of the porch made of oak.

And it doesn’t end there. The oak panelling continues through the cottage, winding its way up the staircase. Their heavy use of oak seems inspired by the Gothic revival style. Many locals and guests to Plas Newydd donated old pieces of oak to the ladies; they knew the ladies would greatly appreciate such a gift. When you look closely you realise the panelling is a giant collage made up of parts of old cupboards, beds, chests, church pews, chair backs, bosses and bed posts. By putting all these separate elements together, Eleanor and Sarah have in effect created a wonderful giant oak jigsaw. The pair of lions that have pride of place in their porch are said to have been gifted by Lord Wellington.

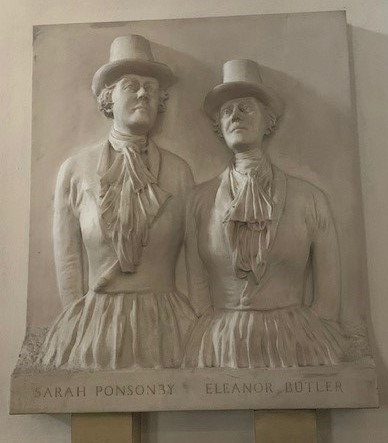

As I entered the cottage, I spied a couple of top hats hanging on the wall. The ladies were known for their masculine attire – they often donned a top hat and riding habits. The mere presence of the hats managed to evoke a feeling of homeliness; it was almost as if the ladies had popped out, leaving me the opportunity to explore their home. Although some of the interior (end exterior) has been altered over the years, I could still very much feel their presence. I could easily imagine them pottering about the place or reading to each other by the fire.

Eleanor and Sarah were keen to live a quiet, secluded life. They were both well-educated, spoke French and loved literature, so they were perfectly happy spending time reading and writing. Eleanor and Sarah were keen letter-writers and they kept diaries, many of which are kept at The National Library of Wales and other archives in the UK. They also loved spending time working on their garden, and making improvements and alterations to Plas Newydd.

The elaborate style and decoration of their home, and the ladies themselves, attracted many visitors – a number of whom were notable figures of the day, such as Sir Walter Scott, Wordsworth, Charles Darwin and his father, Shelley, Byron and even the wife of the Prince of Wales, Princess Charlotte, as well as the Duke of Wellington. Literary guests found inspiration at Plas Newydd, and some published poems and accounts from their visits. Wordsworth famously wrote the following poem:

To Lady Eleanor Butler and the Honourable Miss Ponsonby,

Composed in the grounds of Plas-Newydd, Llangollen

A stream to mingle with your favorite Dee

Along the Vale of Meditation flows;

So styled by those fierce Britons, pleased to see

In Nature’s face the expression of repose,

Or, haply there some pious Hermit chose

To live and die — the peace of Heaven his aim,

To whome the wild sequestered region owes

At this late day, its sanctifying name.

Glyn Cafaillgaroch, in the Cambrian tongue,

In ours the Vale of Friendship, let this spot

Be nam’d, where faithful to a low roof’d Cot

On Deva’s banks, ye have abode so long,

Sisters in love, a love allowed to climb

Ev’n on this earth, above the reach of time.

Despite their wish to be left alone, the ladies were happy to welcome and entertain their guests. The ladies appeared to be well-liked and respected within the community and nobody seemed particularly concerned by their relationship.

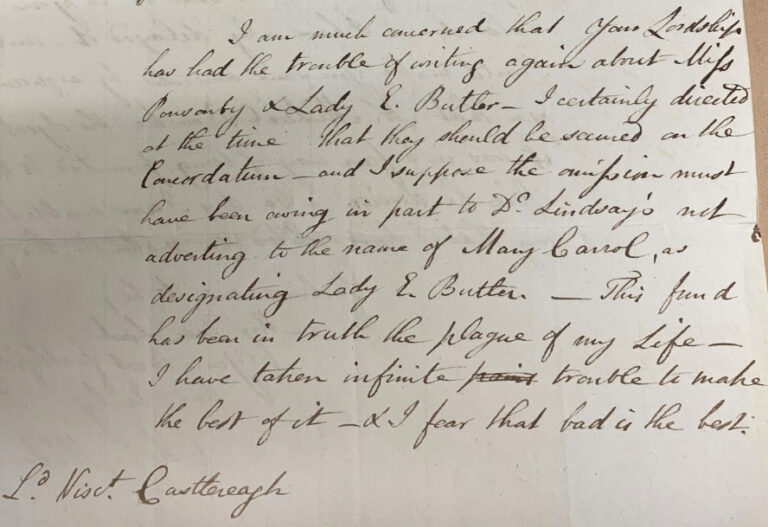

You may wonder how Eleanor and Sarah were able to finance this lifestyle. While both came from wealthy backgrounds, their relatives were still displeased with their decision to leave Ireland and set up home together. They certainly were not prepared to keep them in the lap of luxury; however, the families did agree to provide them with a small allowance. In addition to this, over the years, they borrowed money, relied on donations from friends and relatives, and received what appears to be some sort of government funding. The National Archives holds a letter from Lord Castlereagh (MP) regarding a grant from the Commendatum Fund:

‘I am much concerned that your lordship has had the trouble of writing again about Miss Ponsonby and Lady E Butler – I certainly directed at the time that they should be secured on the condordatum – and I suppose the confusion must have been owing in part to Dr Lindsay’s not adverting to the name of Mary Carrol, as designating Lady E Butler – This fund has been in truth the plague of my life – I have taken infinite trouble to make the best of it – and I fear that bad is the best. Dr Lindsay has become our almoner, and to his care I have turned over the details, after settling the plan of the principle.’

It has also been suggested that Princess Charlotte secured them a small pension, and after Eleanor’s death the Duke of Wellington granted Sarah a pension of £200 a year on the Civil List.

So it seems the ladies were not rich. They had to watch what they spent and from accounts I have read they led quite a simple life. However, their money matters seem to be contradictory; on one hand, to keep living costs down they kept a cow for milk and butter to supplement their income, but on the other hand they had enough money to employ a maid, a footman, a cook and a gardener, so I suppose by most people’s standards they were reasonably well-off.

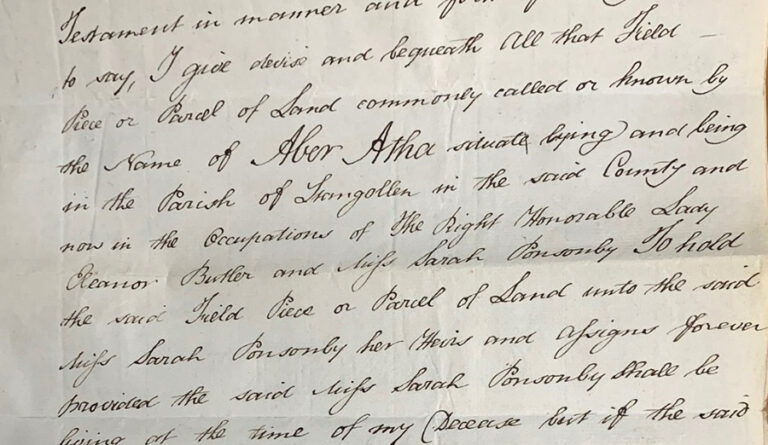

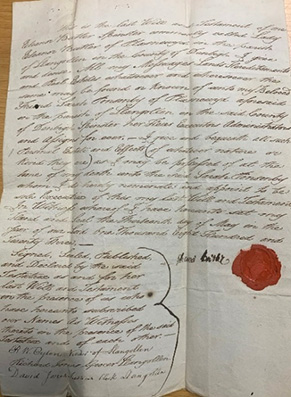

After many happy years living together their situation took a sad turn in 1809, when their faithful servant and friend, Mary Carryl, passed away. Over the years Mary had saved enough money to buy a piece of land in Llangollen. Mary wrote a will in which she left the plot of land, Aber Atha, to Sarah Ponsonby.

The ladies held Mary in such high regard that when she died, they erected a three-sided monument – a sacred place that would be the final resting place for the three of them.

Twenty years later, in 1829, Eleanor passed away and, as one would expect, Plas Newydd is left to Sarah. In her will Eleanor refers to Sarah as her ‘Beloved friend’.

On Sarah’s death in 1831, Plas Newydd is left to her nephews who, not long after, put it up for sale. And there ends the story of Lady Eleanor Butler and Miss Sarah Ponsonby, as inscribed on Sarah’s side of the monument:

– but they

shall no more return to their House neither shall

their place know them any more.

Job, Chap. 7, V.10.

I wonder if Eleanor and Sarah realised the impact their relationship would have, not only on those at the time but also on generations to follow? The ladies were already living through a time of great change; the Industrial Revolution was transforming lives and economies. In their own small way, the ladies were inadvertently contributing to this period of change. Their brave and tenacious personalities enabled them to push against the restraints and expectations of what a woman’s life could and should be; a fight that would be furthered by the many women campaigners through the following centuries.

People may continue to debate the nature of Eleanor and Sarah’s relationship, but regardless of whether they were friends or lovers, they weren’t afraid to be different, and this enabled them to embrace the life they desired – a life of happiness and quiet contentment, and to a degree, a life of celebrity.

Plas Newydd is more than just bricks and mortar: it is a place that symbolises the possibility of change, and is a reminder to us all, over 200 years later, that we must continue to strive towards a society of acceptance.

‘My expectations were more than realized & it excited in me, for a variety of circumstances, a sort of peculiar interest tinged with melancholy. I could have mused for hours, dreamt dreams of happiness, conjured up many a vision of … hope.’

Anne Lister (The Secret Diaries of Miss Anna Lister, edited by Helena Whitbread)

With thanks to the tour guides at Plas Newydd who helped inform the content of this blog.

What a wonderful bit of history. The term you use, acceptance, is most appropriate. I’ve said to many that our constitution, by granting us freedom of speech / expression, affords everyone the right to express themselves as they see fit. Accordingly, whether we believe an LGBTQ life is correct or not, we are obliged to accept whatever expression those around us might choose.

What we may believe personally or spiritually is never questioned, because it is relevant only to each individual. What another may choose to believe or how they might present themselves, whether it be straight, L, G, B, T, or Q, is entirely their own choice pursuant to the rights our constitution has given us.

So, acceptance is the perfect word. We should & must accept all who present themselves differently than we choose to present ourselves. Bravo to these women who had the tenacity and courage to present themselves as they saw fit.

I enjoyed reading this very interesting article, well researched and presented.

Your blog doesn’t mention Elizabeth Mavor as far as I can see. Her 1971 book ‘The Ladies of Llangollen’ is probably her best known and the one that brought this story to public notice. But she wrote six other non-fiction books and five novels, one of which was shortlisted for the 1973 Booker Prize.

Thanks, Hannah – I visited Plas Newydd last summer, as I’d read about the ladies online and in the journals of Anne Rushout-Bowles and her uncle, George Bowles (who very much admired their library!). The house is wonderful and I hope people will be encouraged to visit it – and perhaps a television programme or film might be made of them, perhaps with Suranne Jones of Gentleman Jack as one of the leads.

Love it . Have visited Plas Newydd as used to live in Wrexham and always took visitors to lovely Llangollen . Lost count of the times we visited the town, rode on the railway , walked across the Chain bridge and climbed up Dinas Bran . Magical memories to treasure

How wonderful to find this article just as we are planning a visit to Llangollen later this year. Having passed through the town many times on the way to visit relatives as a child, I had read the story many years ago but never had the opportunity to visit the house. Here’s hoping it will be open when we are staying there later in the summer!

A very moving story and what a different world they lived in. I have never visited, although my wife and I spent many happy weekends in Llangollen many years ago.

We must go again this year.

What a lovely true story.

I hope to visit someday.

Thank you for sharing.

Louise

There’s a long, detailed and appreciative description of a friendly visit which Prince Puckler Muskau made to the Ladies of Llangollen in July 1828. Amongst much else, he mentioned his “lively sympathy for the uninterupted, natural and affectionate attention with which the younger treated her somewhat infirmer friend.” This was printed in the Prince’s anonymously published account of his Tour in 1833 (pp. 317-9) Michael Leach

V ery sympathetic and comprehensive. A model for this day and age,to encourage people to share their lives sexually or not, whatever people think.

Lovely story of the two ladies who made a lifestyle for themselves. I doubt that they ever had to do things that they never wanted. They lived the life they wanted and it seems they were happy. Well done Eleanor and Sarah.

Oh I am so thrilled to be reading about these remarkable women right here on the National Archives site. What an excellent read! Through my mother, I am a very distant relative of the Earls/Dukes of Ormond (my mother is a Butler from Kilkenny) and the book The Ladies of Llangollen by Elizabeth Mavor sat on our family bookshelf for years. I finally read it as a young teen, just as I was beginning to fully comprehend the meaning of my own (paternal) aunt’s lifelong friendship and relationship with her beloved wife. My own aunt came of age in Nazi Germany and for her to stay true to her authentic self, while growing up in the shadow of an uncompromising regime, was something I’ve always greatly admired.

The classic work on their lives is Elizabeth Mavor’s “The Ladies of Llangollen”. It’s thanks to Mavor that I first heard of the novel which had inspired them, and its author Sarah Scott. “Millennium Hall”, published in 1762, featured a utopian community of women-loving-women, based on an idealised version of Scott’s own life with her beloved Lady Barbara Montagu, with whom she had run away.

I also enjoyed this story. Thankyou for placing it on your blog. I have only just seen it and was also very interested to read the comment by Deirdre Wolf about her Butler ancestry.

I am also descended from the Butlers of Kilkenny, in this case my great great grandmother Bridget Butler of Kilfane. Her daughter migrated to South Australia in 1859.

I have placed information on the free Ireland XO page.

A delightful read, so many memories of our visit to the beautiful town of Langollen and Plas Newydd while cruising the Llangollen Canal. Such ingenious women with determination who created a home.

A really interesting article. You have inspired me to visit Plas Newydd 🙂

This blog has really brought the story of these two incredibly brave women to life! An interesting balance of first hand experience from your trip, with artefacts from the collection and a well researched narrative, thank you. I hope there are funds available to allow for a research trip to Shibden Hall!

I spent a lot of years of being so intrigued and so curious about The Two Ladies. Wanting to live their lives as they wanted, took a lot of courage and sheer determination. As myself mid way in life, probably at the same age that Lady Elenor was when she and Sarah decided to leave Ireland for England and then Wales, was so endearing to me to discover more of their lives. Also how can one forget the formidable Anne Lister, she knew her heart. These inspirational women made such a huge impact on my life, back then and still does to this day.