Content note: This blog post quotes historic documents that use the term ‘alien’ to describe any foreign national living in Britain, which may be considered offensive. Original legal terms are preserved here to accurately represent our records and to help us fully understand the past.

On 5 August 1914, only a day after Britain declared war on Germany, the 1914 Aliens Restriction Act was passed and non-British citizens were required to register at their local police station.

The primary aim of the 1914 Act was to target ‘enemy aliens’ resident in Britain during the First World War. Five years later, the Aliens Restriction Act 1919 continued the restrictions placed on foreign nationals into peace time. The 1920 Aliens Order extended the powers of the authorities further. Passports were now obligatory and those entering Britain were also required to have a medical inspection. [1]

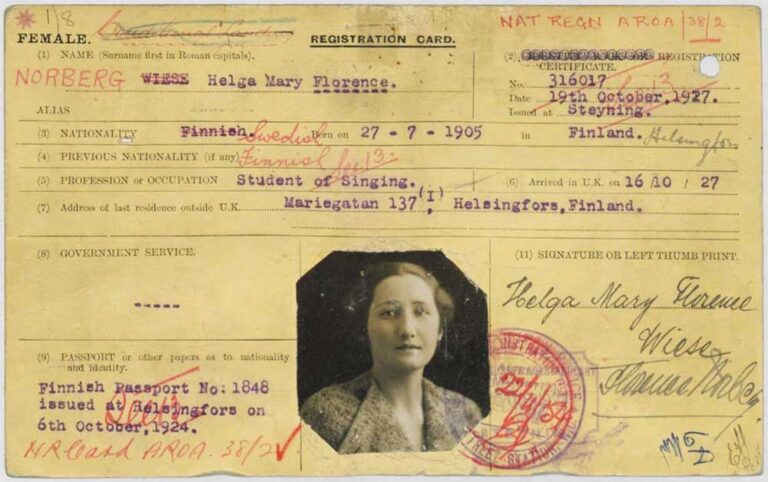

Upon registering, individuals were issued with an alien registration card. The Metropolitan Police series MEPO 35 holds the registration cards for 1,257 people from the London area. They were largely European and migrated to Britain between 1918 and 1957. As the card often included a photograph of the individual, these records are fascinating visual sources for researchers.

This blog post focuses on three people who migrated to Britain during the 1920s. We can trace their stories through their alien registration cards and other records held at The National Archives.

It must be acknowledged that these records only exist because the movements of foreign nationals were policed, and they are largely written from a government perspective. Moreover, the voices of these individuals speaking about their reception, experiences, and the challenges they faced are rarely found in our records.

Helga Mary Florence Norberg

Helga Mary Florence Norberg arrived in Britain in 1927 and was of Swedish nationality. She had previously held Finnish nationality and had resided in Helsingfors, Finland. Her occupation is recorded on her registration card as ‘Student of Singing’ and she lived in various places in Sussex and London.

A later entry in 1932 noted that there was ‘No objection to alien prolonging her stay for purpose of study’. A year later, Norberg applied for naturalisation (the legal process of changing one’s nationality) to attain British citizenship, but this was rejected.

The 1939 Register listed Norberg living in St Marylebone, London, with her husband Eric Norberg. Her occupation was listed as ‘music hall artiste on own’, and her husband’s occupation as ‘Medical Instructor’.

For a short period between 11 August 1941 and 7 September 1941, Norberg was excepted from the Aliens (Movement Restriction) Order, 1940, ‘as the Holder is actually engaged on a tour organised by E.N.S.A. [Entertainments National Service Association]’, an organisation which provided entertainment to those serving in the British armed forces during the Second World War. It is likely that she worked as a singer. Subsequent entries for 1942 and 1943 show that she continued to be employed by E.N.S.A.

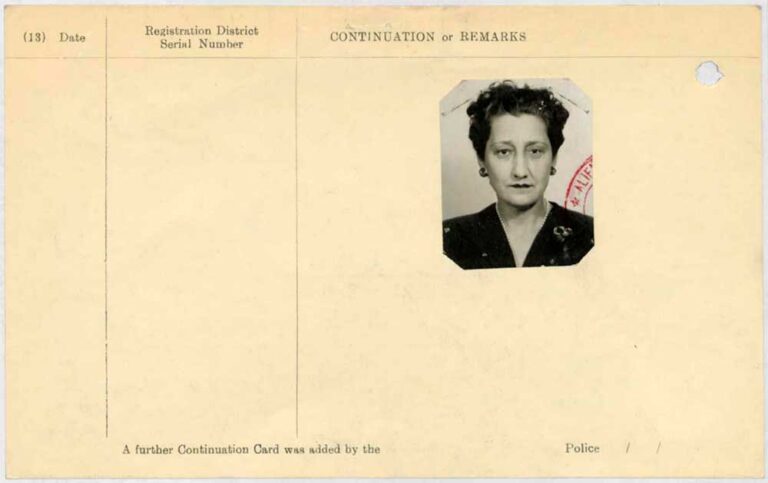

On the penultimate page of Norberg’s continuation cards, there is another photograph of her taken in the early 1950s. This is a particularly rich record, as it is rare to have two photographs taken at the beginning and end of the cards.

Surprisingly, Norberg’s continuation cards were not stamped to say that she had been naturalised, which may have been an administration error. Nonetheless, The National Archives holds Norberg’s certificate of naturalisation, which was issued on 28 March 1963.

The certificate stated that Norberg had met the conditions for naturalisation under the 1948 British Nationality Act, and that after taking the Oath of Alliance she would become a citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies. It also recorded that she was employed as a ‘Teacher of Singing’ and by this point was widowed.

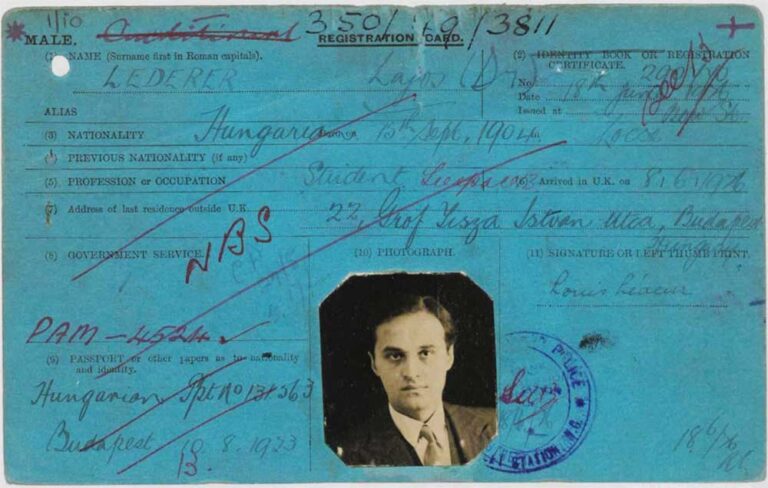

Lajos Lederer

When he arrived in Britain in 1926, Lajos Lederer was also recorded on his registration card as being a student. A Hungarian national, he came to London when he was 21 to study a PhD in law.

A later continuation card notes that Lederer’s title had changed to ‘Dr’, suggesting that he had completed his PhD. He subsequently became a journalist and worked for the Daily Mail, before being appointed London correspondent for the Pesti Hirlap, the largest Hungarian daily newspaper. [2]

On 20 June 1940, Lederer married Jean Windemer, who was a British citizen (although upon marriage she acquired her husband’s nationality). Just over a year later, an entry on his card for 7 December 1941 stated that he was ‘INTERNED by order of the Secretary of State’.

During the First and Second World Wars, Britain established internment camps to hold ‘enemy aliens’ – individuals residing in the country who were believed to be a potential threat. Lederer was interned in a camp on the Isle of Man. Although he had Jewish heritage, his internment was likely due to his Hungarian nationality – Hungary was a member of the Axis powers – and his profession as a journalist. [3]

The Home Office created personal files for some foreign nationals who applied for naturalisation, which can be found in HO 405. Several influential figures campaigned for Lederer’s release, and in his Home Office file there are numerous letters concerning his internment.

Lederer’s wife Jean wrote to the MP Nancy Astor on 13 January 1942, asking if there was anything she could do to help given Astor was an ‘old friend’ of her husband’s.

‘It is because I feel his internment is wholly unjustified, and because I know so well how much he loves England and loathes the Nazis, that I am doing all I can to get his release.’

Jean Lederer, 13 January 1942

On 2 March 1942, Lederer himself wrote to the MP Randolph Churchill and thanked him ‘for the magnanimous support you gave for my case.’ He went on to state ‘My Pro-British and anti-Nazi sentiments were testified by more than a dozen reliable and prominent men, what then are they suspicions against me?’

This letter also provides an insight into Lederer’s personal experience of the internment camp and his mental health, living ‘behind the barbed wire’:

‘The loss of liberty – for no earthly reason – is apt to create in you most poisonous visions. I even were wondering at times if my friends who knew me well will continue to stand by me’

Lajos Lederer, 2 March 1942

Lederer’s connections with the British elite, such as the Astors and Randolph Churchill, likely helped to secure his release, which occurred on 16 March 1942 and is recorded in his Internees Index Card. He successfully applied for naturalisation in 1949 and continued to work in journalism.

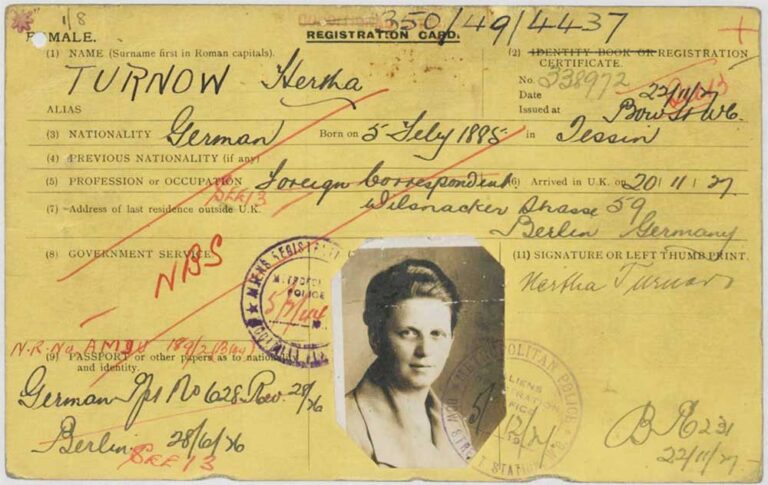

Hertha Turnow

Hertha Turnow arrived in Britain in 1927 and was of German nationality. Her occupation was recorded on her registration card as ‘Foreign Correspondent’ and she was first recorded as living in Kensington, London.

An entry on Turnow’s card for 19 May 1930 reports that her occupation had changed to ‘Housekeeper’, and later entries record her occupation as ‘Cook’.

Turnow’s card records that she applied for naturalisation in 1938, but her application was refused. At this point, Germany’s foreign policy was becoming increasingly aggressive and war was on the horizon. This likely influenced Turnow’s decision to apply for naturalisation, as well as the Home Office’s decision to refuse her application.

The Home Office also created a personal file for Turnow which reveals more information. It records that she had previously worked in Berlin as a clerk for Schenkers and travelled to Britain ‘to take up a temporary job in the London office of Schenkers…a well-known shipping and forwarding agents’ firm’. Indeed, they questioned why a woman would take ‘up domestic work after so long a career in business as a very intelligent foreign correspondent clerk’.

A report produced by the Metropolitan Police shows that Turnow worked in various domestic service roles but also experienced spells of unemployment. She ended up leaving these roles ‘because of prejudice against people of her race…and was maintained by friends’, demonstrating the discrimination she experienced.

Turnow was initially exempt from internment, but her Internees Index Card shows she was later interned on 31 July 1940, despite a lack of concrete evidence. With panic growing over the progress of the war, the early 1940s saw an increase of resident non-British nationals being interned.

In 1940, Turnow had taken an English course at the City of London College which was reported by a Mr Ramsbotham as being suspicious. The Metropolitan Police subsequently reported that:

‘In view of the fact that she is a domestic, and at the age of 55 is taking a course at a business college, the suspicion of Mr Ramsbotham may be well founded. There is also the fact that she has four blood relations – who she visited in 1937 – living in Nazi Germany.’

Metropolitan Police, 23 July 1940. Catalogue reference: HO 405/54769

These relations were her three sisters and brother.

However, Turnow was released from internment on 20 July 1943. Her penultimate continuation card states that she applied for naturalisation on 24 September 1949, which was successful. Her occupation is listed on her naturalisation certificate as ‘Shorthand Typist’.

The stories of Helga Norberg, Lajos Lederer, and Hertha Turnow provide us with an insight into the lives of those who migrated to Britain in the early 20th century, and the impact that legislation and war had on them personally.

Although limited in number, the aliens’ registration cards that do survive provide a wealth of information on foreign nationals who made Britain their home.

The alien registration cards in MEPO 35 have been digitised and can be accessed via our catalogue Discovery. However, for reasons of data protection, only 976 can be downloaded because their subjects were born before 1922. Newly digitised records are added annually. You can find out more information in our research guide, aliens’ registration cards 1918-1957.

There are also some regional collections, such as the Alien registers from Salford City Police.

Footnotes

[1] Becky Taylor, ‘Immigration, Statecraft and Public Health: The 1920 Aliens Order, Medical Examinations and the Limitations of the State in England’, Social History of Medicine, 29 (2016), pp. 512-533.

[2] Note on Mr. Lajos Lederer attached to a letter from Anthony Zsilinzky of the Association of Hungarians in Great Britain to R.M. Makins of the Foreign Office, 29 December 1941, FO 371/32624, The National Archives.

[3] Donald Trelford, Shouting in the Street: Adventures and Misadventures of a Fleet Street Survivor (London, 2017).