Our Research Exchange series features interviews with researchers across The National Archives in which they discuss their new discoveries and their work’s potential for impact. The purpose of the series is to highlight and demystify the research we do and open up new ideas and discussion.

This month, to coincide with our Annual Digital Lecture, we have three blogs focused on themes related to our digital research: Preservation, Presentation and Interpretation.

This blog focuses on the theme of Presentation, discussing how we work with digital platforms and technologies to display our records in interesting and practical ways. We have invited some of our researchers to speak about the following projects:

Jenifer Klepfer on Project Etna

Digital Services has been working on Project Etna (‘Explore the nation’s archives’), a project to develop our website and online catalogue to be more inclusive, disruptive and entrepreneurial in line with The National Archives’ strategic vision. This includes breaking down the silos between the evidential and contextual data we hold (e.g. the catalogue and our interpretive content about the catalogue) and also looking to design the interface and experience to present these different facets of the collection in a more cohesive way.

We are also looking at how we can make our website and online catalogue easier to use and more welcoming for users with little or no archival experience, or those who do not feel confident using digital tools and services.

Dr Katherine Howells and Sarah Castagnetti on COI75

The Central Office of Information (COI) made thousands of films for the government. The best remembered are probably the public information films from the 1960s and 70s, but there was much more to the COI than that. It also made many films that are unfamiliar to the British public and indeed were never meant to be seen by them, and together the COI’s output offers an insight into life in Britain in the second half of the 20th century.

To mark the 75th anniversary of the creation of the COI, we joined forces with the British Film Institute (BFI) and the Imperial War Museums (IWM) to look at the films and documents held by each organisation, and to highlight the stories they revealed.

Dr Lora Angelova and Bernard Ogden on Deep Discoveries

Lora and Bernard have been working with partners including the University of Surrey, the Victoria & Albert Museum and the University of Northumbria to explore visual search across different collections. The project used artificial intelligence to find images based on other example images, rather than looking for words in descriptions. We also did a lot of research to understand how to build a suitable user interface.

What motivated you to begin this research?

[JK]: Through previous user research, as well as through feedback from across the organisation, Digital Services are aware of the challenges that new and less confident users face when using our catalogue and website. This project started with a reimagining of what our digital presence might be.

What if we could link data in a way that overcame current constraints between the evidential (the records in our catalogue) and the contextual (the rich resources about our collection such as blogs, research guides etc.)? What if we could provide a search experience that users with no archival experience might be able to master? What if we could present our collection in a way that captures new users’ imagination and draws them into the collection?

As part of our public task we work to ensure access to our records and our goal is to try to make that experience as inclusive and as easy as possible – a big challenge, especially when the data we hold is, in many cases, poorly described or disjointed. The importance of this work became even more apparent during recent lockdowns when the only way to access our catalogue was via the internet.

[KH and SC]: The Central Office of Information (COI) produced films between 1941 and 2011 covering a huge range of subjects that reflected the issues of the day – from road safety and food hygiene to AIDS awareness and what to do in the event of a nuclear strike. Many of these films have been preserved by the British Film Institute and the Imperial War Museums and a lot of them can be watched online free of charge.

The National Archives has over 2,500 files about the making and commissioning of these films, which add to our understanding of the issues the government was trying to address through them. With the 75th anniversary of the creation of the COI in April 2021 it seemed like an ideal opportunity to bring the BFI, IWM and The National Archives collections together to highlight and celebrate the COI’s work.

[LA]: At The National Archives we have a very large, but little-known design collection. The designs are housed in large and cumbersome volumes, and they are not digitised, nor are they described (visually) in our catalogue. Having had a few artists and designers look at them in the conservation studio, we had a recurring question: ‘How can I find more designs that look like this one?’ So the idea to explore visual search for heritage collections seemed like a natural way to address this problem.

[BO]: It has the potential to let you find what you are looking for without needing to know how to put that into words. It can work even if the images are not described at all. Building an interface to search without words is an interesting challenge.

What surprising discoveries have you made?

[JK]: One really big surprise is how quickly user research practices developed to be fully remote, and how well participants adapted to this. During the alpha phase of this project, we wanted to conduct research with people from across the UK. We found that the team and participants struggled with video calls and other remote tools for user research. Once we all had to work from home however, the upskilling was incredible. Participants are now well-versed in tools such as Zoom/Teams/GoogleMeet, and are adept at screen sharing etc.

Within a matter of weeks, it seemed almost like users with low digital confidence had disappeared. We now have to work very hard to find participants for sessions with users who struggle with digital tools

For the private beta of this project we invited a large number of users to take part and we segmented them by characteristics: users who had experience of The National Archives and those who did not, users who were confident with digital tools and those who were not. One surprising learning from this (we are in the early stages of analysing the results of the private beta so this needs to be taken with a pinch of salt) is that it seems that it is users’ experience of archives rather than of digital tools that has the most impact on their experience of our digital services.

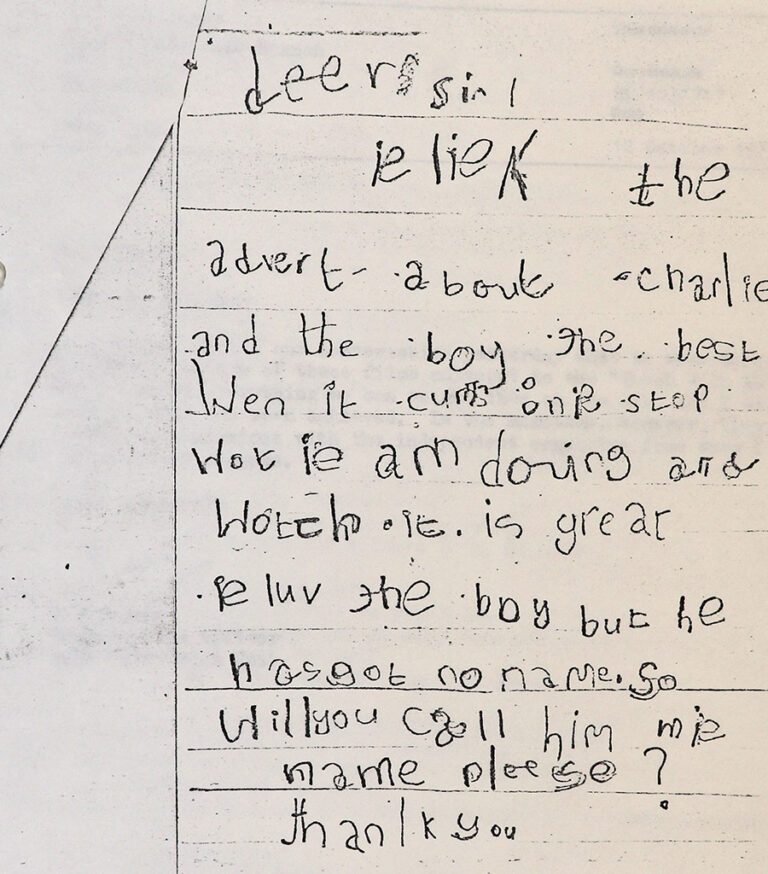

[KH and SC]: We’ve looked at dozens of production files for films produced by the COI and have learned a lot about how the films were initially conceived, the research that went into them and occasionally how they were received by viewers.

In one file we found a letter from a four-year-old boy called Russell in Liverpool, who wrote to the Home Office about the short safety films aimed at pre-school children, featuring Charley the Cat. Russell liked the films so much that he asked if the young boy in the films could be named after him.

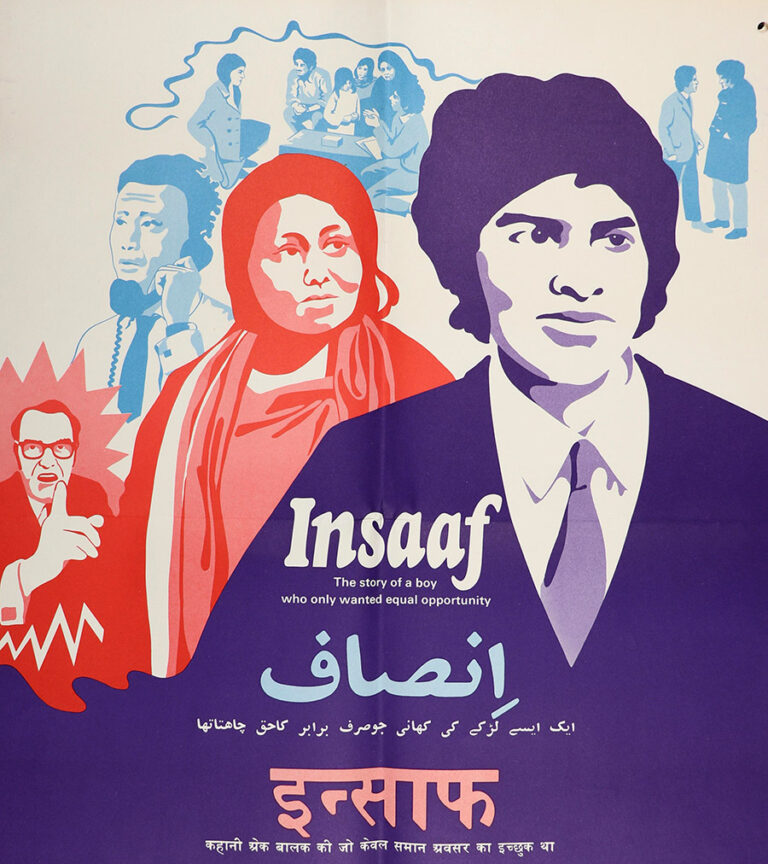

We’ve also watched films from the 1960s and 70s that were trying to raise awareness of Race Relations legislation. The film ‘Insaaf’, which means ‘justice’ or ‘fair play’ in Urdu, was made in 1971 and was filmed partly in Urdu. It features a young South Asian man and his family dealing with discrimination following a job interview. Watching the film with colleagues prompted some fascinating discussions about the way the family and South Asian culture was represented.

[LA]: The project led us to explore the theme of ‘explainable AI’, which allows users to see and understand how computer vision search algorithms work, as they are making use of them. It is a very exciting development, but we discovered that it can be tricky to make that experience both seamless and visible to the users.

[BO]: Exploring our prototype was quite interesting. I found that sometimes I could tell myself stories about why the images that come back are similar and this would lead me to see the images from a different point of view. In this way, it might not matter if I’m right or wrong about why the AI thinks that the images are similar – either way, I’m getting some value from the search. Being aware of this idea in the abstract is quite different from experiencing it.

What makes this project important – for The National Archives and beyond?

[JK]: It is our hope that our work on Project Etna will make The National Archives much more inclusive of new users and continue to serve, and possibly delight, the more experienced users. We hope that the collection will be more accessible to more people – especially in an era when facts are so important.

The National Archives collection is fascinating and has so many incredible artefacts. We really hope our work connects more people with the records they are looking for but also encourages more people to discover some of the unexpected gems. We hope to bring the archive online to a wider and more diverse audience.

[KH and SC]: The project has created and developed relationships between film curators at the IWM and BFI and record specialists at The National Archives. This has presented opportunities to highlight our collections to each other’s audiences and to understand more about these collections ourselves. These relationships have already proved fruitful outside the COI75 project as well as within it.

Films are an easily accessible medium that can reach audiences that haven’t previously engaged with archives at all. In turn, their observations on and responses to the films can add valuable new perspectives and help us to see beyond the obvious. For example, films aimed at viewers in former British colonies, or at minority populations in the UK, have great potential to facilitate engagement with under-represented communities and for us to learn more about the impact and understanding of the films then and now.

[LA and BO]: As part of the AHRC’s ‘Towards a National Collection’ programme, ‘Deep Discoveries’ was one of a set of research initiatives focused on the needs of GLAM organisations as they navigate the complexity (and exciting possibilities!) of making their collections digitally available to audiences around the world. The ability of our online visitors to visually search, discover and connect images across the UK’s collections was a primary motivation for our team.

[BO]: The project also speaks to important questions in interface design and in artificial intelligence. It has given us a vehicle to think about how we design interfaces that are useful for different kinds of people, about who the audiences are for cultural heritage, and about how our sector can reach audiences that are left out today. It also helps us to reflect on how best to help users to interact with artificial intelligences, which are likely to be a growing part of how we access collections digitally.

What has been the biggest challenge of this project and what were the solutions?

[JK]: The biggest challenge has been recruiting users who have not used The National Archives to take part in user research. It is hard to reach audiences who are not already engaged with us! We reached out across our own personal and professional networks and in collaboration with The National Archives’ Marketing department to connect with people who have not used or even heard of us.

Another challenge was balancing the constraints of archival practice and the principles of effective design as we reimagined pages such as Collections Details. We also had a challenge balancing the desire to create engaging, innovative and at times very visual digital experiences, such as interactive timelines and generous interfaces, with our desire, and legal responsibility, to create a digital service that is accessible to all. These constraints are actually opportunities to be creative and we had to apply ourselves as we approached this.

[KH and SC]: This project began during lockdown, which made progress more difficult in some ways. At first, access to original records and films was limited. This meant the project team had to work together to provide digital access to one another through, for example, photographing production files during the limited periods we had access to them.

Virtual meetings, necessitated by lockdown, have facilitated collaboration as we have been able to meet more regularly and be more agile in our collaboration than might have been possible pre-pandemic.

These difficulties have also encouraged us to take advantage of digital means of public engagement; the project was launched with a collaborative film, with contributions from members of the team filmed at home, hosted by the BFI as part of their ‘At Home’ series.

[BO]: A key challenge was to build a prototype interface that could speak to both the user interface design and the artificial intelligence research goals of the project. The interface had to be engaging and useful but it also needed to include the AI’s explanations of similarity. Users need to be able to tell the AI the aspects of the image they are interested in (i.e. colours, shapes, objects) and also need to understand what the AI “thinks” is similar about the images that it finds.

The team at the University of Northumbria produced a series of prototypes which gave us all something concrete to focus our discussions around. This let us create an interface that allowed all of the research to move forward.

How will the digital methods used remain up to date over time?

[JK]: One of the things I love about working in the field of digital user experience is that we are always learning. Things keep changing and we must acquire new skills and continuously improve our work, but the foundations of user-centred design and problem solving do remain the same, even if some of our methods evolve.

We have tried to ground our work in sound design principles and hopefully have avoided being too ‘gimmicky’ in our innovation for this project, so it will stand the test of time longer than it might have done. The work behind the scenes to join up data sources, and also the recent migration of our digital services to the cloud, puts us in good stead for the future and is a solid foundation to build and innovate upon – but who knows what the future holds?!

[KH and SC]: The digitally facilitated collaboration essential to this project provides a model for future projects working with other related institutions. The project has demonstrated effectively that public engagement materials can be produced remotely and collaboratively, drawing on records from multiple institutions, to present ongoing research and inform and entertain.

[BO]: We came up with several ideas for user interfaces and we learned a lot while we were creating and testing the one idea that we pursued. Although this project has ended, it would be really interesting to try out some more ideas that build on what we have learned. As the project is a part of the ‘Towards a National Collection’ programme, its insights will hopefully feed into future TaNC projects.

Where can we learn more about the project?

[JK]: You can find out more about Project Etna (and its forerunner Project Alpha) following the links below:

More about Project Etna: blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/introducing-project-etna/

Our blog on Medium: medium.com/the-national-archives-digital

Three blogs written at the start of this project:

[KH and SC]: The National Archives, IWM and BFI collaborated on a blog and a film to launch the project. You can see The National Archives’ blog on our website and watch the film on the BFI’s YouTube channel. On Twitter, search for the hashtag #COI75 to find social media posts from all three organisations.

[LA]: You can visit our webpage,and watch a number of webinars about our project’s methods and findings on the AHRC’s Towards a National Collection YouTube channel. You can also read the final report on the AHRC’s Towards a National Collection website. From August 2021 to January 2022 you can play with the prototype online.

To learn more about our research at The National Archives, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/about/our-research-and-academic-collaboration/.