Our Research Exchange series features interviews with researchers across The National Archives in which they discuss their new discoveries and their work’s potential for impact. The purpose of the series is to highlight and demystify the research we do and open up new ideas and discussion.

This month, to coincide with our Annual Digital Lecture, we have three blogs focused on themes related to our digital research: Preservation, Presentation and Interpretation.

This first blog focuses on the theme of Interpretation – how do we use digital methods to explore our collection and catalogue in new ways? We have invited some of our researchers to speak about the following projects:

Andrea Kocsis on Operation War Diary

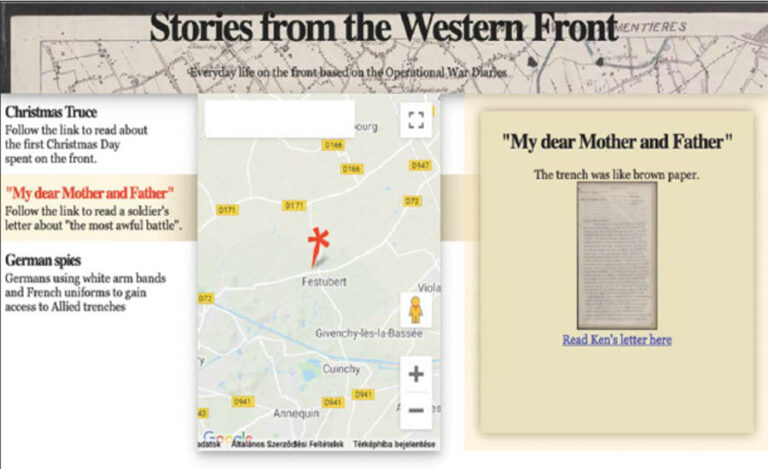

The Operation War Diary (OWD) was a 5-year-long collaboration between Zooniverse, the Imperial War Museums and The National Archives. It involved thousands of volunteers who digitally annotated more than 900,000 documents from the WWI Unit War Diaries, the daily reports from the trenches. My first task was to organise these annotations to help make them available for wider audiences. My second task was to find ways to visualise this information in a more interactive way and facilitate the interpretation of this large amount of unorganised data.

Dr Neil Johnston on Beyond 2022

Beyond 2022 is an all-island of Ireland and international collaborative research programme to recreate digitally the Public Records Office of Ireland (PROI) as it was in 1922. Several of the most important memory institutions worldwide have joined in the shared mission to reconstruct Ireland’s lost history.

Comprising five Core Archival Partners (National Archives of Ireland, The National Archives UK, Public Records Office of Northern Ireland, Irish Manuscripts Commission, Trinity College Dublin Library), and over 50 other participating institutions across the island of Ireland, Britain, the USA and beyond, the project is working to recover what was lost in that terrible fire 100 years ago.

On the centenary of the Four Courts blaze, the Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland will be launched online. Many millions of words from destroyed documents will be recovered, digitally linked and reassembled from copies, transcripts and other records scattered among the collections of the assembled archival partners.

Dr Jo Pugh on catalogue research

Digital methods give us a way to ‘zoom out’ and get an overview of lots of data. My collaborator, Dr Richard Dunley, and I were interested in seeing what the shape of large portions of The National Archives’ data in Discovery could tell us about how the archive works, and what the effect of this was on historians’ research behaviours – to what extent does the catalogue ‘make history’.

What motivated you to begin this research?

[AK]: This research is all about experimenting. I had free hands and a blank canvas to create something valuable – not only for historians but also for anyone interested in people’s lives on the fronts during the First World War. This freedom is a rare opportunity in research. It is also a very versatile project: it involves history, archiving theory, data science, GIS and a lot of visualisations – I could never become bored during the project.

[NJ]: Next year marks the centenary of the destruction of the Four Courts in Dublin, where the collection was housed. Back in 2016, Dr Peter Crooks and Dr Seamus Lawless (†2019) began a scoping project to assess whether the collection could be put back together digitally and they approached myself and Paul Dryburgh (Principal Medieval Records Specialist at The National Archives). We’ve been part of the project ever since.

During the scoping phase it became clear that the necessary collections, technology and expertise could be assembled to pursue a full-scale reconstruction of the PROI. Since then, we’ve increased our involvement in the project as it scaled up and are now in Phase II (Discovery), which is hosted by the ADAPT Centre at Trinity College, Dublin, where the academic and archival research is supported by Principal Investigators from the School of Computer Science and Statistics with expertise in virtual reality, semantic web, linked open data, and information retrieval.

This partnership reflects the broader collaborative ethos of the project, where historians, conservators and archivists work hand-in-hand with computer scientists and data experts. Together they have designed a bespoke architecture that has enabled Beyond 2022 to build a digital infrastructure that allows the seamless ingestion of data (metadata, images, transcriptions) that repopulate the virtual Record Treasury.

[JP]: I started looking at the variation in cataloguing within large departments held at Kew – the Chancery, the Foreign Office and others. I’d also done some earlier work looking at things like which series from the collection were most-cited on Wikipedia, or showed up in citations in certain journals.

I’m often thinking about how to create overviews of archive collections because we hold so much material and we’re actually quite bad at showing simply and clearly ‘what we hold’ – a database front-end isn’t generally the clearest way of answering that question. We also know that archive catalogues have wide disparities between the best and worst described collections but keyword search can make it look like you are searching everything equally. I was looking for a way to visually represent those differences.

What surprising discoveries have you made?

[AK]: Before the project, we weren’t aware of the amount of visual content hidden between the pages of the Unit War Diaries; however, the volunteers, looking through thousands of pages, discovered and annotated sketches and maps hand-drawn by soldiers.

In my view, these unique pages are a special and intimate way of connecting with our past and ancestors through a piece of thin paper. I was so moved by these sketches that I decided to centre one of my visualisations on them. The Maps on Map prototype is all about locating these images on the current map of the Western Front, making the landscape the soldiers saw comparable with what we can see today.

[NJ]: I’m a historian so I’m part of the Archival Discovery team with responsibility for identifying replacement collections in British archives, libraries and repositories. There have been many startling discoveries made as we have rigorously worked through archival collections, but I think the most surprising element of all of this is the volume of materials that act as replacement records. At The National Archives alone we have identified over 200,000 Irish or Irish-related records that will help to digitally repopulate the collection.

[JP]: I think the big surprise for me was realising how huge the disparities between the most completely and least completely described collections actually were. We were also able to demonstrate with data some things that hitherto I think we strongly believed but hadn’t proved: that increased cataloguing has a direct and measurable effect on historians’ viewing of material, that the catalogue changes substantially over time, and that we can actually see the differences between the collections as they exist on the repository shelves (in terms of the space they take up) and how many catalogue descriptions are created for each metre of those collections. Huge, huge differences in some cases. This really affects how historians ‘fish’ for facts and documents, an analogy used by E H Carr in his famous book ‘What is history?’.

What makes this project important – for The National Archives and beyond?

[AK]: The National Archives has been planning to organise and interpret this digital dataset for a while as there is a wide interest in its content. Thanks to the Friends of The National Archives, finally, we have enough funding to dedicate enough time to this project. I expect this way we can give valuable results back to those thousands of volunteers who contributed to the crowdsourcing. In a broader sense, the First World War is part of our family history. Gaining a closer and newer understanding of life on the Fronts is something we can do to respect the memory of our ancestors. I hope my work will help individuals to connect deeper with their past.

[NJ]: Beyond 2022 reflects many of The National Archives’ ambitions. It will primarily provide more access to the Irish collections here, but by semantically linking disparate collections to now destroyed records, we are creating a powerful model for archival reconstruction.

The collaboration between numerous organisations is the key to its ongoing success and our involvement allows The National Archives to showcase many facets of its expertise: archival and collections knowledge; conservation and heritage science techniques; as well as frontier research in the semantic web, transcription and 3D visualisation. It is also the first time that the three National Archives in London, Dublin and Belfast have collaborated on a project of this scale and ambition.

[JP]: I hope that these basic methods will be picked up by others as a way of understanding catalogues more deeply, how they have been shaped by the preoccupations of archivists, and what impact that has on historical methods and written history. Historians are very good at talking about how they interpret documents but they don’t spend a lot of time thinking about how they locate and select documents and how they demonstrate the representativeness of the documents they looked at. Looking at catalogues in this way also improves their transparency and allows us to ask questions about prioritisation of cataloguing and digitisation, which is hugely important for the credibility of cultural organisations.

What has been the biggest challenge of this project and what were the solutions?

[AK]: The biggest challenge is dealing with the uncertainty and fuzziness in the dataset. There were several stages when incorrect information could find its way in the data. The Unit War Diaries themselves could have been noted inaccurately, the annotating and transcribing volunteers could misread something, or information could be lost during the transfer and transformation of the data. Therefore one of my most intimidating tasks is finding the way to handle these errors efficiently. However, I turned this challenge into an exciting opportunity to investigate how digital methods can mitigate uncertainty in crowdsourced projects.

[NJ]: The scale of what we have identified and how to manage multiple workstreams is the major challenge for the project’s leadership team. We are a relatively small group of historians and research software engineers, spread across multiple countries and working with archives from around the world. We have to prioritise how we deal with collections, weighing up what to intensively investigate, which usually involves image capture and transcription, and what to note for future consideration.

The solutions were largely developed by our colleagues at the ADAPT centre, who have built bespoke solutions for us to input metadata, link them to the destroyed collections, and manage how images and their metadata are displayed.

[JP]: We had to come up with a way of measuring and describing these variations. So for example, we talk about ‘mean descriptive density’ – that simply means what’s the average number of words making up a catalogue description for a particular part of the catalogue.

When we were looking at the data from The National Archives’ document ordering system, the sheer size of the dataset we had was a bit challenging but I was able to master just enough SQL to get the answers – the one thing that computers are really good at is counting stuff.

Producing the visualisations was also challenging. It worked insofar as we have something we can show and explain but I definitely haven’t cracked it in terms of what would make plain sense on a webpage. Someone said they looked like static on a telly and they’re not wrong.

How will the digital methods used remain up to date over time?

[AK]: It is inevitable that the digital methods will improve which will open up even more possibilities to make this large dataset interactive, accessible, and further facilitate the research and interpretation of the information it contains.

[NJ]: That’s one of the major challenges we face and something that we spend a considerable amount of time discussing. We have an array of archival experts and historians advising us on best practice, but it’s one of many significant issues that all projects of this nature have to grapple with.

[JP]: I hope they will evolve and develop. The basic tool of The National Archives’ API is there for anyone to use and as more and more catalogues include a pipeline for delivering machine-readable data, it will be easier and easier to apply the sorts of metrics we devised to other catalogues and to make comparisons between them, which would be really exciting. There are much more detailed and sophisticated analyses that could be built from these basic blocks, I have no doubt. I’m really crossing my fingers we will see some.

Where can we learn more about the project?

[AK]: I would advise keeping up with The National Archives’ blog, as soon there will be a post dedicated entirely to the OWD project. A sneak peek is already available in a post by Nicola Hurt, the placement student helping the visualisation of the geographical locations mentioned in the dataset.

[NJ]: Keep an eye on the website, www.beyond2022.ie.

[JP]: Our full article on this work (‘Do Archive Catalogues Make History?: Exploring Interactions between Historians and Archives’) can be found in the Journal of 20th Century British History.

To learn more about our digital research, please visit https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/about/our-research-and-academic-collaboration/.