English-born queens were rare in medieval England. Edward IV and Henry VII had viewed their respective marriages to Englishwomen Elizabeth Woodville and Elizabeth of York as part of the process of ending cycles of civil war, with mixed success. Although Henry VIII’s first marriage to Katherine of Aragon was firmly rooted in the diplomatic traditions of England’s relations with its European allies, his second, to Anne Boleyn, was very much a personal choice, removed from the formalities of international statecraft.

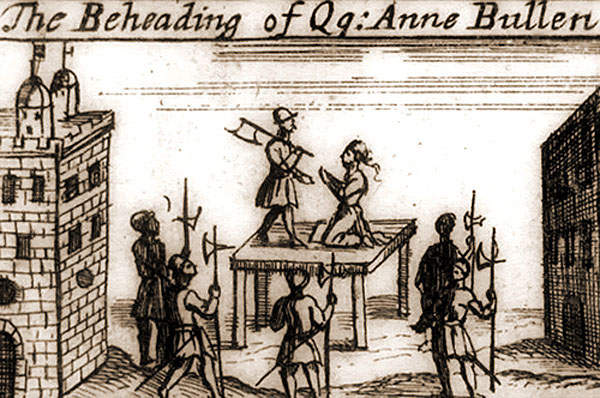

When Queen Anne was convicted of High Treason in May 1536, the nation was deeply shocked. Even if she had polarised opinion as a suitable choice for King Henry, the sentence of death was unprecedented and created political and practical issues that had never previously been faced.

Anne had been condemned to die by a court of peers under the direction of her uncle, Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, at a special trial in the Tower of London on 15 May. With the queen locked in the Tower awaiting the king’s final decision on her fate, the officers of government had to have been ready to do whatever Henry VIII or Thomas Cromwell ordered them to do.

This blog is about some small documents that highlight the big decisions such officials were part of.

Anne Boleyn’s fall from the king’s favour had been rapid. Her miscarriage of a boy in January 1536 probably clouded her personal relationship with Henry and would have been a traumatic experience to recover from. Although this would have been temporary, it reinforced the king’s difficulties in fathering a male heir.

Despite the setback, Henry VIII had continued to press for foreign recognition of his marriage to Anne, even in the weeks before her arrest. He was still interviewing the Spanish Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, in April 1536 in an effort to secure Holy Roman Emperor Charles V’s acceptance of Anne’s status as queen.

For the king’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, Henry’s preoccupation with international acknowledgement of his position as supreme head of the church in England and, more importantly, the validity of his relationship with Anne, threatened to stall royal engagement with wider diplomatic policies. Perhaps this distraction created an opportunity for Anne to assert herself, but it also created the route to her demise.

Historians have shown how Anne voiced her opposition to Cromwell’s plans for the resources grabbed for the king by the dissolution of the smaller monasteries. After agreeing to let her preacher condemn Cromwell from the pulpit of the Chapel Royal in March 1536, Anne seemed to broadcast her intention to intervene in affairs of state and to press her own policy agenda onto the king’s ideas. Despite Anne being Cromwell’s former ally, especially in the area of religious reform, a struggle to influence the king’s thinking put these powerful personalities on a collision course.

It seems likely that Cromwell decided to undermine the king’s confidence in Anne primarily to clear the way for his own power to remain unchallenged, and also to ensure that he could outmanoeuvre and dominate whatever factions formed around the king after her removal. The end to Anne’s influence had to be definitive and permanent if it was also to sweep away her friends in high places and weaken her family and Howard in-laws.

It was unclear at that stage whether Cromwell planned to orchestrate her death or if he simply intended to undermine Anne’s allies and power, as Katherine of Aragon had endured in the early 1530s. A plan soon emerged against the queen that used promiscuousness, adultery and secret disloyalty as its basis – news that was guaranteed to arouse the worst elements of Henry’s characteristics of pride, anger and suspicion. And whatever Cromwell did, he made sure he had the king’s authority to proceed towards ending Anne’s status. No action that touched the king’s dignity so closely could be orchestrated without his agreement.

Cromwell used all his experience of the twists of Tudor power politics to target the informal and playful aspects of Anne’s court. He monitored and interrogated those who were on the periphery of Anne’s circle, such as the musician Mark Smeaton, or others, like Henry Norris, who were familiar with Anne but who moved in and out of high favour.

A case of adultery and incest was assembled. Her brother George Boleyn, and men of the king’s chamber – Francis Weston, William Brereton, Norris, and Smeaton – became her accomplices and, swiftly, co-conspirators against Henry. Naming them as servants of the king’s Privy Chamber, rather than of the queen’s household, only emphasised their personal proximity to Henry in the course of their daily duties – further circumstantial evidence of the danger they presented at the heart of royal private life.

Cromwell hid his machinations from Henry until 1 May 1536. Knowing very well that accusations of the queen’s sexual relations with others at court would trigger his deep worries about the legitimacy of children and his longing for a male heir, it was a short step to turn flirtatious familiarity into a sinister plot to end Henry VIII’s life.

The case was revealed to Henry at the May Day jousts at Greenwich. This very public celebration was quickly halted and the court prepared for a feverish period while the full picture of truth and reality was worked out under Cromwell’s guiding hand.

Once she was tried and convicted, the political turmoil surrounding the queen’s position dominated the royal court. Other officials, however, had to take steps to carry out the sentence. Anne was found guilty of treason rather than adultery, although undermining the king’s dignity was part of the convincing accusation that Anne had turned against her husband.

In 1536, adultery, even by the queen of England, was an offence for the church courts. The law was not changed until after Queen Katherine Howard’s execution, six years later. The 1351 Treason Act required that a woman compassing or imagining the death of the king should be drawn on a hurdle to the appointed place of execution and there burned alive.

Despite the horror of that spectacle, it was nevertheless considered indecent to subject a woman to exactly the same punishment as a traitorous man – drawing, hanging, disembowelment and quartering. Only the king’s intervention could commute this sentence, and while Henry’s will was awaited, preparations had to be made.

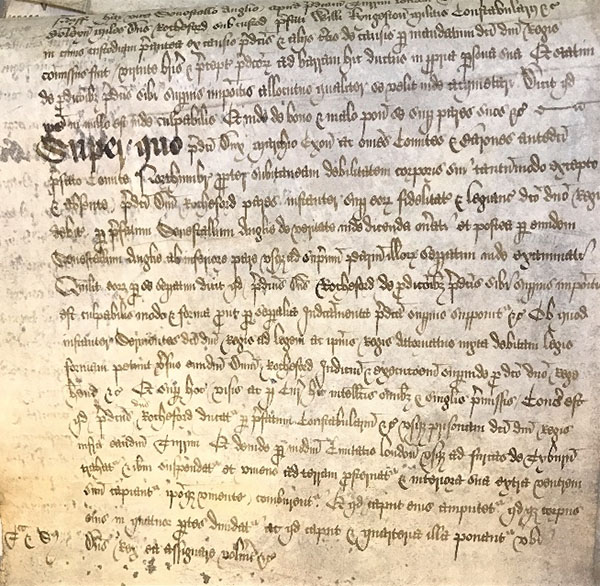

Many questions arose about the detailed procedures of the day of execution, as well as management of the public reaction. Evidence of the comprehensive exchange of orders comes from the record books of the clerks who drew up the writs that carried the instructions which made the wheels of government turn. They also suggest the existence of other contracts, indentures and payments that have not yet been located.

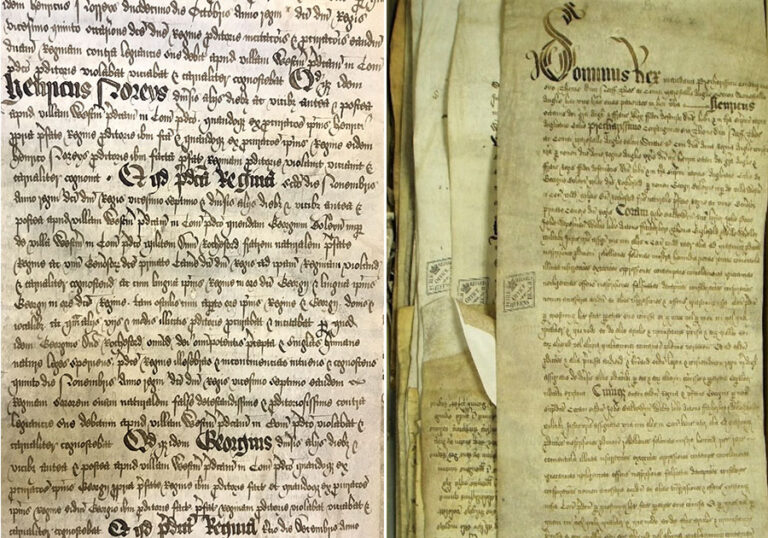

Five Latin writs were copied by the clerk of the crown’s officers in the chancery department (the Crown’s formal secretariat), as a precedent linked to the organisation of the May executions. They are:

- a writ of 17 May to Sir William Kingston to deliver from confinement Rochford, Norris, Brereton, Weston and Smeaton into the custody of the sheriffs of London for execution

- another writ of the same date to the sheriffs of London to carry out their executions by beheading on Tower Hill

- a certiorari writ of 13 May to the trial justices to ensure that they delivered of all of the records of the trials to the duke of Norfolk, who, as earl marshal and steward of England, had presided over the sentencing of his niece

- a writ of 17 May to Kingston to deliver Anne, George and the others to Norfolk’s custody ahead of their executions

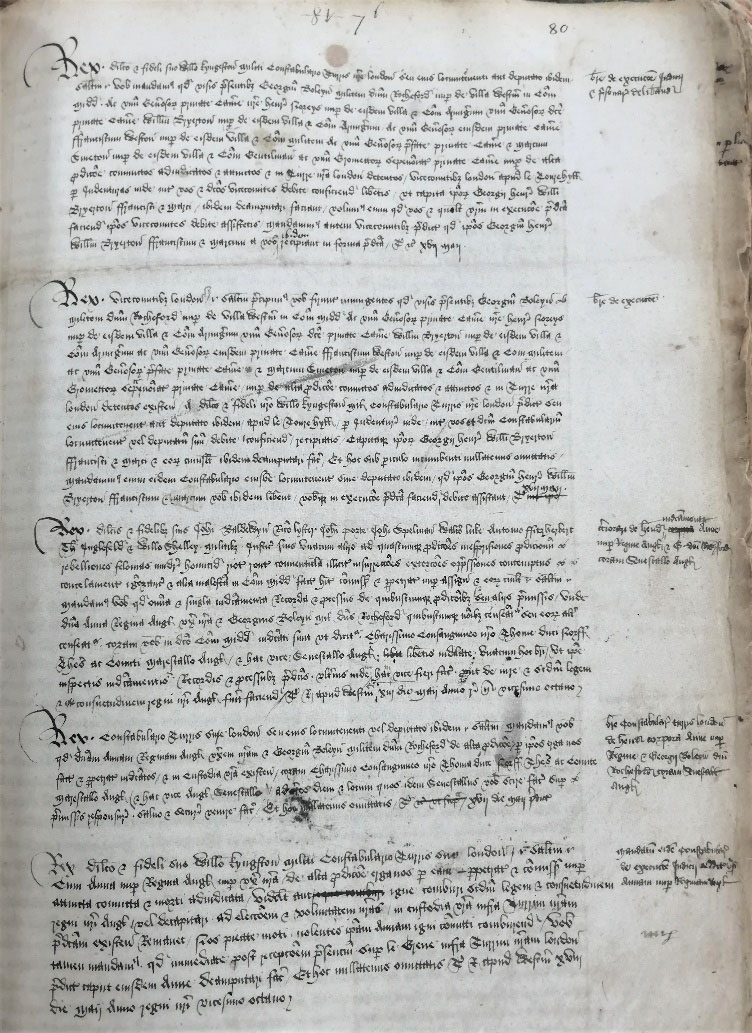

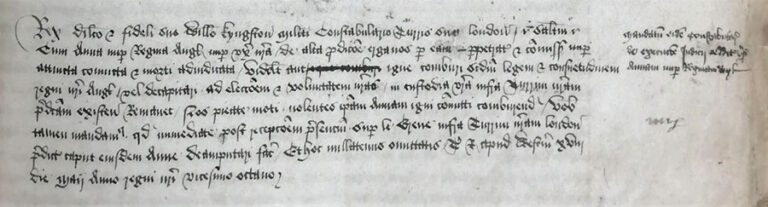

The final writ, of 18 May, relates to the manner and location of Anne’s execution. Although it does not add much to what is known from the reports of Chapuys, or Edward Hall’s contemporary Chronicle, it records the king’s mercy in allowing Anne to be beheaded and not burned. This was effectively the exercise of the king’s prerogative right that was noted in the verdict at the queen’s trial.

The king to his trusty and welbeloved William Kyngston, knight, constable of his Tower of London, greeting.

Whereas Anne late queen of England, lately our wife, recently attainted and convicted of high treason towards us by her committed and done,

and adjudged to death, that is to say by burning of fire according to the statute, law and custom

of our realm of England, or decapitation, at our choice and will, remains in your custody within our Tower

aforesaid. We moved by pity do not wish the same Anne to be committed to be burned by fire. We,

however, command that immediately after receipt of these presents, upon the Green within our Tower of London

aforesaid, the head of the same Anne shall be caused to be cut off. And herein omit nothing [etc]. Witness the king at Westminster xviij

day of May in the twenty-eighth year of our reign.

Reading these procedural writs as a group, there seems to have been some interest in the dimensions of public performance and public opinion linked to the executions. The stipulations of the Treason Act were ignored as both sets of executions were changed to beheadings.

Securing the trial records would attempt to ensure that the scandalous detail of the allegations of incest, adultery and royal impotence would not leak into the public domain. That would have included the papers mentioning the king’s impotency that George Boleyn was not supposed to disclose in court, but read out nevertheless, to Cromwell’s annoyance.

There might also have been worries about how the public executions would be managed and maybe even concerns that officials could be bought off to whisk the prisoners away from confinement. Similar attempts at collusion had happened in the past. References to indentures between the constable and London’s sheriffs for the performance of their duties in respect of these responsibilities might be relevant here.

The organisation of this business in formal Latin writs under the chancery’s Great Seal gave the orders heavy legal weight – more so than letters under the lesser seals or sign manual. This evidence is also recorded in the precedent book from among the thousands of writs in circulation in mid-May 1536.

The unusual nature of what they had to manage meant that the clerks wanted to capture in their own office manuals the specific language and stages of procedure. Any interference, last minute changes of heart or even attempts to grab the prisoners on the way to the block would have been beyond their control, but at least they could demonstrate that they had followed the king’s instructions.

Concerns over security and the outraging of decency were probably at the root of the decision to give Anne a less brutal death. Henry and Cromwell, it seems, had already decided to limit public visibility in efforts to reduce the impact of a queen’s execution. No mention is made in these writs of the Calais swordsman who carried out the beheading. Even the instruction on 18 May for beheading on Tower Green was not followed through as stipulated, since it seems that Anne was killed on a scaffold to the north of the White Tower and, on 19 May, a day later than instructed. Hundreds of people also witnessed her death, as the gates were not closed in time. Clearly, other details remain to be evidenced.

While further records might never be found, following the procedural evidence of the chancery clerks has drawn these writs into the debate. Perhaps the archives still hold more in such collections on the very familiar stories from our history.

Further reading:

Bernard, George W, Anne Boleyn: Fatal Attractions (Yale, London, 2011)

Ives, Eric, The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn (Blackwell, Oxford, 2005)

Warnicke, Retha M, The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn (CUP, Cambridge, 1991)

As for Anne Boleyn being ‘killed on a scaffold to the north of the White Tower’, rather than on Tower Green as mentioned above, Anne was indeed executed on the green (at least by the 16th century definition of what that was).

Back then, Tower Green was a much wider area than it is today, stretching also between the White Tower and the current Waterloo Block. It is now the parade ground.

Today, what is now the green is just between the Chapel of St. Peter Ad Vincula down to the present day Queen’s House.

Also, as the execution was a public event and Kingston expected ‘a reasonable number’, there would have been no reason to shut the Tower gates. The only persons who had been ejected beforehand or denied entry on the day were foreigners, according to Kingston and the Imperial ambassador Eustace Chapuys. The English authorities wanted to control news of Anne’s death (to put their own spin on it) as conveyed overseas.

30/11/20. Last week there were programmes on Anne Boleyn, Chanel 5, and Henry V111 and the Kingsmen on the Smithsonian Chanel (with Tracy Borman).

Fingering historic documents again and again without gloves – in particular the A.B. programme, with the supposed male custodian just flicking through the pages as if they were the Metro! Really??

Like you l cannot understand why such precious documents are handled without gloves.

Thank you for your comments. In a recent blog, a member of our Collection Care department explains our approach to using gloves when handling our collections.

It is standard practice as the fibres from the gloves cause more damage to vellum than oils from skin.

If white gloves cause more damage than the oils from skin, why are some historical documents handled with gloves? I would like to think that hands were freshly washed immediately prior to touching such historically important documents. Would it not be possible to use surgical gloves?