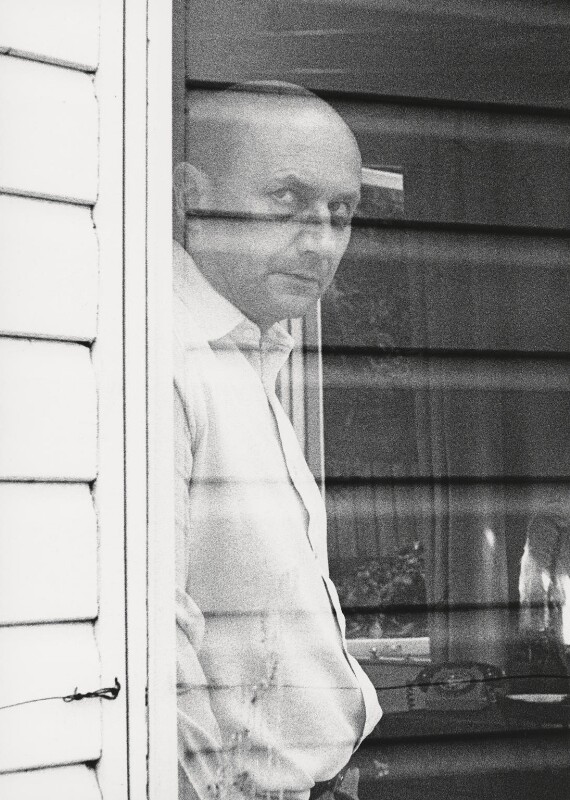

Directly opposite The National Archives, across the River Thames, is a charming white house with bay windows. It was here, in Strand on the Green, where the actor Donald Pleasence lived for many years. Some time ago, walking past, I noticed a Heritage Foundation blue plaque marking it reading ‘Donald Pleasence OBE 1919–1995 ACTOR lived here.’

Pleasence is perhaps best known for his role as Flight Lieutenant Colin Blythe (The forger) in the 1963 iconic film, The Great Escape, a subject featured in our exhibition Great Escapes, closing 21 July 2024. Pleasence, The Great Escape, and The National Archives are seemingly connected. Attempting to tie them together, this blog looks at Pleasence’s personal experiences in the war, the real Blythe (or Blythes), and some of the related documents we hold, which include those about Pleasence himself.

by Godfrey Argent

bromide print, 28 June 1969

NPG x165960

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Pleasence’s military background

The film was based on the book of the same name by Paul Brickhill, published 13 years earlier. The character of Blythe was fictional but like most he was based on real people who were involved in the actual escape on the night of 24/25 March 1944 from Stalag Luft III, in Zagan, Poland.

Pleasence was himself a Prisoner of War (POW) – his story featured in our Great Escapes exhibition – captured at Pas De Calais on 31 August 1944 when serving with 166 Squadron in Bomber Command (1 Group). As a Flying Officer, his plane, Lancaster NE112, was shot down and he was imprisoned at Stalag Luft I near Barth, in Western Pomerania, Germany. He was there from 1 October 1944 until the camp was liberated by the Russians on 1 May 1945.

Like most RAF personnel, before capture he had received lectures on escape and evasion by MI9 British intelligence staff, but, in the end he made no attempt to escape following, on Hitler’s orders, the murder of 50 of the 73 recaptured men from the Great Escape.

After the Great Escape atrocity, in April 1944, British Intelligence did not encourage further escapes.

The map-maker and the forger

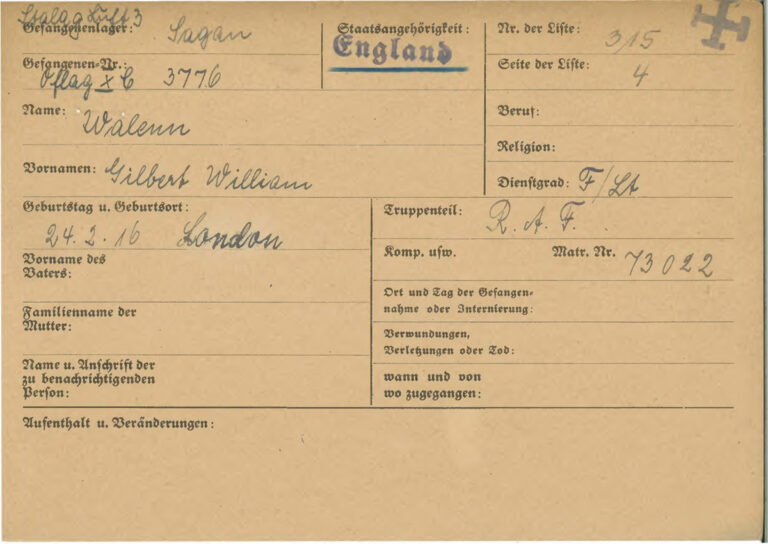

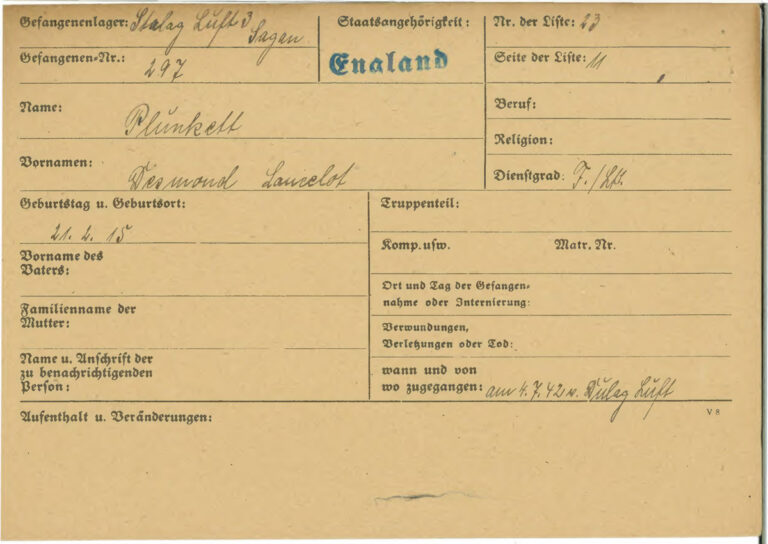

Donald Pleasence’s character in the Great Escape was a combination of Flight Lieutenant Desmond Plunkett, the map-maker, and of Flight Lieutenant Gilbert William ‘Tim’ Walenn who was head of the real forgery operation at Stalag III.

Walenn had been a POW since September 1941, and possessed the ideal skills for that line of work, having been a graphic artist designing wallpaper and fabrics before moving into banking. The forgery department became known as Dean and Dawson after a London travel agency.

Like the character of Blythe in the film, Walenn was one of the 50 who were murdered at six different locations and all of their ashes at now at Poznan Cemetery.

But, there were differences in the character of Blythe and the real Walenn. Physically Blythe was bald whereas Walenn was not and he sported a large ‘handlebar’ moustache. In the film, Blythe went blind but there was no evidence that Walenn had problems with his sight.

20 years after the end of the war, Walenn’s father, Gilbert Walenn received over £1,000 compensation payable under the terms of the Anglo-German Agreement dated 9 June 1964, in respect of National Socialist measures of persecution.

Plunkett’s account

Flight Lieutenant Desmond Plunkett, the map-maker did survive though and his account of the actual escape can be found in WO 208/3336. He was interviewed on 2 June 1945 and his report, MI 9/S/PG/LIB 48, reads:

On 24 March 1944, I escaped through the tunnel known as ‘Harry’ in the North Compound, Stalag Luft III (Sagan). I was the thirteenth man in the tunnel. I was dressed in my own RAF uniform dyed navy blue and altered to look like a civilian suit. I also wore my RAF greatcoat with civilian buttons and the belt buckle covered with leather. I was in possession of forged identity papers, travel permits and letters from firms.

On leaving the exit from the tunnel about 2300 hours, I was joined in the woods by F/Lt Dvorak. My experiences from then until 30 Nov are as related by F/Lt Dvorak in his report (S/PG/LIB 22).

I remained at the Gestapo Prison, Prague, until 1 Dec when I was moved to the Military prison, Prague. I was kept there until 25 Jan 1945 when I was taken to Stalag Luft 1 (Barth) and released into the main compound.

I was liberated by Russian forces on 1 May at Stalag Luft I (Barth). I was occupied in clearing the aerodrome at Barth until 14 May, when I was sent by air to the UK.

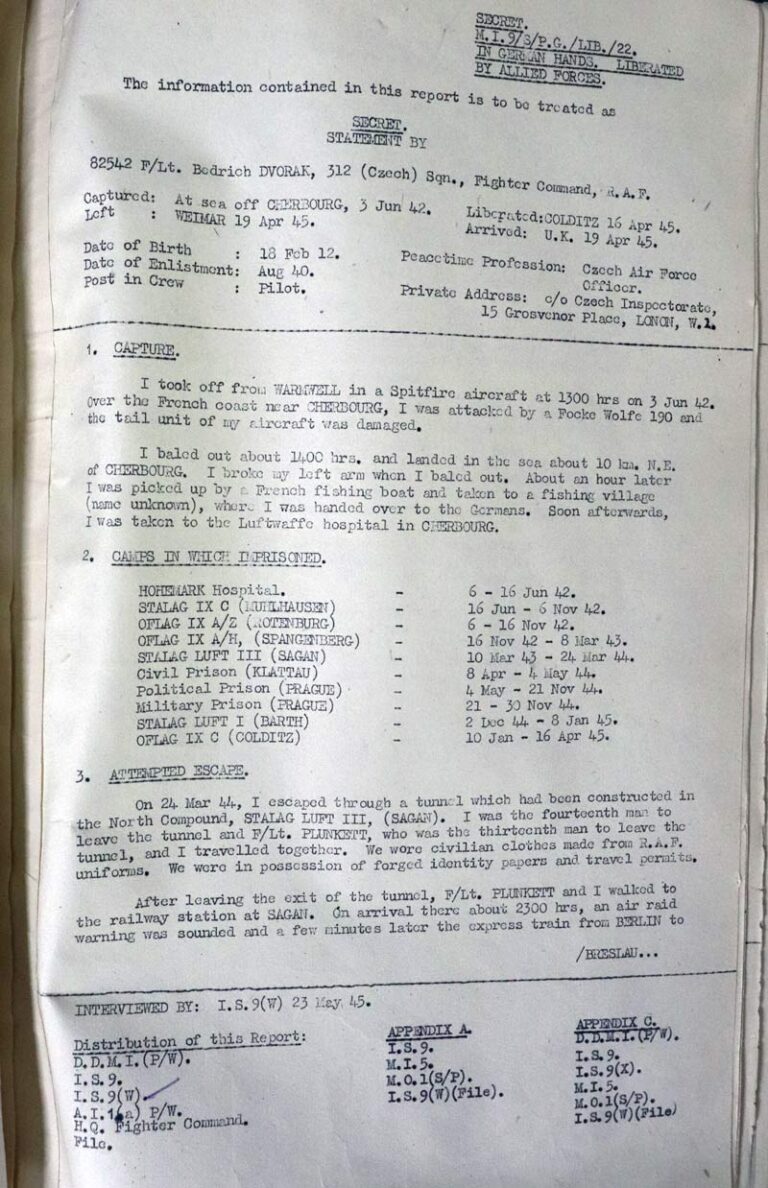

Bedrich Dvorak’s account

Bedrich Dvorak, a Czech, was the fourteenth man out of the tunnel and his report, MI 9/S/PG/LIB 48, also in WO 208/3336, confirms that he and Plunkett exited the tunnel at 2300 hours and then walked to the nearby railway station at Sagan.

On arrival there, the air raid warning was sounded and a few minutes later the express train from Berlin to Breslau arrived. We boarded the train without tickets and travelled (third class) to Breslau. On the train we met S/Ldr [Roger Joyce] Bushell and F/Lt [Bernard W. M] Scheidhauer.

On arrival at Breslau about 0045 on 25 March, we discovered that the train to Glatz on which we had expected to travel at 0100 hrs, had been cancelled. We waited in the booking hall of the railway station until 0600 hrs, when we boarded a train for Glatz. During this time we met and spoke to met S/Ldr Bushell and we saw F/Lt Scheidhauer and met F/Lt [Rupert John] Stevens, South African.

F/Lt Plunkett and I arrived at Glatz about 1100 hrs and travelled by another train (third class) to Bad Reinerz, where we arrived about 1200 hrs. we walked west across the country in the snow to Neu Hradek, where we stayed at a hiotek until the evening of 28 Mar.

We then walked to Neustadtwhere we stayed in a barn attached to a farm until the evening of 1 Apr, when we walked to Spie. We stayed at a farm there until the evening of 2 Apr, when we walked to the railway station at Opocno and travelled by train (third class) to Prague, where we stayed in a hotel the morning of 5 Apr.

We then travelled by train (third class) to Pardubits, where we stayed in a hotel until the morning of 6 Apr and then travelled by train (third class) to Prague, where I made contact with a helper.

We stayed at this man’s home until 7 Apr when we by train (third class) to Klattau, where we were recaptured by Czech police at a railway station on 8 Apr. We were taken to the German police station, where we were kept until 10 Apr. On that day, we were handed over to the Gestapo in Klattau and interrogated. We were kept in cells until 4 May, when we were taken to the Gestapo HQ in Prague, where we were kept until 21 Nov. On that day I was moved to the military prison in Prague, where I remained until 30 Nov. F/Lt Plunkett was not moved with me. On 30 Nov I escorted to Stalag Luft I (Barth), where I arrived on 2 Dec.

A traitor among them?

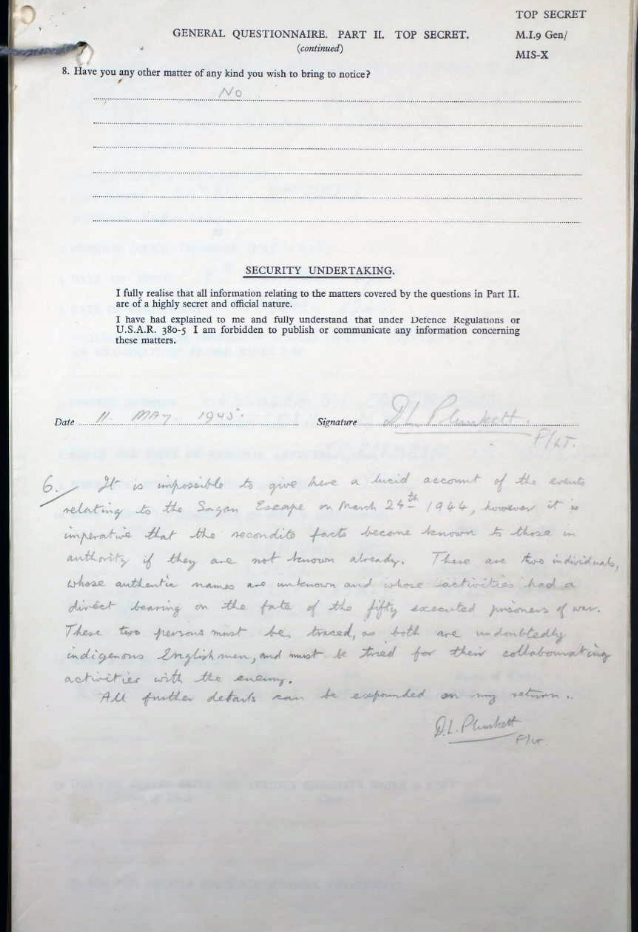

Plunkett’s story then took a remarkable turn. Only three weeks before he submitted his report, he made a sensational allegation on his liberation questionnaire, dated 11 May 1945, and available in WO 344/254/2:

On 6 Jan 1945, the Allied forces arrived at Oflag IV C (Colditz)and I was sent to an aerodrome near Weimar on 18 Apr. On 19 Apr I was sent by air to the UK.

It is impossible to give here a lucid account of the events relating to the Sagan escape on 24/25 March 1944, however, it is imperative that the recondite facts become known to those in authority if they are not known already. There are two individuals whose authentic names are unknown and whose activities had a direct bearing of the fate of the 50 executed prisoners of war. These two persons must to traced as both are undoubtedly indigenous Englishmen, and must be tried for their collaborating activities with the enemy. All further details can be expounded on my return.

This accusation of two ‘indigenous Englishmen’ is the only known one around the murder of the 50 prisoners of war. All prisoners of war completed a liberation questionnaire such as this on their return, Plunkett did his immediately after captivity. His experience had been a particularly harsh one having been held in solitary confinement in Prague for eight or nine months. Following such an ordeal, his state of mind would have been fragile.

Yet, Plunkett’s later report in WO 208/3336 fails to reveal anything further, nor do we know if he mentioned the allegations again.

Blythe’s story

But what of the character of Blythe in the film?

Blythe escapes with the American-born character Flight Lieutenant Robert Hendley, known as the ‘scrounger’ and played by US actor, James Garner. They both travel by train from Zagan, as did Plunkett and Dvorak. But, instead of reaching Prague, Blythe and Henley sneak onto a Wehrmacht airfield and steal a plane to fly over the Swiss border, but the engine fails, and they crash-land. Blythe is shot and killed by German soldiers. Hendley is recaptured and returned to Stalag Luft III.

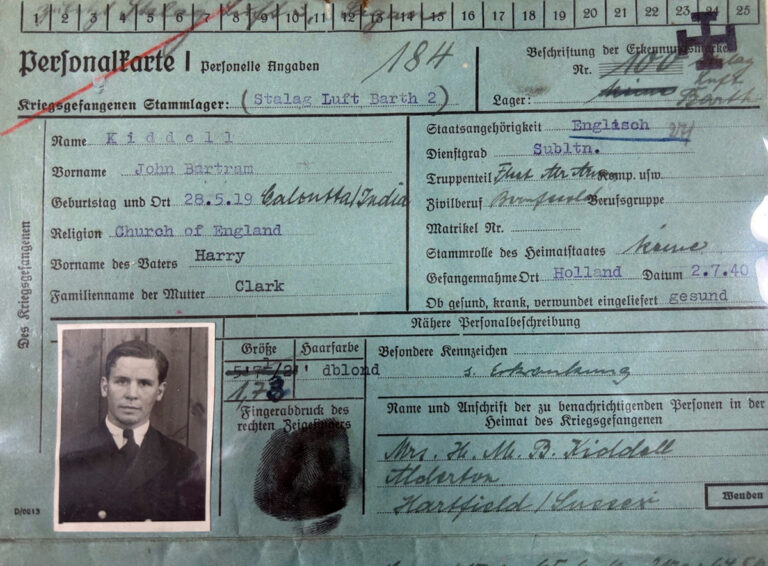

There were many other characters in the film of course, including Flying Officer Archibald Ives, the ‘mole’ played by Scottish actor, Angus Lennie. His character didn’t make it through the tunnel as he was shot dead while trying to scale the fence. Ives was based on Sub-Lieutenant (A) John Bartram Kiddell, of the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy who was shot dead whilst trying to escape from Stalag Luft III in July 1943.

Both the character Ives and the real Kiddell suffered from mental health issues and both deaths were viewed as suicides. Ives, became depressed after the first tunnel, ‘Tom’ was discovered by the guards, and despite warnings, he scaled the perimeter fence before being shot dead by the sentry guard. Kiddell didn’t scale the fence, instead he climbed on to the hospital roof where he had been treated for over four months, and was shot dead after refusing to come down.

The document, ADM 358/179, contains correspondence about Kiddell’s death and state of his mind. One report indicated that he suffered from Dementia Praecox, a condition now known as schizophrenia. The file includes a statement from RAF Group Captain Harry Melville Arbuthnot ‘Wings’ Day, who did escape on the night of the 24 March 1944 only to be recaptured and returned to camp three days later.

Pleasence was the only actor in the film to appear in the made-for-television 1988 sequel The Great Escape II: The Untold Story. In this film, he played the part of real-life Dr Gunther Absalon who was identified as a member of the Gestapo who carried out some of the murders of the fifty airmen in May 1944.

Pleasence lived for many years on Strand on the Green, directly opposite the National Archives at Kew, where his POW records are held. He died on 2 February 1995 and twenty-two years later, a Heritage Foundation blue plaque was unveiled by Air Commodore Charles Clarke OBE who had met Donald Pleasence while filming the Great Escape. Although not directly involved in the actual escape, Clarke was based at Stalag Luft III in March 1944.

Find out more

Find out more about Second World War internment records at our free exhibition Great Escapes: Remarkable Second World War Captives. Closing 21 July 2024, Great Escapes explores the human spirit of hope and resilience during times of captivity, revealing both iconic and under-told stories of prisoners of war and civilian internees during the Second World War.

I was very fortunate to attend a lecture by Squadron Leader ‘Jimmy’ James, one of the ‘Great Escapers’, some years ago. I talked with him for a while, when he told me several very interesting stories. We kept in touch until he died and I will always be so glad that I attended his lecture.

I was fortunate to see Donald Pleasance in his chilling performance on Broadway as Adolf Eichmann in The Man in the Glass Booth.

The world will never again have men and women similar to this “Greatest Generation.”

What an amazing generation of decent and loyal men and women who sacrificed so much for us.

As usual another interesting post.

However ‘a flying officer’ (second paragraph) in this case is a rank and therefore should be written as Flying Officer. His POW card can be found at WO 416/291/510.

It is well-known but worth repeating that while filming ‘The Great Escape’, Pleasence offered advice (based on his experience as a prisoner of war) to the film’s director John Sturges.

This was politely rejected.

Until (so the story goes) Sturges was made aware of Pleasence’s wartime career.