In 2020, to mark the 600th anniversary of the Treaty of Troyes, our medieval specialists dug into our records to find out what happened in 1420. In response to our blog, Professor Sebastian Sobecki of the University of Groningen got in touch with the team to share some interesting findings about the clerks who wrote these documents. One year on, Professor Sobecki shares some of his findings in this guest blog.

When Henry V’s war machine trundled through France it was accompanied by a highly sophisticated mobile bureaucracy. Whereas earlier wars came with their own clerks, the extent and organisational depth of Henry’s overseas administrative structure was unprecedented. The years spent overseeing England’s shifting possessions in France required not only the common set of itinerant royal secretaries and signet clerks, but also representation from the other branches of the Westminster and Windsor bureaucracies, including the Privy Seal and the Chancery. At its zenith the English government’s continental arm included a chancery branch in Rouen that supported a travelling royal council. The government branches most active in France were the Signet and the Privy Seal: in the years prior to Henry’s death in 1422, both writing offices had half of their staff in France, supporting the king and his lieutenants.

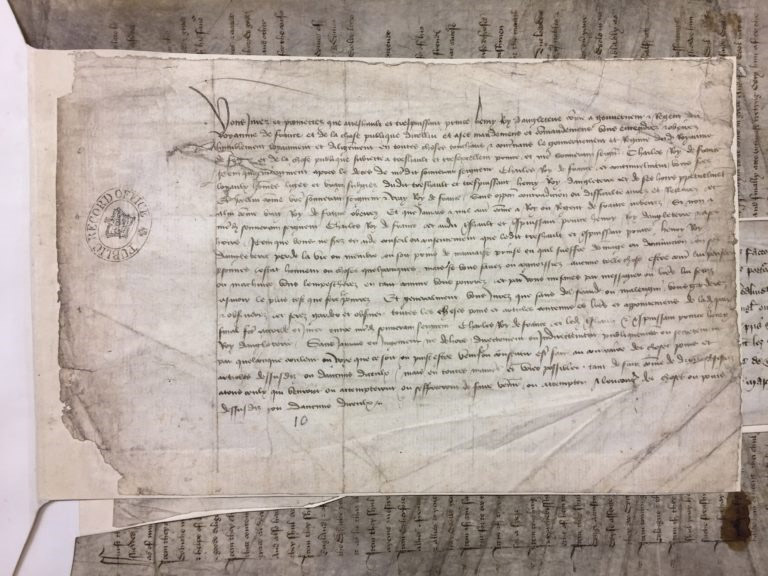

English government in France required the frequent issuance of writs and warrants, the provision of inter-departmental correspondence, and the occasional preparation of treaty charters. For example, the draft oath of the crucial Treaty of Troyes (C 47/30/9), of May 1420, appears to be written in the hand of the Signet clerk William Toly, a friend of the Humanist Poggio Bracciolini. Toly was deployed in France between 1419 and 1422.

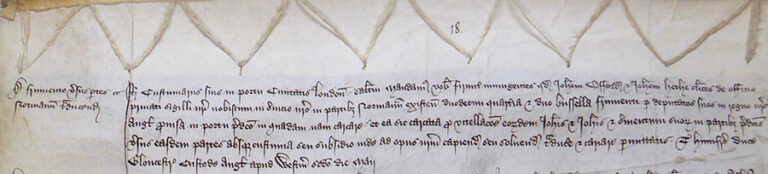

Similarly, the exemplar of the Treaty of Troyes presented to Charles VI, now Paris, Archives nationales, AE III 254, was executed by John Hethe, Thomas Hoccleve’s close colleague at the Privy Seal. Hethe’s name appears on the turn-up of the charter. Pierre Chaplais has shown that in Rouen Hethe also wrote the English royal exemplar of the alliance treaty between Henry V and Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS Moreau 1425, no. 92), and, also in Rouen, Henry V’s privy seal warrant to issue under the great seal a commission appointing Duke Humphrey of Gloucester guardian of England 1. We know from signed writs and customs records that Hethe was in France in 1420.

The presence in France of educated, bookish English clerks who were fluent in French also meant that there was much interaction and exchange with their French counterparts. However, because English was obviously not a lingua franca at the time, this fruitful exchange was usually one-directional and profoundly impactful on the history of English writing and literature. For instance, in the late 14th century, the new Secretary script arrived in England through these channels, whereas English clerks on the continent are also the likeliest route by which French literary works and styles migrated to the British Isles.

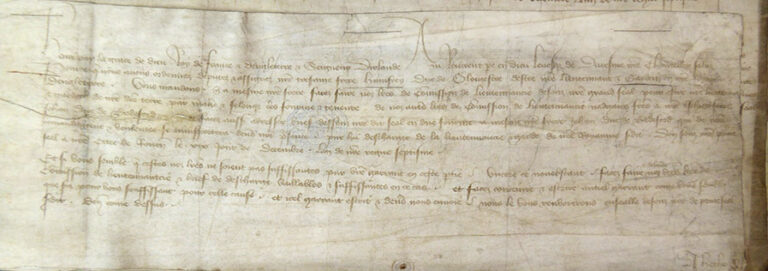

But there also exist numerous private letters sent to England by these clerks. One such letter was sent by John Offord on 6 June 1420 from the siege of Sens to an anonymous recipient in England. The original no longer survives; it was once probably contained in British Library, MS Cotton Caligula D. v. The manuscript was among those badly damaged by the fire of 1731 in Ashburnham House, where the Cotton Library was then located. Andrew Prescott has shown that the Caligula shelfmark was particularly affected by the fire. Many folios in MS Cotton Caligula D. v. have survived, but all of them display burn marks around all four edges. However, Thomas Rymer transcribed and printed the letter in the first edition of his Foedera, a monumental undertaking completed after his death in 1713. Occasionally, this letter is referenced in treatments of Henry’s marriage, Anglo-French relations in Paris, and the minutiae of the ensuing military campaign against the Dauphinist faction 2. The letter has been printed a number of times before, although it has never been edited 3.

In 1916, as part of his work on the Poet and Privy Seal clerk Thomas Hoccleve, Johan Kern identified the author of this letter, who signs himself as ‘Johan Ofort’, with the Privy Seal clerk John Offord, a contemporary and colleague of Hoccleve’s. Kern carefully tethered his identification to the suggestion that a Privy Seal clerk may have been in France with Henry. Offord was indeed with the King in France at the time.

He and his fellow Privy Seal colleague John Hethe were said ‘to be with the king in Normandy on his service’ on 5 February 1420 and were permitted to victual their ship bound for France. Closer to the date of the letter, a writ dated 2 May 1420 confirms that Hethe and Offord were staying with Henry V in Normandy.

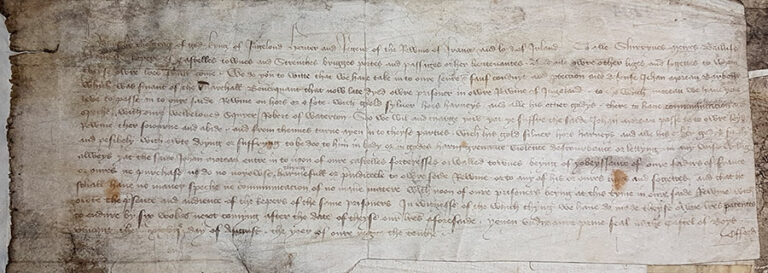

Following my identification of Offord’s handwriting, four records dating from 1422 in his hand (two of which are signed) were given at Paris, Meaux, and Bois de Vincennes. This last location is particularly important: it is a letter patent of safe passage under the privy seal for Jean Moreau, barber to the late Marshal Boucicaut, who had died in captivity in Yorkshire. The warrant was given at Bois de Vincennes, dated 27 August 1422, only four days before the death of Henry V at the same place.

This warrant demonstrates not only that Offord was attending to Henry’s needs as a Privy Seal clerk, but that the king had a full complement of Privy Seal and Signet staff with him even as was on his deathbed. (Richard Caudray, the king’s secretary and head of the Signet Office, was with him, too).

Offord started his career in the Signet before moving to the Privy Seal Office. For much of the first quarter of the 15th century, he was one of four senior clerks together with Hoccleve, John Hethe, and John Bailey. Hoccleve’s Balade to Somer, addressed to the under-treasurer of the Exchequer, Henry Somer, and written between 1408 and 1410, petitions Somer on behalf of the four senior clerks:

We, your seruantes, Hoccleue & Baillay,

Hethe & Offorde, yow beseeche & preye,

‘Haasteth our heruest / as soone as yee may!’

For fere of stormes / our wit is aweye;

Were our seed Inned / wel we mighten pleye,’

And vs desporte / & synge / & make game,

And yit this rowndel shul we synge & seye

In trust of yow / & honour of your name.

(II. 25-32)

We certainly know that Hoccleve and Bailey were close because the latter returned in his will of 1420 Hoccleve’s properties in the village of Hockliffe, in addition to making personal gifts to the poet and his wife 4. The poem itself has been read in the context of the Good of Good Company, a dining society associated with the Temple and the Westminster writing offices, of which Somer, Hoccleve, and probably the other three clerks were members. More importantly, it has long been presumed that Offord also had personal ties to Hoccleve, based on the marginal inscription ‘offord’ on f. 49r of the sole holograph manuscript on Hoccelve’s entire Series, Durham, University Library, MS Cosin V. iii. 9 5. Furthermore, the identification of Offord’s handwriting has made it possible to link his hand to Hand 5 in London, British Library Harley MS 219, the newly identified literary manuscripts containing Hoccleve’s handwriting 6.

At the end of the letter, Offord asks the recipient, who is based in England, to greet four Privy Seal clerks (Abel Hessill, John Bailey, William Alberton, and Richard Priour), one Chancery clerk (Sir John Brokholes), a few others, and the entire group or gang (‘meyne’ in Middle English). Not only are the addressees of these greetings mostly Privy Seal clerks, but Offord’s letter assumes a good deal of familiarity with them: the greetings for Priour include the in-joke ‘whom the fayr Town of Vernon on Seene Gretith Weel also’. Furthermore, the recipient is a close personal acquaintance and is asked to pass on an enclosed letter to Offord’s brother, Piers. The four senior clerks in 1420 were those listed in Hoccleve’s poem above – Hoccleve, Bailey, Hethe, and Offord. Hethe was with Offord in France, Bailey is included in the greetings, but where is Hoccleve? The address at the start of the letter – ‘Worshipful Maistir’ – suggests a recipient who is Offord’s social peer. This is, after all, how Margery Paston writes to her husband John in a letter that ends in the intimate wish for his speedy return ‘for I thynke longe sen I lay in your armes’. At any rate, Offord’s Westminster supervisors cannot be meant because Chancellor Thomas Langley and Treasurer Henry FitzHugh are singled out in an earlier, more formal set of greetings: ‘I prey you that ye wil Recomande me to my Worshipful Loord the Chanceller, and to my Loord the Tresorer’.

Hethe, Bailey, and Hoccleve worked most closely with Offord, who copied a long work into a manuscript overseen by Hoccleve (MS Harley 219) and whose name appears in the margin of Hoccleve’s sole complete holograph copy of the Series. And both manuscripts as well as Offord’s letter date from the early 1420s. The most likely explanation for Hoccleve’s absence from the greetings is that Offord’s letter was addressed to him, the only other senior Privy Seal clerk in England at the time (Bailey is included in the greetings and Hethe was in France).

What does this letter to Hoccleve tells us, then? At the very least, we now know that the poet was exceptionally well informed about the situation in France. He heard the news of Henry and Catherine’s splendid wedding in Troyes, and learned that the Treaty of Troyes was proclaimed in Paris on 27 May 1420, and that Englishmen could now enter the capital without requiring letters of safe conduct. He also found out that Henry wasted no time by leading his army out of Troyes only two days after his wedding, making for the city of Sens. Hoccleve would have also learned that Charles and the French nobility were lodged away from the brutality of the siege to protect their sensitivities. But most importantly, Hoccleve understood the elation and very personal joy in the English camp at the signing of the Treaty of Troyes, not least because Offord reserves capital letters for mentions of the Treaty, calling it by its contemporary moniker, FINAL PEACE, and referring to it as the ‘ACCORD’. This celebratory mood also guides Offord’s wishes for his recipient, in all likelihood Hoccleve himself: ‘I prey God sende Grace to bothe Reumes of much Mirthe and Gladnesse, and yeue you in Helthe much Joye and Prosperitee long to endure.’

Edited text of John Offord’s letter

[6 June 1420]

Worshipful Maistir, I Recomand me to you.

And, as touchyng Tydynges, The Kyng 7 owre Sovereyn Loord was Weddid 8, with greet Solempnitee, in the Cathedrale Chirche of Treys, abowte Myd day on Trinitie Sunday 9.

And, on the Tuysday suyng, he Remeved toward the Town of Sens, xvi. Leges 10 thennes, havyng wyth hym thedir owre Queen and the Frensh Estatz 11.

And, on Wednysday thanne next suyng 12, was Sege leyd to that Toun, a greet Town, and a notable, toward Bourgoyne ward, holden stronge with greet Nombre of Ermynakes 13. The whiche Town is worthily beseged; For ther ly at that Sege two Kynges 14, Queenes 15, iv Ducks 16, with my Loord of Bedeford whanne he cometh hedir 17; the whiche the xii Day of the Monyth of Juyn shall Logge besyde Parys hedirward. And at this Seige also lyn many worthy Ladyes and Gentil women, bothe Frensh and English; of the whiche many of hem begonue the Faitz of Armes 18 long time agoon, but of lyyng at Seges now they begynne first 19.

I prey you that ye wil Recomande me to my Worshipful Loord the Chanceller 20, and to my Loord the Tresorer 21.

And forthermore will the wit that Parys, with other, is swore to obeye to the Kyng owre Sovereyn Loord, as Heriter and Governour of France, and soo they doo.

And on Witsun Munday 22 FINAL PEACE 23 was Proclaymd in Parys; and on Tuysday, the Morrow after, was a solempne Masse of owre Lady, and a solempne Processionn of alle the greete and worthy Men of Parys, thankyng original God of th’ACCORD. And now Englysh Men goon in to Parys, as ofte as they wil, withowte ony saaf Conduyt, or any lettyng. And in Parys, and alle other Townes, that are turned from the Ermynakkes Party, make greet Joye and Myrthe every Halyday in Dauncyng and Karolyng.

I prey God sende Grace to bothe Reumes of much Mirthe and Gladnesse, and yeue you in Helthe much Joye and Prosperitee long to endure.

I prey you that ye wil vouchesaaf to lat this Lettre Comande me to Abel Hoet 24, and Bayly 25, and to Sir J. Brokholes 26, and to grete weel Richard Priour 27 (whom the fayr Town of Vernon on Seene Gretith Weel also) and Will. Albtoo 28 Lark 29, and all the Meyne 30, and Kyng Barbour and hys Wyf 31.

Writen at the Sege of Seens the vi. Day of Juyn in Haste.

Sens is ferther then Parys xxxiv. Leges 32,

And Treys is ferther then Parys xxxvi. Leges 33.

Wil ye sey my Brother Mayster Piers 34 that I sende hym a Lettre be the Brynger heroffe.

Your owne Servant,

Johan Ofort.

Further reading

A L Brown, ‘The Privy Seal Clerks in the Early Fifteenth Century’, in The Study of Medieval Records: Essays in Honor of Kathleen Major, ed. by D A Bullough and R L Storey (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971), 260–81

J A Burrow, Thomas Hoccleve (Aldershot, UK: Variorum, 1994), iv

Pierre Chaplais, English Medieval Diplomatic Practice, 3 vols (London: HMSO, 1975-82)

Gwilym Dodd, ‘Trilingualism in the Medieval English Bureaucracy: The Use—and Disuse—of Languages in the Fifteenth-Century Privy Seal Office’, The Journal of British Studies, 51 (2012), 253–83

J Otway-Ruthven, The King’s Secretary and the Signet Office in the XV Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1939)

Malcolm Richardson, ‘Hoccleve in His Social Context’, The Chaucer Review, 20 (1986), 313–22

Sebastian Sobecki, ‘The Handwriting of Fifteenth-Century Privy Seal and Council Clerks’, Review of English Studies, 2020

Sebastian Sobecki, Last Words: The Public Self and the Social Author in Late Medieval England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019)

Sebastian Sobecki is Professor of Medieval English Literature and Culture at the University of Groningen.

Notes:

- Sebastian Sobecki, ‘The Handwriting of Fifteenth-Century Privy Seal and Council Clerks’, Review of English Studies, 2020, 5; Pierre Chaplais, English Medieval Diplomatic Practice: Part I, Documents and Interpretation, 2 vols (London: HMSO, 1982) ii.636, n331. ↩

- See, for instance, Guy Llewelyn Thompson, Paris and Its People Under English Rule: The Anglo-Burgundian Regime, 1420-1436 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991), 217. ↩

- The printings include John Lingard, A History of England from the First Invasion by the Romans to the Accession of Henry VIII, 3 vols (London: Mawman, 1819), iii, 375n; Agnes Strickland, Lives of the Queens of England, from the Norman Conquest, 6 vols (London: Bell and Daldy, 1864), i, 510–511; Jessie Hatch Flemming, England under the Lancastrians (London: Longmans, Green, 1921), 58; Lætitia Lyell, A Mediæval Post-Bag (London: J. Cape, 1934), 274. ↩

- Sebastian Sobecki, Last Words: The Public Self and the Social Author in Late Medieval England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 65–100. ↩

- On this inscription, see Sobecki, Last Words, 96–98; Rory G. Critten, Author, Scribe, and Book in Late Medieval English Literature (Cambridge: D S Brewer, 2018), 58; David Watt, The Making of Thomas Hoccleve’s Series (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013), 58–61; J A Burrow and A I Doyle, eds., Thomas Hoccleve: A Facsimile of the Autograph Verse Manuscripts, EETS SS 19 (Oxford: Oxford University Press for the Early English Text Society, 2002), xxxi. ↩

- Sobecki, ‘The Handwriting of Fifteenth-Century Clerks of the Privy Seal’, 9–11. For the discovery of Hoccleve’s hand in Harley 219, see Misty Schieberle, ‘A New Hoccleve Literary Manuscript: The Trilingual Miscellany in London, British Library, MS Harley 219’, The Review of English Studies, 70/297 (2019), 799–822. ↩

- Henry V. ↩

- Henry married Catherine of Valois, the daughter of Charless VI of France, in Troyes Cathedral on 2 June 1420. ↩

- Trinity Sunday fell on 2 June since Easter Day 1420 occurred on 7 April. ↩

- The unit ‘league’ was never commonly used in England, but it roughly corresponds to 3 miles. Sens is 59.4 km/37 miles from Troyes. This suggests that Henry’s forces needed at least two days to reach Sens if they left in the morning of 4 June. Offord’s letter was therefore written on their arrival at Sens. ↩

- Having cancelled a tournament the day after his wedding, Henry left Troyes on Tuesday, 4 June, to restart the military campaign against the Dauphinist party. He was accompanied by the Queen, King James of Scotland, and Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy (Jonathan Sumption, The Hundred Years War, Volume 4: Cursed Kings [London: Faber and Faber, 2017], chap. 17). ↩

- The siege of Sens lasted from Wednesday, 5 June, until 11 June (Nicholas Hooper, Nick Hooper and Matthew Bennett, The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: The Middle Ages, 768-1487 [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996], 131). Some sources give 10 June as the date of the surrender (Craig Taylor, ‘Henry V, Flower of Chivalry’, in Henry V: New Interpretations, ed. by Gwilym Dodd [Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 2013], 237). ↩

- France was embroiled in a civil war at the time between the Burgundian party, which was allied to the English and included the French king Charles VI, and the Armagnacs (‘Ermynakes’) who were led by the Dauphin, Charles, count of Ponthieu. However, the garrison defending Sens was only 300 strong and vastly outnumbered by Henry’s combined forces of 8,000-10,000 men (Sumption, The Hundred Years War IV, chap. 17). ↩

- There were actually three kings in attendance: Henry V, Charles VI, and John I of Scotland. ↩

- The two queens were Catherine of Valois and Isabelle of Bavaria, Charles’ wife. ↩

- Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, and the Duke of Bedford were certainly present. The other two are probably the dukes of Clarence and Exeter, who were with Henry at Troyes. Louis III, Count Palatine of the Rhine, though not a duke, was also in attendance. ↩

- The Duke of Bedford and his contingent of soldiers joined Henry’s forces at Sens (Sumption, The Hundred Years War IV, chap. 17). ↩

- Feats of arms, i.e., battle. ↩

- According to the author of the anonymous Vita et gesta Henrici quinti, Charles and the queens were in Villeneuve-le-roi, south of Paris, to protect them from having to witness the brutality of the siege (Thomas Hearne, ed., Thomæ de Elmham Vita & gesta Henrici Quinti, Anglorum regis [Oxford, 1716], 268–269). Offord’s comment appears to confirm the account of the Vita et gesta, hinting at the possibility that certain nobles were uncomfortable with the presence of these women at the siege. ↩

- Thomas Langley, Bishop of Durham. ↩

- Henry FitzHugh, third Baron FitzHugh. ↩

- 27 May. ↩

- The Treaty of Troyes, signed on 21 May, was referred to as the ‘final peace’ (C T Allmand, ‘The Coronations of Henry VI’, History Today, 32/MAY [1982], 28–33; Christopher Allmand, Henry V [Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1992], 152). ↩

- Probably Abel Hessill, Privy Seal clerk. ↩

- John Bailey, Privy Seal clerk. ↩

- Sir John Brokholes, a Chancery clerk. Offord granted Brokholes power of attorney on 20 January 1420 in connection with his departure for France (TNA C 76/102, m. 5). ↩

- Richard Prior, Privy Seal clerk. ↩

- William Alberton, Privy Seal clerk. ↩

- Lark is unidentified, though it could be a transcription error by Rymer. ↩

- ‘Meyne’ means ‘group’. ↩

- King Babour and his wife are unidentified. ↩

- The amounts given here underestimate the actual distance from Paris and the difference between the two destinations. Sens is 100.6 km / 62.5 miles from Paris. ↩

- Troyes is 141.3 km / 87.8 miles from Paris. ↩

- A Piers Offord has not been identified. ↩