![Parchement document showing the ratification by Charles, King of France, of the Treaty of Troyes, 21 May 1420 [Catalogue reference: E 30/411]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20130457/E30-411-Ratification-of-the-Treaty-of-Troyes-21-May-1420-blog-768x716.jpg)

21 May 2020 marks the 600th anniversary of the Treaty of Troyes, a peace treaty which sought to unite the crowns of England and France under one king – Henry V – and his heirs, and end the Hundred Years War. To mark the anniversary, our Principal Records Specialists in the Medieval team dug into our records to find out what happened in Troyes in 1420, and why the treaty ultimately failed.

The Background to 1420

The rivalry, frequently enmity, between the crowns of England and France in the Middle Ages has a long history. The most famous (not to say infamous) and prolonged period of conflict, which rumbled on for much of the 14th and the first half of the 15th centuries, is known to historians (if not mathematicians) as the Hundred Years War.

Between the first eruption in 1337 and the final expulsion of English presence from France (bar Calais) in 1453, English armies campaigned regularly on French soil and the naval power of both countries was harnessed at sea, often bringing terror to coastal communities. Both sides and their allies engaged in sieges and pitched battles, and the English notoriously used devastating, lightning fast raids into the French countryside called ‘chevauchées’.

Nevertheless, given the issues at stake – and the frequent stalemates and necessity to recover from warfare and bouts of plague and famine that swept western Europe in this period, both sides also reached for diplomatic measures to gain an advantage. Embassies (often to the pope), truces and, ultimately, treaties formed an integral part of Anglo-French relations.

The main areas of contention were, firstly, the status of those lordships within France that were claimed by the English crown, notably Gascony in the southwest, which remained in English hands from the 12th century to the 15th, and Normandy, lost by King John in 1204 and then temporarily regained by Henry V, exceeding the territorial gains even his great-grandfather Edward III had made.

Secondly, from the fourth decade of the 14th century, England exercised a dynastic claim to the throne of France. This originated in the marriage of King Edward II (1307-27) and his queen, Isabella (c. 1295-1358), daughter of the French king, Phillip IV (1268-1314), and the birth, in 1312, of Edward of Windsor, later Edward III. A series of tragic early deaths beset the French royal house; Isabella survived her elder brothers and through her son, so the English asserted, carried a claim against the Valois house, the line emanating from Philip’s younger brother, Charles (d. 1325), which took the French throne in 1328.

English armies under Edward III, as is well-known and rehearsed in history, literature, film and art, enjoyed memorable victories at Crécy in 1346 and Poitiers in 1356. At Poitiers, the French king John II was taken captive and imprisoned in England, until ransomed in 1360 in the peace Treaty of Brétigny. This imposed a huge ransom and awarded Edward III significant land gains in France. Once breached in 1369, the conflict reverted to campaigning, raiding and, ultimately, stalemate that lasted effectively into the early years of the 15th century.

That stalemate was shattered by outbreak of war after King Henry V (1413-22) came to the English throne. Henry V’s seismic victory at Agincourt in 1415 opened the way for a new occupation of Normandy, the establishment of garrisons and the more affirmative exercise of a claim to the French throne. It put the English king firmly in the ascendant.

Troyes and the Treaty

In France, the assassination of the Duke of Burgundy in 1418 had left the way open for a truce and an end to the war. The new duke, Phillip the Good, and the French queen, Isabeau, were willing to form an alliance with England in order to end the ongoing war, and to secure a strong presence on the French throne.

It was agreed that Phillip, Isabeau (acting on behalf of the king, Charles VI, who was often incapacitated with bouts of mental illness) would meet with Henry V at Troyes in May 1420 – with limited numbers of men on either side – to seal a peace treaty intended to unite the crowns of England and France in perpetuity.

![Parchment roll showing the army sent under the duke of Bedford in 1420 [Catalogue reference: E 101/49/36]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20131442/E-101-49-36-m3-768x1024.jpg)

The records for this agreement, as well as the muster rolls for the English expedition to Troyes, are held in our collections, and give details of the army who travelled to the proceedings.

By the terms of the treaty Henry would marry Charles’s daughter Catherine of Valois, and would inherit the French throne as heir after the French king’s death.

‘It is agreed that after our death and from that time forward, the crown and kingdom of France, with all their rights and [privileges], shall be vested permanently in our son[-in-law], King Henry [of England], and his heirs … Now and for all time, perpetually to quieten, calm and in all respects end all dissensions, hatreds, grudges, enmities and war between…the Kingdoms of France and England’

Treaty of Troyes (Catalogue ref E 30/411)

This was not to be a full integration of the two kingdoms – the institutions of each kingdom, and issues such as taxation remained separate – rather a dual monarchy: one king with two crowns. In the meantime, Henry was to act as regent, but not to name himself as King of France, while Charles VI’s son (also Charles), the Dauphin, was also disinherited for his ‘great and shocking crimes and misdeeds’.

‘[Article 29] In consideration of the great and shocking crimes and misdeeds committed against the Kingdom of France by Charles, who is called Dauphin…it is agreed that ourselves, our…son King Henry and also our very dear son Phillip, Duke of Burgundy, will never negotiate in any way for peace or any sort of agreement, with the said Charles’

Treaty of Troyes (Catalogue ref: E 30/411)

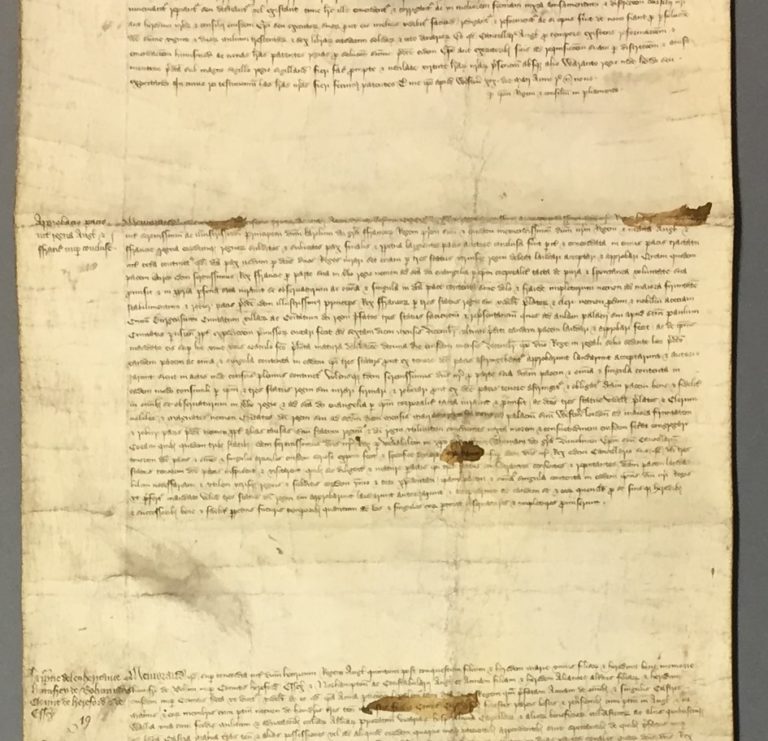

After the treaty had been sealed, the French nobility swore an oath of allegiance, followed by the inhabitants of Troyes. Draft copies of this oath are preserved in our collections among the Chancery miscellanea (series C 47).

![Old document showing the draft oath of the Treaty of Troyes [Catalogue reference: C 47/30/9]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20133213/C-47-30-9-10-blog-768x576.jpg)

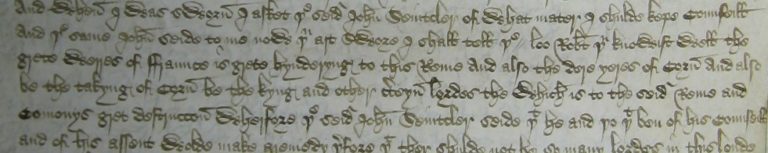

The day after the treaty had been agreed, Henry wasted no time in writing home to England to declare the success of the treaty, and to announce his new title and styling in Latin, English and French.

‘Henricus dei gracia Rex Anglia heres et Regens regni Francie et Dominus Hibernie

Henry V’s titles and styling after Troyes (Catalogue ref: C 54/270)

Henry by the grace of god kyng of England heire and Regent of the Rewme of Ffrance and lorde of Irelande

Henry par la grace de dieu Roy dengleterre heritier et Regent du Royaume de Ffrance et seigneur dirlande’

![Parchment roll, showing Henry V's titles and styling in a letter written after Troyes [Catalogue reference: C 54/270]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20133506/C54-270-m17d-titles-768x170.jpg)

In the same letter Henry wrote of the ‘joyful tidings of our good speed touching the conclusion of peace between the two realms’ enclosing a copy of the treaty to be proclaimed in London and throughout England.

![Parchment roll showing Henry V's letter to England in the aftermath of Troyes [Catalogue reference: C 54/270 m17d]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20133901/C54-270-m17d-letter-768x441.jpg)

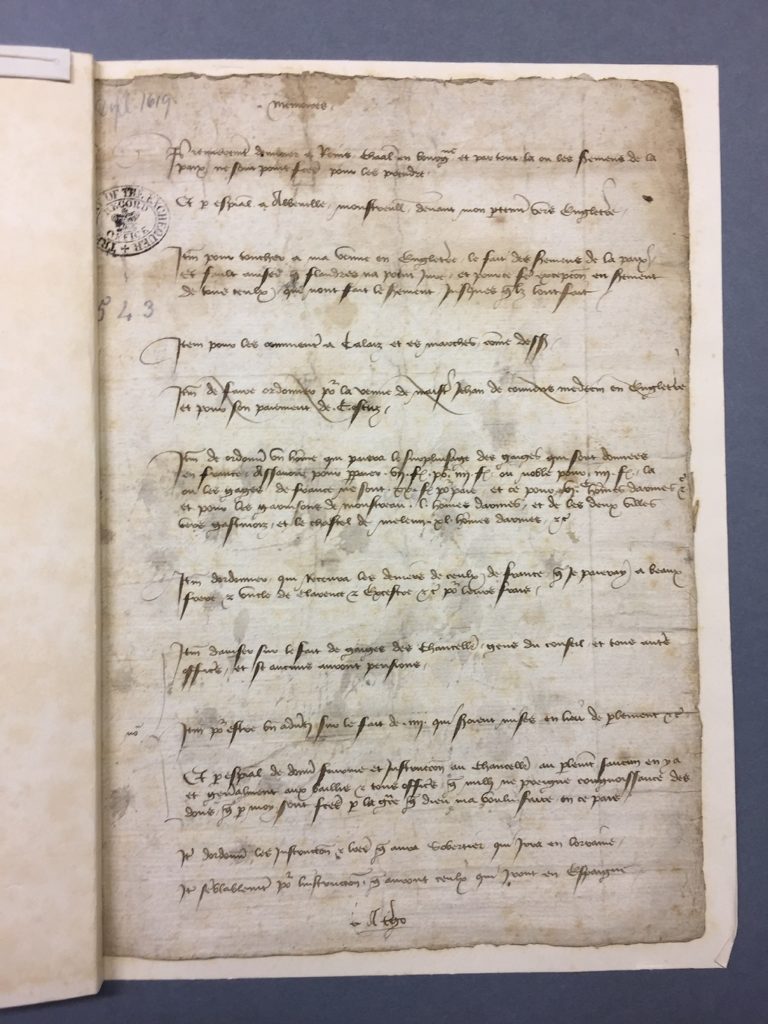

In the immediate aftermath of the treaty, however, peace was not assured, and Henry was soon back in action attempting to subdue opposition within France. But his mind remained on returning to England. An aide-memoire written in French (but probably dictated by Henry), which dates from between May and November 1420, refers to his (hoped) upcoming departure to England (mon partement vers Engleterre), as well as ‘the money of those of France that I will pay to my brother and uncle of Clarence and Exeter’.

While Henry remained at war in France, he was now technically not at war with France, merely involved in a French civil dispute, which had implications in terms of taxation, a theme which the parliament assembled in December 1420 were keen to emphasise. They were also enthusiastic about the potential future financial opportunities arising from the treaty, most notably the possibility of charging a toll to navigate the channel[ref]C 65/81. A full transcription and translation of the ratification can be found in ‘Henry V: December 1420’ in Parliament Rolls of Medieval England, ed. Chris Given-Wilson, Paul Brand, Seymour Phillips, Mark Ormrod, Geoffrey Martin, Anne Curry and Rosemary Horrox (Woodbridge, 2005), British History Online (British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/parliament-rolls-medieval/december-1420).[/ref].

‘Whereas our most sovereign lord the king and his noble progenitors have forever been masters of the sea, and now, by grace of God, it is the case that our said lord the king is master of the coasts on both sides of the sea; to ordain that on all foreigners travelling across the said sea a charge be imposed for the use of our said lord the king, such as seems reasonable to him, for the safeguard of the said sea’ – December 1420

Parliament Roll for December 1420 (Catalogue ref: C 65/81)

Henry would eventually arrive back in England on 1 February 1421, with his new wife crowned as queen in Westminster abbey on 23 February. Not long after, the parliament of May 1421 was summoned, where the treaty was ‘approved’ by the English almost a year after its sealing in Troyes. This ratification, while recorded on the parliament roll, had already been approved by a preliminary meeting of the ‘three estates of the realm’ (as in the French tradition) in the lead up to parliament meeting.

Having gained ratification of his treaty in parliament, it wasn’t long before Henry was back on campaign again, leaving England for France in June 1421. But this time he wouldn’t return, dying in August 1422 (possibly from dysentery contracted in the unsanitary environment of a medieval siege). Charles VI died a few months later, in October 1422 leaving the two crowns of England and France in the hands of a 10-month-old infant – Henry VI – who had been born at Windsor Castle in December 1421, and who had never even met the father whose treaty brought him the French crown.

Legacy of Troyes

So what was the legacy of the Treaty of Troyes? Well in the short term, not a lot would change. The Duke of Bedford remained on campaign in France against the Dauphin’s supporters, and in 1423 the Treaty of Amiens re-iterated the terms of Troyes, recognising Henry VI as King of France. In 1431 Henry was even crowned as King of France in Paris, but the location of the ceremony is a testament to changing English fortunes.

The traditional location for the coronation of French kings was Rheims, but in 1431 the area was under opposition control, leaving Henry to settle for Paris. And it would only get worse, with Henry’s inability to lead English troops in battle in his father’s image being just one of many factors which would see him lose the majority of his French lands as the 15th century drew on.

The poor English fortunes in France feature time and time again in our medieval legal collections, as opposition to Henry and his advisors was voiced by those defying his rule. This dissension – made worse by bouts of mental incapacity from the king – would grow throughout the century, particularly in the late 1440s and 1450s as English forces lost town after town in France, leaving Calais as the sole continental holding from 1453. Seditious pub talk, and treasonous plots to murder the king and his top nobles, frequently mention the wars in France as a motivating factor for those caught and tried.

![Parchment document setting out treasonous talk against Henry VI: "[he said] that the king was a natural fool and would oft times hold a staff in his hands with a bird on the end playing therewith as a fool, and that another king must be ordained to rule the land, saying that the king was no person able to rule the land" [Catalogue reference: KB 9/122, m. 38]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20141747/KB9_122-m.28-1-768x377.jpg)

Henry VI’s failings in France would ultimately end up being one of the factors which would spark civil war in England – the Wars of the Roses – less than half a century after Henry V’s success at Troyes. Henry’s usurper, Edward IV, would attempt one final attempt at the French crown in 1475 but instead chose to pursue peace with Louis XI after the Treaty of Picquigny, in return for a substantial payoff and pension for himself and some of his nobles.

In 1558 the final English outpost in France, Calais was also lost, recognised in a new Treaty of Troyes in 1564. While English monarchs would continue to claim the crown for themselves until the 19th century, the claim was largely abandoned in practice. Henry V’s dream of two kingdoms, united under one crown, was finally over.

Of course it was the divine intervention of Jeanne d’Arc in 1429-1431 to save France which rescued the future Charles VII by her victory at Orleans on 8 May 1429 and his coronation in Reims (not the English spelling as Rheims) Cathedral and European history was never the same as before despite Jeanne’s death at Rouen in May 1431. The 100th anniversary of Jeanne’s canonisation in Rome in the Vatican in May 1920, one of the biggest canonisations was last week .

The English did not murder Jeanne d’Arc but she was executed by the French. ( blasphemy) I am sure many on this site know this but if you go on to ‘site seeing’ walk around Rouen , as I have, you do not hear the truth, if you are English.