Content note: This blog contains references to slavery and the system of indenture in the Caribbean, quoting original documents from the 19th century that contain racist language and ideas. The original wording has been preserved here to accurately represent our records and to help us understand the past.

As Migration and Citizenship researcher at The National Archives, I have been tracing the stories of those aboard the Empire Windrush in 1948. Out of over 1,000 people aboard in 1948, 802 gave their last place of residence as somewhere in the Caribbean and 693 planned to settle in Britain. Passengers aboard also lived in Burma, Africa, Norway and Northern Ireland. 66 were Polish refugees who had been displaced by war over four years prior, having travelled via Iran, Uzbekistan and India before eventually arriving in Tampico, Mexico.

As I investigated further, I was surprised to see that the Passenger list also records East Asian names. Individuals like Edwin Ho, who participated in friendly boxing matches onboard and found work in Telford in the Midlands, or Clinton Wong, a member of the RAF, who was based at RAF Sealand, which is now MoD Sealand near Chester. What could we make of these other stories – that some might not associate with Windrush-generation migration – and what might they tell us about the journeys of migration that predated the post-war period?

Finding individuals from the passenger list in the records at The National Archives was a challenging task, and name searches through Discovery produced little if any traces. None of the passengers aboard listed their last place of residence as China, or any country in Asia. In fact, people from China had settled in the Caribbean over a hundred years prior. To find out more about the Chinese community and their descendants, then, I had to travel further back in time through the archives.

An established system of labour

As early as 1803, over thirty years before the ending of slavery in the British empire, Kenneth MacQueen, who had been appointed to explore the possibility of transporting Chinese workers to Trinidad, wrote to the commissioner regarding the idea of recruiting a ‘numerous’ contingent of Chinese workers as indentured workers.

Broadly, indenture is a process whereby an individual is bound to work for a set amount of time for an employer. Only upon the completion of their tenure are labourers permitted to leave, and occasionally workers complete multiple terms. Indentured labourers have few rights, are often unable to leave their places of work and are often treated poorly. Projects at The National Archives have already started to investigate the history of Indian indenture in the British West Indies from the mid-19th century (see footnote 1).

In the British Empire indenture was already considered a highly effective system of labour, such as the successful colony on the island of Penang off the coast of Malaysia (named ‘Prince of Wales Island’ by the British at the time). In 1804 there were around 6,000 settled Chinese workers there, who successfully cultivated pepper, nutmeg and other spices (see footnote 2).

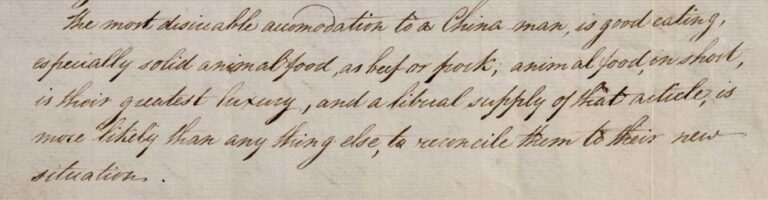

The Chinese were preferred as a workforce as it was believed they were industrious and would cope well with the Caribbean climate. Below, MacQueen discusses what the Chinese labourers will need in order to ‘reconcile them to their new situation.’ (See footnote 3.)

Kenneth MacQueen advises that Chinese labourers would be content, just as long as they were provided with ‘solid animal food’. The placation of labourers through their stomachs is recommended to ‘reconcile them to their new situation’, suggesting that the conditions that awaited those arrivals was far from comfortable. MacQueen, who at this moment in time was regarded in Britain as a person with significant experience and relationships with the Chinese, offers flawed advice, underpinned by colonial thinking, justified by the economic needs of planters in the Caribbean.

Despite the level of wealth that indenture generated for the British Empire, and although the Chinese were transported to the Caribbean as a ‘free people’, workers had few rights and were subject to harsh penal laws. In 1871 the poor conditions of Indian and Chinese indentured workers in British Guiana, now the nation of Guyana, led to the Chief Justice of British Guiana from 1863 to 1868, Joseph Beaumont, to publish a book The New Slavery, in which he strongly criticised the system of indenture (see footnote 4).

Sustaining a racial hierarchy

Key to the recommendation of transporting labourers from Asia to the British West Indies was the belief that the Black enslaved population and Asian peoples would not ‘mix’ and start families (see footnote 5). In a secret memorandum from the British Colonial Office to the Chairman of the Court of Directors of the East India Company, John Sullivan, the colonial administrator in 1803, wrote:

‘… no measure would so effectually tend to this danger, as that of introducing a range of free cultivators into our islands, who, from habits and feelings could be distinct from the Negroes’

Colonial Office Correspondence, catalogue ref: CO 295 (see footnote 6)

The comments reflect the highly racialised organisation of indenture. The ‘danger’ Sullivan mentions refers to the uprising in the Dutch colony of St Domingo, otherwise known as the Haitian Revolution, where enslaved peoples revolted against their colonial masters. Beyond Sullivan’s fears over an uprising, maintaining racial purity and sustaining a racial hierarchy were incredibly important to the colonial project of Empire, ensuring the continuation of Britain’s global dominance (see footnote 7).

The introduction of Chinese indentured labourers to the British West Indies would sustain the capitalist production of goods and weaken the position of enslaved people by providing an alternative source of labour. However, early attempts to transport Chinese labourers and put them to work on plantations in Trinidad were largely unsuccessful in the eyes of the British government. Only a small community of 113 Chinese remained on the island one year after the first transport in 1806 (see footnote 8).

Histories of labour mobility, diaspora and globalisation intertwine. Alongside sporadic flows of migrant labour from China to the Caribbean in the early 19th century, indentured labourers from India – some two million – also took up contracts across the British Empire (see footnote 9).

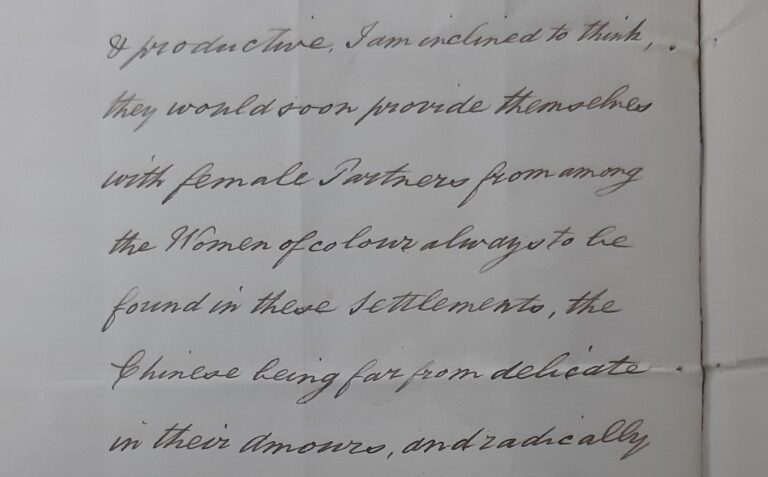

Many former indentured labourers decided to remain in the Caribbean after their period of indenture, starting businesses and settling down to start families, some with enslaved women (see footnote 10). Consequently, communities of Indo Caribbeans and Afro-Chinese in the Caribbean increased during the 19th and 20th centuries.

‘A minority within a minority’

Unfortunately, tracing indentured labourers and their descendants in the archive is extremely difficult as only first names, if any at all, were recorded by the government (see footnote 11). Portraits of experiences from the perspective of labourers themselves are extremely rare (see footnote 12). Nonetheless, at The National Archives, research into the history of indenture has already pieced together the stories of those behind the ‘Great Experiment’ and how we might receive them today (see footnote 13).

We can presume that descendants of these communities, and those connected to indenture, did end up on the Windrush in 1948 and travel to Britain, or elsewhere, in subsequent crossings, and in journeys predating 1948. Although migrating to Britain may have represented a form of ‘homecoming’ for Indo Caribbeans who were British subjects, the arrival of the descendants of indentured labourers often faced a kind of double racial exclusion, in what Maria del Pilar Kaladeen calls ‘a minority within a minority’ (see footnote 14).

The diversity of the Caribbean, captured partially by the Empire Windrush passenger list in 1948, reveals historic and global flows shaped by imperial ambition and capitalist desires. As we continue to develop our understanding of migration to Britain in the post-war period at The National Archives, we might also begin to understand how individuals like indentured labourers in the 19th century created new lives for themselves across the globe.

Footnotes

- See the research guide on Indian indentured labourers in The National Archives.

- B. W. Higman, ‘The Chinese in Trinidad, 1806 –1838’, Caribbean Studies, Vol. 3, No, 4 (1972): 21- 44. CO 295/2, fols. 205r & v, W. Layman, Hints for the Cultivation of Trinidad, 16 July 1802. Variations of indenture continue to be in use today.

- CO 295/6, folios 150-1.

- Joseph Beaumont, A New Slavery: An Account of the Indian and Chinese Immigrants in British Guiana (W. Ridgeway, 1871).

- For more on the colonial experiment of Chinese indenture that was intended to create a ‘buffer race’ between the white minority and black majority in the Caribbean after the ending of slavery, see Tao Leigh Goffe, ‘Albums of Inclusion: The Photographic Poetics of Caribbean Chinese Visual Kinship’ Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 22, no. 2 (2018): 35-56.

- Own emphasis added, ‘Secret Memorandum from the British Colonial Office to the Chairman of the Court of Directors of the East India Company’, Colonial Office Correspondence, CO 295, vol 17. See also BT 6/70.

- Stephen Howe, ‘Empire and Ideology’, in S. Stockwell (ed.), The British Empire (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2008), 166.

- B. W. Higman, ‘The Chinese in Trinidad, 1806-1838’ Caribbean Studies 12, no. 3 (1972), 33.

- Crispin Bates, ‘Some Thoughts on the Representation and Misrepresentation of the Colonial South Asian Labour Diaspora’, South Asian Studies 33, no. 1 (2017), 7-22.

- A labourer by the name of Aho cohabited with an enslaved woman called Eliza Clement. Upon his death in 1829 he left Eliza $350 to purchase her freedom, as well as all his furniture and his clothes, in his will. Will of Aho, 11 June 1829, quoted by B.W Higman ‘The Chinese in Trinidad, 1806 – 1838’, 40.

- For more information, see the research guide on Indian indentured labourers in The National Archives.

- Letters from indentured workers provide a rich resource for researchers. For example, Marina Carter, Voices from Indenture: Experiences of Indian Migrants in the British Empire (Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1996).

- See The National Archives collaborative project with BAATN (Black, African and Asian Therapy Network).

- Maria del Pilar Kaladeen, ‘Hidden histories: Indenture to Windrush,’ British Library, October 2018.

This is so interesting and very readable. I didn’t know about indentured workers during that time. It is fascinating to know the links with Chinese people and the Windrush generation. Thanks for doing this research!

Thank you Rachel. To find out more check out Iqbal Singh’s blogs on Indian indenture and the challenges of research.

Excellent to have such accurate historical data out there and available to read and be included in our national discussions. Well done. Thanks.

Thank you Jane. All the records cited in this blog are available to view at Kew with a readers ticket. Here you can find out more about visiting us.

Very interesting and well written. Isn’t it always baffling to read about how our ancestors treated people from “inferior” ethnicity?

Really amazing to see these stories being researched and written about so articulately, especially as a person with parents from both Penang, Malaysia and Guyana. My ancestors likely came to Guyana as Indian and Chinese indentured labourers but there are little known facts. Currently trying to write about these stories creatively and this has inspired me to go digging at the National Archives! Many thanks

Thanks Chloe. I am a descendant of Chinese migrants to British Guiana. Only found out about our family story in 2021. Reading British government papers from the 19c and their plans of experiment: moving Chinese and Indian communities to the British Caribbean is difficult as our ancestors are anonymous and dehumanised by the system of indenture. Thanks for highlighting and sharing.

An interesting additional complication is that not everyone on the Windrush was a migrant. Clinton Wong was my grandfather, born in Guyana and a descendant of both Chinese indentured laborers and African chattel slaves. He had also already settled in England before his time on the Windrush, so his voyage was a literal homecoming rather than a metaphorical one; he had been visiting family on a leave from the RAF.