Content note: This blog includes descriptions of violence during war, including references to sexual violence, which some people may find upsetting.

Katrina Lidbetter volunteers at The National Archives cataloguing records relating to British and Allied Prisoners of War during the Second World War. In this blog she explores a series of nominal cards that highlight the experiences of those impacted by the 1941 invasion of Hong Kong. The series has recently been catalogued by our volunteers and can now be searched by name.

– Padej Kumlertsakul, Adviser for Overseas and Defence, The National Archives

On 8 December 1941, the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese forces launched an all-out assault on Hong Kong, then a British colony. Following 18 days of brutal fighting, the defending troops surrendered and Hong Kong fell. The Japanese military occupation began.

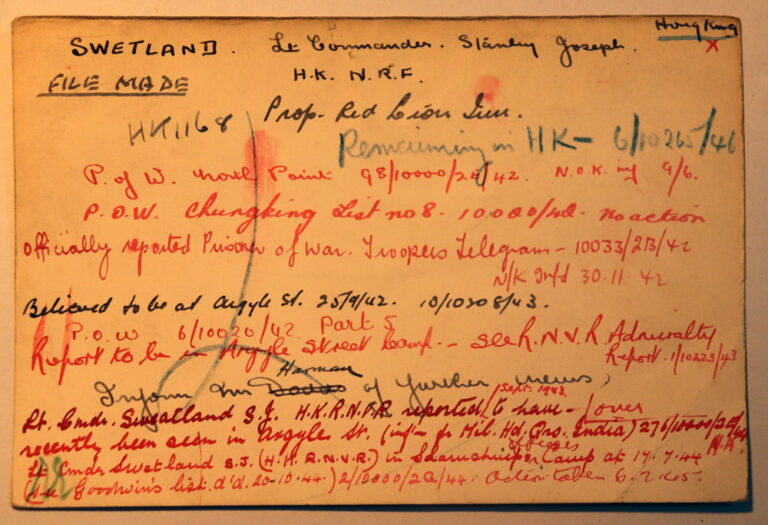

The stories and lives of those upended by the events in Hong Kong are detailed in Series CO 1070, recently catalogued by volunteers at The National Archives. The series comprises of nominal cards – or index cards used to record information – created by civilian internees and some prisoners of war who were seized following the invasion. Following the project, the cards are now catalogued by name of individual creating over 4,250 individual records. These include people like Joseph Swetland who took up arms against the invaders; Brenda Morgan who treated the wounded; and those interned, such as Dr Talbot who tried to get money for those in need. As the records show, their lives, and others, were forever changed.

Facing the horrors of war

The cards, handwritten, in pen, pencil and crayon, show that details of death or internment were often only discovered months or even years after the event. They show the desperate scramble for any information about survivors and are a testimony to the chaos that overwhelmed the island. Some cards bear good news: they are overwritten with scrawled details of survivors’ long journey home after the war, most by ship, some by air.

The cards include employment details. These read like a gazetteer of trades in Hong Kong before the war – all the businesses that you’d expect to find in a busy flourishing international port in 1940, such as dock workers; police and customs; a petroleum company; public bodies such as water works, the post office, the prison, schools and the university; food processing, such as a sugar refinery; and religious organisations such as missions, convents and a cathedral. There are some familiar names such as Thomas Cook and Sons, the Singer Sewing Machine Company, the Salvation Army, American Express, the Bata Shoe Company. As well as British and Chinese, there are people of many other nationalities.

Also listed are job titles: from brokers, tea traders, shipwrights, junk inspectors, accountants, shopkeepers and clerks to university lecturers, priests, nuns, teachers, doctors, and nurses.

The battle for Hong Kong

All these ordinary people were pitched into the full horrors of war when, just after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, the Japanese launched their attack on the mainland defence lines around Hong Kong. These were held by British, Canadian and Indian Army Regiments, plus a few RAF planes. The waters around were protected by a few Navy vessels. These forces were supported by the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps and Naval Volunteers, both young and old – some had served in the First World War.

Clerks, accountants, lawyers, and others left their day jobs and took up their guns to defend the Colony. People like Joseph Swetland, the proprietor of the Red Lion Inn, who was also a Lieutenant Commander in the Naval Reserve (CO 1070/7/351: pictured). They put up a brave fight, but the result was inevitable. Attacked by overwhelming forces, many paid with their lives, on the battlefield, or injured and then bayoneted by the Japanese who often did not take prisoners. Joseph’s card shows that he was captured and taken to a prisoner of war camp, and fortunately survived the war.

Caring for the injured

Many wives had enrolled as Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) Nurses. There were also military nurses: the elite Queen Alexandra Imperial Nursing Service (QAs), who were working at Bowen Road Military Hospital. As injured people flooded in, this hospital was soon under bombardment. Neighbouring buildings were pressed into service. One such was St Albert’s Convent under its New Zealand matron, Kathleen Thomson (CO 1070/7/468), where QA Brenda Morgan (CO 1070/5/463) was nursing. A direct hit killed Brenda and seriously injured Kathleen. Despite the dangers, nurses and doctors continued to work.

As the Japanese surged forward on Christmas Day, another hospital at St Stephen’s College, a former boys’ school, lay on the front line and witnessed terrible atrocities. Survivors gave an account after the war to the Tokyo War Crimes Trial. Nurses and doctors were attacked, some nurses raped, doctors and nurses murdered, patients bayonetted. Nurse Ida Andrews-Levinge (CO 1070/4/557) survived and gave testimony after the war: her testimony is in the Imperial War Museum.

The surrender

The surrender of Hong Kong on 25 December brought some small relief to the hospital. Surviving staff and wounded were rounded up to be interned. Elsewhere in the Colony, the cards show that surviving soldiers were taken as prisoners of war to terrible military camps across Japanese-held territory. Some died in transfer, including most of those shipped on the Lisbon Maru, which was sunk.

Most civilians were held at Stanley Road Camp. Although many families had been evacuated, usually to Australia, many, unaware of the danger, stayed too long. Whole families ended up in Stanley Road Internment Camp. Despite the conditions, there were even some marriages and births.

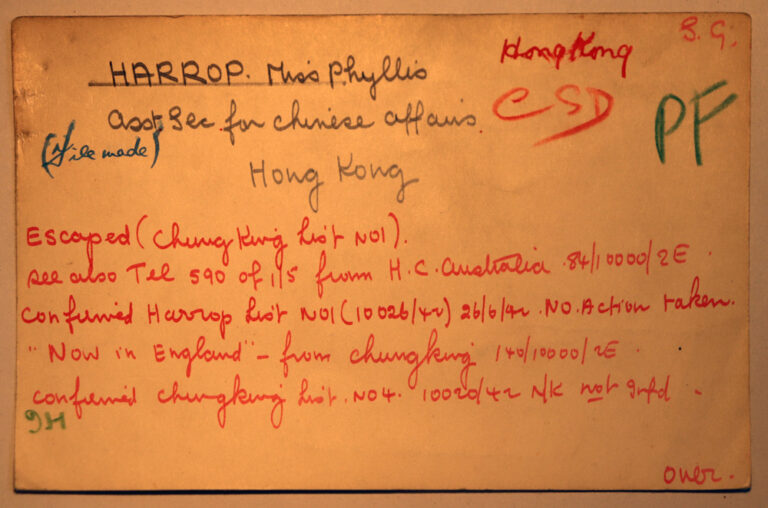

Few escaped – just surviving was challenge enough. However, for some their nationality protected them. Phyllis Harrop (CO 1070/3/438: pictured), a civil servant in Hong Kong, had been married to a German national. Like other government officials, she was not immediately interned but given administrative work by the Japanese. She did not tell the Germans she was now divorced and managed to get a pass, which enabled her to board a ferry and leave in January 1942. She went to Chungking, taking with her lists of the internees that she had been putting together under Japanese orders.

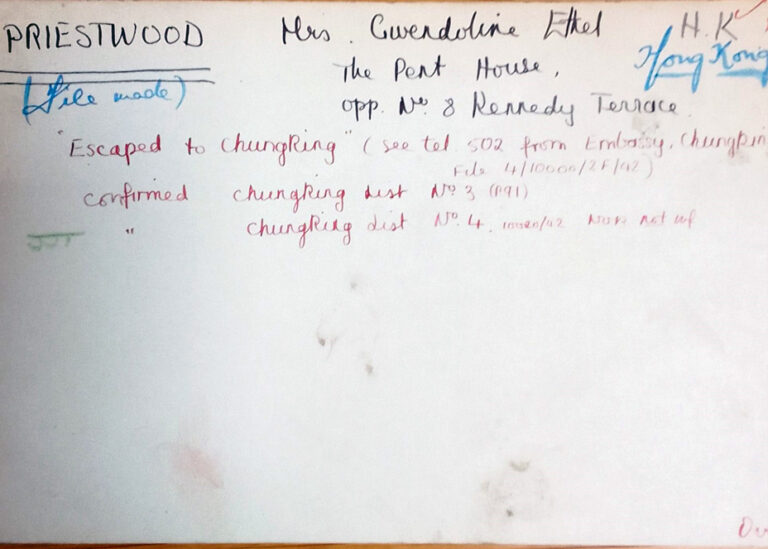

A few even escaped from internment. Police Superintendent Walter Thompson (CO 1070/7/455) and Gwendoline Ethel Priestwood, nee Fullbrook (CO 1070/6/398: pictured), a secretary and volunteer nurse, who met in Stanley Road internment camp and resolved to team up and escape. Thompson spoke Cantonese. Equipped with revolver, compass and map, they crawled under the barbed wire on 19 March 1942 and – helped by a fishing junk and the Chinese guerrillas – reached Free China. Hidden with her, Priestwood carried lists of the Stanley Camp internees to the British in Free China’s wartime capital, Chungking.

Getting supplies to Stanley

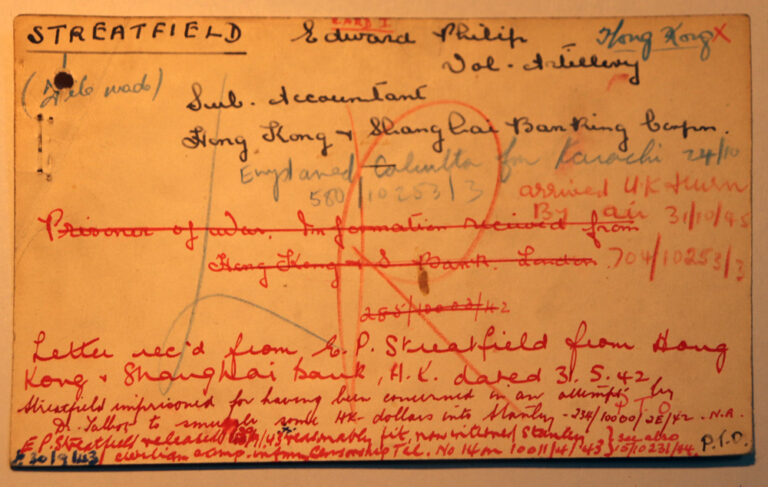

One group of civilians were not immediately interned. These were Hong Kong’s bankers, who were required by the Japanese to liquidate the banks. With enormous courage, several used the opportunity to get food and money to buy essential supplies into Stanley Road Camp. They included Sir Vandeleur Grayburn (CO 1070/3/221), Chief Manager of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC), and Edward Streatfield, a senior accountant at HSBC (CO 1070/7/300 – pictured).

Some money was smuggled in by Dr Talbot via St Paul’s Hospital (CO 1070/7/365). Tragically Talbot was caught and with incredible courage, Grayburn and Streatfield approached the Japanese to say that they had given the money to Dr Talbot to improve conditions in the camp and that it was from American internees who had been repatriated in July 1942. Along with other brave souls they were imprisoned and tortured. Grayburn died but Talbot and Streatfield survived and were released to Stanley Camp in September 1943.

Further resistance

Others took resistance to the Japanese further. Charles Frederick Hyde (Ginger) (CO 1070/4/87) another banker, not only smuggled food but also listened to an illegal radio and was in touch with the Resistance. He was caught, imprisoned and beheaded by the Japanese on 29 October 1943. His wife Florence Eileen Hyde (nee Burgess) and their son Michael were interned but Florence died of cancer during her internment. Florence was friends with Lady Grayburn, wife of Sir Vandeleur, and she adopted Michael. They survived internment but Michael died in an accident in the 1950s.

Despite overcrowding, disease, malnutrition and the cruelty of their guards, most internees in Stanley Camp survived their grim ordeal. They found different ways to make their internment more bearable, some risking their lives to defy the Japanese.

Edward Irvine Wynne-Jones, the Postmaster General (CO 1070/4/229), spent time secretly designing a victory stamp (pictured). He was helped in this by William Ernest Jones (CO 1070/4/243) – not a relation – but the chief draughtsman at the Public Works Department. After the war, Wynne-Jones took his hand-drawn stamp back to Britain and King George VI gave permission for this to be a special issue. The only change needed was the date: Wynne-Jones had over-optimistically put 1944 as the year of liberation.

This is the first of a two-part blog on Series CO 1070 highlighting the work by volunteers at The National Archives, which now sees the records catalogued by name of individual, creating over 4,250 individual records.

References and further reading:

- Philip Cracknell: The Battle for Hong Kong (2021); and The Occupation of Hong Kong (2022)

- Nicola Tyler: Sisters in Arms (2008)

- 81 years ago: Hong Kong’s wartime diaries | Gwulo

- Edward Irvine Wynne-Jones – The Thrifty Traveller (wordpress.com)

- Hong Kong – 1946 Peace Issue | National Postal Museum (si.edu)

Find out more

Find out more about Second World War internment records at our upcoming free exhibition Great Escapes: Remarkable Second World War Captives. Open until 21 July, Great Escapes explores the human spirit of hope and resilience during times of captivity, revealing both iconic and under-told stories of prisoners of war and civilian internees during the Second World War.

We’ve also scheduled a season of special events to accompany the exhibition that are available to book.

what stars you are for all of this wonderful work – thank you

Brilliant stuff. Keep up the good work YTNA and volunteers.

Who Knew about the Japanese war crimes trial, I guessed there had to be a trial but it did not enter my consciousness. Do you have any more info. about this at the NA.

Although the calendar date of the Hong Kong attack was December 8, and the Pearl Harbour attack December 7, because they lie on opposite sides of the International Date Line, the Hong Kong attack was mere hours after Pearl Harbour rather than a full day later. The earliest event of the Japanese war as probably the landing at Kota Bharu, just after midnight Malaya time. My father was the editor of the Hong Kong newspaper China Mail, and received the message on the wire service at 4:00 am, December 8, Hong Kong time, that Pearl Harbour was under attack, just in time to stop the presses and make a new headline.

This is wonderful to see, thank you for your hard work organising this archive. The IWM London has my father’s (Major John Monro MC RA) account of the battle of Hong Kong, his internment and escape across China. He was made Assistant Military Attaché in Chungking and spent 18 months supporting and trying to liberate the PoWs he’d left behind. I also wrote about his story in Stranger In My Heart (Unbound 2018). Happy to share these with you if you like.

A big thank you to all the volunteers! The Battle of Hong Kong lasted only 18 days and resulted Hong Kong being the first British colony fallen into the hands of the enemy by force in 200 years. We saw people of different ethnicities and nationalities put themselves forward selflessly to the defence of this city, and many of them sacrificed their lives as a result. Those who survived the battle then had to fight for their survival during the Japanese occupation, which lasted 3 years and 8 months. Their stories must not be forgotten. Thank you all for keeping the stories alive.

It is felt that the extraordindary work of Mr John Pownall Reeves, O.B.E., HM Consul at Macao during the war, especially his tireless effort in organising relief for British refugees who escaped from Hong Kong and took shelter in Portuguese Macao, needs to be mentioned. Being 6,000 miles away from the UK with only a skeleton of staff and scarce resources, and the Japanese were literally at the doorstep, he managed to look after 10,000 people (my family included) throughout the war. The lack of mention of his work in the official account of the history does not do justice to him and his team.

Total respect,for every one who were there, when Hong Kong fell to the enemy. Rest in peace to all never made it home. My friends,uncle on the Libon Maru.his body wss never found.

I have just found out today that my 2nd cousin was killed in action in Hong Kong some time between the 8th and 25th of December 1941,

and is buried in the war cemetery.

William Reginald Bailey.

Thank you very much for your work on this website.

Martin Bailey.