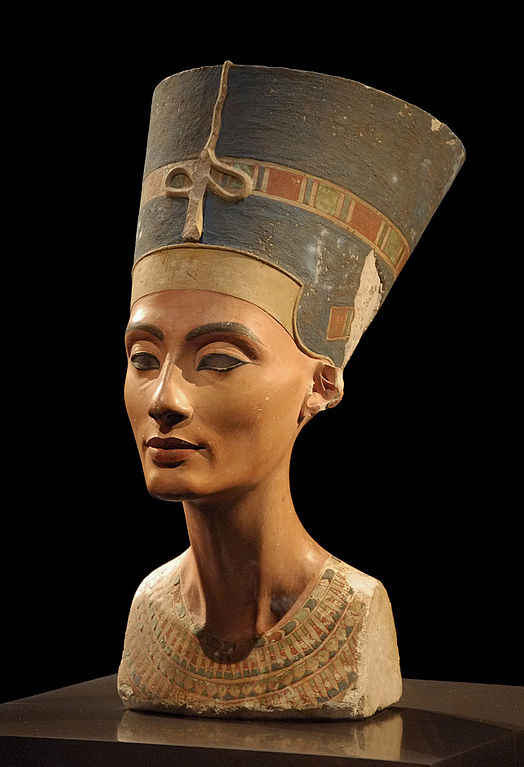

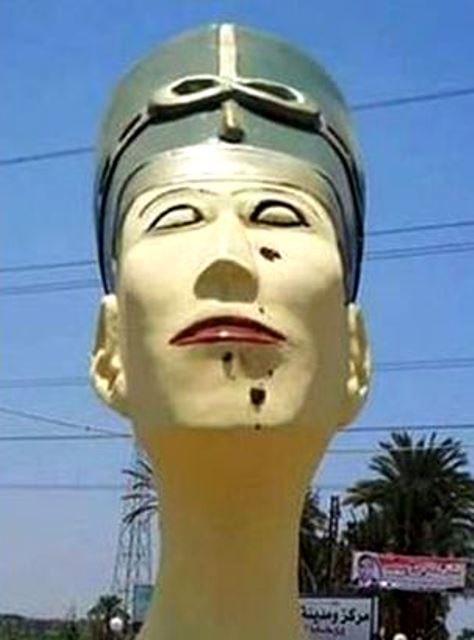

Bust of Queen Nefertiti, Neues Museum, Berlin (image: Wikimedia Commons)

Anglo-French rivalry, a touch of Germanophobia, two world wars and a flawless artefact. This is the background of what became known as the Nefertiti Affair.

Even if you have never set foot in Egypt or you’re not sure why Nefertiti’s name rings a bell, you’ve probably seen her face somewhere. With the golden mask of Tutankhamun, the bust of Queen Nefertiti, now displayed in the Neues Museum in Berlin, is one of the best known pieces of Egyptian art. It was discovered in 1912 in Tell el-Amarna by German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt, of the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft, and has never ceased to fascinate since 1923, when it was displayed for the first time.

In December 1918, the London-based Egypt Exploration Fund (EEF, now the Egypt Exploration Society) expressed an interest in excavating at Tell el-Amarna, the capital of Pharaoh Akhenaten (best known for having tried to impose a quasi-monotheistic cult of the sun) and his wife Nefertiti (FO 141/589).

Pierre Lacau, the (French) Director of the Egyptian Antiquities Department, initially wanted to keep the site (FO 141/589). In March 1919, he acknowledged that the Department was overworked and stated he was prepared to grant a concession to excavate. However, he explained, the site was of great archaeological importance (bear in mind he didn’t know about Nefertiti!), and the antiquities discovered there should really not be scattered. In 1912, he said, the Germans had discovered a sculptor’s workshop; abiding by the terms of the concession which granted the excavators half the objects discovered, the Antiquities Department had to divide the objects equally while they should have been considered as a whole. He added:

‘in that respect, we have nothing specific to blame the Germans for: they have used the right the Government had generously granted them at its own expense.’ (FO 371/3724)

Lacau also explained that he had already received excellent applications for Tell el-Amarna and that he wasn’t sure why the EEF should have precedence. Either way, Lacau continued, he wanted to make sure the concession would be granted to a ‘disinterested scholar’ who would put the advancement of science before the rather vulgar issue of compensation. He therefore had two absolute preconditions. There would be no 50:50 division of the objects (excavators would only receive what the Department wouldn’t want to keep), and the discoveries couldn’t be given away to private collectors nor scattered amongst different museums. He also asked all applicants to submit a detailed programme of work (FO 371/3724).

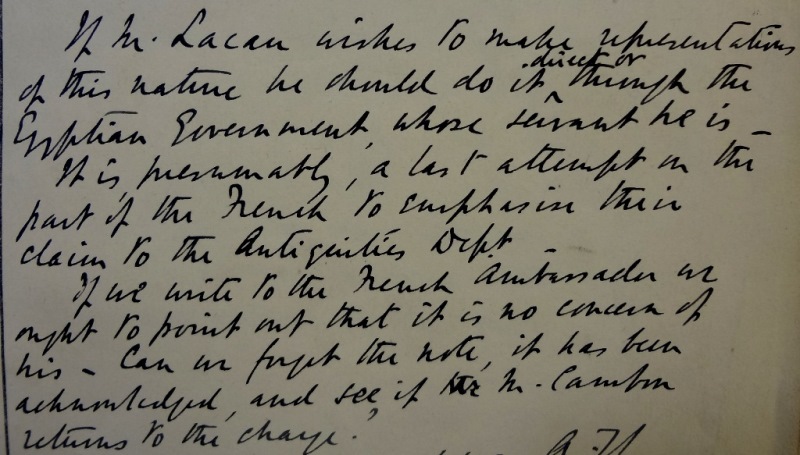

In April, Paul Cambon, the French Ambassador to London, wrote to the Foreign Office to support Lacau’s conditions. The old spectre of Anglo-French rivalry raised its ugly head again. ‘If we write to the French ambassador’, the Egyptian Department commented, ‘we ought to point out that this is no concern of his’ (FO 371/3724).

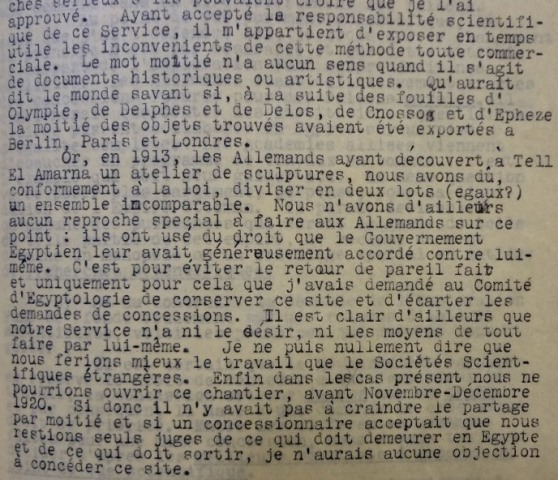

Foreign Office minute, 16 May 1919 (catalogue reference: FO 371/3724)

The Committee of the EEF then sent a memorandum, explaining why they found themselves ‘in disagreement with Monsieur Lacau’s view in several respects’. They made scathing comments on the Antiquities Department (understaffed) and the Cairo Museum (overstocked), and claimed that Britain’s position in Egypt entitled them to ‘a certain prior right (primus inter pares) as regards opportunities of archaeological work in Egypt’ (FO 371/3724).

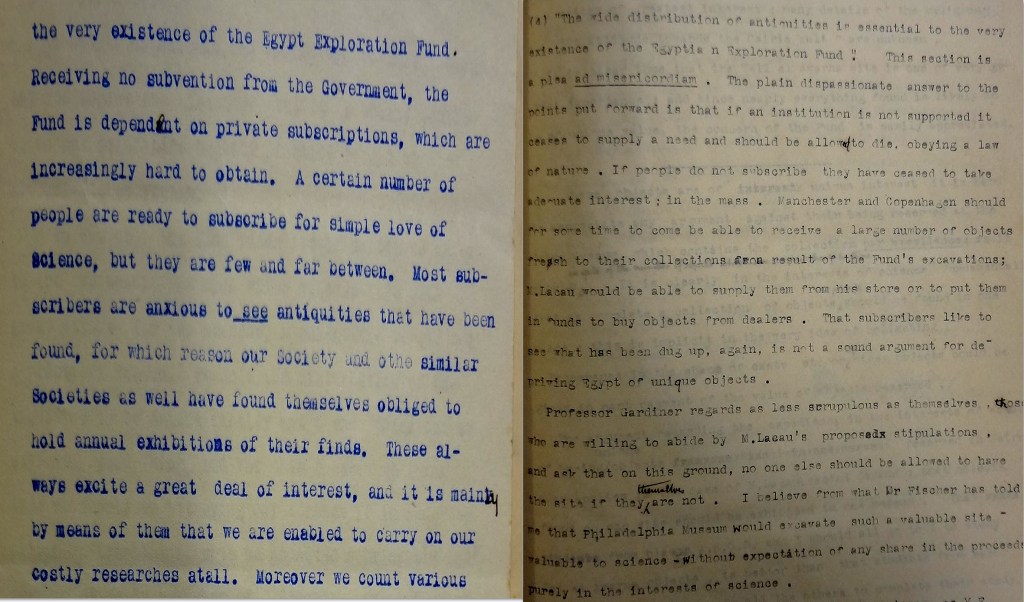

In October 1919, they sent another memorandum, highlighting some of the points previously made, and claiming plaintively that obtaining a fair share of objects and distributing them was ‘essential to the very existence of the Egypt Exploration Fund’. People could be very generous, they said, but they wanted to see what they had paid for.

Ernest Thomas, of the Egyptian Ministry of Finance, wasn’t impressed. Describing the text as a ‘plea ad misericordiam’, he stated bluntly:

‘the plain dispassionate answer to the points put forward is that if an institution is not supported it ceases to supply a need and should be allowed to die, obeying a law of nature.’ (FO 141/589)

Egypt Exploration Fund’s memorandum of October 1919 and Ernest Thomas’ note of January 1920 (catalogue reference: FO 141/589)

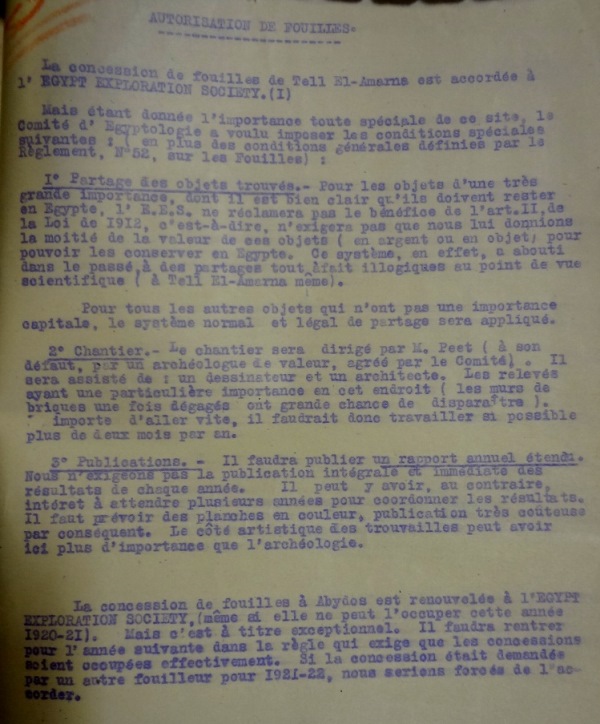

In May 1920, Lacau informed the EEF that George Reisner, of Harvard, had accepted his conditions but that he would rather grant them the concession, provided they accepted the same terms. Under strong political pressure, he even compromised, renouncing to demand that the objects shouldn’t be scattered. The concession was finally granted on 15 June 1920 (FO 141/589).

Excavation permit granted to the Egypt Exploration Fund, 15 June 1920 (catalogue reference: FO 141/589)

Thomas, who had decidedly very little time for the EEF, immediately commented:

‘it is regrettable in the interest of science that the E. E. Fund should have been accorded the concession when a highly qualified and experienced archaeologist was willing to do the work (and it is unlikely that the E.E. Fund can do it as well as he) on M. Lacau’s terms.’ (FO 141/589)

I’m sure you’ll be reassured to know that the EEF did an excellent job.

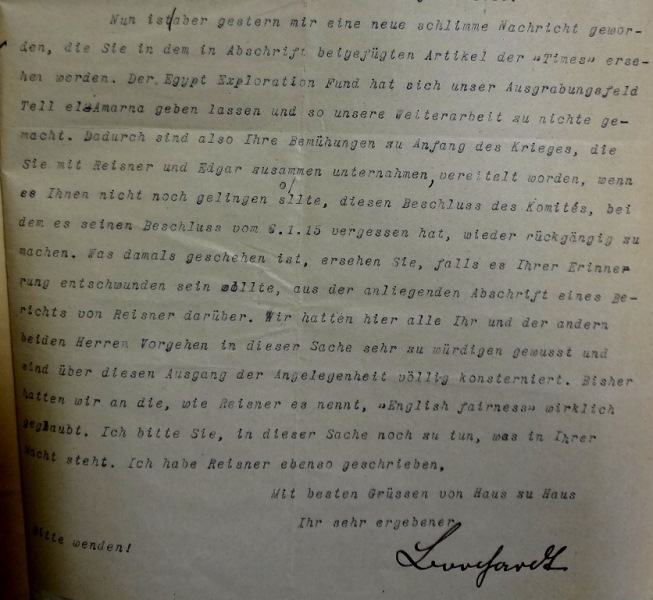

A month later, Ludwig Borchardt, who was painfully aware of the potential of the site, complained bitterly (and somewhat whiningly) to James Quibell, curator at the Cairo Museum. He was already fighting to get the German Institute in Cairo back, he wrote, and found it very trying. He added:

‘And now I have received yet another piece of bad news, which you can read about in the enclosed article from the Times. The Egypt Exploration Fund has been given our excavation site of Tell el-Amarna, and therefore shattered our hopes of conducting further work there.’ (FO 141/589)

In 1919, Lacau, who had spent the war in the trenches and was stridently anti-German, had claimed that, as far as Tell el-Amarna was concerned, he had ‘nothing specific to blame the Germans for’. This changed dramatically when the bust of Nefertiti was revealed to the world in 1923. Lacau kicked off a campaign to get it back, which is still going on. He went as far as banning German archaeologists from excavating in Egypt.

In June 1927, Nevile Henderson, the acting High Commissioner, reported that the German Minister in Cairo was under ‘unofficial’ pressure to return Nefertiti to Egypt. He feared it might be a ‘test case’, and that the Egyptian government would soon try to recover artefacts from other museums.

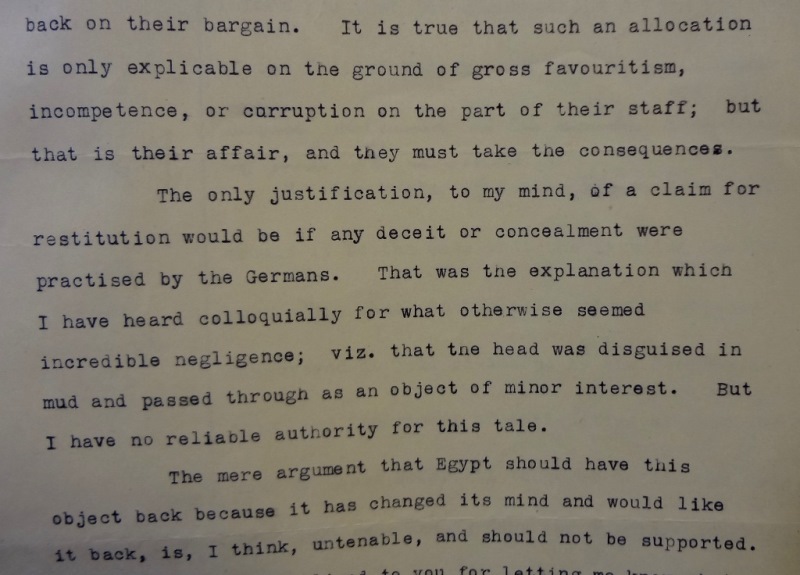

The Foreign Office turned to the British Museum for advice. Sir Frederic Kenyon’s reply was rather blunt. He was against the restitution of Nefertiti unless it could be proved the Germans had been deceitful at the time. He reported a rumour was circulating in egyptological circles, according to which the head had been covered in mud and passed through inspection as an object of minor interest. He added that it was the Antiquities Department’s problem, and concluded:

‘it is true that such an allocation is only explicable on the ground of gross favouritism, incompetence or corruption on the part of their staff; but that is their affair, and they must take the consequences.’ (FO 371/12388)

Kenyon to Murray, 19 July 1927 (catalogue reference: FO 371/12388)

At the beginning of December 1927, The Evening News’ Cairo correspondent reported that the issue would be submitted to arbitration. The Foreign Office felt it would set a precedent and commented, somewhat dramatically: ‘the Rosetta Stone and the Elgin Marbles are in danger!’ (FO 371/12388). The Reichstag rejected the idea at the end of January 1928 (FO 141/440).

The issue was raised again in 1929, when King Fuad of Egypt went on an official visit to Germany. Despite raging debates in the press, Nefertiti wasn’t mentioned during the visit (FO 371/13878).

On 9 April 1930, the Sunday Times reported that the Cairo Museum had ‘made offers for an exchange which, if officially confirmed, would probably be regarded by Berlin as acceptable’, especially as Egypt would also lift the ban on German excavations. Kenyon thought Berlin may well accept the deal. The objects offered were of great archaeological importance and museum curators, ‘suspicious of the charms of mere prettiness’, would probably find them appealing. Stephen Gaselee, the Foreign Office Librarian, was horrified:

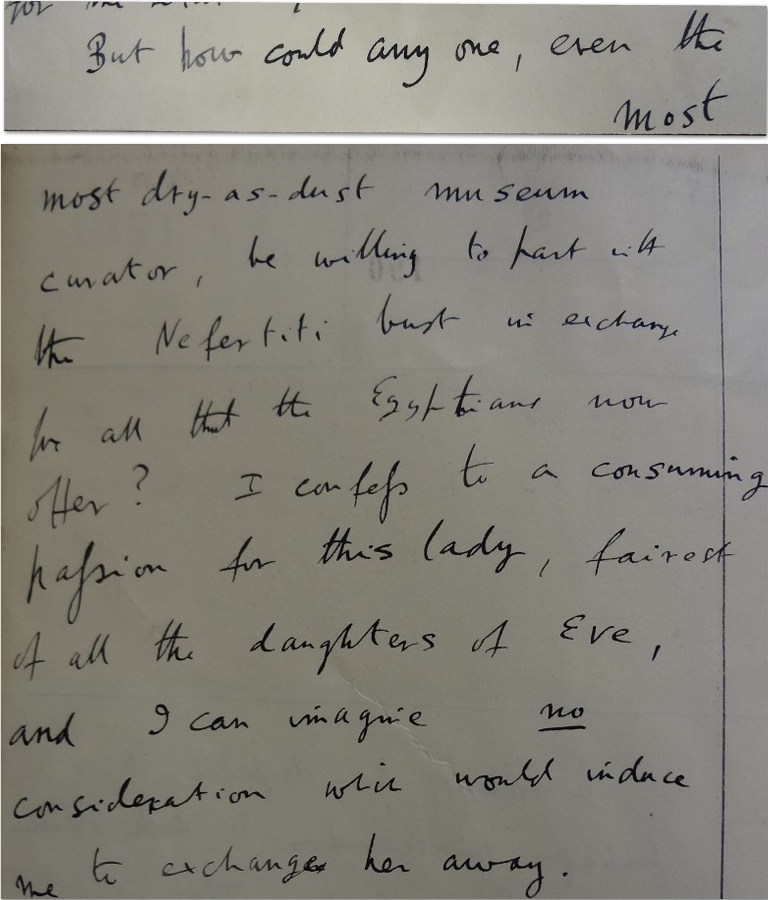

‘How could anyone, even the most dry-as-dust museum curator, be willing to part with the Nefertiti bust in exchange for all that the Egyptians now offer? I confess for a consuming passion for this lady, fairest of all the daughters of Eve, and I can imagine no consideration which would induce me to exchange her away.’ (FO 371/14647)

Gaselee’s minute, 22 April 1930 (catalogue reference: FO 371/14647)

The case was raised again after the Second World War. During the war, Nefertiti was removed to the Berlin zoo, along with other artefacts from the Museum. In 1945, it was transferred to a salt mine in Thuringia, where it was eventually found by the Americans in April, and transferred to their repository in Wiesbaden (FO 371/53375).

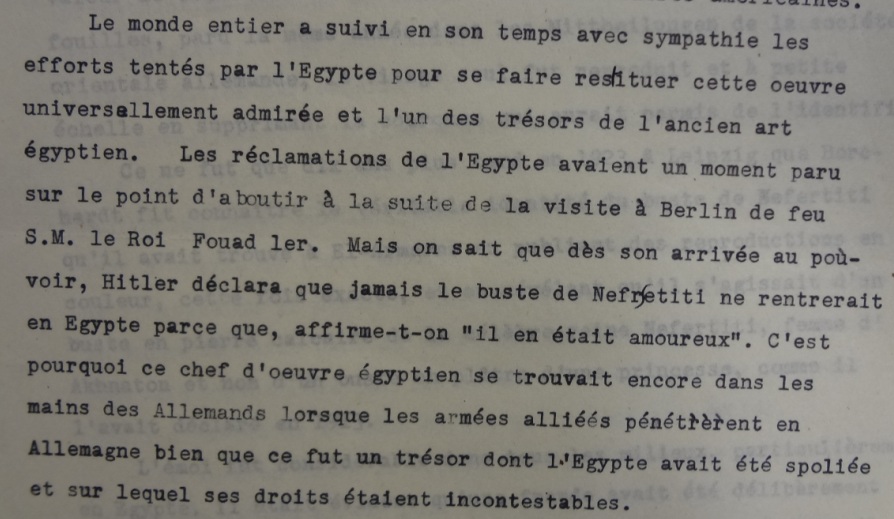

In May 1946, the Egyptian ambassador wrote to the Foreign Office. Forwarding a note the Egyptian Government had sent to the Allied Control Commission in Germany, he asked for support in order to get Nefertiti back. The note recalled the almost successful negotiations that had occurred during the King’s visit in 1929 and that it was a well-known fact that ‘when Hitler came to power, he stated that the bust of Nefertiti would never return to Egypt because, as it is affirmed, “he was in love with it”’. Now that Hitler had been defeated, the note continued, there was ‘no obstacle to putting an end to a spoliation based on fraud and maintained by force’ (FO 371/53375).

Note by the Egyptian Government, 14 April 1946 (catalogue reference: FO 371/53375)

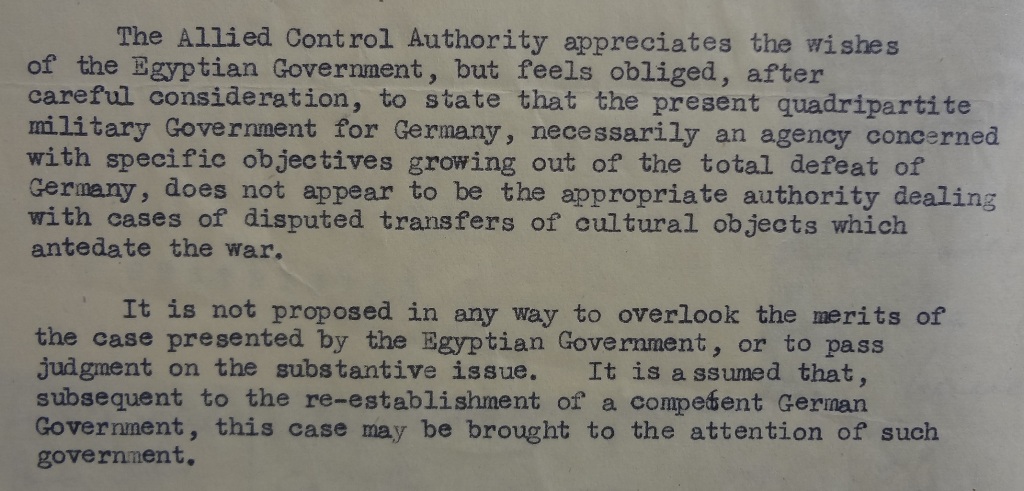

The Foreign Office explained that they couldn’t do anything as the bust had been discovered by the Americans, who felt Nefertiti was ‘in safe custody and at the present time (…) regarded as part of the cultural heritage of the world, located in Germany’ (FO 1057/273). The Allied Control Authority finally replied in December 1946 that restitutions could only be carried out in the case of objects which had been looted during the war. This didn’t apply to Nefertiti and the Egyptian government should therefore wait for the reestablishment of a German government (FO 371/63051).

The Allied Control Authority’s reply to the Egyptian Government, 14 December 1946 (catalogue reference: FO 371/63051)

“Replica” of the bust of Nefertit, Samalut, Egypt (image: Wikimedia Commons)

The Nefertiti affair is still ongoing and is an everlasting debate. What is not debatable is that Nefertiti, whose name means ‘the beautiful one has come’, is an iconic symbol of Egyptian cultural heritage and ancient and modern standards of beauty. So much so that when a rather unfortunate (truly hideous, actually) ‘replica’ of the bust was unveiled at the entrance of the city of Samalut, the people rebelled and forced the local authorities to take it down.

‘You cannot describe it with words, you must see it’, Borchardt wrote in his diary. He was right. Nefertiti returned to West Berlin in 1956, and has since then kept smiling her enigmatic smile (much more bewitching than Mona Lisa’s, if you were wondering). The Assistant Oriental Secretary put it more underwhelmingly in 1927, but he was right too – it is ‘a lovely thing’ (FO 141/440).

This goes straight to the heart of colonisation and archaeology where various countries (principally France, UK and Germany) have removed artefacts, even with official permission. The roles of all three countries in Africa, particularly in Egypt is not edifying, there was even a plan to smuggle the Dead Sea Scrolls out of Jordan in the late 1950s.

Analogy, in my view, it’s like going in someone else back garden and without permission excavating to find some treasures and calling it their own and keeping it. Morally and Ethically it seems wrong as its Egyptian’s history which should be enjoyed by the people of their country first and foremost.

I am tracingmy granfathers war medals seems nobody can help me he has 2 king George mesals 1 civilision medal 43135 Dublin royal irish fusiliers 6/r

Hi Padraig,

Thank you for your comment.

We’re unable to help with research requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

I hope that helps.

Nell

These comments miss the point that all these objects were taken with the full permission of the authorities at the time. It is wrong to apply the standards and laws of today to things that happened 90-200 years ago. Please don’t forget that Egypt still has by far and away the most fabulous collection of its antiquities anywhere–don’t give the impression that the country has been denuded of its heritage.

But why not have a 3D printed exact replica made?

At a press conference an Egyptian of high dignity made this comment about the bust: “She is our very best embassador, always at work for no salary. May she stay in Berlin and keep on working!”

[…] – Dr J. Desplat (2016) “The Nefertiti affair: The history of a repatriation debate” Available online at: http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/nefertiti-affair-history-repatriation-debate/ […]

I wish there was a body part to the head of nefartiti😍

I honestly think that it is outrageous that this is even an argument. I mean it was stolen and is being used for the sole purpose of generating tourist revenue in the museum. I would be open to hearing the other side of the argument in that Germany should not give it back because out of all my 7 years on earth I do not understand how someone could think that.

This is truly ridiculous. It encourages and teaches the German people that stealing is okay. What are they going to steal next from the less fortunate in Africa????? Crazy.