People queuing for hours, sometimes throughout the night, often to face closed doors. This wasn’t Russia during the First World War, but London in 1972. People were not queuing for bread, but for gold.

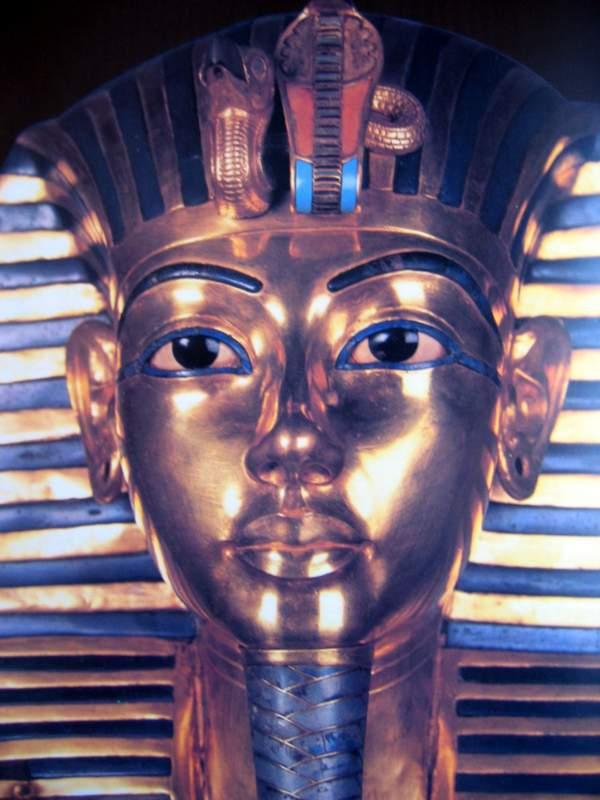

Tutankhamun’s gold mask (photograph: Juliette Desplat)

Some of you may remember the 1972 Tutankhamun exhibition held by the British Museum, the first ‘blockbuster’ exhibition in the UK. A miracle of museology, bringing together objects from the tomb of the boy king discovered virtually intact half a century before, it was also a masterpiece in terms of diplomacy and negotiations. And a logistical and security nightmare.

The possibility of a Tutankhamun exhibition at the British Museum was first raised in 1967, but the idea only really started to take shape in 1969, for an exhibition to start in the spring of 1972 (T 227/3204). The negotiations were described as ‘some splendid muddle’ by John Henniker, of the British Council; the general feeling was that too many people were involved too soon (FCO 39/570). Having waded through the files with a Civil Service List close at hand, I can only concur. Can you imagine ‘War and Peace’ transposed to a governmental setting? Right. You’re not even close.

The first draft of an inter-governmental agreement between the UK and Egypt (then known as the United Arab Republic) was circulated in the winter of 1969 but the negotiations dragged along and the opening date remained uncertain.

The first issue was money. Although everybody was very enthusiastic at the idea of such an exhibition, no government department was prepared to pay for it. In 1969, Lord Thomson of Fleet announced that Times Newspaper Ltd was prepared to sponsor the exhibition. The Committee appointed by the Trustees of the British Museum thought there was ‘historical justification for the association with the Times‘, but as exclusive rights had not gone down too well with Egyptian nationalists in 1922, it was agreed The Times would not demand exclusive coverage (FCO 39/570).

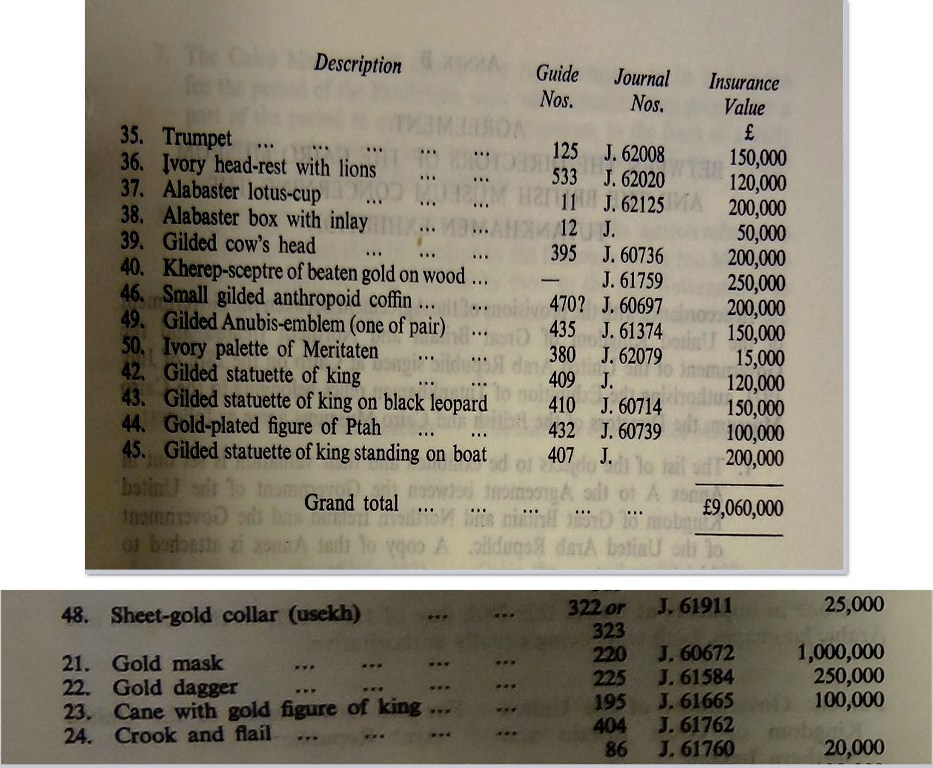

Then, there was the question of insurance. The artefacts were, of course, invaluable. They had to be priced all the same. On top of the usual insurance covering loss, damage and failure to return to Cairo, the UAR Ministry of Culture wanted to insure the antiquities against war risk, which the Treasury was not prepare to concede (T 227/3204).

In the end, after an evaluation conducted by experts from the British Museum and the Cairo Museum, Tutankhamun’s treasures were valued at £9,060,000; the gold mask alone had an insurance value of £1,000,000. The Egyptians also wanted to make sure the objects could not be the subject of a legal restraint in the British Courts on behalf of someone having a claim against the UAR Government. It was agreed that as the antiquities were the property of the Government, they would be protected by sovereign immunity (FCO 39/997). In the end, they were quite right to be cautious. Letters very soon began to arrive from people whose assets had been blocked in Egypt since the 1952 revolution. ‘I am delighted about Tutankhamun,’ one of them wrote on the opening day, ‘but I feel entitled to my share of the proceeds before they leave this country’ (FCO 39/1238).

Insurance value of the artefacts loaned to the British Museum (catalogue reference: FCO 39/997)

International relations and susceptibilities also had to be considered. The Department of Education and Science wondered whether the Israelis would be offended if the Queen opened the exhibition. The Foreign and

Commonwealth Office (FCO) didn’t think there was any need to worry and noted: ‘Tut has been dead a long time’ (FCO 39/998). Then, there was the obscure matter of the quality of the paper used by HM Embassy in Cairo. The Nationality and Treaty Department, complained bitterly (and repeatedly) about the flimsiness of Cairo’s paper: ‘why Cairo cannot type on the best paper when we specifically asked for it I don’t know’ (FCO 39/999).

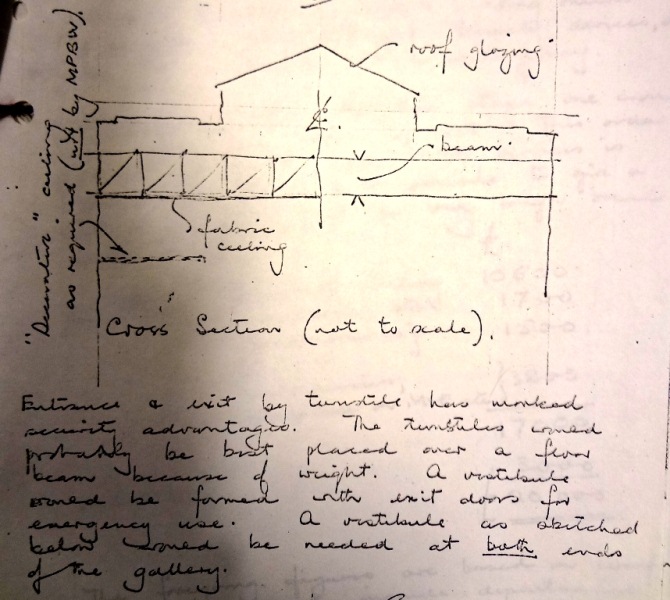

Sketch of the gallery (catalogue reference: FCO 39/570)

The exact location of the exhibition caused something of a problem as well. As it was quite clear the British Museum could not build a new gallery in time, it was decided to install Tutankhamun’s objects in the Ethnographical Gallery, on the upper floor. One of the main security concerns was the roof of the gallery, which had ‘a large glazed area and a lath and plaster ceiling’. It was agreed to erect a metal frame below, to brick up the windows on the inside, and to add bolts and turnstiles (FCO 39/570).

The travel arrangements for Tutankhamun’s treasures were also discussed at great length. In the summer of 1969, I. E. Edwards, the Keeper of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum, had approached the RAF and received a lukewarm response. ‘After all,’ the head of the FCO’s Cultural Department commented, ‘the last time the RAF were in Egypt, as far as I can recall, they were dropping bombs.’

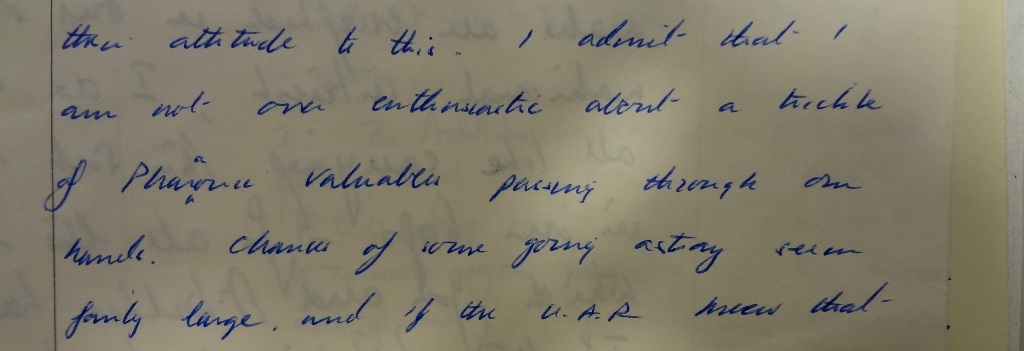

It was then suggested that diplomatic couriers and bags could be used for the transport of the lighter pieces. The FCO wasn’t too happy about it. J. Walker commented:

‘I am not over-enthusiastic about a trickle of Pharaonic valuables passing through our hands. Chances of some going astray seem fairly large.’

Cosmo Stewart, the Head of the Cultural Relations Department, concurred:

‘from the way I have seen FCO bags handled I should be reluctant to commit anything very fragile to them, however well packed!’ (FCO 39/570).

Minute by J. Walker, 08/12/1972 (catalogue reference: FCO 39/570)

It was finally agreed that some of the most precious objects, including the gold mask, would be carried by the RAF, the others by two special charter flights provided by BOAC (FCO 39/998).

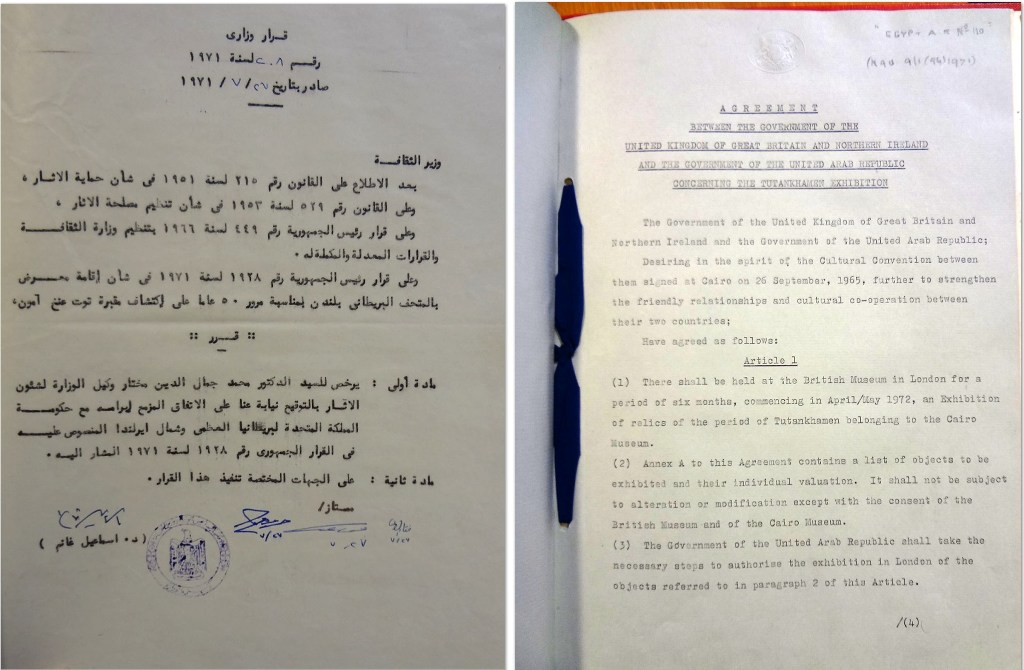

The ministerial decree authorizing the signing of the agreement was signed on 27 July 1971, and the international agreement itself on the following day (FO 93/32/110).

Ministerial decree of 27 July 1971 and inter-governmental agreement of 28 July 1971 (catalogue reference: FO 93/32/110)

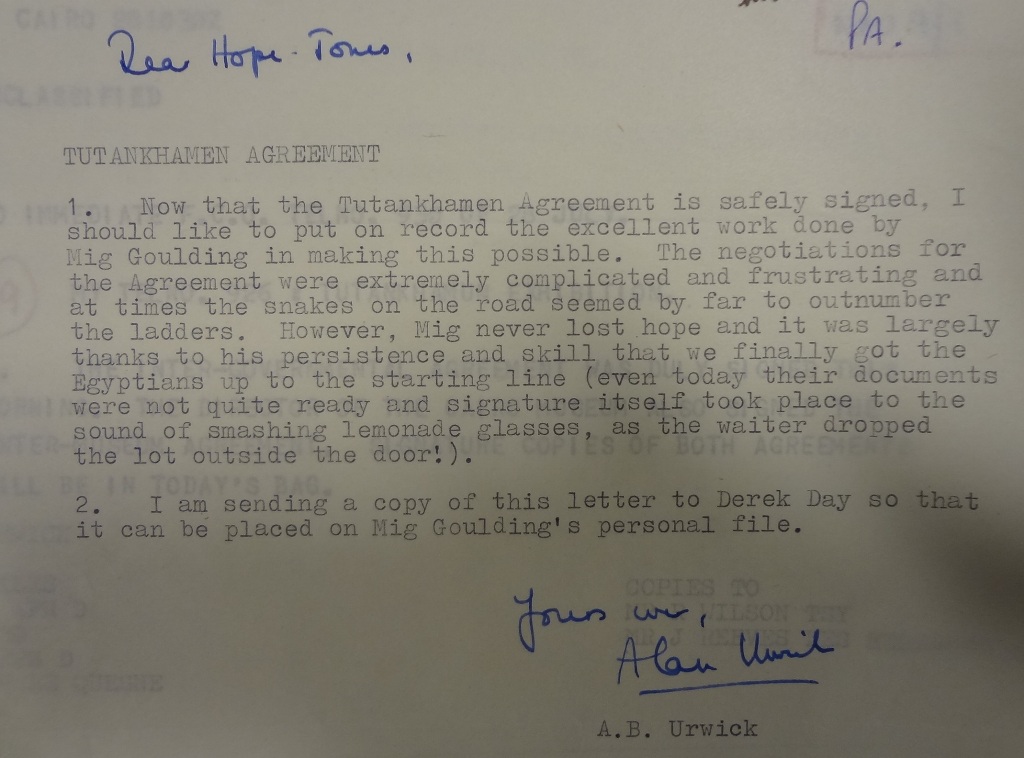

In the words of Holding, from the North African Department of the FCO, it had been ‘something of a cliff-hanger’ and the Counsellor at the British Embassy in Cairo reported that the signature had taken place ‘to the sound of smashing lemonade glasses as the waiter dropped the lot outside the door!’ (FCO 39/998).

Urwick to Hope-Jones, 28/07/1971 (catalogue reference: FCO 39/998)

‘Treasures of Tutankhamun’ was finally opened by the Queen on 29 March 1972 and was scheduled to run for six months, until 30 September (FCO 39/1238). Open seven days a week, the exhibition attracted close to 1,700,000 visitors paying 50p each (25p for students, children and pensioners) to gaze into the eyes of Pharaoh (FCO 39/1240). As early as September 1971, Edwards had warned that ‘the biggest difficulty [would] be organising the crowds’ (FCO 39/998). He was absolutely right: the crowds were overwhelming. People were queuing in the gallery on the first floor, down the stairs, around the forecourt and even on the pavement. On 5 July, the Egyptian Gazette reported:

‘King Tut’s fans, as the Tutankhamen enthusiasts were called, sometimes kept all-night vigils near the British Museum (…), they did this to make sure to get a ticket to the show on the following day’ (FCO 39/1239).

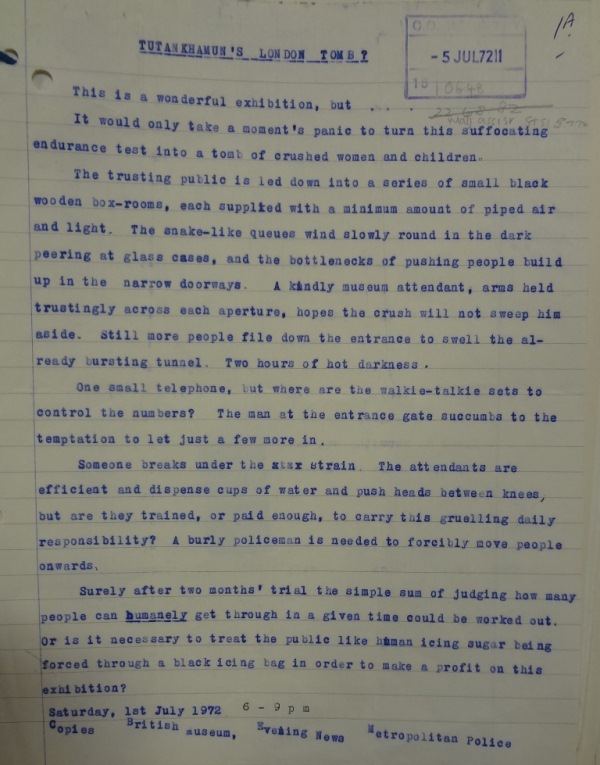

In order to meet the great and incredibly steady public demand, the Egyptian government agreed to an extension of the exhibition until 31 December (FCO 39/1239). You can never please everybody, though. The Metropolitan Police received an anonymous letter, dated 1 July 1972, complaining of conditions imposed on the people visiting the exhibition. ‘The snake-like queues,’ the disgruntled customer wrote, ‘wind slowly round in the dark peering at glass cases, and the bottleneck of pushing people builds up in the narrow doorways’ (MEPO 26/3).

Anonymous letter sent to the Police, 01/07/1972 (catalogue reference: MEPO 26/3)

People might have been doing a bit of pushing around, but it was all for a good cause. First, the exhibition actually boosted the tourist trade in Egypt. As early as April 1972, the Egyptian Tourist Information Centre registered an increase in tourism and attributed it to ‘Treasures of Tutankhamun’ (FCO 39/1238). More importantly, all the proceeds were paid to the UNESCO fund for the rescue of the temples of Philae, the ‘Pearl of Egypt’, threatened with flooding with the waters of the Aswan Dam. On 2 May 1972, a £600,000 cheque was handed to UNESCO’s Director General for the Campaign; a further sum (£57,731) was added when the accounts were completed (OD 24/149).

Philae during the Second World War (catalogue reference OS 1/384)

Just like in the 1920s, a wave of frantic Tutmania swept over the UK. Replica jewellery, cards, stamps, scarves, posters, carrier bags… Tutankhamun, with his ‘trickle of Pharaonic valuables’, was everywhere, achieving the great Egyptian aim of eternal fame, and probably very smugly quoting the Book of the Dead to himself: ‘I shall not die again’!

The reason why Treasury would not insure the exhibits is that Government does not insure but indemnifies as insurance supposes that you can replace the items. The British Museum itself is covered by the indemnity provisions and it was in the 1950s that it was pointed out by a Treasury official that you cannot replace like for like what might be lost.

[…] ‘A trickle of Pharaonic valuables’ […]