‘I came here in 1948 my husband sent for me. He and his brother came up a year before…it was a lovely day, beautiful, and they were all at the dock waiting for me. I think it was Tilbury, I was very excited.’

BBC History, ‘Windrush – Arrivals’ (accessed 5 April 2023)

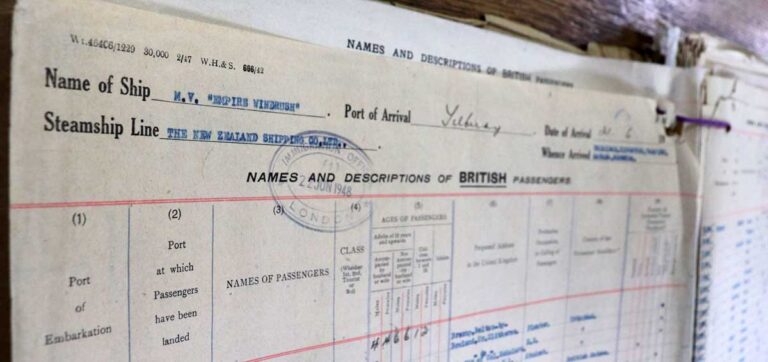

These are the words of Lucilda Harris, a passenger on board the Empire Windrush, describing the ship’s arrival at Tilbury Docks in June 1948. Lucilda was a 31-year-old dressmaker from Jamaica and was joining her husband, who had migrated to Britain with his brother the year before.

The stories of the women on board the Empire Windrush are often not discussed in detail, most likely because they were in the minority. Louise Ryan and Wendy Webster state that mainstream theories of migration tend to focus on the male economic migrant. As a result, they tend ‘to exacerbate the exclusion of women from analysis of migration’ (see footnote 1). Nonetheless, they do acknowledge that there has ‘been a growing call for a gendered approach to migration’ which includes both men and women (see footnote 1). Of the 1,027 passengers on board, just over 300 were women (see footnote 2). Studying their migration stories offers a more nuanced understanding of the Empire Windrush and post-war migration more broadly.

This blog offers case studies that highlight the diverse range of women who travelled on the ship. Where possible, it also explores their lives after they disembarked at Tilbury.

The iconic Empire Windrush passenger list acts as gateway into the personal migration stories of these individuals. It is an invaluable source as it contains a wealth of information about passengers – and their lives beyond the journey itself – all in one place. It represents individual and collective narratives of excitement, challenges and new opportunities.

However, researching the stories of migrant women at The National Archives can be challenging, as it can be hard to find their voices. Even when records do survive, they are largely official documents produced by government departments. As a result, they rarely provide us with information on people’s lived experiences, written in their own words.

Migrating to Britain

Passengers travelled to Britain for a variety of reasons. Some migrated to Britain to seek new opportunities and economic stability, others were joining family and friends like Lucilda. The extraction of resources from the Caribbean by the British contributed to the poor economic situation in the Caribbean, which influenced post-war migration to Britain.

Whilst some of the case studies in this blog explore why these women migrated to Britain, this is not always possible due to gaps in what has historically been recorded. For some women, the only information we have about their lives is their entry in the passenger list, highlighting the ongoing challenges of researching women’s stories.

The women on board the Empire Windrush ranged in age from just 6 months to 80 years old. Passengers were largely migrating from islands in the Caribbean, including Trinidad, St Lucia, Grenada, Barbados and Jamaica. For example, 30-year-old Audrey Hickson gave her last country of residence as St Lucia. It seems she was heading to London as her onwards address was located in Marylebone.

However, this was not the case for everyone. A small number of passengers listed their last country of residence as somewhere in Britain, or another European country, and were returning from holidays or travels abroad. Writer, political activist and heiress Nancy Cunard was returning to Britain after her travels, and listed her last country of residence as France.

Travelling in different capacities

Some women travelled on the Empire Windrush alone, but were meeting family in Britain. As I mentioned earlier, Lucilda was re-uniting with her husband. Once he had saved up enough money to pay for her journey, she joined him in London (see footnote 3). Describing the journey, Lucilda recalled:

‘The journey took 22 days, and that was a very long time. We enjoyed the journey, I was coming up to meet my husband, I was very anxious to come and meet him, because when he left we were just married, we got married and he left the following day. Imagine how exciting it was for me.’

BBC History, ‘Windrush – Arrivals’ (accessed 5 April 2023)

Lucilda’s onwards address was listed in north London, not far from King’s Cross. She eventually settled with her husband in Brixton and the couple had five children. Both Lucilda and her husband supported other migrants who arrived in Brixton, and played a part in community life (see footnote 3).

It seems that 80-year-old Gertrude Whitelaw travelled alone and may have been on holiday. Her last country of residence was recorded as Scotland and her onwards address was listed as the Scottish village of Polmont in Stirlingshire, suggesting that she was returning home after her travels.

Other women on board travelled with their families. Doreen Zayne, aged 22, travelled with her husband Herbert Zayne and their two young children. Herbert was born in Jamaica and joined the Royal Airforce (RAF) during the Second World War, and Doreen was from Lancashire and served in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force. During this time, they met at Elmdon Airport close to Birmingham (see footnote 4). They later married and had two children.

After the war the family lived in Jamaica, but they returned to Britain on the Empire Windrush as Herbert struggled to find work (see footnote 5). The passenger list shows that Doreen and their two children travelled in class ‘A’ whilst Herbert travelled in class ‘C’, most likely to save money, as it was much cheaper. It also records their onwards address as Blackpool, where Doreen was born.

The Birmingham Daily Gazette wrote an article on the couple’s story and reported that Herbert hoped to find employment in Blackpool (see footnote 6). Interracial couples often experienced discrimination, in addition to hostility from family members. This was especially seen in mixed-race relationships between men of colour and white women (see footnote 7).

Occupations

The women on board were employed in various roles, including as dressmakers, typists, hairdressers, beauticians, nurses and bank clerks. 36-year-old Ann Green’s occupation was listed as ‘Beautician’. Her onwards address was recorded as Maltby in South Yorkshire and her last country of residence was noted as Bermuda.

Three women, Leila Kerr-Pearse, Nancy Laird, and Tyler Emily, even listed their occupations as ‘spinsters’, highlighting the perceived importance of a woman’s marital status at the time.

21-year-old Mona Baptiste from Trinidad listed her occupation as ‘Clerk’ on the passenger list. However, Mona was already an established blues singer at this point. A record from the Colonial Office provides more information on her career. It notes that ‘Miss Mona Baptiste, a “blues singer” from Trinidad, who was in the contingent on the “Empire Windrush”, appeared recently as a guest artiste in “Band Parade”, a popular BBC variety feature program’ (see footnote 8).

Mona went on to have a successful career in both the music and broadcasting industries. She was famously pictured at Tilbury with a saxophone and a group of RAF servicemen. One of Mona’s songs, Calypso Blues, features in The National Archives’ Windrush 75 Playlist.

Seven of the passengers (six women and one man) listed their occupation as ‘Nurse’ and likely went on to work for the newly established National Health Service. 35-year-old Jamaican nurse Ena Clare Sullivan listed her proposed onwards address as West Middlesex Hospital, where she undertook her nursing training.

However, the most common occupation was listed as ‘HD’, which stood for household domestic. There is no key to state the exact definition for this, but it would likely have referred to women looking after the home, although for a small number it may have entailed working as a cleaner in an external household.

57-year-old Elma Clarke travelled with her 30-year-old son, Ellis Clarke. Her occupation is listed as ‘HD’, and his as ‘barrister’. Their last country of residence was listed as Trinidad and both gave the same onward address in Chelsea, London.

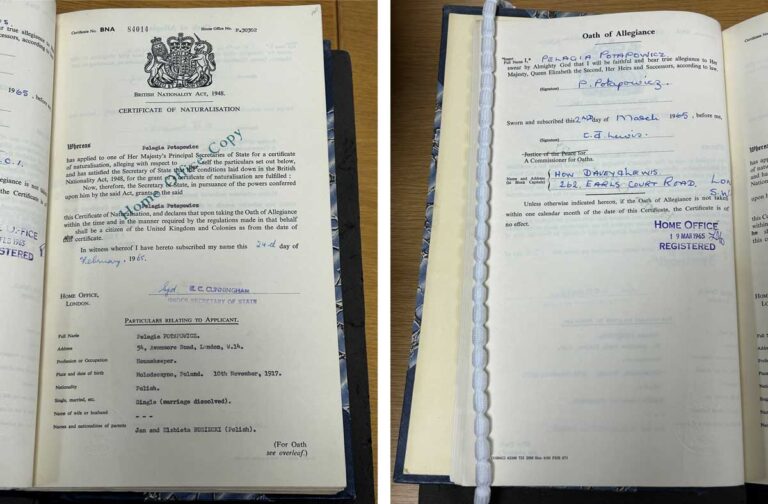

Similarly, Pelagai Potapowicz’s occupation was also recorded as ‘HD’, and her onwards address was in Plymouth. Pelagai and her daughter were two of the 66 Polish refugees that joined the ship in Tampico, Mexico. Displaced by the Second World War, they were able to travel to Britain as a result of the 1947 Polish Resettlement Act. The refugees were all women and children, and travelled in class ‘A’.

In 1965, Pelagai registered her British nationality, which shows that she went on to live in London, she was single (her marriage had been dissolved), and her occupation was listed as ‘Housekeeper’.

Researching the women on board the Empire Windrush reveals lesser-known migration stories and offers new insights into this symbolic moment. Whilst tracing the lives of migrant women in the archive can be difficult, it is possible to piece together some of their stories. The various case studies explored in this blog represent a snapshot into the lives of women who migrated to Britain, but there are still many stories waiting to be discovered.

Footnotes

- Louise Ryan and Wendy Webster, ‘Introduction’ in Gendering Migration: Masculinity, Femininity and Ethnicity in Post-war Britain by Louise Ryan and Wendy Webster (eds.), pp. 1-18, p. 5.

- This figure includes both women and girls.

- Windrush Foundation, ‘Pioneers: Lucilda Harris’, https://windrushfoundation.com/pioneers/lucilda-harris/ (accessed 4 April 2023).

- ‘They Met at Elmdon’, Birmingham Daily Gazette, 23 June 1948, p. 3.

- ‘Three Wives Back From Jamaica’, Daily Mirror, 23 June 1948, p. 8.

- ‘They Met at Elmdon’, Birmingham Daily Gazette, 23 June 1948, p. 3.

- For more information, see Anna Maguire, ‘‘You wouldn’t want your daughter marrying one’: parental intervention into mixed-race relationships in post-war Britain’, Historical Research, 92 (2019), pp 432-444.

- CO 876/88, The National Archives.

Is there more personal information on Mona Baptiste? She looks like a striking woman at the age of twenty-one, and the RAF men look more than delighted to be entertained by her. What sort of information exists in the files mentioned in Footnote #8, please? Thank you.

Thanks for your comment and for your interest in Mona Baptiste. Unfortunately there is only a sentence about her work in the reference mentioned in footnote 8, but you can find more information about her on the Irish Emigration Museum’s website.

I am the co-author of Mona Baptiste’s biography; What About the Princess? – The Life and Times of Mona Baptiste. She was in fact 22 when she disembarked from the Windrush (it had been her 22nd birthday the previous day). She never played the saxophone in her life, it was just a prop for the photograph at Tilbury! I have visited her family in Trinidad and am in close contact with her second husband and her son. I’m always happy to talk to anyone about Mona, she was a remarkable woman.

Thanks very much for your comment. We have taken Mona’s age as 21 since that was how it was recorded on the passenger list. Thank you for sharing that she had her birthday whilst on the ship. We have also amended the text to say ‘a saxophone’ instead of ‘her saxophone’, to avoid the impression that she would have actually played it!

Gertrude Whitelaw quoted in the article above was in fact the grandmother of Willie Whitelaw who went on to become Home Secretary in Margaret Thatcher’s Government. For many years he was effectively Deputy Prime Minister to Thatcher. Gertrude died in November 1948, less than four months after returning to Britain.

This blog previously referenced Elma Clarke’s nationality certificate, which suggests: Elma was born in Musserabad, India; was living in Walthamstow, London; and may have had Indo-Caribbean heritage. We have now removed this as the writer believes more research is needed to confirm the certificate is Elma’s.

An interesting additional piece of information about Elma Clarke is that her son Ellis, with whom she travelled on the Windrush, later became the first ever President of Trinidad and Tobago. He was knighted in 1972. Elma died, aged 93, in 1994.