A plethora of information exists in our collections on Poland and the plight of Polish refugees. Whichever series you choose to research, there is likely to be a reference to Poland’s turbulent history and the suffering of its people during the years covering the Second World War and beyond.

After the German and Russian invasions of Poland in September 1939, the Polish Government and many Polish soldiers, airmen and sailors escaped first to France and then to Britain, joining the Allies in the defence of the British Isles.

Stalin’s programme of ethnic cleansing in Eastern Poland began on 10 February 1940 and continued into 1941. Soviet statistics claim that nearly 280,000 families were uprooted from their homes, loaded into cattle trucks and taken to prisons and forced labour camps in Russia, but other sources claim that the numbers could be as high as two million.

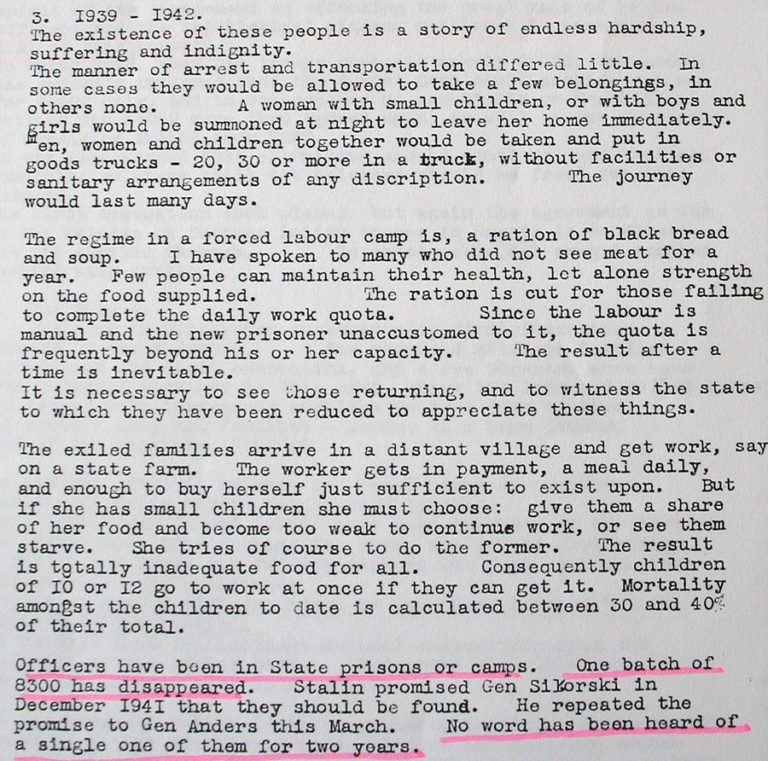

Lieutenant Major Hulls, British Liaison Officer to the Polish commander General Anders, described the deportations of families to Siberia during Stalin’s ethnic cleansing of Eastern Poland. His report also questioned the disappearance on Soviet soil of Polish officers and intelligentsia, whose remains were discovered a year later by the Nazis in a series of mass graves[ref]WO 208 1753. Leslie Hull’s report from Yangi Yul in Uzbekistan, HQ of the newly formed Polish II Corps.[/ref].

Upon the signing of the Sikorski-Mayski Pact of July 1941, those soldiers who survived imprisonment were released and could join the newly formed Polish II Corps, which later fought in major Allied campaigns in North Africa, the Middle East and Italy. The soldiers and their families were required to find their own way to the nearest staging posts. From there they were directed to assembly points across Russia and Kazakhstan and evacuated in convoys to the port of Krasnovodsk. There they boarded tankers to cross the Caspian Sea to the transit camps in Pahlevi, before being moved to temporary camps in Tehran where they were segregated[ref]WO 204 8711. Report on Pahlevi Refugee Camp.[/ref].

The soldiers were almost immediately sent from Iran to Iraq to join the Allied forces under British command. The Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare of the Polish government-in-exile in London organised where family groups were to be sent. These exiled families continued their refugee journeys, ending up in India, Africa, and other British colonies and protectorates. It is estimated that only around 119,000 Poles were evacuated, leaving the majority behind in Russia with no hope of rescue.

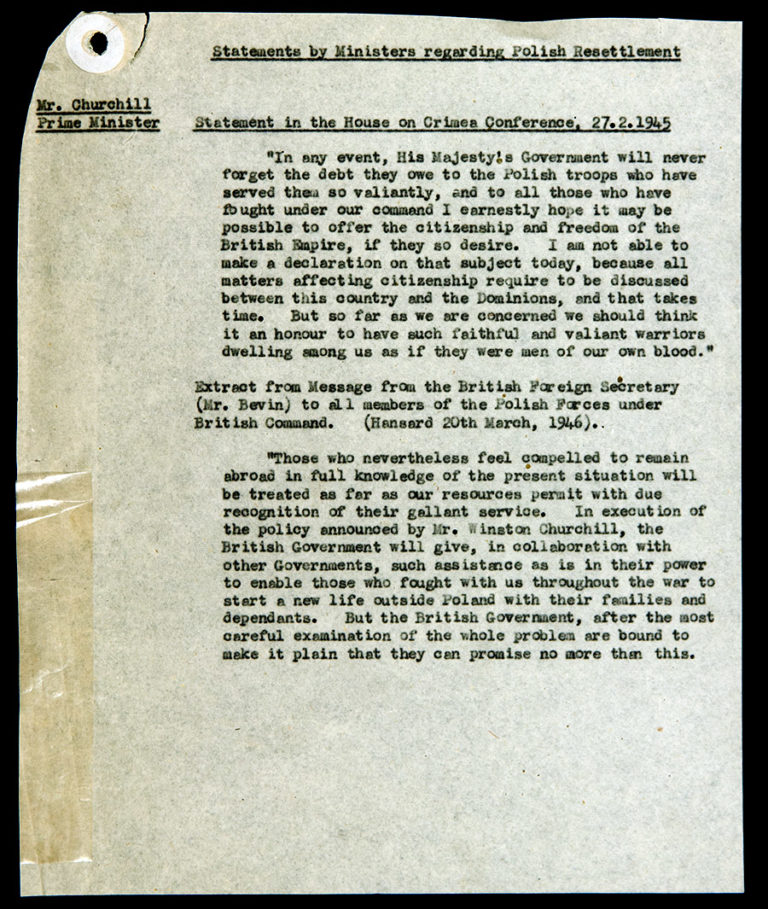

It is commonly accepted that the Poles were looked upon favourably during the war by the British; certainly the bravery of the Polish pilots and the land forces was acknowledged. But post-war attitudes of some groups were not all welcoming. Towards the end of the war, British policy towards Poland had changed quite drastically and no assurances about the future of Polish forces were in place. Churchill’s vision for the Polish troops was quite clear, as he stated at the Crimea Conference of February 1945. The British Foreign Secretary’s statement remained ambiguous[ref]AST 18 1. Statements in the House of Commons regarding Polish resettlement.[/ref].

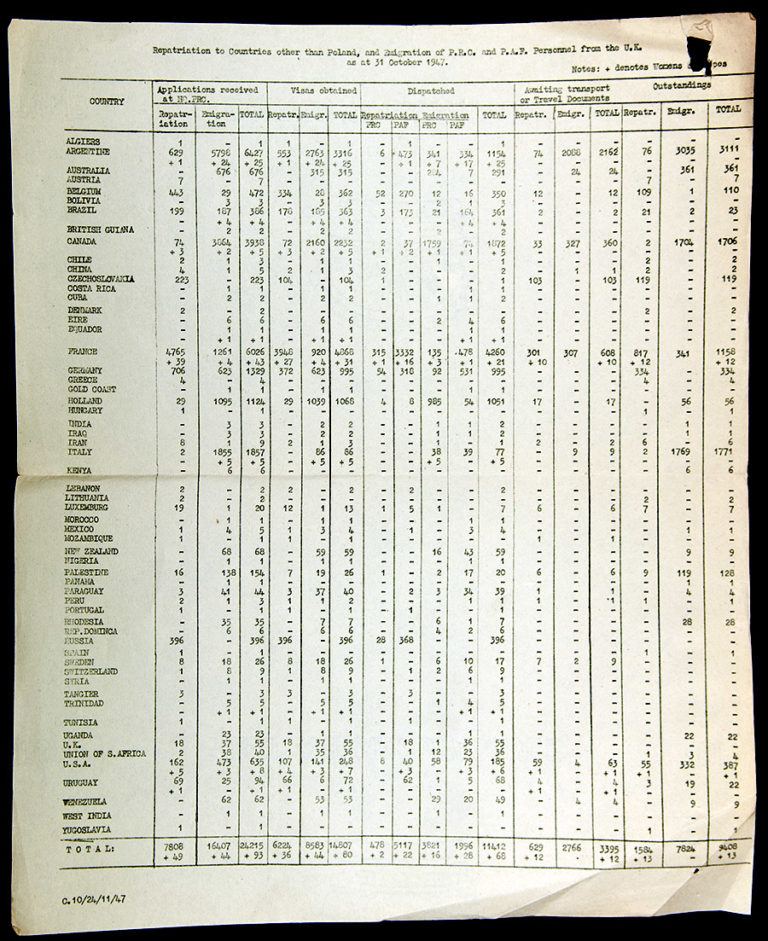

After the Second World War, the majority of Polish troops who fought alongside the British were unable to return to Poland. On May 22 1946, Anthony Bevan announced that the Polish Resettlement Corps was to be formed as a body of the British Army, enabling Poles who had fought under British command to join. The aim was to have all members demobilised within two years. The Polish Resettlement Bill was drawn up in 1946 and the Act was passed in 1947. It was the first ever mass immigration legislation passed by Parliament in Britain and allowed more than 220,000 Poles to remain in the United Kingdom. Around half chose to emigrate or were repatriated[ref]WO 315 16. Table showing repatriation and emigration of Polish Resettlement Corps and Polish Air Force personnel as at October 1947.[/ref].

His Majesty’s government gave its approval for the War Office to make arrangements to bring to the United Kingdom the soldiers’ immediate relatives and dependants. These not only included the families scattered around British colonies and protectorates, but also those families who made it through to the British Zone in Germany following the liberation of the Nazi camps.

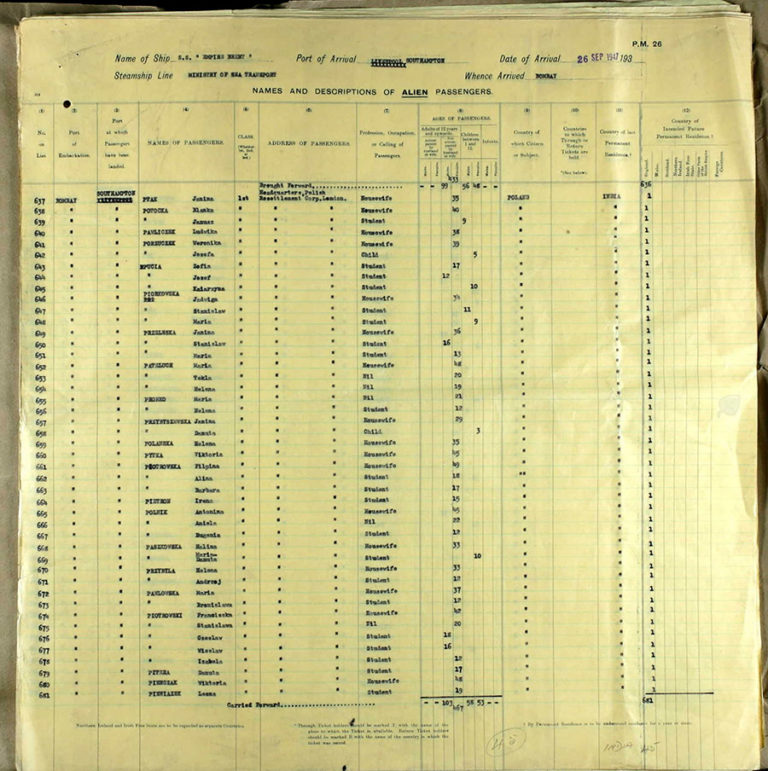

In July 1947, the Assistance Board took over the welfare of some 10-12,000 people who arrived on ships before the end of 1948[ref]BT 26 1230. Passenger list of arrivals from Bombay, 26 September 1947.[/ref]. These families had no knowledge of English and special schools were established for the children, so they could learn the language and culture of their newly adopted country. By 1950 these schools followed the English curriculum and instruction was in English. The Polish youth were quick to absorb the language and adopt their new way of life.

However, the government still had to persuade the British public that the Poles were an asset. Assimilation was not easy as English was still a second language to most and, although attending language courses was encouraged, communities would still speak in their native tongues, thereby slowing down the process of integration.

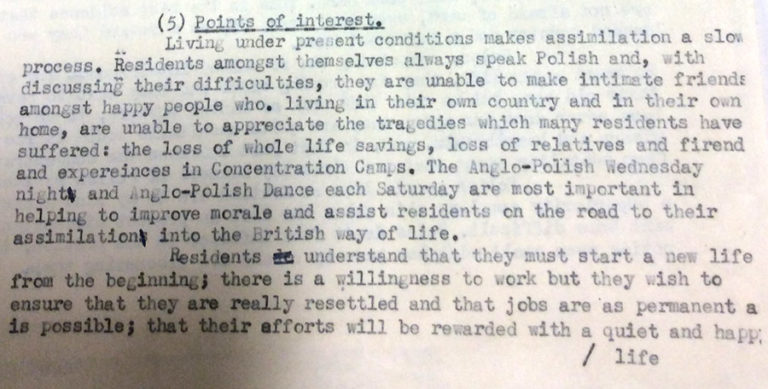

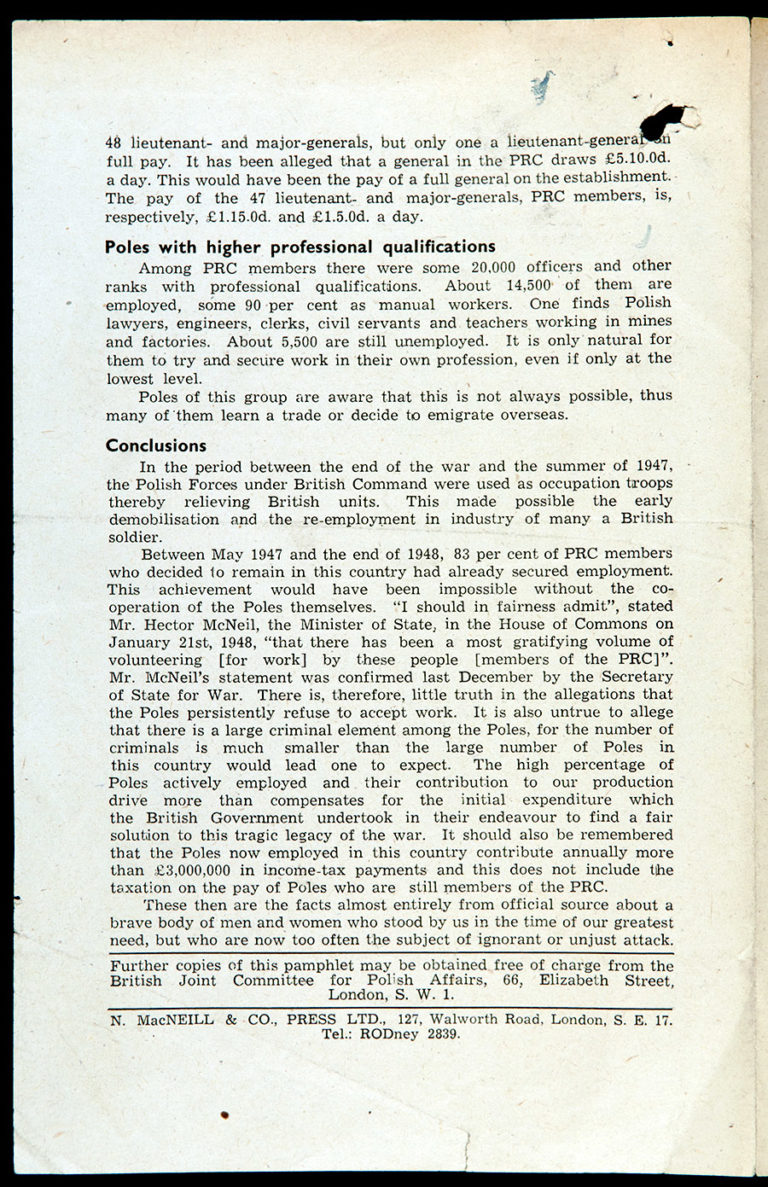

Attitudes of prejudice and distrust of the receiving community were associated with factors of a political, economic and emotional nature[ref]AST 7 1456. A warden’s report to the National Assistance Board Annual Report 1947.[/ref]. Shortages of housing and rations fuelled negative public opinion, which was in turn influenced by government, press and, in particular, the trade unions. This led to a campaign, launched by The British Joint Committee for Polish Affairs, to inform the British public of the benefits of the Polish immigrants and also to remind them of the vital role they played as Allies[ref]AST 18 1. Leaflet ‘Do the Poles here really work?’ Published by MacNEILL & Co PRESS Ltd on behalf of the British Joint Committee for Polish Affairs.[/ref].

The Polish Resettlement Corps was disbanded in 1949. During its short-lived existence, it brought about the reunion of families and the integration of displaced Poles into British society. For those Polish soldiers, airmen and sailors who fought with the Allies, it must have been welcome news when the British government allowed them to remain in the United Kingdom with their families, who had endured years of statelessness across the globe.

On the Record: Refugee Stories available now

To mark Refugee Week we have made a bonus episode of our podcast On the Record at The National Archives, which is now available on the Archives Media Player and on podcast listening apps.

Subscribe: iTunes | Spotify | RadioPublic | Google Podcasts

You can also catch up on previous series in which have uncovered the true stories of famous spies and looked at protest – from the medieval Peasants’ Revolt to Black power in the courtroom. Most recently we have read famous love letters, and between the lines of less obviously romantic records, to discover the love stories of everyday people from the last 500 years.

PLEASE NOTE: Due to the age of this blog, no new comments will be published on it. To ask questions relating to family history or historical research, please use our live chat or online form. We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.

and the wave after wave of the same people who were brought up through Africa, into Europe and onto Britain, in the early fifties, my father was a skilled metal worker and eventually settled for the rest of his life at the Pressed Steel Fisher plant in Swindon ( later British Leyland , now BMW Mini). There is still probably more material out there, but they are dying off now sadly, good luck.

There was a large Polish community near Newton Abbot in Devon, where there was a resettlement centre, and a number of them are buried in the cemetery at Newton Abbot. Unfortunately the miners unions didn’t like the Polish miners as they thought they were taking British jobs at a time (1940s/1950s) when the British Government wanted to export more British coal to bolster the UK economy.

Well done Ela! for taking on a long-lost history of Poles who were Allys in war and eventually became refugees, who contributed so much to the society of their adopted country.

Nice summary Ella! You and I I’m sure have told this story (which is family history to us) to many of our friends and it never ceases to amaze me that the majority of the public have no idea why so many Poles ended up in the UK after WW2. It’s a history that deserves to be more widely known!

Thank You Ela for this very brief snapshot of some of the many many Documents in The National Archives detailing the contribution of Poles to the War effort and post-War. Whether it be the contribution of Polish [and French] Mathematicians to cracking The Enigma Code, Polish Army in Britain, the various Campaigns in the Desert, Monte Cassino, and Arnhem, and D-Day Landings, Airmen in the RAF, Poles in the French Army in Narvik and those who remained in Occupied France and fought in various organisations like NUMRI and the French Resistance, many of whom escaped across the Pyrenees, SOE and Cichociemni [the precursors to GROM] and Audley End – Poles have contributed in so many ways, it was heartbreaking that Post-War, those who served were denied the right to take their rightful place in the 1946 VE Day celebrations so as not to “upset” Stalin, and discrimination against those Poles who settled in the UK was widespread even within some Trade Unions. Many Poles fought to expose the truth about Katyn and were not listened to or believed with the truth officially suppressed, thankfully, they have now been vindicted by history. For many, the betrayal and bitterness of Yalta pervaded the consciousness of many deprived of returning to their Homeland, those who did so were sent to the Gulags or treated as spies and traitors, shot, disappeared, imprisoned or featured in “show trials” …. then executed. The National Archives contains a wealth of documents and information – many stories yet to be told – if only someone has the time to sit and search that vast Archive and tell those stories that deserve to be told and see the light of day.

Well done Ela

I found your piece very moving and your mothers comments regarding nationality resonated very strongly with me.

My Grandfather was definitely an asset. When Russian troops invaded they gave the Tomaniaks one hour to pack what they could and leave their farm. My Grandfather Vaslow Tomaniak and his brother Tadik (unsure of correct spelling) ran away, and though underage, lied their way into fighting with the British army in Siberia and North Africa. Somewhere along the way Vaslow(?) met my English Grandmother who was driving wagons for the British army (what amazing people). After the war my Grandfather married Molly Whalley and they settled in England. My Grandad worked until retirement and when he passed away (having survived my Grandmother) he left the house he had paid for to his children. He was an inspiration and was loved and respected by all who knew him and I just wanted to share his story.

Mr Ralphson

I guess Vaslow is Wacław

Tadik is actually diminutive of Tadeusz (Thaddeus) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thaddeus

Regards

Do take the time to listen to 90 year old Wojtek Narębski on the TEDxKazimierz in 2015

“A life well lived | Wojciech Narębski | https://youtu.be/WR2kKw3kQEA ”

or Krysia telling her war time experiences

https://projectkazimierz.com/krysia-griffith-jones Invasion, Flight, Arrest, Imprisonment, Release and Fighting Back ”

and here

https://projectkazimierz.com/krysia-griffith-jones-part-2 Release from Soviet Gulag and Service in the Anders Army

This is a query, really, though all the excerpts above are very moving., I well remember the indoor market in Nottingham in the late 1950s which was run by Polish people, and you could get stuff there that wasn’t available anywhere else. My query is, how many Polish people came by what route to settle in Britain? For example, I’ve remade that the Polish cabinet escaped into Romania, with which there was then a common frontier. And then what? And having destroyed the country of Poland, did Polish refugees simply wander through southern Germany into France, and then via the Channel into England?

Thank you for any information you may be able to provide on this matter.

Tim Marshall

Thankyou Mr. Ralphson, it’s wonderful to hear this story.

See recently published book, From The Soviet Gulag To Arnhem, a story of a Polish paratrooper in WW2. Written by Nicholas Kinloch about his grandfather.

Hello

Ala from Swindon

This is the history of my family

Yes, Tadek is short for Tadeusz

And Wacław is correct

To answer Tim Marshall;

The Poles came by boat to U.K. from the various British colonies they had been sent to and I know one route was to Australia. Unmarried women with children were sent there. People later emigrated.

How the soldiers in German prisoner of war camps and concentration camps made it out, I don’t know. Probably under their own steam

Not sure where to start. My Polish Father, at age 13, escaped from a German forced Labour train from Warsaw.

At some point, he joined the army and some years later, ended up helping the US army as a Gaurd. When the war finished he was in a German work scheme as a displaced person. After some years he then moved to the UK, as a displaced person. Sadly he passed away when I was 14. He didn’t like talking about his life after he was taken from his home. I have tried to piece together the path my father took but know only the briefest of details. I have photographs of him in Polish uniform and American Gaurds. Can someone guide me to what organisation or person that could help me? Dad couldn’t return to Poland so I feel he might of missed out on possible appreciation he may have been due. He used his brothers name so as to change his age and all or any records would be in that Christian name. Any guidance would be appreciated.

Hi Ela,

I’m currently writing a historical fiction novel about my grandad’s journey from Zakopane to Sheffield, UK, and this has been a great resource.

Thank you,

Steve

My Polish uncle came to this country after the war from Italy. He was in a Polish Resettlement Camp initially at Hounslow.

From there he ended up at Seething, Norfolk on a former USAAF bomber base. I believe he was there because the camp housed internees with origins of the Russian sector. I have tried approaching the museum at Seething about this with no success.

PLEASE NOTE: Due to the age of this blog, no new comments will be published on it. To ask questions relating to family history or historical research, please use our live chat or online form. We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.