The Court of Charles I

The execution of Charles I on 30 January 1649 still arouses strong emotions in many people. Controversial during his lifetime, the king was both vilified and exculpated in the immediate years after his execution, and he remains a source of significant debate among scholars, students and the general public alike.

His public trial at Westminster, for crimes of treason against his own subjects, and his public execution outside the Banqueting House in Whitehall are among the defining moments of early modern British history. By any standards, these moments were shocking for many across the Stuart dominions and beyond. Nor is it surprising that generations of historians have drawn upon the dramatic events of the trial, while in recent years plays and television dramas have reinterpreted the trial for new audiences.

Central to our understanding of these events are the recorded proceedings of the trial, which are held here at The National Archives. But what is the history of these records and why were they written?

‘Narrative of the Proceedings’

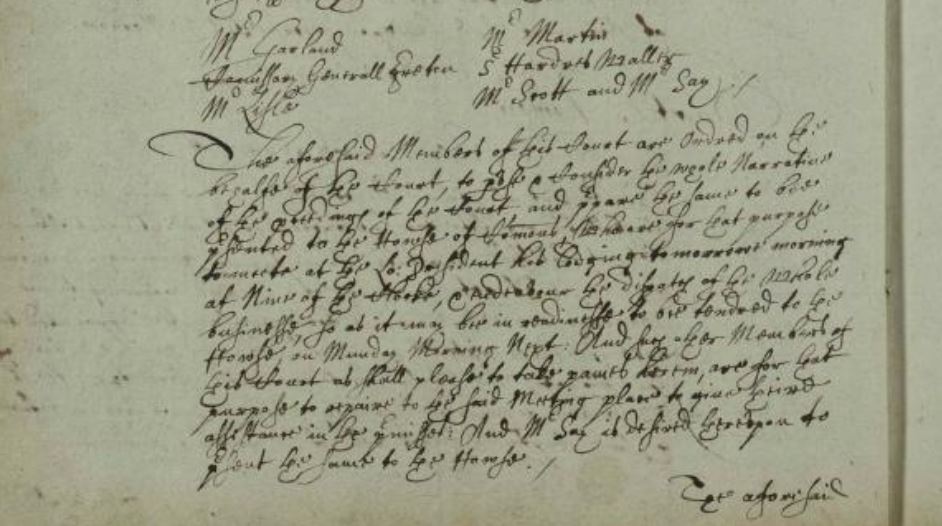

At the conclusion of the king’s trial a committee from among the commissioners was appointed by the Court to ‘peruse and consider the whole narrative of the proceedings of the Court, and to prepare the same to be presented to the House of Commons’. William Say, MP for Camelford in Somerset, was tasked with compiling a record of the events and was instructed to present it to the House by 5 February 1649, less than a week after the execution of Charles.

Order to draft the proceedings of the trial, given to William Say, MP for Camelford

Despite an order dated 9 February 1649, stating that the ‘Narrative of the Proceedings…of the High Court of Justice…be forthwith brought into this House’, as well as follow-up orders dated 16 February and 30 March 1649, it was not until 12 December 1650 that Say presented the House of Commons with the account and that this was ordered to be ‘recorded, to remain among the Records of Parliament for the Transmitting the Memory thereof to Posterity’.

The House of Commons also ordered that the proceedings were to be ‘ingrossed in a Roll; and Recorded amongst the Parliament rolls’. The Clerk of Parliament was then issued with an order by the Lords Commissioners of the Great Seal of England that the document was to be deposited in Chancery, for safekeeping and to ‘be kept there of Record’.

Two surviving accounts

In fact, two separate (and almost identical) accounts of the trial have survived, based upon the notes of the clerks of the High Court, Andrew Broughton and John Phelps. The volume held by The National Archives, often called ‘Bradshaw’s Journal’, is signed by the clerks.

The other copy is the roll that was ordered to be engrossed, or copied onto parchment, and deposited into Chancery. This order was carried out in early March 1651 and was signed by John Phelps to be a true record of the trial. It now lives in the House of Lords archive at Westminster Palace, because it was returned from Chancery’s custody in July 1660 when Charles II was pursuing the regicides and was never returned to Chancery.[1]

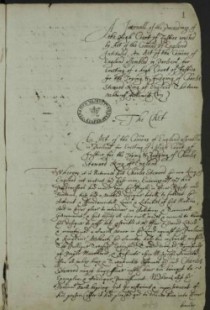

The act to establish the High Court of Justice that was passed on 4 January 1649

The record of the trial recounts in great detail the process that the High Court of Justice went through in the weeks preceding the trial, as John Bradshaw and the Commissioners prepared the charges against the king and attended to the necessary practical matters in Westminster Hall, where the public proceedings were held.

The volume is chronological and opens with the act to establish the High Court of Justice, passed by the Rump Parliament on 4 January 1649, and defiantly asserted the court’s authority over the king. The almost daily entries relate how the court attended to the practical considerations of re-purposing Westminster Hall to accommodate the trial and the construction of temporary public galleries.

The Commissioners also made special preparations for the king’s lodgings for the duration of the trial, including how many guards he would have, and how he would be brought in to and out of the court in order to ensure that no jailbreak attempt was made to free the king.

The trial of Charles I commences

On 12 January, John Bradshaw was formally appointed as Lord President of the court and by 18 January, the charges against the king had gone through several rounds of revisions and the Commissioners were ready to confront Charles.

These entries are among the most dramatic in English history and the verbal exchanges between Bradshaw, the court’s solicitor, John Cook, and the king have been the source of much debate.

When Charles refused to acknowledge the charges against him or the authority of the court to lay these charges, the Commissioners took the decision to deny the king the right to speak to the court until he answered the charges.

His continued spurning of this offer sealed his fate and on 26 January the Commissioners decided to execute the king. He was publicly informed of this on 27 January. From this date on, he was a dead man walking.

‘Tyrrant, Traytor, a Murtherer, and a Publique Enemy’

Declaring the king ‘a Tyrrant, Traytor, a Murtherer, and a Publique Enemy to the Comon Wealth of England’, John Bradshaw launched into a lengthy admonition of Charles. Previously, Bradshaw had constrained himself to only dealing with the charges as laid out in the act accusing the king of treason. Now, however, Bradshaw had no such inhibitions and the king was accused of mass murder and the shedding of blood in violation of God’s law. Furthermore, Bradshaw claimed that the court had been summoned out of its duty ‘both unto God and unto the Kingdom’, and Bradshaw hoped that God would give Charles a sense of his sins so that he might repent before his death.

Charles faced his execution with poise and it was his candour in the face of death that helped to shape his posthumous reputation. His supporters and detractors expended considerable energy in the years after his death justifying their reasons for criticising or promoting the regicide.

The House of Commons assembled in Parliament was assiduous in its preparations and note-taking, as they sought to act without precedent to try to execute a lawful king for crimes committed against his own people. It is through these records that we can assess the events in Westminster Hall that resulted in the execution of Charles I.

[1] M. Bond (ed), The Manuscripts of the House of Lords, vol. 11 Addenda 1514–1714

an ancestor of mine signed the document of beheading of Charles 1..the name is Corbett..how were these men selected to view death of charles1.?

this isn’t exactly family stuff ,,just reading British history..and role of monarch ruling politicans and people of britan …I’m Canadian fyi

Hi Joyce, the regicide judges were chosen by selecting pretty much anyone who might be qualified to do the job by test of intellect, social standing or military rank. First of all the Rump Parliament passed a Bill affirming its lawful authority to try Charles and citing a couple of precedents. This Bill of itself was an act of extraordinary audacity and the Lords rejected it (and it could hardly receive royal assent!) so that ruled out the lords and judges from the ensuing process.

Secondly, Parliament had to find people it could summon to serve as judges – or commissioners. This was no easy task. The original intention was to select 135 but in the end only 88 actually turned up. Quite a few of those summonsed were given no prior notification of the extraordinary task they would be obliged to undertake. Because the Attorney General’s Office washed their hands of the affair Cromwell had to rely on an experienced lawyer from the London Sheriffs Courts named John Bradshaw who had sufficient gravitas to lead the proceedings (he later became President Bradshaw of the British Protectorate once the country became a republic). Fellow commissioners included intellectuals known to Cromwell such as Dr Isaac Dorislaus and other ‘men of quality’ like the radical preacher Hugh Peter plus army men sufficiently seized of the importance of the occasion to countenance sitting in judgement upon the king.

I think that Charles Should have been Allowed a Jail Sentence so as to spare his family the anguish of seeing Him Executed. He was not the worst of Rulers in the Realm of Britain. Henry VIII was a Tyrant who got away with Murder literally. I Believe many thousands Suffered Death at His Hands.

I am trying to find the speech that was made condeming Charles I.

It begins:”The advocates of Charles, like the advocates of other mal factors”