I am part of the volunteer team led by Bruno Pappalardo at The National Archives which, having completed the Navy Board letters project, has now moved on to cataloguing letters sent by Royal Navy Captains to the Admiralty found in the series ADM 1 for the period 1793 to 1815.

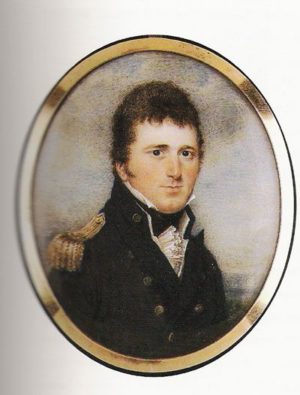

Leading up to the 203rd anniversary of Jane Austen’s death in 1817, I have been lucky enough to work on and catalogue numerous letters in the document reference ADM 1/1453, from Jane Austen’s elder brother, Francis William Austen (1774-1865). He was a Royal Navy Captain from 1799 to 1830, who later became an Admiral and was knighted. Jane had another brother, Charles Austen (1779-1852), who also was an Admiral in the Royal Navy.

The following is a summary of one tragic incident, recounted by Captain Francis William Austen in these letters, which centres on his investigation of a murder.

On 23 January 1810, a gang of three sailors was involved in a fight with some locals in Canton, where one Chinese man was killed. The Chinese authorities claimed that they had come from a British Naval ship and insisted the men be handed over for punishment before they would give permission for the East India fleet, with its rich cargo, to sail before the monsoon arrived. The man charged with investigating the murder, rescuing the fleet in time to sail safely and with preserving Anglo-Chinese trade relations, was Francis William Austen.

Francis was a successful Captain, grown rich with prize money like Captain Wentworth in Jane Austen’s last completed novel Persuasion (1817). He was also well-known for the care he showed to his men and for having strong religious views, resulting in him running a ‘praying’ ship. In 1810 he was Captain of HMS St Albans and the Senior Naval Officer in Canton. All British trade with China came through Canton under strict control of the Chinese. Foreigners had to stay in their designated compounds or factories, being forbidden to trade without a chop (or official document), carry weapons or learn Chinese.

The Chinese officials alleged that a gang of three men came ashore, possibly from the Royal Charlotte. They were drunk and, having bought daggers, tried to buy girls and pay for them with a bad dollar. In the ensuing fracas with seven Chinese, Hoan a Xing, a shoe maker, was stabbed and died. This was confirmed by two witnesses, Chui a Te and Hang a Ko; the others ran away. The local mandarins said they would not give permission for the East India fleet to leave, with its naval escort, until the men were handed over. Captain Austen argued that unless a witness was produced for him to question, there was no proof the murderer was from a British ship, as American sailors were staying very close to the scene.

‘The object of the English is not to screen the guilty person. They are desirous of bringing such a person to punishment but can never admit anyone to be guilty until ample proof is produced.’

Letter to the Viceroy of the area, 12 February 1810.

Captain Austen demanded that the witness, who said he could identify the men, be produced but this was refused.

‘I insisted that as there was no proof that the offence was committed by an Englishman, we should not admit to the fact. Nor had we any means of discovering the offender.’

Austen also wanted the fleet to leave without permission because of the expense of staying and the imminent arrival of the monsoon, which would make the journey home extremely dangerous. However, the representatives of the East India Company, under J M Roberts, said that the fleet could not leave until the Chinese gave a chop or permission, because of difficulties this would cause for trade with China in the future.

The Emperor’s Viceroy refused to see Austen, who was kept waiting for hours at court, and his letters were returned unopened. Austen writes some frank and derogatory descriptions of the officials expressing his frustrations of dealing with local mandarins without adequate translators:

‘A mandarin is not a reasoning animal, nor should he be treated as one.’

‘You know the pertinancy with which they adhere to any opinion they have once affirmed…in defiance of Justice, Equity or common sense.’

In an effort to bring pressure to bear on the Viceroy, he wrote to the Tartar Military commander, Ciang Kium, who was licensed by the Emperor to spy on the Viceroy, but his letter was returned unopened. It seemed an absolute impasse with time running out to get the fleet safely home:

‘When I refer to these obstacles and the general character of the people, I cannot help feeling in how a very arduous situation I am placed and what important consequences may result from my actions.’

The Chinese mandarins stated that if the circumstances were the other way round, the British would insist on a Chinese man being handed over, but any sailor given up to them would not receive a bad punishment. The local Chinese merchants

‘again asserted the necessity of bringing some man forward as the criminal as a matter of form.’

It was essential to devise some solution to save the face of the local mandarins as the Viceroy and the Emperor did not want bad relations with the British. A compromise was suggested whereby Captain Austen promised to take the possible suspects home and try them in Britain after collecting evidence in Canton.

Finally, events began to move when an inquiry was held on 11 February. There is a seven-page transcription of Austen’s examination of the two witnesses available. This tries to establish facts and points out flaws in witnesses’ statements; for example, one man said it was moonlight and the other that it was very dark but still said he could see the sailors’ blue jackets.

Transcript of part of Austen’s cross examination

‘How did you know these foreigners?‘

‘I saw them at noon 10 days before.‘

‘Should you know them again?’ (to identify them from the crew of the Royal Charlotte).

‘I should not.‘

‘How then could you know these men in the dark after an interval of 10 days and yet be unable to identify them later?’

Next witness:

‘How did you know they were British?‘

‘I knew them by their clothes. They were all dressed alike in lacquered hats and short blue coats.‘

‘Did they wear their hair in tails?‘

‘I know not.‘

‘Do not all foreigners dress alike?‘

‘The witness gave no answer.’

On 12 February Austen summarises the evidence and states his case in a letter to the Viceroy. He asks permission for the fleet to sail immediately. Austen suggests there is no proof against the British.

‘Of all the English Captains, only one had any of his sailors in the Canton that evening and they were all locked in the English factory and not one of them had a lacquered hat.’

Witnesses had not been produced and those that are questioned contradict each other. He states that it could have been the Americans but he will investigate on the way home, punish any culprit and communicate the result to the Chinese.

At last the Chinese opened the port and the fleet sailed. On 5 March while at sea, Austen received a letter from J M Roberts, Chief of the East India Company in Canton. Roberts wrote that Captain Wedderburn of the Cumberland, an East India ship, had stated that some of his boat crew were involved in a fight with the Chinese. Roberts justifies his failure to report this information earlier by writing:

‘From the absurd and arbitrary proceedings of the Chinese, I did not consider we were called upon to pursue enquiries…At the same time I was aware that if a man had been brought forward it would never have been supposed to have proceeded from a wish to promote justice but to arise from our apprehension of their idle threats. This would cause much serious inconvenience in the future.’

Roberts does insist that the culprit be found and the result communicated back to him, so he can inform the Chinese and maintain good relations.

The fleet sailed on via Malacca as it was so late in the season. The East India Company wrote a letter praising Captain Austen highly for his skill and tact. He comments:

‘It is highly gratifying to know that my conduct is not deemed deserving of censure especially when I consider how the public service has benefited from a deviation from the letter of my orders.’

Finally at St Helena a court martial could be held on 24 May 1810. Captain Wedderburn’s log was examined, which stated that on 4 February, James Somerville, Captain’s Steward, was informed by Robert Guest, the butcher, that John James, Thomas Matthews and John Wynn had murdered a Chinese man.

Captain Wedderburn had examined James, Matthews and Wynn, as noted in his log on 21 February. They had confessed to buying knives and getting into a fight over a fake dollar bill but denied murder. Wynn was whipped because he had bought a knife but as the others had not, they were let off.

At the court martial, Robert Guest was examined again but changed his story to state that it was just an ordinary fight with the Chinese. On being asked why he had reported such fight in February, when it was such an everyday occurrence, he stated that he was worried about being thrown overboard if he said anymore.

The others were examined to try to establish whether they were drunk, who struck the blow and whether the man was dead or lightly injured. They deny everything except trying to rescue James when he was attacked by the Chinese. On 25 July, Austen wrote he could not establish who had stabbed the shoe maker and that the men

‘were avowedly aroused with drink…and it is highly probable that the fatal wound was inflicted by one of them but I cannot determine how justified it was as a means of self-defence.’

So he took all three on board his ship to bring them home so they could be investigated.

Reading Captain Austen’s letters about this to the Admiralty makes it clear just how much responsibility, not only for naval matters but for diplomacy and trade, was given to British Naval Captains. The letters are extremely detailed because Captain Austen is careful to explain his actions and to justify himself as he had no superior he could refer to.

‘When I refer to the obstacles and the general character of the people, I cannot help feeling how a very arduous situation I am placed in and what important consequences may result from my conduct.’

He would not have known while conducting negotiations that it would turn out so successfully for him, although not for the Chinese shoe maker. He went home to Chawton after this, and one can imagine him telling his family about the events and directly feeding Jane Austen’s literary imagination. No wonder the naval characters in her books are some of the most interesting and complex men in her novels.

I love Jane Austen’s novels. It’s so interesting to have an account of the kind of life and responsibility that her brothers had as they moved up the ranks to Admiral. Respect for the navy and its valour and hardships are always in the background , particularly in Persuasion and this account shows how close she was to that’s experience.

It is an interesting commentary; but it also shows very clearly that the British did not think the Chinese were equal as men but were people to be used for enrichment of East India Company. It would be interesting to know if Austen transported opium to China from India before he filled his ship with Chinese goods to take back to England .