In the latest of our #Readeption550 blogs, Dr Hannes Kleineke from the History of Parliament joins us to take a closer look at the events and records of the Readeption Parliament.

For most of the Parliaments of the later middle ages, the records are remarkably full. The principal decisions taken and acts passed, along with some procedural material, like the election of the Speaker of the Commons, were recorded on the Parliament rolls compiled by the clerk of the Parliaments after the end of the assembly. In addition, original acts of Parliament and even some rejected bills and petitions survive in considerable numbers, offering important insights, such as the House in which a measure was first introduced. The names of many of the Members of the House of Commons can be established from the original election returns sent to Westminster by the county sheriffs.

The exception to the rule was the Parliament that met during the months of Henry VI’s Readeption in 1470-71. For this Parliament, no Parliament roll survives, and few original acts or bills have been identified. The election returns for the assembly are lost, and what names of MPs are known have been gathered from local records. What makes this state of affairs all the more extraordinary, is that the late medieval English Crown was generally at pains to maintain administrative continuity and an unbroken record, irrespective of changes of ruler or dynasty. Thus, one of the first acts of the Parliament summoned after Edward IV’s accession in 1461 was to declare that even though the three Lancastrian monarchs (Henry IV, Henry V, and Henry VI) had occupied the throne unlawfully, their acts were to remain in force.

‘Rex de facto sed non de iure’

(‘King in deed but not by right’)

The phrase used henceforth to describe these kings was ‘King in deed but not by right’. There was no ‘damnatio memoriae’ similar to that known in classical antiquity, when the images and even the names of deposed emperors would be wiped out as far as possible by the destruction of their monuments and the defacing of any inscriptions that mentioned them. Even in the aftermath of the battle of Bosworth, Richard III’s name might be blackened by the victors, but the acts of his sole Parliament were allowed to stand.

Arguably, the administrative arrangements for the Readeption Parliament were inauspicious. When Edward IV had taken the throne in 1461, John Faukes, the long-serving Clerk of the Parliaments who had himself done much to reform record keeping in the House of Lords, remained in post, and he introduced into the Commons his longstanding factotum, Thomas Bayen, as their clerk. Yet, Faukes was no longer a young man, and in the political crisis of 1469-70 nobody seems to have asked the question of how long he would be able to continue in post. It is reasonable to suppose that by the autumn of 1470 Faukes, who would die in early February 1471, was no longer able to carry out his duties. It was nevertheless left to the very last minute to find a successor.

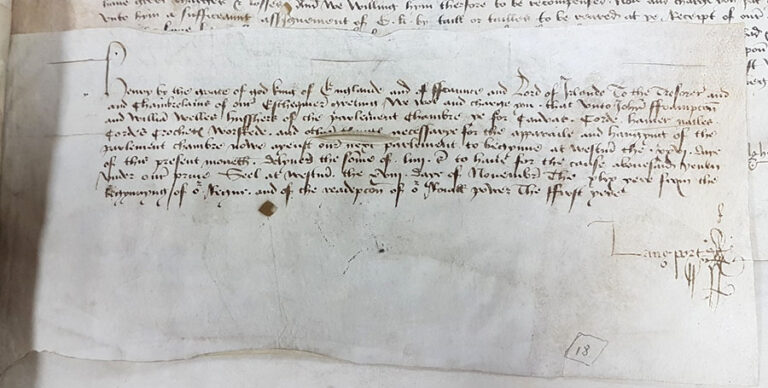

Two days before Parliament was to be opened, the Chancery clerk Baldwin Hyde was appointed clerk of the Parliaments, hardly time enough to find out about the conventions and procedures that governed such an occasion, although it seems probable that Bayen may have been available to offer advice. Hyde, like Bayen, had long been acquainted with John Faukes, under whose successive deanships he had served as a canon of the royal colleges of St. Mary, Hastings, and St. George’s, Windsor, and both men had put their administrative skills at the service of the Windsor community. It is thus not impossible that Hyde’s appointment was ultimately made on his predecessor’s recommendation.

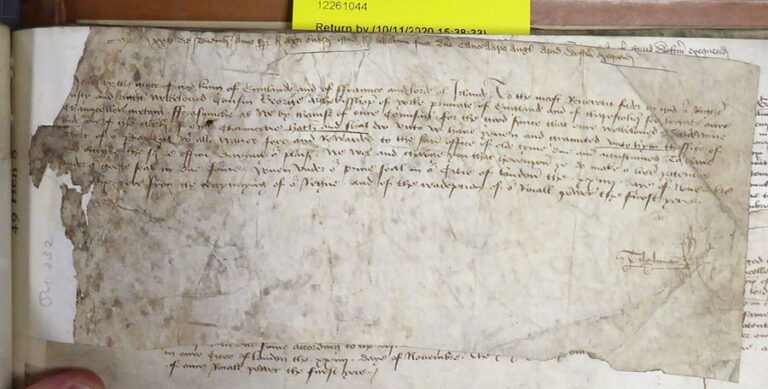

The Clerk of the Parliaments, in spite of his special title and salary, was just one of a number of senior clerks in Chancery, the royal writing office at Westminster. As medieval Parliaments, and particularly those of the 15th century, met only occasionally, he spent much of his time overseeing the issue of royal writs, as his peers also did. There is thus no reason to suppose that Hyde found any difficulty with the normal process of record keeping during the 1470-71 assembly itself: the collection and filing of the records of Parliament was a normal and well-established function of Chancery.

The Readeption Parliament met at Westminster on 26 November 1470. At some point in subsequent weeks, the assembly moved into the city of London, to the Bishop’s Palace, where the restored Henry VI had been accommodated. Here the Lords and Commons met until 20 December, and they returned after Christmas for a further session from 18 January to about 22 February 1. At this point, the Parliament may have been prorogued, the intention being that it should reconvene after Easter. Any such plans would have come to nothing on account of Edward IV’s return, and – as had been the case in 1461 – the assembly may never have been formally dissolved.

While the lack of a dissolution may have meant that the knights of the shires lost their parliamentary wages (writs de expensis for the representatives of the shires were routinely issued on the final day of any Parliament), it would not have prevented Hyde from compiling a roll from the records he had gathered over the preceding four months: in 1461 John Faukes had likewise done so.

It does indeed seem that the records of the Readeption Parliament were kept, and survived for a number of years, only to be officially destroyed in the wake of the fall of George, duke of Clarence, in 1478. This highly unusual step may itself have resulted from one of the most contentious measures – now lost – to have been transacted in 1470-71. As part of the settlement negotiated by the Kingmaker earl of Warwick, Richard Neville, with Henry VI’s queen, Margaret of Anjou, in the Summer of 1470, it was agreed that in the event of the failure of Henry VI’s line, then represented only by his son, Edward, Prince of Wales, the crown should pass to the duke of Clarence and his descendants. This represented a double insurance policy for Warwick, for his two daughters and heiresses were married to the Prince of Wales and the duke of Clarence respectively, and his grandchildren were thus effectively guaranteed the throne.

As this contravened the line of succession established in the parliamentary accord of 1460, which settled the crown immediately after Henry VI’s death on the duke of York and his descendants in order of seniority, a fresh act of Parliament was required. In the course of his trial in 1478, Clarence was accused of having kept an exemplification of this act, and while there has been some debate over the veracity of this accusation, the decision of the 1478 Parliament formally to annul the proceedings of 1470-71 in their entirety lends some degree of credence to it. It is impossible to be sure whether as a consequence of this act the Parliament roll of 1470-71 was also officially disposed of, or whether it fell victim to a later collector who kept it as a curio.

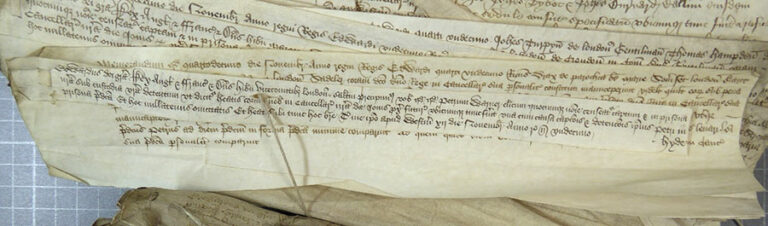

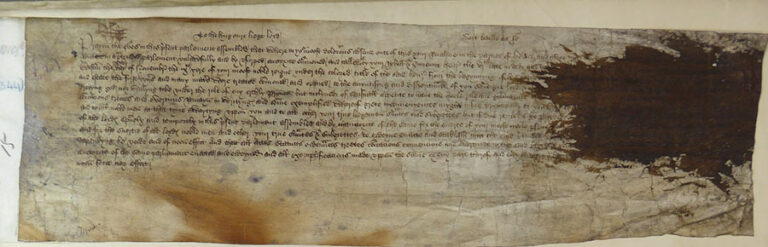

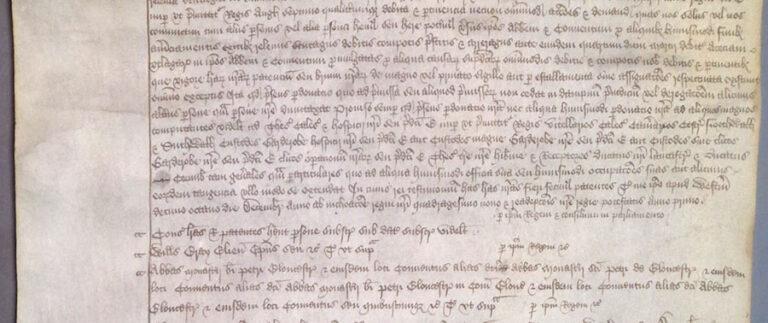

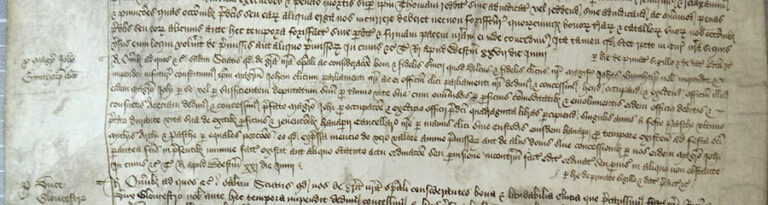

Some records of proceedings in 1470-71 nevertheless remain. Perhaps the single most substantial survival is the roll of the general pardon granted just before Christmas. Such pardons, exonerating an individual or corporation from any charges brought by the King for a specified range of offences, were periodically made available in the later middle ages, and as often as not, were proclaimed in Parliament. This seems to have been the case in December 1470, when the individual pardons were – uniquely – warranted ‘by King and council in Parliament’, rather than by the normal clause ‘by the King himself’ (‘per ipsum Regem’).

There are scattered references to a number of private matters put forward: the abbess and convent of Syon were quick to insure their possessions and privileges against any measures taken by suing out a proviso, the city of Exeter did the same, and it is probable that it fell to Baldwin Hyde to do likewise for the college of St. George’s, Windsor. A number of cities and towns are also known to have pursued their interests in the assembly. The city of Exeter was presumably just one of many corporations who kept a close eye on proceedings: Richard Druell, one of the city’s MPs, was subsequently paid 7s. 10d. for a copy of ‘diverse bills of Parliament in the time of Lent’.

Whether or not Hyde began to compile the roll of the Readeption parliament following its dispersal in mid-February, his labours were certainly brought to an end by his unceremonious dismissal as clerk of the parliaments on 21 June 1471, when the wages of his successor, John Gunthorpe, backdated to Edward’s return at Easter.

Hannes Kleineke is the Editor of the 1461-1504 Commons section of the History of Parliament.

Further reading

Hannes Kleineke and Euan C Roger, ‘Baldwin Hyde, Clerk of the Parliaments in the Readeption Parliament of 1470-1’, Parliamentary History, xxxiii (2014), 501-10

The Parliament Rolls of Medieval England ed. Chris Given-Wilson et al. (16 vols., Woodbridge, 2005), xiii. 391-94

Notes:

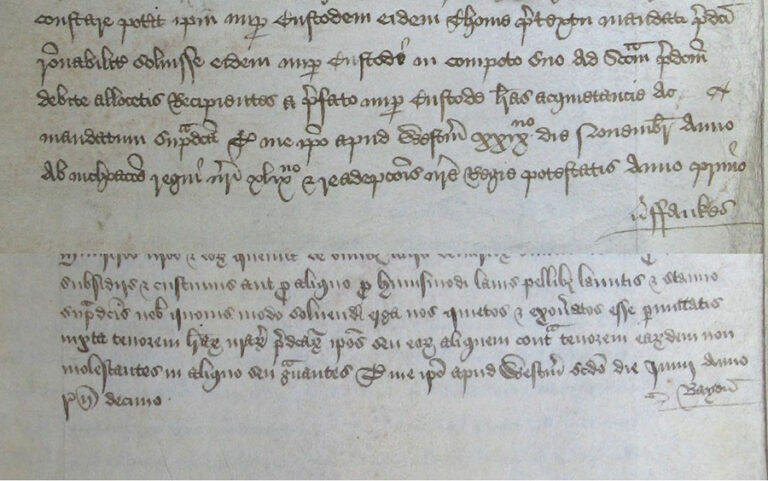

- The dates of the parliament can be established from the records of St George’s College, Windsor, who paid Hyde during his time as Clerk of the Parliaments, but recorded his absence on college business for the dates Parliament sat (indicating that he was also supposed to be keeping an eye out for any business that might affect the college): St George’s College Archives, V.B.II, ff. 15v-17. ↩

As the word “readeption” does not seem to appear in any modern dictionary, perhaps it might be useful to insert a definition in this article.