Born 111 years ago today, Douglas Bader would grow up to be a Royal Air Force (RAF) fighter pilot and flying ace responsible for more than 20 aerial victories during the Second World War. But his success stalled in August 1941 when he was forced to bail out of his plane over France, and he was subsequently captured by the Germans, ending up at Colditz prisoner of war camp until its liberation in 1945.

Colditz was the subject of my last blog, and this one is the latest in a series to promote and celebrate the work of more than 20 dedicated on site volunteers cataloguing in detail some 200,000 British and Allied prisoner of war personnel history cards in the record series WO 416. Over the next two years we hope to complete this project, allowing users to search records by name of prisoner of war and to request digital or paper copies of those cards.

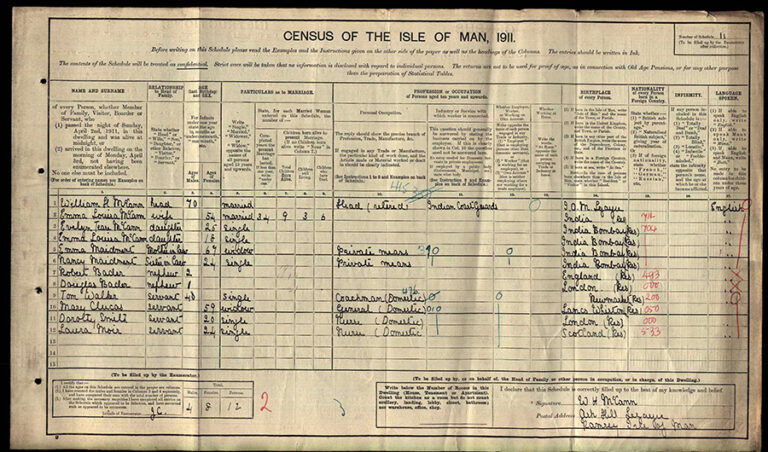

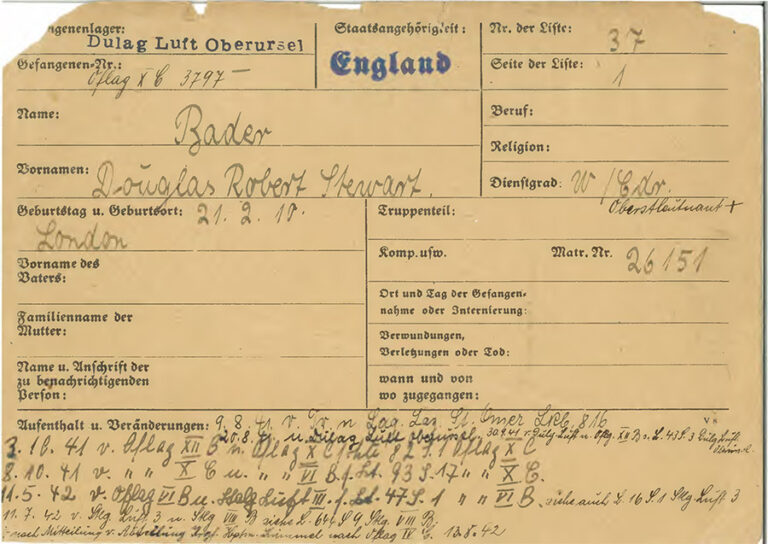

Douglas Robert Steuart Bader was born on 21 February 1910 to parents Frederick Roberts and Jessie Bader in St John’s Wood, London, although in the 1911 Census 1 he is found staying with relatives on the Isle of Man as he was considered too young to return with his mother to the family home in Sukkher in India.

Less than a year after joining them in 1912, his family returned to England permanently and settled in Kew, Surrey. His father was commissioned into the Royal Engineers and went to France in 1914. In 1917 shrapnel badly wounded Major Bader in the head, and he subsequently died from his wounds in St Omer, France, five years later when working with the War Graves Commission 2.

Bader’s fascination with flying stemmed from his elder sister’s husband, Flight Lieutenant Cyril Francis Burge, a flight lieutenant in the newly formed RAF during the First World War 3, and Bader, as a teenager, would often visit Cranwell, where Cyril was stationed at the RAF college.

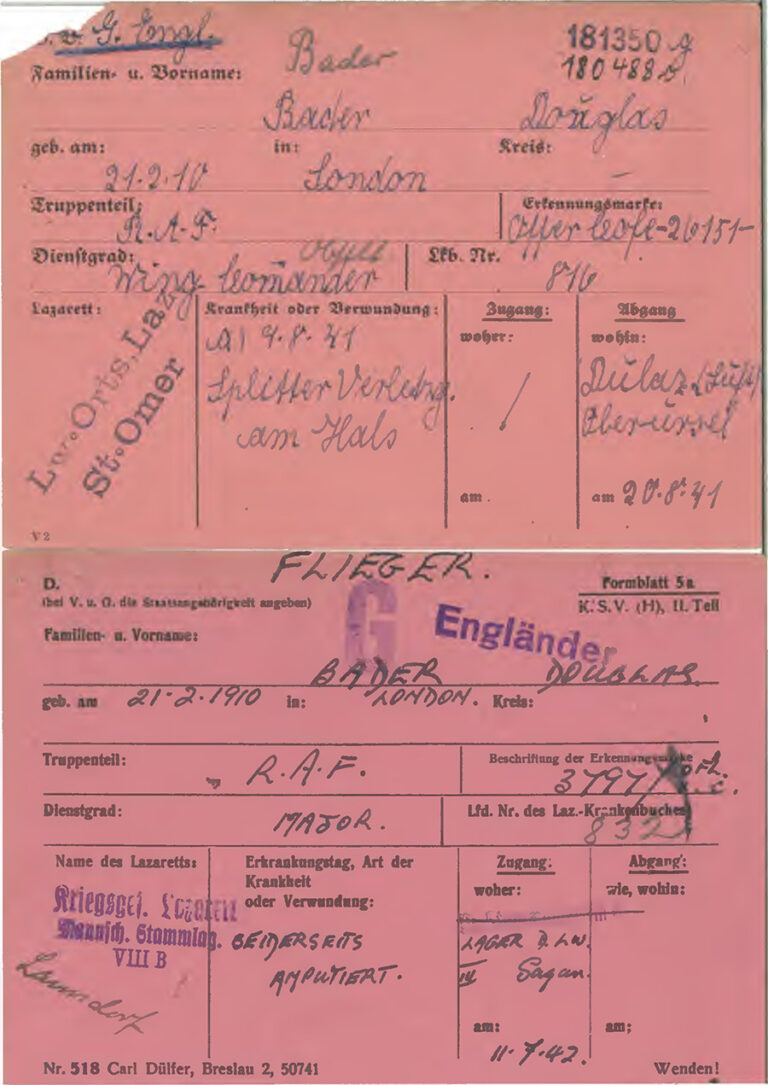

Bader himself joined the RAF as an officer cadet in 1928, aged 18, and was commissioned in 1930 but on 14 December 1931, aged just 21, while attempting aerobatics, Bader suffered horrific injuries when his plane crashed to the ground and exploded. Bader had to have both of his legs amputated.

After a long period of recovery and recuperation, Bader learned to walk again with the aid of artificial legs and was determined to take up flying again. The Central Flying School reported that Bader could fly well but couldn’t pass him fit for flying because there was nothing in the king’s regulations that covered Bader’s extraordinary case, so he was invalided out of the RAF in 1933.

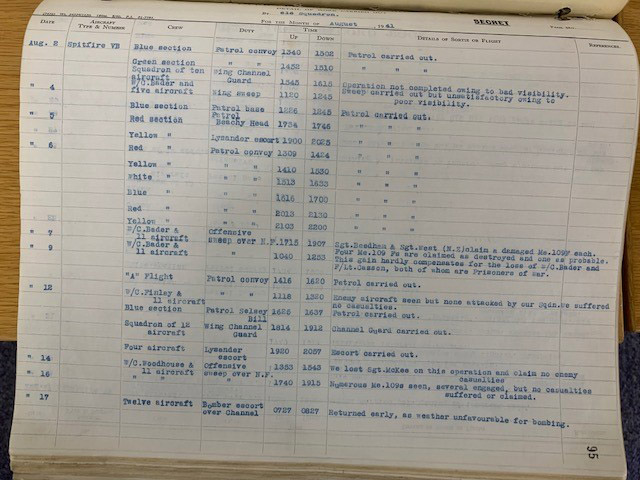

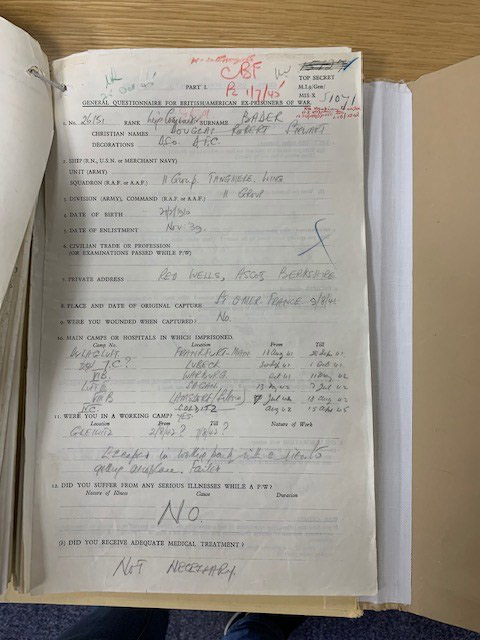

With tensions rising in Europe, Bader reapplied to join the RAF, and finally, in November 1939, he was assessed to be fit for flying. Involved in the Battle of France, Bader was assigned 242 Squadron, becoming Squadron Leader during the Battle of Britain. By the end of 1940, 242 Squadron had destroyed 67 enemy aircraft for the loss of six pilots. The squadron had been awarded one Distinguished Service Order and nine Distinguished Flying Crosses.

In March 1941, Bader was promoted to Wing Commander. Stationed at RAF Tangmere, Sussex, with squadrons 145, 610 and 616 placed under his command.

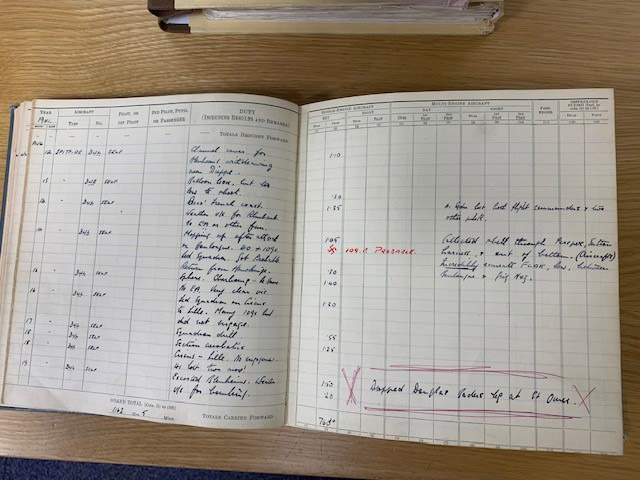

On 9 August 1941 Bader, flying with 616 Squadron in his Spitfire, was involved in a dogfight at 30,000 feet over the coast of France. His plane was badly hit and he bailed out, losing his right artificial limb in the process 4.

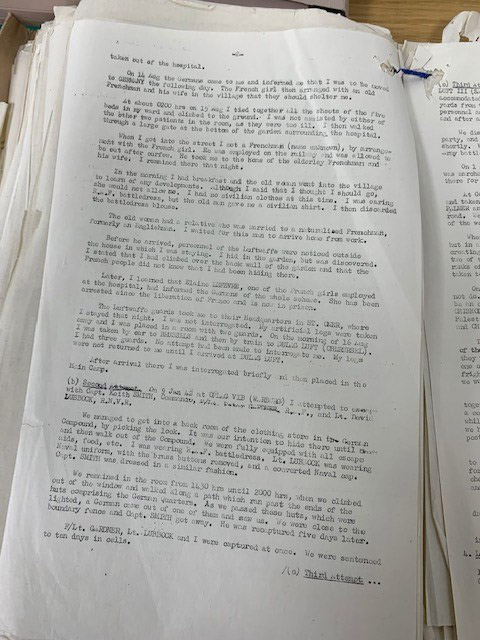

Three German soldiers found him and carried him to the nearest hospital in St Omer, close to where his father was buried 20 years previously. Bader requested that the Germans radio England and ask them to send over a second leg. Although his missing right leg was found, it was badly smashed but repaired sufficiently to wear. So much so that it was at this point that Bader made the first of three escape attempts 5 on 15 August, though he was caught within 24 hours by the Luftwaffe and transferred to Dulag Luft in Oberursel, an allied aircrew reception centre, where prisoners were interrogated before being dispatched to Stalag Luft camps.

Back home in the UK Bader’s disappearance received much coverage in the press 6.

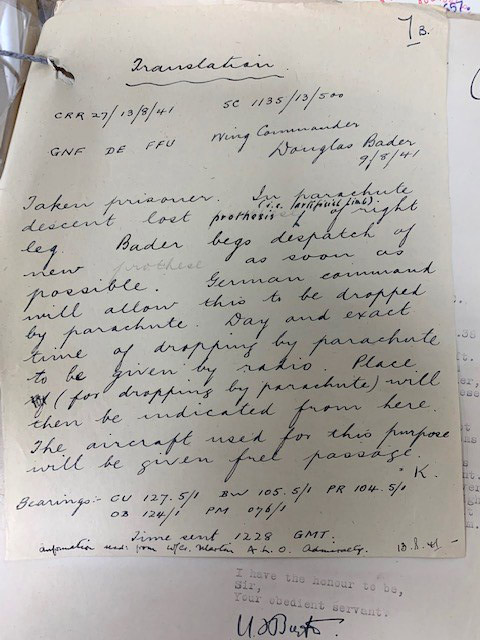

Meanwhile, with the permission of Reichsmarschall Goering, the Luftwaffe radioed England for a new leg providing unrestricted access over St Omer. It was sent in a Blenheim on a normal bombing raid on the night of 19 August 1941. At 15,000 feet, just south of St Omer, the leg was dispatched with stump socks, powder, tobacco and chocolate 7.

Reunited with his artificial legs, and unable to get on with his captors, Bader was transferred to the officers’ camp Oflag VIB in Lubeck and later to Stalag Luft III in Sagan. It was here he met Group Captain Harry Day and Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm pilot Jimmy Buckley. Day would go on to be part of the famous ‘Great Escape’ from Stalag III in February 1943.

Bader joined the Escape Committees in the various camps he was sent to, but his roles in escape attempts were often restricted to ‘goon-baiting’, where he attracted the attention of his captors away from any escape operation. For example, when German squads strode past singing marching songs he organised men to whistle opposition tunes and put them out of step.

Bader, himself so desperate to escape, was disappointed as the Escape Committees had serious doubts about his success, though two ultimately unsuccessful attempts were made at Oflag VIB and Stalag VIIIB in Lamsdorf. Eventually, Bader was transferred to Oflag IVC at Colditz where he remained until the end of the war, when the camp was liberated by US forces in April 1945. Upon liberation, like all allied prisoners of war he was encouraged to complete a liberation questionnaire 8.

As well as giving personal details, name, rank, number, unit and home address, these records can include: date and place of capture; main camps and hospitals in which imprisoned and work camps; serious illnesses suffered while a prisoner and medical treatment received; interrogation after capture; escape attempts; sabotage; suspicion of collaboration by other Allied prisoners; details of bad treatment by the enemy to themselves or others.

Bader died of a heart attack aged 72 on 5 September 1982, just two months after the film actor Kenneth More, who portrayed him in the 1956 British film Reach for the Sky, based on Bader’s biography of the same name published two years earlier. He will be remembered for a multitude of reasons but it was for his services with disabled people, setting an example of how to overcome a disability, that he was knighted in 1976.

Although Bader’s story has been told many times – not least in Paul Brickhill’s biography ‘Reach for the Sky’ (1954) and the subsequent film of the same name (1956) – it’s great to see some of the relevant documents which are in the care of the National Archives and see how these add to the general narrative.

More please!

A slight correction to the post where its stated ‘Dulag Luft in Oberursel, a prisoner of war camp primarily for those serving in the RAF’.

I believe ‘Dulag Luft’ – officially known as Durchgangslager der Luftwaffe at situated Oberursel near Frankfurt-am-Main – was in fact an Allied aircrew reception centre where airmen were sent for initial interrogation by Luftwaffe Intelligence before being sent to ‘proper’ prisoners of war camps (Stalag Luft III being a well-known example).

Unlike these camps which were to hold prisoners for the duration, Dulag Luft would usually hold prisoners for between two weeks and a month.

During this time the initial shock and disorientation of capture was capitalised on by the Germans with prisoners being asked to complete fake Red Cross forms. Told that the information was to be sent to the Red Cross and then sent on to next of kin as proof of life, these were designed to yield intelligence information.

These tactics were in turn known to RAF intelligence who regularly briefed aircrew on bomber (and towards the end of the war long-range fighter) stations.

Imperial War Museums has an example of an instructional film (Information Please) that would have been been shown.

This can be viewed at https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1060020666 .

You might like to be aware of another correction to information in this post.

As I noted in my original comment above ‘Reach for the Sky’ was a biography of Douglas Bader written by Paul Brickhill and not Bader’s autobiography.

Brickhill was a journalist who later served in the RAF. He was shot down in north Africa and went through the Dulag process before being sent to Stalag Luft III.

There he played a part in what became known as the ‘Great Escape’ (and the subject of one of his books, another being about No. 617 Squadron and the raids on the German dams in May 1943).

A minor correction: Jimmy Buckley was not involved in any way with The Great Escape. He was killed in 1943 (presumably drowned in the Baltic, although his body was never found) after the Abort Dienst from Oflag XXI-B (Schubin), in which my father (Squadron Leader Peter Stevens MC) also took part.

I once bought a book by Paul Brickhill about the Dam Busters at a book sale in my local library. To my delight and surprise there was a typewritten letter signed by the author stuck in it . The letter was addressed to an officer called Kell who had taken over Dambuster Mickey Martin’s Lancaster.

What luck for 50p!

Thanks for your comments, Richard. I’ll amend this error. Bader’s autobiography was “Fight for the Sky”, published in 1973. Also, we have Paul Brickhill’s Prisoner of War cards in WO 416/41/362 – https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C16581991

Thanks for your comments Marc – I’ll get that corrected. We also have Buckley’s prisoner of war cards in WO 416/45/154 – https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C16593414

In several places the blog gives 1942 as the year when Douglas Bader was shot down and captured. This surely should be 1941.

Thanks for bringing that to our attention, Peter. We’ll amend those to read 1941.

Hello Roger, thank you in turn for your comments and for correcting the post.

As they say it’s not about being right, it’s about getting it right!

RAF Battle of Britain ‘aces’ Douglas Bader and Robert Stanford-Tuck were my boyhood heroes. In 1959, aged 17 in my school CCF, I won a Flying Scholarship flying DH83A Tiger Moths at Newcastle Airport. One day a DH Dove arrived, my BoB flying instructors Jimmy Denyer and Dave Davico rushed off to meet its pilot, Douglas Bader, who stumped into the hanger. I have to say I was so thrilled that I lost all presence of mind and did not introduce myself as an accepted RAF College Cranwell cadet, (83 Entry September 1960). As a fighter pilot we all were inspired by Bader’s generation who had saved our democracy, that we all proudly served.

Is this the officer, whose dog’s name was dropped in a WW2 film by the BBC ?

I met Douglas Bader on the 5 September 1982, sadly the night he died this was a Bomber Command Baquet at the Guidhall in London, and gave him a copy of his escape from the hospital at St Omer, WO 208-3339/1244 so its ironic that you have shown this today.

To add this was an occasion to present Sir Arthur Harris a presentation sword, Sir Douglas although Fighter Command was a guest and made a speech, I have a photograph of him at this occasion.

I recall meeting a girl friends father who was in prison with Bader. He said that Bader was not always popular with the other inmates as he kept stirring up trouble with the Germans. Always two sides to a story:-)

As a kid in southern Alberta, Canada, in about 1956 or 1957, I attended an event in which Douglas Bader received a great honour in recognition of his WW II heroism. In an outdoor ceremony, Bader was inducted into the Kainai Chieftanship of the Blood First Nation, part of the larger Blackfoot Nations, as I understand. It was a blazing summer day. The ceremony took place on the open prairie, far for any town. There was a crowd of maybe 60 people. A wooden platform had been erected. Bader sat on the bare wood, with First Nations dignitaries. He was black haired and shirtless. The magnificent full feather headdress of the Kainai chiefs was put on his head. Bader was given a wonderful and apropos First Nations name, I think, Chief Morning Bird. I read Paul Brickhill’s book and saw the film with Kenneth More. Both inspired the rest of my youth.

Further to John M’s comment:

I think the dog to belonged to Guy Gibson who led the “Dam Busters” raid, and the brown dog’s name was the N word. Not considered a bad word back then!

When Bader was a schoolboy, he attended St Edward’s School in Oxford, of which at the time my late uncle, Walter S Dingwall, was bursar. Young Douglas was only 12 years old when his father died in 1922, and it then became clear that he would probably have to leave the school, as his widowed mother was not going to be able to afford the fees. My uncle had spotted his potential, though, particularly his sporting prowess, and discreetly made a private arrangement to pick up the fees himself, personally. Years later, when Douglas was old enough to ride a motor bike, my uncle gave him one as a present – a gift he never forgot (I think he may never have known about the fees). For the rest of my uncle’s life, Bader kept in touch, sometimes visiting him and my aunt at their home in Sussex, and never failing to send a Christmas card. This they enormously appreciated, as they had no children of their own. I hope this little account gives a slightly kinder impression of Bader’s character than the ‘aggressive and competitive nature’ and the ‘strong streak of conceit’ that his Wikipedia page quotes as his headmaster’s opinion of him at St Edward’s.

Hi John M. I think you are referring to the film of the “Dambusters” in which Guy Gibson’s dog’s name was used as a code name to announce the success of the attack. As you may have seen above the book on which the film was based was written by Paul Brickhill.

The name isn’t dropped as such when shown on many television channels but overdubbed as the name – which was acceptable in the context of when the film is set and indeed made – is not offensive to many people, including not only those it might be directly aimed at.

Whether the overdubbing is ‘right’ or not is perhaps outside the scope of this post.

Apologies for being a pedant, but……just a couple of bits and bobs I picked.

Douglas Bader’s parents were Frederick Roberts Bader a Civil Engineer and Jessie Scott MacKenzie and after his birth stayed with relatives on the Isle of Man. The Robert Bader listed in the 1911 Census is not a sibling so must be a cousin. He did have one sibling, an elder brother named Frederick after their father but was called Derick to differentiate. Douglas eventually joined his family in India in 1912 but in 1913 his father resigned his job to study law and the family returned to England.

Flt Lt Cyril Burge was married to Bader’s aunt Hazel, Jessie’s sister, when he first visited RAF Cranwell in 1922. Bader didn’t have an older sister. Burge was ex RFC and was in post at Cranwell as the Adjutant.

Moving on to the crash at Woodley Aerodrome in 1931, the aircraft didn’t explode when it crashed but broke up on impact. Bader’s injuries were grievous as we all know but he didn’t suffer any burns. There was no fire but petrol was leaking from the ruptured tanks and without the quick response of the men on the ground there may well have been. On return to active duty Bader was employed as a logistics officer at RAF Duxford in MT until a decision could be made about his future. You rightly state that there was nothing in KRs to cover his case, CFS passed him fit to fly but there was some unpleasant murmurings in national newspapers from people expressing disquiet about a legless pilot in the RAF. Bader was offered an opportunity to transfer to the Supply and Logistics Branch but declined and left the RAF on medical grounds.

Finally, 242 Sqn was based at RAF Coltishall, it would have been nice to see the old place mentioned. I spent 13 years of my RAF career there.

I’ve read similar about Bader’s time in Colditz, moreso his arrogance.

That is a fantastic story and memory to all involved. Douglas Bader was a fantastic pilot, others were too.

Alan – you were very lucky (if that’s the right word). In any case I envy you the experience.

Eddie – I believe this is alluded to in the film where a scene shows Bader inspecting the escort that will transfer him to another spell of imprisonment.

It’s interesting to speculate what would have happened to many people who found their niche in the World Wars – not just Bader, but ‘Bomber’ Harris and ‘Sailor’ Malan who apparently preferred not to shoot down enemy aircraft but to damage them badly enough so that they could just make it back to their home bases and probably crash-land there.

The ground crew would have the unenviable task of extracting the dead and wounded aircrew, many of whom would have been at least known by sight to those who had to stretchered them away.

Eddie, I heard the almost identical comment years ago from a friend of the family who had been a PoW with him. I think the ‘everybody’s best mate, a team player’ image portrayed in the film was a dose of poetic licence – he could apparently be a difficult character, albeit still a very brave man.

Fantastic post, thank you- as an American, I wasn’t aware of Douglas Bader and his incredible life.

Bader came to NZ back in the 50s. He visited my primary school in Waikanae on the Kapiti Coast. I met him. I have a photo of him when he landed at Paraparaumu airport

Douglas Bader, along with ‘Johnny Johnson’, Leonard Cheshire, Guy Gibson and others were boyhood Heros to us born during the war and at secondary school in the 1950s. I was lucky enough to have Paul Brickhill’s book ‘Reach for the Sky’ as a form prize in 1958. Its now has the various newspaper clips of obits in for some of these chaps. Great people and very inspiring.

I met Bader on 3 occasions wile serving in my parents shop in Huntingdon UK. This would be in the late 1950’s. I still remember him as a rather abrasive personality and a real “classist” to use a modern expression. This makes me understand his fellow prisoners in Colditz rather well. BTW I served quite few well known personalities, but Bader would not be my favourite.

Bader was with the Shell company who flew DH Dove and DH Heron. The aircraft were used by company executives so I assume Bader piloted both aircraft. A friend of mine an aircraft engineer worked with Shell on discharge from the Irish Air Corps who operated Dove aircraft in late 50s early 60s.

As a member of the Variety Club of Great Britain, The Greenham Common Air Show( Douglas was President of the show) invited us to take 200 children to the show to be entertained for the day. Being invited to the Presidents ten for Lunch it was then I met with Douglas Bader. He asked me if I had ever sat in a Spitfire I said no, meet me outside of the tent at 2pm he said. A Chauffeur driven car pulled up outside the tent with Douglas in the passenger seat. get in said Douglas off we went to an enclosed area, where there was a Spitfire – Lancaster-and a Mosquito. My friend would like to sit in these planes say’s Douglas certainly sir said the duty air staff. What a treat a chance in a lifetime. Douglas leant against the wing of the Spitfire I used to be able to swing my legs over there and get in unaided. NO CHANCE TODAY THOUGH he quoted. Not only did the children have a great day at the event but those three hours with Douglas was such a privilage one I will always remeber.

My sister-in-law was an air hostess in the days when their only task was to ensure that the passengers were comfortable. The aircraft wasn’t heated from memory, and Pat had the task of looking after Douglas Bader – not knowing his name or the fact that he had artificial legs she kept covering his legs to keep him warm. Eventually he pulled the blanket away and pulled up his trouser legs and showed her his artificial limbs. I heard this story many years ago and can’t remember the end of the story.

Bader’s father was not buried near St Omer but Brussells – a Brickhill embellishment (one of many). My Bader biography, published by Amberley, refers.

I met Douglas Bader during what I think was the first International Year of the Disabled, I can’t remember the year but it would have been late 70’s. He was guest of honour at a day for people with disabilities at Upton Country Park in Poole, Dorset that was organised by my mother and the Dorset Federation of Townswomens’ Guilds. It took place in the walled garden and I recall the Air Cadets helping being confused about the fact that his car was described as Air Force Blue when it was grey. I have a lovely photograph of my mother apparently sitting on his knee although her weight was actually on the arm of the chair.

I am not sure if this has been mentioned elsewhere but there is a ‘This is your Life’ tribute to Douglas Bader (with Eammon Andrews) which is available to view courtesy of You Tube. I watched the programme quite recently and it seemed to capture the mood of the generation.

Further to Eddie Lord’s and Margaret Mills’ comments:

My late uncle F/O Eric Baker, who was also a POW in Stalag Luft III, once remarked to me that Bader became unpopular with his fellow inmates because he made a regular and deliberate practice of being late for roll call while every one else was kept waiting outside on cold and snowy mornings. Such petty obstructionism can, I suppose, be seen as the flipside of the obstinacy and great courage he brought to his career as a very effective fighter pilot.

This must be the same Douglas Bader that I read so much about in the 1950’s in the RAF Flying Review and the same guy who developed the skipping, dam-buster bombs. He was certainly a hero of mine.

Douglas Bader was a guest speaker at my school (Rondebosch Boys’ High in Cape Town, South Africa) probably in 1962 or 3. I was about 15 at the time and was spell-bound as I had already read ‘Reach for the Sky’ (still on my book shelf) and other Paul Brickhill books. My father was a squadron leader in the RAF posted to South Africa during the war where he met my mother and hence me!

I have learned that people who achieve greatness through hardship and opposition usually are not cuddly agreeable teddy-bears. Take Churchill for example!

Further details about Douglas Bader’s life…In 1923 when Douglas was 13 years old his mother remarried a Rev Hobbs & so the family moved to the Vicarage in Sprotbrough, Yorkshire – a move, according to a Doncaster historian made note such a move was not welcome by the 2 sons! But he and his brother very soon became known in Sprotbrough by their antics (pity their neighbours). Douglas was also said to have flown over the vicarage and parachuted a birthday present to his mother. This I can believe as my mother told me that he used to fly very low over the tall poplar trees she had planted many years before at the bottom of her parents garden.

In 1934 my parents married and they had a house built on Boat Lane just a house and field between their site and the Vicarage. We lived there until I was 6 and the Vicarage, being surrounded by high walls seemed ‘impenetrable’ to my sister and I and definitely out of bounds!

Many years later after the Vicarage was sold and renovated my sister spent a Happy 70th birthday in the Spitfire Room, so she finally was able to enter through the gates and enjoy all the memorabilia the new owner had collected.

First of all, it was great to get ‘eyes on’ the original documentation! I have three observations. It states that the Great Escape took place in February 1943. I’m pretty sure that the mass breakout from Sagan took place on 24 March 1944.

With respect to Richard’s excellent comments about the camp at Oberursel being a processing and interrogation centre, it is worth pointing out that many PWs were interrogated by the master interrogator Hans Scharff, who would often amaze allied aircrew prisoners with detailed knowledge of individual stations. For example, he might say “Is the clock in the Officer’s Mess at (for example) Bardney still eight minutes fast?” This would disorientate prisoners and throw them off their guard, until they released a piece of information he didn’t have. Apparently the famous 56th Fighter Group ace Col Francis “Gabby” Gabreski (who was warmly greeted by Scharff – “Ah Gabby we’ve been waiting for you!”) was the only PW who never gave away anything to Scharff.

Finally it is interesting to note that Bader’s prisoner Ausweis has his equivalent rank correctly as Oberstleutnant (Lieutenant Colonel) which is the equivalent rank of Wing Commander. However on his medical card his rank is listed in English as Wing Commander and someone has elsewhere written down the Dienstgrad (rank) as Major, which as the Luftwaffe equivalent of Squadron Leader. This lack of attention to detail would not have pleased Bader!

Hello Bill. The Dambusters bomb was the brainchild of Barnes Wallis, a civilian aero-engineer and inventor.

Aged three I contracted the polio virus just before the Salk Vaccines regime and my legs became and remain for life seriously paralysed.

I received an autographed first edition Reach For The Sky from my father, also RAF, who in the mid 50s met Douglas and would have concurred with some of the ‘character’ traits mentioned.

However, Douglas’s story became my life base-line; as boy and young man I read and read the book to destruction (now rebound and still on my book shelf!).

And vowed if he could prevail so could I: now almost 70 years on I can look back on a satisfying and successful international career in defence contracting driven, when the people, the system or challenges said ‘no’, by that man’s extraordinary courage, tenacity and will.

Forever grateful-…… though never hacked the golf swing!

My goodness, great to read so many personal titbits about Douglas Bader’s character and life; but for the unititiated I can say ‘fighter pilots are not chosen for their equinamity, but for their aggressiveness and leadership in the air, not necessarily on the gound’. There are exceptions, my first squadron’s boss David Brook, and flight commanders Jerry Seavers and Al Pollock. In ’66, at RAF West Raynham, I also socialised with Col. Gerd Barkhorn, WW2 Luftwaffe ace many times over with 301 victories, (the wags suggested I might be number 302). He was on the Tripartite Kestrel Evaluation Unit. He exemplified the fighter pilot’s clinical professionalism of Udet, Boelke, Richtoffen, Goering, Ball, Bishop, McCudden, et al., all cool heads under supreme pressure. But only Gerd Barkhorn also survived his war. KP

Hello Keith. This is way, way off topic but is the Al Pollock you mentioned Flight Lieutenant Alan Pollock, RAF who took issue with the Royal Air Force for not (in his view) didn’t mark the 50th Anniversary of the founding of the RAF in 1968 that he buzzed the Houses of Parliament and flew under the walkway on Tower Bridge in a Hawker Hunter on 5 June of that year?

Regardless of whether it’s the same man, the Tower Bridge incident is detailed in Air 20/12324 and Air 8/2462 and apart from the bravado of the incident, Pollock’s story before and after is worth a read.

G’day Richard, not so far ‘off-topic’… Douglas Bader still has his acolytes! And yes, same Al Pollock: I’d left No 1(F) Squadron for CFS or 2 Hunters would have ‘threaded that needle’.

As a pair we wired Norway to test radar-laid guns, told to come in as fast and as low as possible. Carte blanche always brought out our best performances. We regularly talk of those balmy days, Tower Bridge direct from the horse’s mouth is my only source. MoD was one of the problems, no way to hear it.

Erratum.. Hermann Goering survived WW1, but reincarnated as a Nazi – expunged his impressive war record. Mea culpa.

Perhaps someone at National Archives will look at the files and write up the story, that way you and others who recall the flight could comment and the rest of us would be able to see a wider picture.

Richard,

Or, better still, why not speak to Al? He already appears on U-tube, speaking of those ‘two and a half split seconds’ – a lifetime in our job. Believe me or not, the salutory full story as yet is unpublished.

I have only just come across this, so very late, but I wonder if you can shed any light.

In ‘Reach For The Sky’ we hear nothing at all about the older brother, Derick, after DRSB’s childhood. He is not mentioned as having visited DRSB in hospital, or indeed any further at all. He actually died in 1936; were he and DRSB estranged or something?

Likewise, DRSB’s mother completely disappears from the narrative after he leaves hospital an amputee. She’d only have been about 65 when the war ended so what happened to her and where was she while he was recuperating?

I don’t exactly know all the details but as a spitfire engineer in the war my grandad had a dislike of the man, that was apparently shared by many others, due to his arrogance, snobbishness and abrasive manner. And my grandad could get on with most people.That was the story I was always told anyway.

Derick had already gone to South Africa where he would be killed.

I’ve just found photos marked ‘Douglas Bader party on his return from POW camp’. Does this ring a bell with anyone ? Anyone know where he flew into on returning to the UK?

Thanks

Malcolm Lindsay

Regarding Freddie Jones’ Feb 2021 comment on letter to officer Kell from Paul Brickhill in the 50p Dambusters. Officer Kell was Arthur Edward Kell. He was my father. He took over PPopsie from Mick Martin. Both Mick Martin and Paul Brickhill were friend of my father. Would love to know what the letter said?

When I was a student at the University of London Air Squadron in 1965-68, we flew Chipmunks from RAF White Waltham Airfield, near Reading, Berkshire. As someone has mentioned above, Douglas Bader also flew the Shell Company’s DH Dove and DH Heron from White Waltham. When he returned to the airfield, he was very abrupt indeed when calling Air Traffic Control for permission to join the circuit and land. In fact, the tone of his voice made it quite clear to everyone on the radio frequency that he was going to join the circuit and land regardless of whether or not he was given permission. Indeed, it was quite clear to all other pilots that they immediately needed to “get out of his way”.

In spite of his apparent arrogance, he was clearly a very brave man indeed, and he did not stop “attacking” the Germans even after he had been shot down. He continued to harass them in captivity, which is presumably why he was transferred to Colditz, which the Germans appeared to consider was their most secure Prisoner of War Camp. I regret that I never had the privilege of speaking to him at White Waltham, even momentarily.

In the 1950s, my father was a young waiter at the Royal and Ancient Golf Club in St Andrews Scotland. Not far away was RAF Leuchars.

My father (an orphan from nearby Tayport, Fife) told a story of Sir Douglas Bader visiting the cub.

Apparently he ordered a “Martini in a silver tankard”. As the barman was busy, he instructed the young inexperienced waiter to prepare the drink.

From the (Cinzano?) bottle labelled “Martini”, he poured the drink into the tankard and took it over.

He was later summoned to the table and asked “what did you put in my drink?” to which my father replied “Martini as you requested Sir, straight from the bottle “.

“What, no Gin? Why that’s fantastic, please bring me another! ”

I’ve since learned that Sir Douglas “rarely drank” but my father was not one for exaggeration, nor did he drink much himself so I’m inclined to believe it is a real story.