To mark the 75th anniversary of the Partition of British India, The National Archives has worked with the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London to create a new Key Stage 3 (KS3) Partition resource, which we launched at the beginning of July at the Schools History Project Conference. The Q&A below is based on the presentation given at the launch.

Below you will find out a little bit more about how the project was conceived. You’ll learn about Iqbal Singh’s (Regional Community Partnership Manager at The National Archives) personal journey into this history, Dr Eleanor Newbigin’s (SOAS) practice as an academic and university teacher, and Hannah Carter’s (Education Manager at The National Archives) role in furthering The National Archives’ approach to teaching diverse histories.

Iqbal, what made you want to develop a KS3 resource to mark the 75th anniversary of Partition?

I joined The National Archives in 2015, and one of the early anniversary events I worked on was the 70th anniversary of Partition. In 2017 I collaborated with Bhuchar Boulevard on their production A Child of the Divide, and hosted an event which included a document display and sharing some collaborative outputs with arts and community organisations.

It had been the first time I had looked properly at Partition, and I recall feeling both overwhelmed by the scale and complexity of the topic and also how emotionally testing it was to undertake – which may have been a reflection of my own family history and background (which I will say more about later).

Fascinated by what I had learnt and keen to find out more, I have continued to remain engaged in the study of the topic and in networking with others, including becoming a member of the Partition Education Group. It has become increasingly evident as I have listened to others that for the 75th anniversary, they were keen that more resources be made available to teach young people about Partition.

So last year we conducted a survey of teachers and my colleague Hannah will say more about this. In more recent years, as I have been reminded, it is not that teachers are not teaching Partition or other aspects of colonial history, but that it’s underreported and teachers need better resources.

As a result of the survey we conducted and our aim to mark the 75th anniversary, I helped draw together a group of colleagues and then reached out to academics who might be able to assist (Iqbal adds: Dr Yasmin Khan kindly offered some very helpful insights). I wanted something produced that could to capture something of the community voices I was very close to, have input from Hannah as one of our resident teachers at The National Archives, and have input from someone who was close to the leading debates and issues in the field.

I was particularly struck by the work Eleanor was doing after hearing her presentation last year at an international archives conference where we shared a panel together, and I invited her to take part in developing the video and resource. Later we will hear what Eleanor has been doing in her practice as senior lecturer at SOAS teaching Partition.

Hannah, can you say a little more about how you went about designing a KS3 resource?

In order to decide what resources to develop to mark the 75th anniversary of the Partition of British India, we launched a survey of KS3 teachers. The survey results suggested that most teachers were teaching this topic over one or two lessons. There was an indication it was being taught in the context of colonialism and empire. The responses did not mention the Second World War, however one teacher taught Partition in the context of a longer enquiry about India’s history, stretching back to Mughal rule. We wanted to include a reference to the Second World War and its significance in this story. Quite a few respondents said they did not feel confident teaching this subject. This listed lack of resources, knowledge and limited curriculum time at KS3 as concerns. When we presented this resource at the Schools History Project conference, we received additional responses from teachers that there could be challenges when teaching to a classroom with religious and cultural differences, as well as perspectives on this topic. A key concern arose about addressing the complexities of the topic in the limited time available at Key Stage 3, for instance avoiding a simple ‘blame game’ narrative.

Following the result of the survey we decided to create a resource that could be introductory and was centred around how much archival material could tell us about the Partition of British India. We wanted the film to be appropriate for use by teachers in lots of different ways, in assemblies, form time or as part of lessons about partition.

Eleanor, can you say more by way of introduction to your journey to becoming a historian of South Asia, and now as Senior Lecturer in the History of Modern South Asia at SOAS?

There are lots of factors that have influenced my journey to becoming a historian of South Asia. My dad grew up in India (after 1947). He loved his childhood and spoke very fondly of it, before coming back to Edinburgh which he hated. I also grew up in a very diverse part of south London where lots of people had family across the world. At school we never talked about these different histories – our history was global in that it was about wars and the UN but none of this gave us even a basic framework to begin to ask questions about our own lives and families. This was hugely important for classmates from diaspora communities but I think it also negatively impacted white British people like me.

I started a history degree in 1999 and as part of one course read Urvashi Butalia’s ‘The Other Side of Silence’, a very recently published book by a feminist scholar of South Asia that used oral histories to rethink the history of partition. The book was the most engaging and exciting thing on my reading list. I know now that this was one of the books that really opened up the possibility of thinking about what Partition meant for the people most affected by it – not by state structures. I gobbled it up and wanted to read more and more. I went on to do a PhD that examined debates about South Asian women’s legal rights and how these were changed by Partition.

Eleanor, your reflection is striking that as a university teacher you believe there is a need for a more thoughtful and attentive pedagogy in teaching about Partition, and a need to be aware of who was in the room, who was teaching and how that shaped engagement? How as a university teacher have you gone about teaching this topic?

A few years ago I was asked to teach a course on Partition at SOAS – that had been really thoughtfully designed by another colleague, Dr Amrita Shodan, looking at the history of 1947 from a whole range of different perspectives – political, social, using government archives, speeches, newspapers, oral histories, literature. The whole emphasis in this course is about moving away from a single causal account of 1947 – the question of ‘what caused Partition’, ‘who wanted Partition?’ to try to think more deeply about how a context could be created in which it seemed logical and reasonable to solve a range of complex issues by dividing up territory.

And to also think about the legacies of this division – how the division was experienced when the line was drawn and afterwards. Following the kind of scholarship I read when I was doing my degree, the course is interested in thinking about Partition as a process rather than an event that we can date very specifically to August 1947. It seeks to think about Partition (or partitioning) as a way of labelling and organising people, that began before August 1947 – to make the idea of partition possible – but which is still playing out today.

So the course is beautifully and thoughtfully designed but I was teaching it in a classroom that was diverse like my own school classrooms, where I was one of the few non-South Asian people in the room, but also the teacher – the supposed expert. I found this framing of ‘knowledge’ and expertise in the classroom very uncomfortable and began to talk about it with students in the class. We discussed not only primary sources and ‘factual’ material about Partition but also the different ways that we felt about and related to that material and how these differences shaped our interaction together in the classroom.

Eleanor, you’ve spoken about this difference between the emotional engagement of South Asian class members in comparison to white British students and described this as ‘an embodied colonial binary’? Can you say a bit more about what you mean by this and how you see it playing out?

Yes, I definitely saw important differences in the emotional responses of South Asian and white students to the course material and really had to think quite carefully about how to respond to this. On the one hand, South Asian students’ reactions to the material connected directly to some of the themes of the course about the ongoing legacies of Partition and so it felt like I would be completely undermining the course’s aims if I ignored it. On the other, I didn’t want to make these students exhibits for other students in the class to examine. This could clearly be very harmful for the students but also seemed to recreate age old colonial ideas about ‘emotional’ and ‘volatile’ South Asians in contrast to ‘rational’ white Britons.

We were unpacking this colonial thinking in the sources we were reading together but it was clear to me that this wasn’t only textual thinking, it was also an emotional and embodied logic. So I tried to draw out and foreground this within our class space too; I tried to create spaces in which South Asian students could reflect on how hard it was to read and learn about this history and its legacies, but in which white British students were also asked to reflect on why and how they were able to feel more emotionally detached from these events – even as they involved British people. One way we did this was to talk about how we saw ourselves reflected in the history we learned at school. In one very memorable class a British Pakistani student talked about ‘home history’ and ‘school history’ assuming this divide to be something all other students would understand and have experienced. This wasn’t the case for many British students. Discussing this together proved a really productive space to think about how learning shapes how we feel and not just what we know.

I think the assembly we’ve made can also be used to open up these kinds of conversations. Bringing personal, oral history through your aunt’s amazing testimony Iqbal, together with archival sources underscores that the official archive isn’t a neutral repository; it can’t tell us exactly what happened in August 1947, or what these events meant for the many people affected. Rather the archive shows us how the logic of Partition was built and sustained – how all the messiness of power and politics in late imperial India came to be explained and simplified into a narrative that saw Partition as not only a solution to India’s problems but as something that was even possible – dividing up land, communities, cultures that were intimately bound together at the level of high politics and everyday life.

Reading the archive this way ensures that we see imperial policy as absolutely fundamental to the story of Partition – as a way of thinking about the world that is still with us today, within wider British society as well as South Asian communities. But it’s also a hard and uncomfortable task and reminds us that white British people are also emotionally connected to these stories even if this isn’t how they are usually encouraged to feel about them.

Iqbal, can you say more about the making of the resource and the film and how it might connect with your own story?

Hannah, Eleanor and many others are aware of my own family background, which I have been open about. My father is Muslim and my mother is Sikh and they met on the ship coming here in 1960. What brought them together was their shared love of north Indian music but also something more, a link to a shared heritage that was seemingly forgotten.

I was struck, as an only child growing up in this unique family, that there was much division between communities that to all intents and purposes shared so much in common and that this narrative of division was also what so marked out the writing of this history.

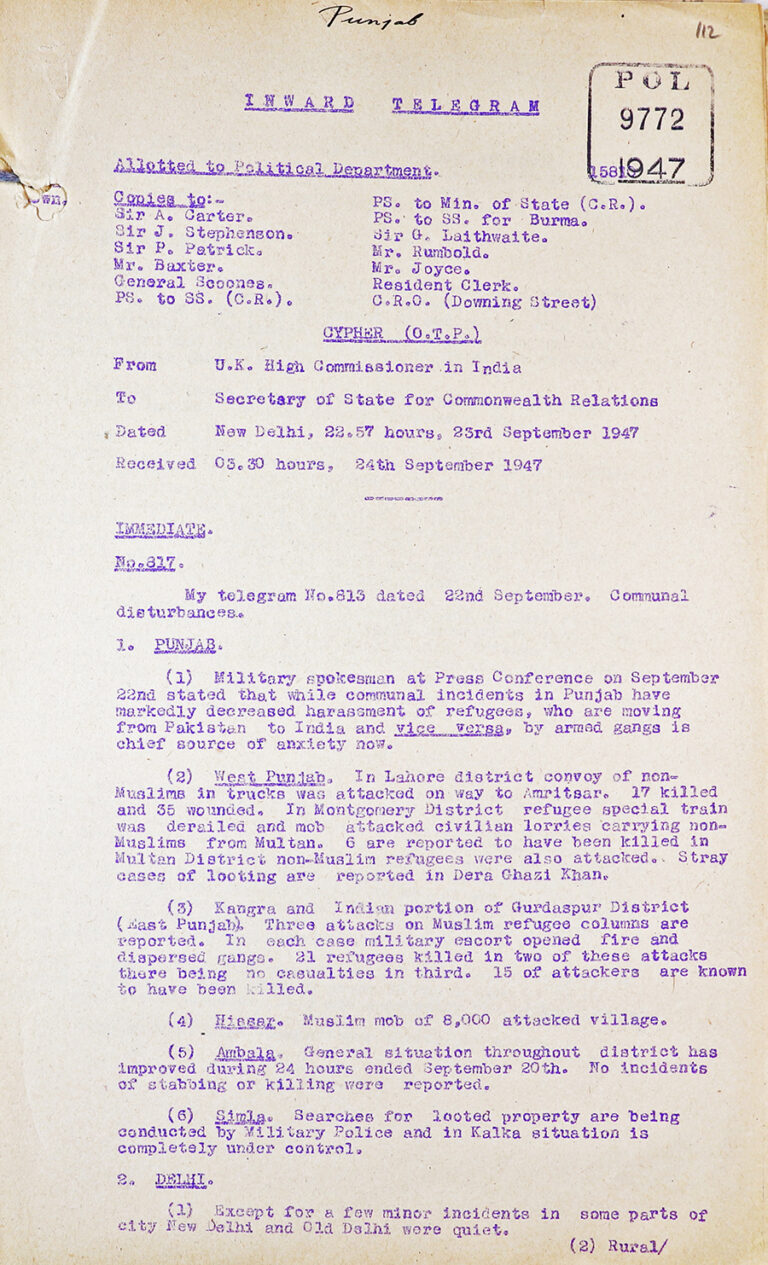

And that for me framed my interest in what we may explore through a teaching resource. So when Hannah chose the mystery document on ‘communal disturbances’ that forms the heart of our resource, I was happy she had done so.

So much of what is assumed or said about the topic is that it’s a simple division between two communities, Muslim and non-Muslim, and that it’s basically a religious conflict. I am constantly reminded by my own life story that much is hidden from this false and fatally simplified retelling of the Partition story.

The short film that is part of this teaching resource includes something of my story and recollections from my aunt, my mother’s younger sister, about Partition and what it meant for her (and my) family. And it brings home how the division was experienced, as she recalls her father’s longing for his ‘lost’ home in what had become Pakistan and how the evacuee property that my family took over in Dehra Dun (India) was actually the home of Mr Ansari who also was forced to leave.

Hannah, please tell us more about The National Archives’ approach to making such films and resources.

This film builds on our experience creating other online content, namely LGBTQ+ history in the archives, a film accompanied by a teaching resource. We collaborated with Bishopsgate Institute on this resource to provide a counterpoint to our official collection, as they are an archive that collects personal artefacts and documents. As with this partition resource we worked closely with Ellen Oredsson (Digital Projects Officer in Education and Outreach) who provided valuable guidance, filmed and edited the videos.

In this film we used a mystery document approach, thinking carefully about the document as an object. For instance, students were encouraged to consider the document code ‘DO’ which stands for ‘Dominion Office’, due to India and Pakistan’s new status as part of the Commonwealth. We analysed the language used on the cover of the file, Indian ‘independence day’ rather than partition. The telegram was selected because of its visual interest and relatively accessible provenance. The language used in the document provided a starting point to explore many themes relating to Partition. We also began to address the document’s position in the official archive, for instance highlighting the thickness of the file and what this could show about the enduring level of British concern in the region.

Iqbal, by way of conclusion, can you say something about what the key takeaways are from this project?

For me the takeaways are the same as those that we have outlined in the film. It is always important to remind ourselves that we are looking at documents at The National Archives here in the UK, while the Partition of British India happened nearly 5,000 miles away. Many British people don’t learn about this history but as we have seen this is a story in which Britain was a central player. It is important to learn about this topic through examining a variety of sources and official government documents are one very important source. But we need to be careful to unpick these documents. They may present as factual accounts, but this could be misleading. In October 1947 Lord Ismay, who had been closely involved in the Partition of British India, made the following comment: ‘the last two months have been so chaotic that it would be difficult to find two people who agree how the trouble started, why it was not checked, what actually happened, and what is to be the outcome.’ As students, teachers and historians we have many tasks, and Eleanor has so helpfully outlined some of these above, but somewhere our role is also to try to explain why British rule ended with this devastation, the largest mass migration event in history and the deaths of over one million people.

Further resources

- Partition of British India (classroom resource)

- Partition of British India (film – watch on YouTube)

- Decolonising the Partition of British India, 1947 (external site)

I would love to know if those creating this resource have watched the “take” on Partition (and “the British” ) presented by Disney MARVEL’s mini-series “Ms Marvel” on Disney+. That seems to be on where the “the British” are cast as only evil and seeking to “divide and rule” rather than address risks and requests raised by residents. It also avoids holistic discussion of India before the arrival of the British.

I was born in Allahabad on Dec. 3 1946. My Father & mother were both born in India & were of English decent. We left India in 1947 on a ship for Liverpool. I have always been very interested in knowing more about the partition and history behind the decisions. I now live in the USA .Thankyou for sharing this information.

Thanks for sharing valuable information. Please continue it.

Absolutely fascinating. An enormously important addition in curriculum development on Partition of South Asian sub- continent.

I very much appreciate the two exponents of this content,who carefully explain how who we are can then affect both what we know and how we understand it.