Last year we marked the 70th anniversary of the Partition of British India by highlighting existing resources and records from our collection which can help add to people’s understanding of this momentous event in world history.

We also undertook an Outreach programme that included teaming up with Bhuchar Boulevard and its touring theatre production of Sudha Bhuchar’s play ‘Child of the Divide’. In addition we worked with Let’s Go Yorkshire to engage regional audiences by co-hosting a creative writing workshop inspired by Partition records held at The National Archives.

You can read more about these creative projects in our blog post The Partition of British India: engaging new, diverse audiences

Visitors to The National Archives were fascinated and inspired by what we hold (image by Elliot Baxter Photography)

Controversial histories

Great controversy still surrounds the Partition of British India. Partition refers to the British transfer of power to two separate states – India (Hindu majority) and Pakistan (Muslim majority). It included the making of a Muslim homeland by partitioning the two provinces of Punjab and Bengal along Muslim and non-Muslim lines.

The histories that have been written, and the personal views of the historians who have researched the events of Partition, reflect levels of controversy that make it very difficult to write about what happened in a dispassionate or definitive way.

And the problem with writing about Partition goes much further and deeper than the personal and professional when one also considers how both nationalism and ‘community’ have shaped matters. As the historians Talbot and Singh observe:

‘It is important when addressing the growing and bewildering body of work on the subject to keep in mind that the compulsions of nation-building or community assertion have shaped historical writings, thereby producing selective histories and fragmented memories. Partition was more than a mere territorial division; it was foremost accompanied by a division of minds’.[ref]Talbot and Singh, ‘The Partition of India’ (2009), p8[/ref]

One of the numerous controversies that persists relates to whether the violence of Partition was unavoidable, and where the responsibility lies for the horror and extraordinary loss of human life that accompanied it, estimated to be anywhere in the region of 200,000 to 2 million.[ref]The number of deaths resulting from Partition also remains a disputed figure, see Talbot and Singh (2009), p2[/ref]

Following the announcement of the boundaries separating the two new nation-states of India and Pakistan, there was a massive exchange of populations and a very significant loss of life. In the Punjab which, alongside Bengal, was most affected, there continues to be much disagreement about who knew what and what their roles were.

R J Moore, writing in the early 1980s, said that it is impossible to resist the argument that the Punjab massacres were a concomitant of partition, as unavoidable as the migration of the Sikhs to re-establish themselves in the East.[ref]R J Moore, ‘Escape from Empire’ (1983), p331[/ref]

E W R Lumby, writing some years earlier, said it would be ‘difficult to resist the conclusion that the British Government and Lord Mountbatten should have insisted to the utmost of their power that the two new Governments must accept a modicum of British control in the areas of worst danger until these had had time to adapt themselves to the new conditions of life’.[ref]E W R Lumby, ‘The Transfer of Power in India’ (1954), p265[/ref]

Dual heritage

What is inescapable is the very personal cost that many millions paid as a result of Partition and the ways their lives were shaped by it. My mother was 11 when Partition started. Her family, who were non-Muslims (Sikh), had safely made the transition from their home in Rawalpindi (Pakistan) to Dehra Dun (India) in 1946. She can still recall the violence of the time; it still upsets her greatly. My father, aged 16, from a Muslim family, was studying in Allahabad (India) at the time of Partition; he was recalled by his father to a Muslim majority town as a precaution before leaving in the mid-1950s to go and live in Pakistan.

Both my parents were among the lucky ones, unlike many millions caught in the borderlands, towns and cities where the exodus across a still-fragile border took place.

I have lived with this dual heritage, aware from a very young age of the divide between people who in so many respects were extraordinarily similar. Therefore the opportunity to mark this very important anniversary has meant a lot to me.

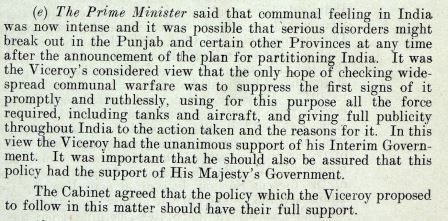

My mother’s sketch: reflection on Partition after seeing, many years later, the keys to the home she had left in Rawalpindi (now Pakistan)

Plan to Partition

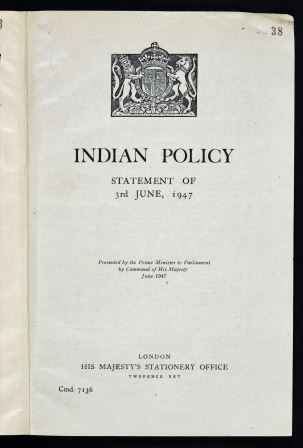

Our collection focuses on the high politics of Partition, including both the lead up to Partition and its fallout. The plan to partition British India was endorsed at a meeting of the British Cabinet in May 1947 and announced in the British Parliament on 3 June. The Cabinet agreed with the Viceroy’s view that:

‘The only hope of checking widespread communal warfare was to supress the first signs of it promptly and ruthlessly, using for this purpose all the force required, including tanks and aircraft, and giving full publicity throughout India to the action taken and the reasons for it.’

Cabinet Minutes, 23 May 1947 (catalogue reference: CAB 128/10)

The plan came at the end of a long period of negotiations to find a way to keep India united. A 1946 Cabinet Mission headed by three senior British representatives aimed to find a workable compromise. It had been preceded by a previous British government mission led by Sir Stafford Cripps in 1942. The 1946 Cabinet Mission sought to secure agreement that would allow power to be distributed between an All-India Union government and the provinces. The ultimate failure of the mission provided the catalyst for the decision to transfer power.

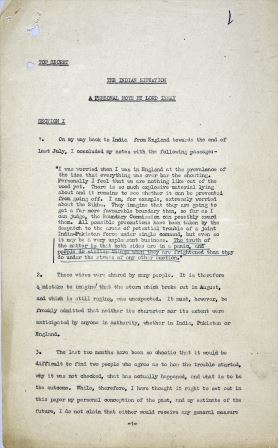

The plan to partition was delivered to the UK Parliament on 3 June 1947, the same day it was announced in India (catalogue reference: PREM 8/541/10)

The June plan was approved with the express caveat that robust action would need to be taken to stop excessive communal violence. Here, once again, controversy exists, with the historian Alex von Tunzelmann arguing that Nehru had made unequivocal his opinion that British troops should not remain in India a moment longer than necessary:

‘The situation was unambiguous: the British government, the British services and the Indian government all insisted that British troops should be removed from India at the earliest opportunity. It is fanciful to imagine that Mountbatten could have acted in direct contradiction of the wishes of all three of these bodies.’[ref]Alex von Tunzelmann, ‘Indian Summer’ (2007), p255[/ref]

By contrast, the historian Yasmin Khan argues that, despite numerous warnings coupled with recognition at how explosive the situation had become, both the plan for partition and its implementation were very flawed.[ref]Yasmin Khan, ‘The Great Partition’ (2007), p102, p208[/ref]

Unresolved disputes

In the immediate aftermath of Partition the two new states sought to settle disputes on a whole host of areas, including what each owed the other for those who had been displaced as evacuees. India claimed that property left by Indians in Pakistan was worth three times that of those who left to settle in Pakistan. Pakistan claimed that the property left by those coming to settle in Pakistan had been heavily undervalued by India.

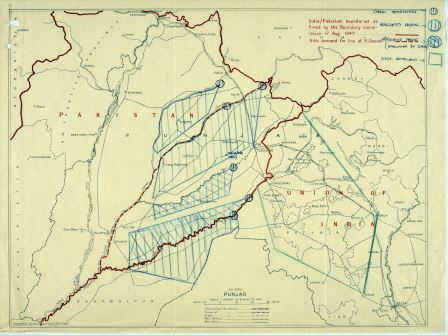

- Evacuee property booklet, 1950 (catalogue reference: DO 35/2994)

- Evacuee property booklet, 1950 (catalogue reference: DO 35/2994)

Lord Ismay (Chief of the Viceroy’s Staff), reflecting on the fallout from Partition in October 1947, captured some of the overwhelming nature of what followed:

‘The last two months have been so chaotic that it would be difficult to find two people who agree as to how the trouble started, why it was not checked, what has actually happened, and what is to be the outcome.’

His observations continue to shape the disagreements in how Partition is written about and discussed.

‘The Indian Situation’ by Lord Ismay (catalogue reference: DO 121/69)

Was the violence unavoidable? Or was there something the British Government and Mountbatten could have done to mitigate the level of violence and killing? Was Nehru at fault by demanding that British troops leave India at the earliest opportunity? Did this contribute to the violence being so excessive? Or was it unfair to expect nascent governments that had just emerged as newly independent nation-states to take on such a mammoth administrative and political task?[ref]Yasmin Khan, ‘The Great Partition’ (2007), p103[/ref]

These are just some of the questions raised about the violence and loss of life that followed the decision to Partition British India.

India and Pakistan map highlighting on-going disputes about borders, Oct 1947 (catalogue reference: DO 121/69)

This most interesting. Having read a few books on Partition, and what happened, one must blame both sides for their administrative and political carelessnesss not to have made a peaceful transition.

Nehru and his colleagues perhaps did not have enough experience to foresee the horrors that took place in parting the country. Most of all, The British who had so much control over India for 200 years, could have controlled the situation even then and insisted on assuring a peaceful transition. Was it not the British who encouraged and sided with Jinnah to get a country for the Muslims? Did they not have their own political interests in mind? Did they not hope for chaos so they would be asked to stay on to rule? This Partition makes no sense to this day, same race of people with the same roots, same culture, living in relative peace were forcefully torn apart. There are more Muslims in India than in Pakistan to this day.