This blog post is part of 20sStreets, in which we explore local history stories in the 1921 Census, connecting people of the 2020s with people of the 1920s. Discover your own local history and enter our 20sStreets competition.

In August 1921, just two months after the return of the 1921 Census of England and Wales, British parliamentarians deliberated on the legitimacy of same-sex relations between women and whether such relationships or physical acts should be criminalised as part of the 1921 Criminal Law Amendment Act. Despite concerns among moralists, legislation was not changed. Many MPs, including the Lord Chancellor, argued that ‘the overwhelming majority of women of this country have never heard of this thing at all’[1], while others argued that an amendment would in fact provide unwanted visibility.

And yet, records from the 1921 Census provide insight into the lives and relationships of LGBTQ+ individuals in the early 1900s, in particular the domestic lives of women in same-sex relationships. As Diverse Histories Specialist, Vicky Iglikowski-Broad notes in her blog post LGBTQ+ lives through the census, ‘while the language has changed, LGBTQ+ people have always existed. Their stories can be found on the enumeration sheets of the census, just as everyone else’s can’.

This blog post will discuss what we can learn about the lives of notable LGBTQ+ figures Radclyffe Hall, Una Troubridge, Edy Craig, Christopher St John and Tony Atwood. We will see where they were recorded as living in 1921, and their move out of the city to Kent or Sussex, at the end of the decade. Not only highlighting the existence of same-sex relationships and non-normative identities during the 1900s, but also LGBTQ+ experiences outside of the capital city.

LGBTQ+ life in the city

Much of what we know about queer historical lives – as recorded in the census and more broadly when researching within the archive – tends to centre on life in the city and in particular LGBTQ+ life in London. As explored in our 20sPeople season and exhibition Beyond the Roar, London in the 1920s was an environment of social change. As a result authors, artists, performers and those that identified at LGBTQ+ appear to have been drawn to the city.

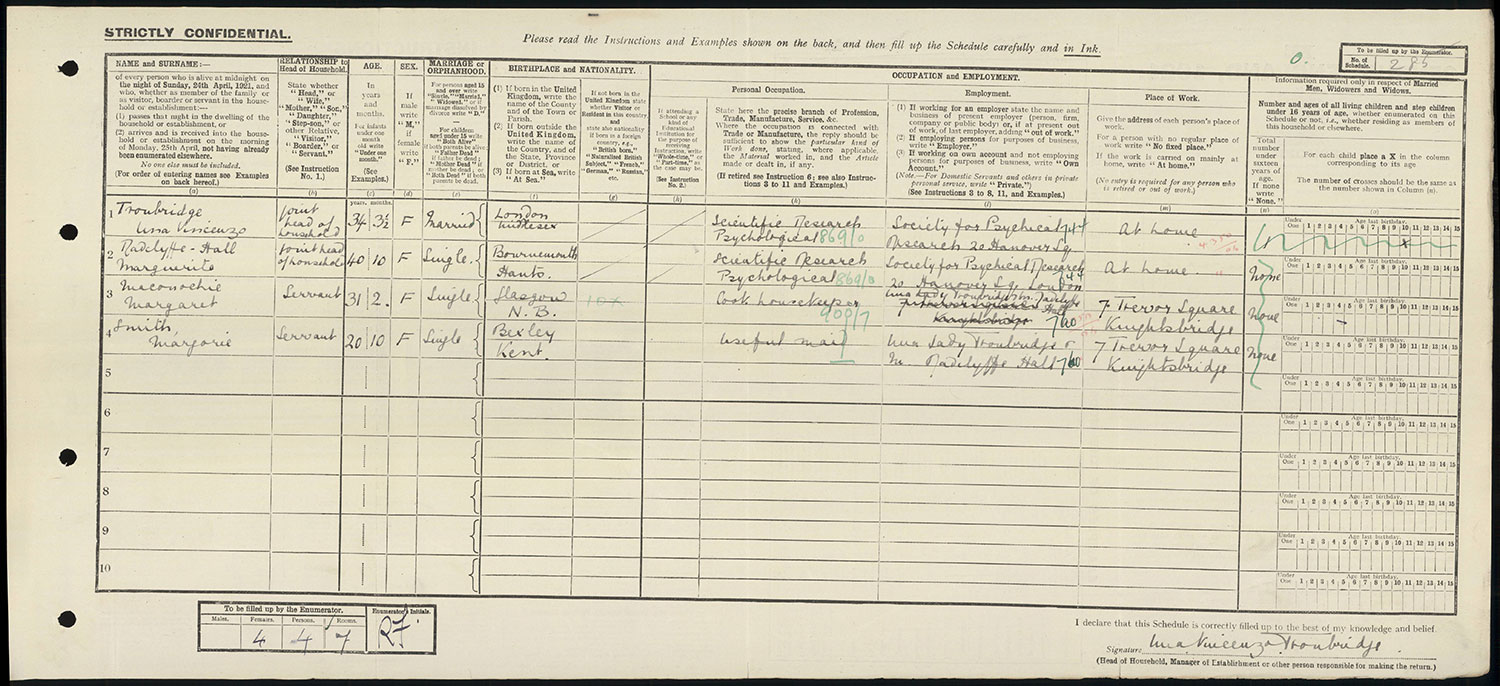

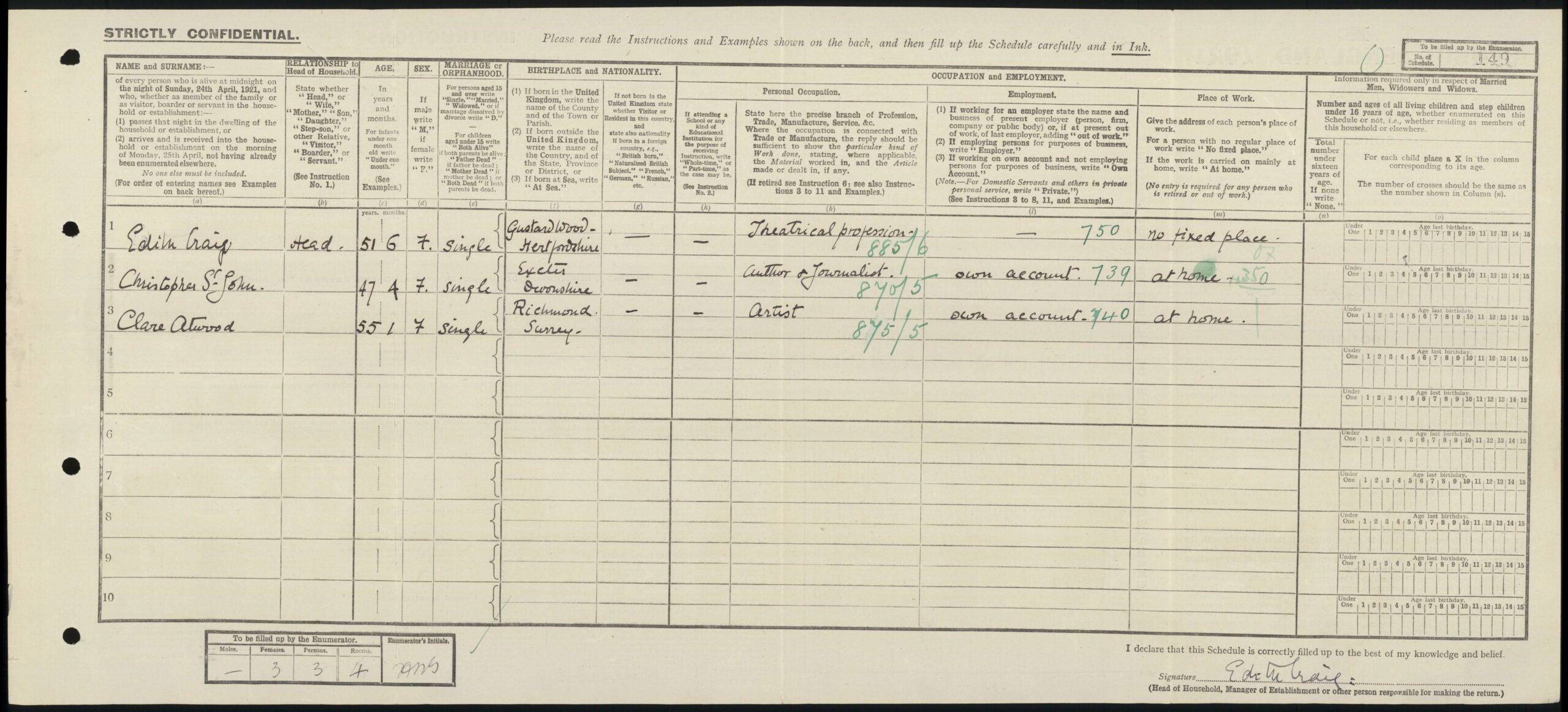

For example, Census records show that in 1921 author Radclyffe Hall and the artist Una Troubridge were living together in London, at 7 Trevor Square in Knightsbridge. Similarly, the lesbian ménage à trois of theatrical director Edy (christened Edith) Craig, author Christopher St John [2] and artist Tony Atwood [3] are also recorded as living together at 31 Bedford Street, Covent Garden.

And yet, despite the significance of the city for creatives and queer people alike (see also blogs on queer networks and letters between men, Billie’s Club and The Link lonely hearts publication), many LGBTQ+ individuals sought refuge in the English countryside. In fact, as this blog post explores, a small community of queer creatives including Hall, Troubridge and Craig, exchanged life in London for rural living in Kent and Sussex.

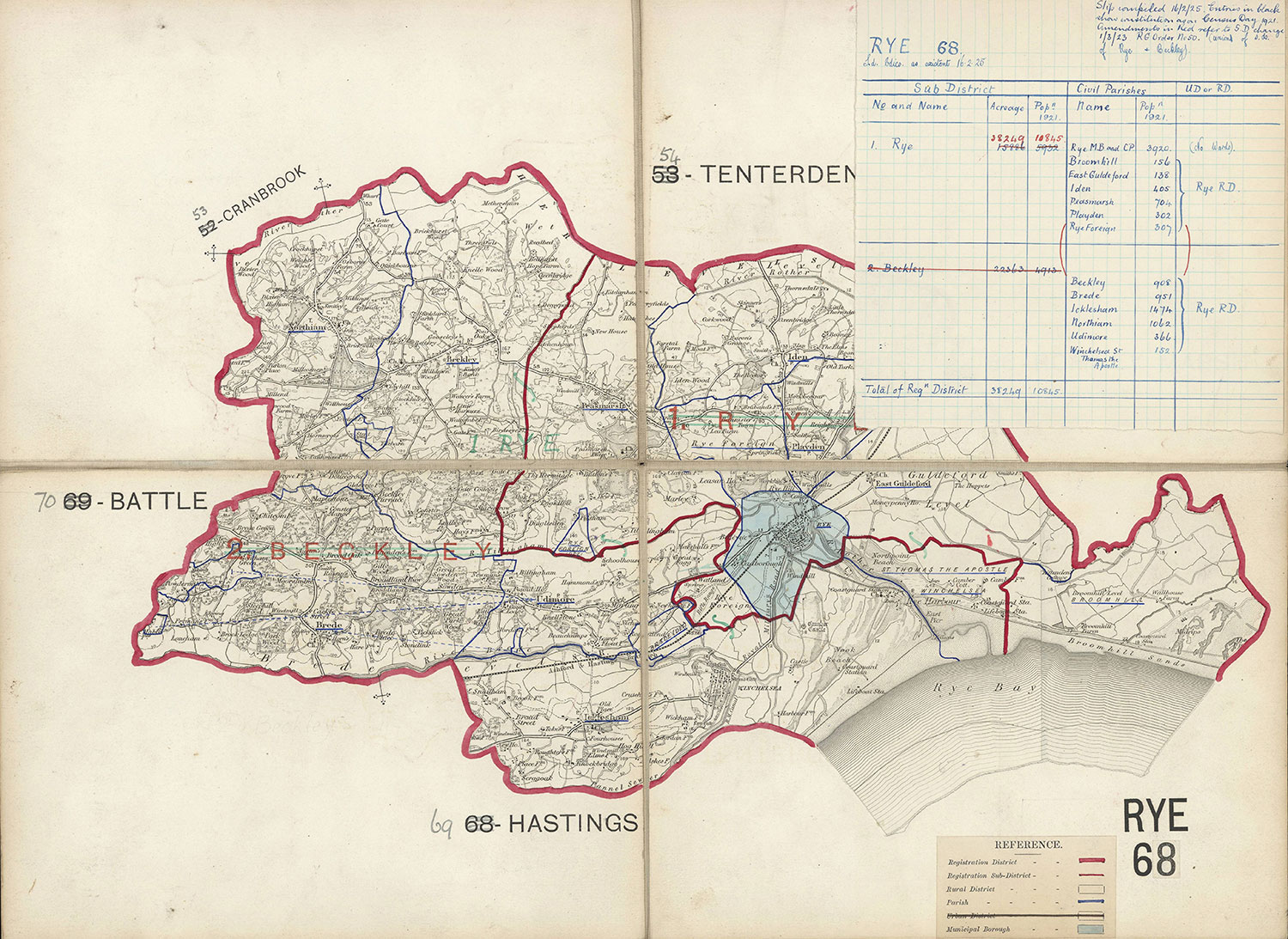

Refuge in Rye

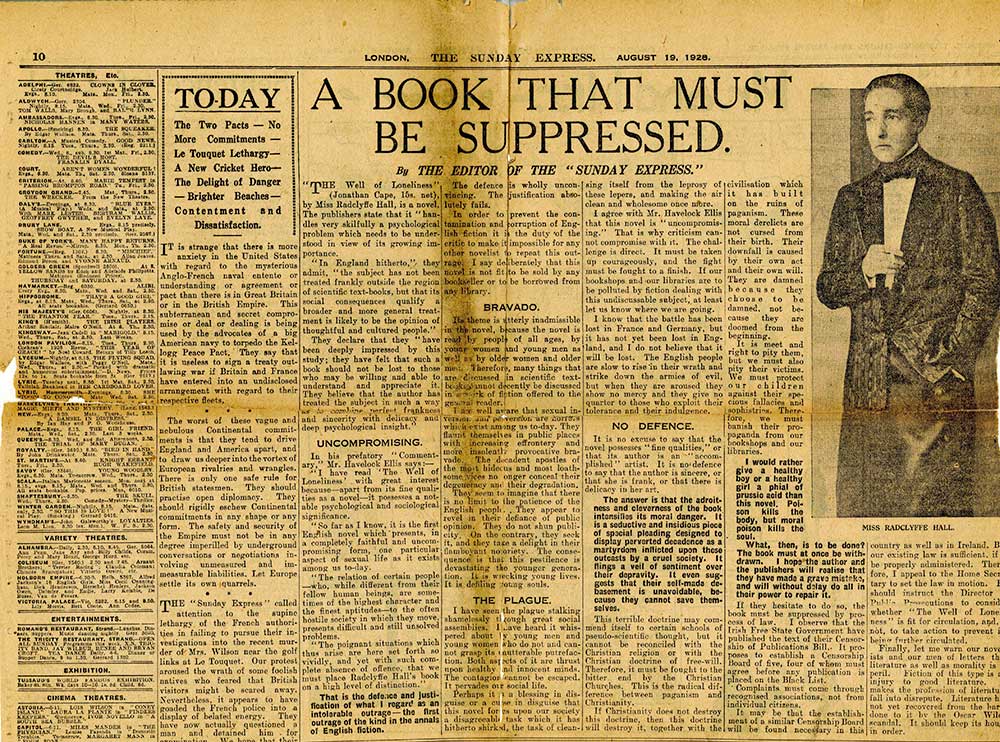

At the end of the 1920s, following the publication of her infamous lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness and the public obscenity trial that followed, Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge sought to escape the intensity of city life in favour of coastal living, finding solace in the coastal town of Rye, East Sussex.

In her biography of Hall, Diana Souhami writes that the two ‘hunted for a house away from the squalls of city life’ choosing Rye as the location for their new home. [4]

Souhami elaborates that Hall ‘was thrilled by the views of marshland and the sea, the distant lighthouse and the glimpse of France, the cobbled streets and Tudor architecture … and resolved to buy a house [there]’. [5]

Rye became a refuge for Hall and Troubridge from the 1920s onwards; throughout the tumultuous obscenity trial which saw Hall’s lesbian novel prosecuted and banned, until the later years of the couple’s life.

Troubridge herself wrote that Rye was ‘a heavenly haven of peace in which we pulled ourselves together for the next round’, and Hall captures the beauty of the area in her 1936 novel The Sixth Beatitude. [6]

Edy and the Boys

While the 1921 Census shows that Edy Craig and partners Christoper St John and Tony Atwood were living together in Covent Garden, the trio similarly moved between London and Kent. Troubridge recalls visiting ‘Edy and the boys’ and enjoying ‘monthly bar shows, with soliloquies and sandwiches’ with them at their residence in nearby Tenterden. [7]

Edy had a strong and long-lasting relationship with the 16th-century estate Smallhythe Place which was initially owned by her mother, famous actress Ellen Terry. From 1899 Craig and St John lived periodically in a home on the grounds of Smallhythe called ‘Priest’s House’, where they were later joined by Atwood to complete their ménage à trois.

Following the death of Ellen Terry in 1928, Craig committed herself to celebrating both the history of Smallhythe Place and her mother’s career, transforming the home into a museum. Smallhythe is currently preserved by The National Trust, who endeavour to keep Terry and Craig’s legacy ‘alive today with a diverse programme of productions in the theatre and garden that are performed throughout the year’. [8]

A queer rural retreat

In addition to hosting Troubridge and Hall, The National Trust notes that ‘Smallhythe was visited by many other queer women including Virginia Woolf and her lover Vita Sackville-West, who lived at nearby Sissinghurst’. And the list of notable LGBTQ+ figures in the South East does not end there.

Other LGBTQ+ figures and icons that lived in Kent and Sussex at the turn of the century include the novelist E. F. Benson, as well as singer and musician Lady Maud Warrender with her lover Marcia Van Dresser, also in Rye.

Souhami claims that ‘In Rye, as in Paris and London, Radclyffe Hall was drawn to the artistic lesbian and gay coterie gathered there’. Thus, while London is often the central focus when researching LGBTQ+ lives, the significance of Kent and Sussex as rural retreats for notable queer figures cannot be ignored.

Footnotes

1. Commons Amendment, vol 43: debated on Monday 15 August 1928.

2. Christopher St John née: Christabel Marshall. St John was the pen name and later legal name for Marshall. Given that this was also the name that they gave in the 1921 Census, this is the name I will use throughout.

3. Tony is the name adopted by Atwood (christened Clare), which I will use throughout.

4. The Trials of Radclyffe Hall, Diana Souhami (Doubleday, 1999)

5. Dr Richard Omrod provides further insight into the properties rented and owned by the couple during this time.

6. The Life and Death of Radclyffe Hall, Lady Una Troubridge (Hammond and Hammond, 1961)

7. The Trials of Radclyffe Hall, Diana Souhami (Doubleday, 1999)

8. Smallhythe Place | Kent | National Trust

A great article about some amazing women (but just wanted to point out that Rye is in East Sussex)

Whilst it does not detract from the article in any way, it would have been better to get the geography correct.

Thanks, very interesting. Small Hythe is well worth a visit if nearby.

The article was very interesting.

I am appalled however to see that the National Archives has moved Rye from Sussex to Kent. As the error occurs several times it cannot be a typographical mistake.

On behalf of all Sussex Yeomen, I trust a correction will be made without delay.

We seem nowadays to be too much concerned with people’s sex lives and although lesbian relationships were by no means unknown it must be remembered be that many women probably cohabited for economic reasons and companionship due to the acute shortage of men following the First World War

Fascinating! Please do have a look at our linked entries on the Smallhythe trio at

https://www.kent-maps.online/20c/20c-craig-biography

https://www.kent-maps.online/20c/20c-st-john-biography

Rye is NOT in Kent but rather is in Sussex.

Oh, National Archives! How could you make such a mistake?

Your history may be good but geography does not appear to be a strong point.

Rye is in Sussex not Kent.