‘I just want to be with your arms round me and soak myself in the atmosphere of contentment.’

Line from a letter from Eric to Bert (CRIM 1/387) 1

This line reads like one from any love letter, from any time period. It displays openly love, joy and affection. And yet this quote is from a love letter between two men from the 1920s. Even writing these words down was potentially incriminating.

The line is from one of nine letters and a Christmas card that were found in a raid on 25 Fitzroy Square, London. The basement flat was home to Bobby, where he would hold parties for a small group of his working class friends. It was raided in 1927 under accusations of being a disorderly house. You can find out more about these gatherings in the first part of this blog.

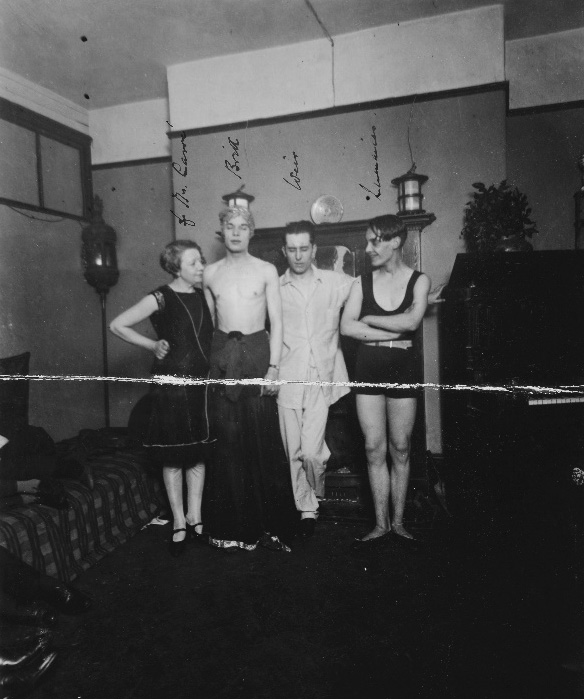

These letters were written to Bobby and Bert, who were both present during the raid. (In the photograph Bobby is wearing the long skirt and is bare-chested; Bert is wearing the swimming costume). Bert was the nephew of Bobby, and said to police that he often stayed at the Fitzrovia flat at weekends. Both were dancers and Bobby was teaching Bert; they would perform salacious dances to their circle of friends at these gatherings.

During the raid on the venue, their letters were seized as potential evidence, alongside the photographs and other items. Despite the reason they were kept, these wonderful letters can tell us huge amounts about the queer community and LGBTQ+ networks at the time. They reflect many different emotions: reciprocated and unreciprocated love; romance and friendship between men; and navigating a queer identity in an era that essentially criminalised your love.

‘My dearest camping Bessie’

These letters don’t just tell us about love, but also about queer friendships and international networks. One of Bobby’s friends, Macnamara (we aren’t given his first name), had not long moved to America:

‘However we can still write to each other in sincere friendship and when I come back you’ll be the first I come and see.’

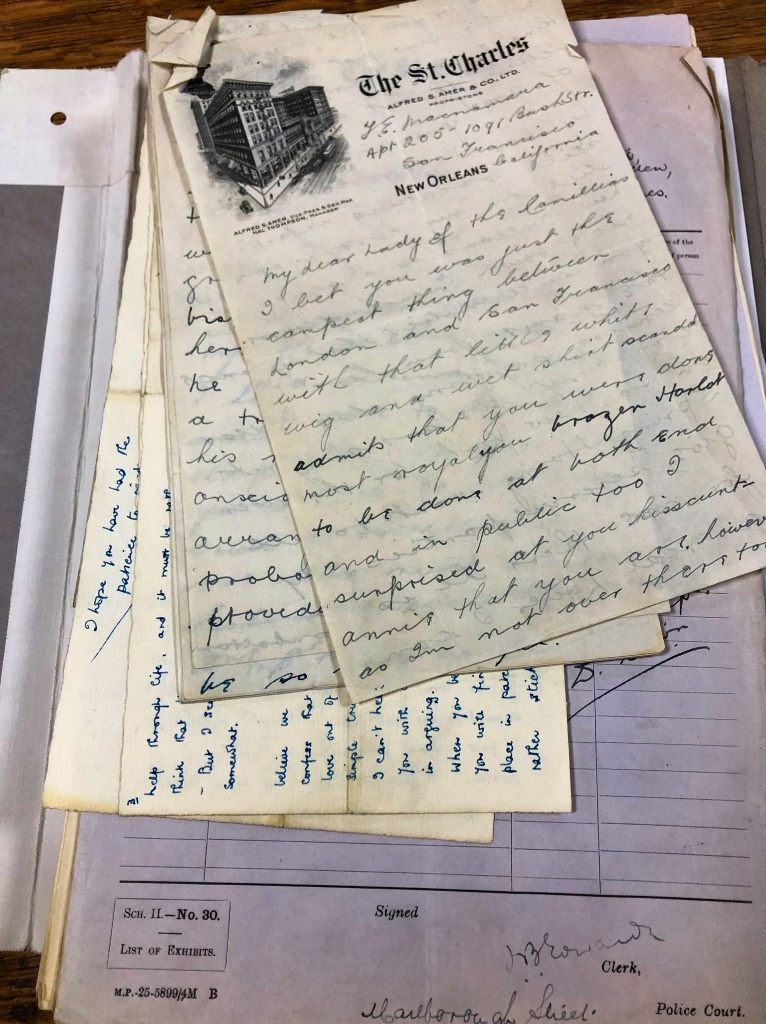

Macnamara’s letters give some fascinating details about their lives. They are filled with wonderful, affectionate nicknames, queer humour (at times wonderfully lewd!) and an underlying love and companionship between friends, that stretches across the Atlantic.

The letters start from the time of Macnamara’s initial journey and arrival in America in 1922. He described his life prior to this as being one of ‘a poor working harlot from the streets of London’. On the boat ride to the States Macnamara describes the swing dances every night and how he was a ‘great hit’ at the fancy dress ball wearing a red bed quilt and fan behind his head. Following this the police underline any reference to gender (‘two real women’, ‘man’, ‘manly’). While writing these letters he is travelling extensively, mentioning San Francisco, New Orleans, California, and at one point describing his dear Bobby as ‘the campest thing between London and San Francisco’.

One of the most revealing parts of these letters is the relationship Macnamara develops in America, using many phrases associated with heterosexual marriage, such as ‘pet husband’, ‘marriage’ and ‘honeymoon’. Despite this being many decades before same sex marriage was legalised, they were still conceptualising their relationship in these terms 2. He described his partner Harry as ‘a real lover’ but also calls him jealous and stubborn; Harry ‘won’t let me go to work, it is really dreadful as I [am] cultivating such extravagant tastes’.

One of the stand out things from these letters is the wonderfully flamboyant terms of address the pair use towards each other, such as ‘Lady of the Camellias’, ‘My dearest camping Bessie’, ‘you brazen harlot’ and ‘old auntie Aggy’. An obvious campness and humour shines through. Of all the police’s underlinings the mentions of alternative gender expression get the most attention, with Macnamara writing to Bobby phrases such as ‘My dear sister, one day, you must come over’ and the wonderful sign off:

‘Yours as ever Your old drunken Auntie Elizabeth

Kisses and kind thoughts to Sister Nellie’

After these letters were seized Bobby was sentenced to 15 months hard labour. What would Macnamara think about the lack of letters? Did he find out about Bobby’s arrest through other friends and networks? How would this kind of treatment differ from Macnamara’s experiences in America?

Queer clubs and spaces

A theme in several of the letters to Bert and Bobby is the queer scene in London and the rich possibilities of socialising that 1920s London offered, which went significantly beyond their gatherings at Fitzroy Square. Leslie Kinder appears to write to Bobby from Brixton Prison following his imprisonment after the raid on the Adelphi rooms (as a 26-year-old waiter) 3. He had been sentenced to 21 months hard labour. This emphasises the links, networks and friendships between these spaces.

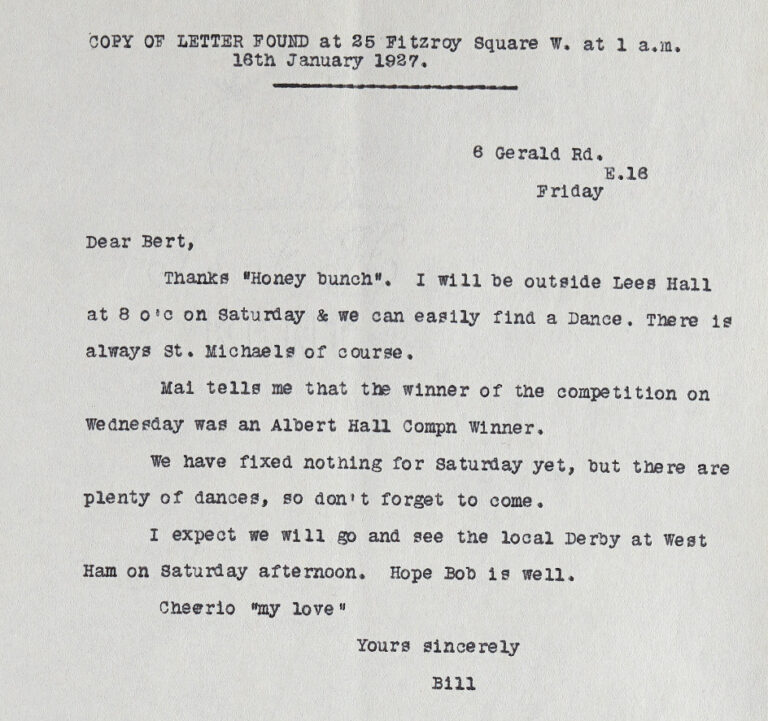

In another letter from Bill to Bert ‘honey bunch’, the pair are looking to meet and go out. Bill states they ‘can easily find a dance’ and there are ‘plenty of dances, so don’t forget to come’, suggesting a thriving gay scene at this time, despite the underground nature of it. The two very different references in the letters demonstrate the risks and opportunities these spaces offered at the time.

‘Oh I do love you …’

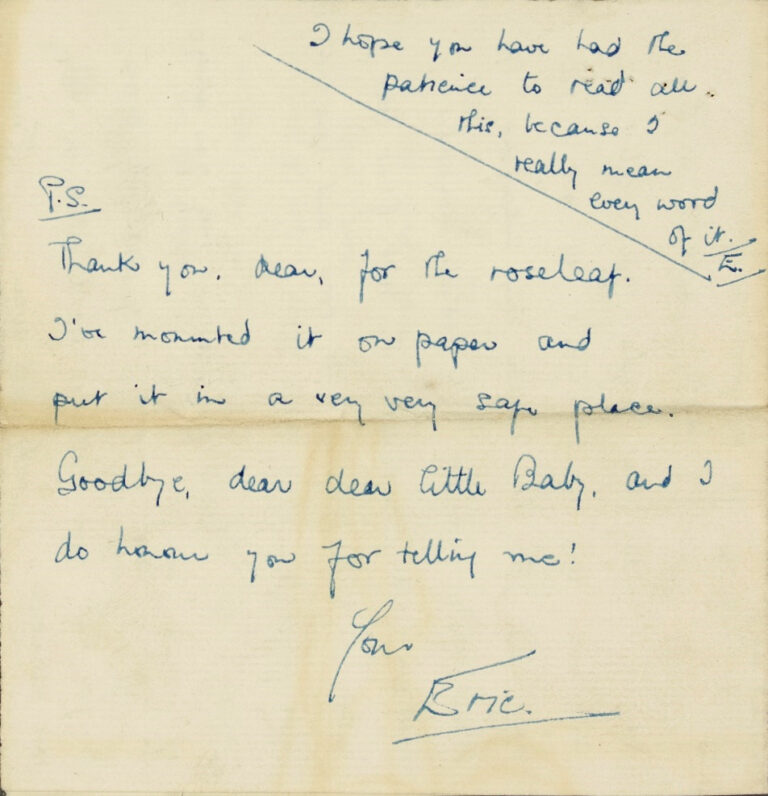

The seized letters addressed to Bert are predominantly love letters, but they show the complexities of love between men, including love that had to be hidden and unrequited love. One letter from Eric is written in several stages at different points in the day (the location is noted to change throughout, being written ‘In the office’, ‘at lunch’), and is an intense, heartfelt expression of someone in love but not being loved back.

‘You say that you could never love me, – but that you offer me friendship, which you say is far greater than love. I cannot agree with you about this my dear . . . I must confess that I don’t see how I can keep love out of my side of the friendship. It is a simple true fact that I love you baby dear.’

Eric to Bert, 1927 (CRIM 1/387)

The letter is lengthy and passionate. Eric writes to Bert, ‘I have an intense desire to make you happy – I worship the beauty of your body, and your dear, dear face and hair, and eyes, and I want to hold you very close to me.’ However, it seems that Bert only wants friendship. As Eric writes, ‘we are all foolish sometimes’ when it comes to matters of the heart.

A letter sent after this date seems to be between Eric and ‘Peter’ (who may also be Bert and was certainly interpreted to be by police). This letter talks of the frustration of not being able to talk publicly about their feelings: ‘I wanted to shout to the whole of the office that I was in love with you’. This underlines that while relationships were possible between men, they often had to be secretive, and hidden from work and family. In these letters, police have taken time to underline male names, male pronouns and phrases that demonstrate romantic love.

The nature of having records because of the raid means we only have one side of the conversations. This leaves us with many questions. How did Bert really feel about his heartbroken correspondent? What was Bobby writing in his return letters about his life in London? Maybe they spoke about the gatherings he held at Fitzroy Square? Maybe they spoke of his excitement of performing on the stage in ‘Lady Be Good’?

Use as evidence

The versions of the letters held in The National Archives are both handwritten and typed. The police indicated the sections they found particularly concerning by underlining them in green and red. Even the forms of address and sign off could be problematic in the eyes of law – affectionate nicknames could become a coded sign of homosexuality or transgression when written between men: ‘My dear baby’, ‘Always just Eric x’, ‘Peter darling’ and ‘Well now honey love’.

Although we have these letters preserved in our collections, it seems ultimately they were not used as evidence in court. Newspaper reports show Sir Henry Curtis Bennett, K.C. believed they ‘ought never to have been admitted as evidence, as they could not be properly connected with the offence with which appellants were charged’ and would lead to a natural prejudice against those brought to court. After all the letters were not directly connected to the charge in question, of a disorderly house, and some pre-dated the raid by several years. Sir Henry did concede that the letters were clearly of an ‘obscene character’ 4. The use of photographs in court were considered similarly controversial, as they were arranged rather than capturing directly what was seen by officers on arrival 5.

Although the letters were dismissed as evidence in court, Bobby received a sentence of 15 months hard labour, Bert eight months in the second division.

Queer networks continue . . .

These letters are wonderful to read, showing the vibrant potential of love between men in this era; the heartbreak, the socialising and the wonderful friendships. But there is also a sadness that we even have these records at all, that the love and friendships of these men was ever policed. The presence of these love letters in the police files demonstrates the very real danger of writing about queer desire in the 1920s. They now provide us with a rare personal insight in to queer lives in the early 20th century.

Records show that not long after their prison sentences, in 1929, both Bobby and Bert travelled to New York. Maybe it is a wistful dream of mine but I like to think they got to visit Macnamara and his husband, travelled the States and continued to develop their wonderful queer friendships.

Notes:

- This blog post is based predominantly on the Central Criminal Court depositions in CRIM 1/387. ↩

- Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act 2013. ↩

- Houlbrook, Matt, Queer London, Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918-1957. 2006. p. 90. ↩

- ‘Photographs Taken By Police. Men’s Fancy Costumes In Flat Incident’ article in Reynolds’s Newspaper, Sunday 27 March 1927. British Newspaper Archive. ↩

- ‘Photographs Taken By Police.’ Reynolds’s Newspaper, 27 March 1927. ↩