This blog post is part of 20sStreets, in which we explore local history stories in the 1921 Census, connecting people of the 2020s with people of the 1920s. Discover your own local history and enter our 20sStreets competition.

The First World War unleashed a significant ‘anti-alien’ backlash, focused initially on Germans living in Britain. This led to the passing of the Alien’s Restrictions Act 1914 within days of the war starting. As the war progressed, the pressure to treat ‘coloured’ men from Britain’s empire as aliens mounted. Men from what today is known as Yemen, but also other parts of the empire, had been coming to Britain in search of employment from before the start of the war, in the knowledge that they could secure more profitable work by working from British ports. Many had settled in port cities like Cardiff, making new lives there. The more enterprising set themselves up as local boarding house masters, providing accommodation to meet the needs of itinerant sailors. It is worth noting that, of the total number of men employed on British ships during the interwar period, over one quarter were foreign seamen.

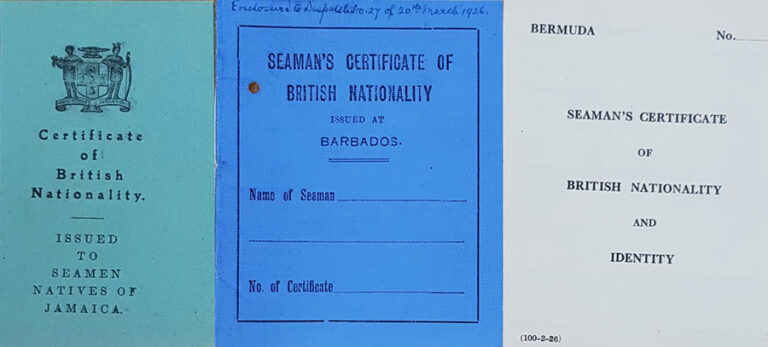

The 1920s saw matters change, maybe most significantly with the passing of the Special Restriction (Coloured Alien Seaman) Order in 1925. This required men to register regardless of their claims to be part of the British Empire. By way of compromise, new certificates of nationality were issued to them; it’s from these records in our collection that we can start to piece together something of their life stories here in Britain. We often see the same addresses repeated in forms, suggesting it was a boarding house, and Cardiff addresses appeared frequently. The recent release of the 1921 Census backs this up; for the centenary I researched one of the seafarers-turned-boarding housekeeper, Said Mohamed, and the entry for his home in Cardiff includes countless entries for men from around the world.

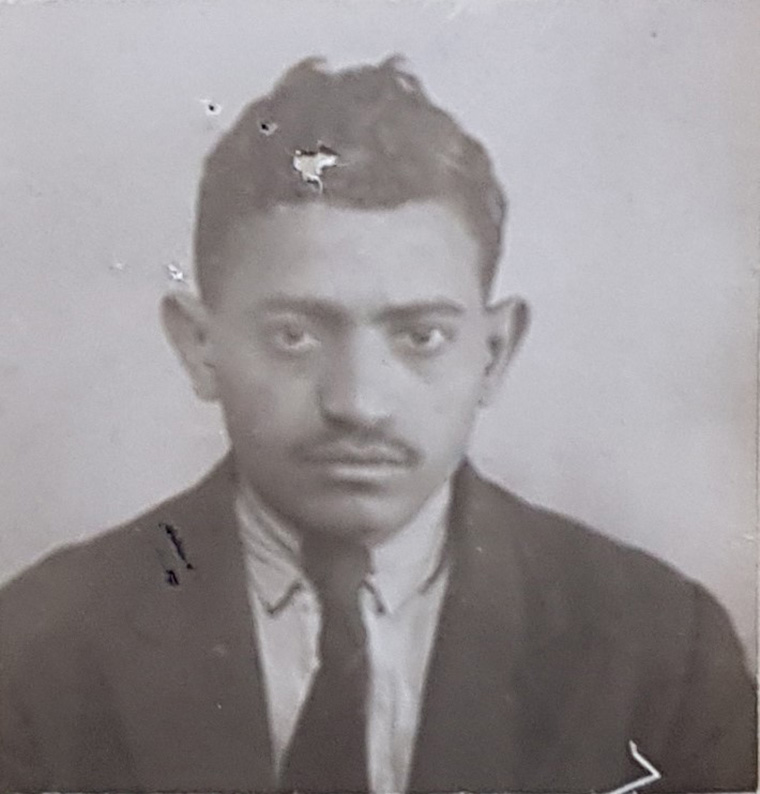

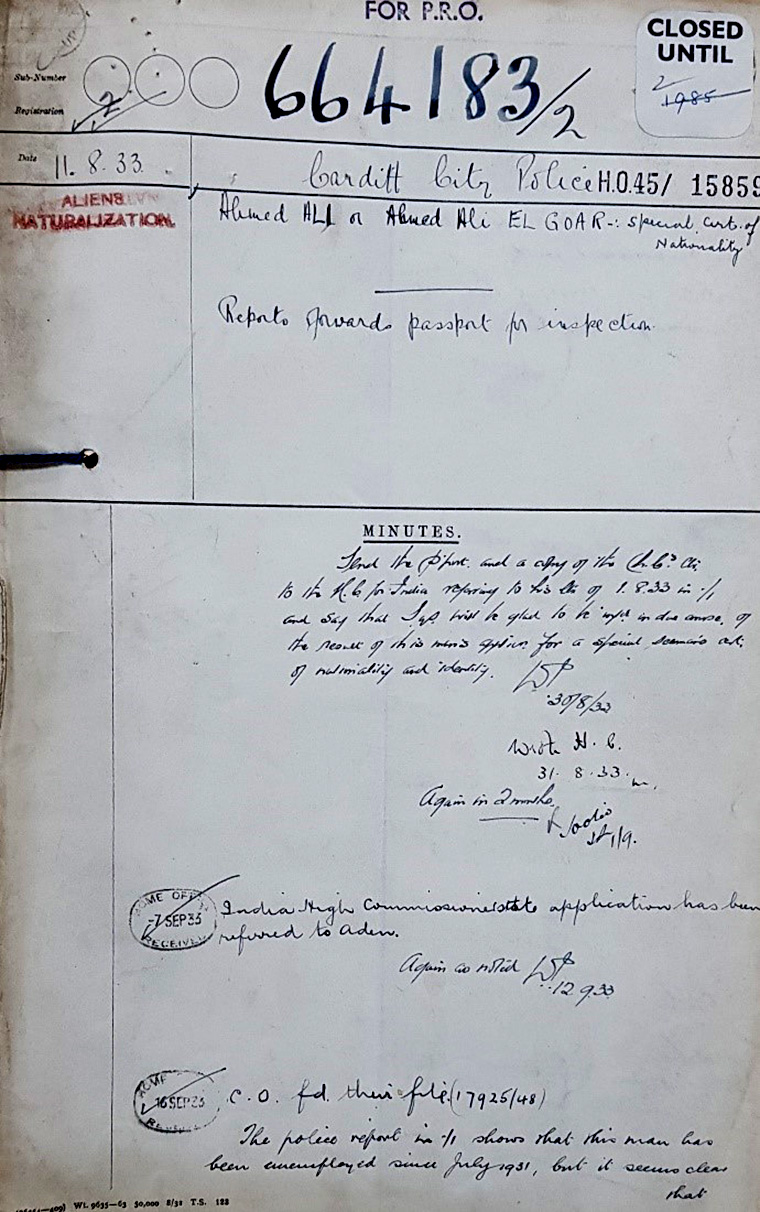

The case of Ahmed Ali Goar is instructive of the debates that were very active as to who could call themselves British or not. We first encounter Goar when he appears in a Cardiff police report in 1933, having been admitted into the City Lodge (Public Assistance) Hospital. He was in possession of a passport, valid for five years, which was approaching expiry. The passport said that he was a British Protected Person and that his place of birth was Aden. On arriving at a British port some years earlier, he had been instructed to register with the police and was now asked why he had not done so earlier. He replied that no verbal instruction was given to him and, as he could not read or write English, he was not aware of any endorsements.

We then learn a little more about Goar, who says he is 37 and worked in a bake house in Aden until 1927. He then proceeded to Marseilles for employment, where he got his passport. In France he says he was told by officials that as he was a British subject, he needed to make his way to Britain, so at the end of the 1920s he sailed to Southampton. On arrival, Goar claimed to be a British subject and was advised to apply via the Indian High Commission (which was overseeing cases of men from Aden) for a right to stay here.

Enquiries made by officials revealed that Goar was in fact a native of Riashiya in Yemen and subject of the Imam of Sana. Therefore, he was deemed neither a British subject nor a British Protected Person and thus his right to be in Britain was considered questionable.

At this point in the file, we lose trace of his story. However, what is known from other similar cases is that this is not too dissimilar to other men who entered Britain assuming they were British, and in the new interwar regimes of mobility control, found themselves feeling like outcasts.

Goar’s case highlights how men’s claims to be from Aden and therefore a British subject became increasingly suspect in the interwar period. Home Office records of a meeting to discuss colonial seafarers in 1923 said that ‘Arabs could be divided into three categories’ of whom the most concern was for those termed ‘purely alien Arabs’, who could neither claim subject status or say they were from a British protectorate (HO45/11897).

It was the irregularity of the way the men entered Britain that was the greatest matter of concern. This is highlighted in Home Office correspondence (HO45/13392), with men using the continent to board ships bound for the British coast as a way of going under the radar of surveillance.

In Home Office correspondence, the inability to identify men using passports issued in foreign consuls and then entering Britain at one port, before attending another port for work, quickens the call for a need for more formal identification (HO45/12314). For boarding housekeepers, the need to ensure a steady flow of men into the country was paramount and they were often at the forefront of defending men’s claims to be British.

For men coming during the interwar period from what is, today, Yemen it would have been very confusing on one level when confronted with categories such as ‘British Protected Person’ or ‘British Subject’. They may well have assumed that borders and identities were porous and found the fact that someone registered as coming from Aden was acceptable and someone else registered as coming from the surrounding areas was unacceptable, somewhat baffling. Men stated that unemployment was a problem back home, and the opportunities to find work in Britain and to earn higher wages was a pull. In that way, Goar was following a line of men who saw limited prospects in their home territories and continued to seek opportunities abroad, despite the challenges this posed.

There are many aspects of Goar’s story where there are missing details. How did he maintain himself over the period 1931-33, when records tell us he was unemployed having been discharged at ‘Tyne Ports’? We know from the stories of other men that their fellow countrymen supported them in times of need and there were also cases of boarding housekeepers helping. Further questions remain. When did Goar arrive in Cardiff? What caused Goar to be admitted to hospital on 20 March 1933 in Cardiff, and why was he not discharged until 12 April? Finally, what happened to Goar after 1933: did he manage to stay on in Britain or did he return home? Is there anything in local records that could help answer one or more of these questions?

20sStreets is an exploration of local history stories in the 1921 Census, connecting people of the 2020s with people of the 1920s. Find out more.

Ali Abdul and his file informed the play by Hassan Abdulrazzak, ‘The Fireman’, which is now available here: Once British, Always British: The Fireman.

Really interesting! I am so pleased that this blog exists and that you cover such interesting and relevant subjects (and so well).

Thanks to this blog item I really “get” the confusion of Arab seafarers who didn’t know what status they were.

This story reminds me of some of the sparse material in the National Union of Seamen archives at the Modern Record Centre; ‘non-domiciled seamen’ are a headcahe to the union.