Whilst doing research for the ‘Caribbean through a lens‘ user participation project, a chance phone call from a community group in Birmingham led to the uncovering of a remarkable hidden history of Irish servants or indentured labour being employed on English owned plantations in the Caribbean. At The National Archives, we have unique documentation that demonstrates the sale of indentured labour before, during and after the English Civil War of the 17th century. [ref]See HCA 30/636, CO 1/21 and CO 1/42.[/ref] Many thousands of dispossessed Catholic Irish men, women and children were transported either willingly or unwillingly in this period to work on new sugar and tobacco plantations in Barbados, Jamaica and the smaller Caribbean islands including St Kitts, Nevis, Antigua and Montserrat.

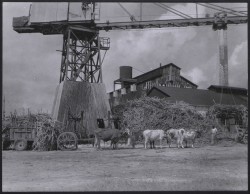

‘Unloading cane at the Searle Estate’, Barbados. (catalogue reference INF 10/44/6)

There has been a deal of controversy amongst writers on this subject in the descriptions of Irish indentured labour as ‘slaves’ or ‘servants’. Certainly it can be argued that willing indenture agreements were signed by individuals and a shipper in which the individual agreed to sell his services for a period of time in exchange for passage, housing, food, clothing, and usually a piece of land at the end of the term of service. However, during the post Civil War period many can be described as ‘political prisoners’ after their land was confiscated by the Cromwellian regime, driven from their land to waiting ships and transported to English colonies. The scarcity of detailed information on the servant trade makes it impossible to ascertain accurately what proportion of labour was involuntary, but the evidence strongly suggests that there was a lively traffic in deportees, especially in the period 1650-1659. In 1658, for example, Thomas Povey, an English merchant with extensive West Indian investments, stated that the majority of Irish servants in Barbados and St Kitts had been transported by the English state for treason.[ref]Thomas Povey’s Diary, British Library, MS 12410, Folio 10.[/ref]

Moreover, John Scott, an English adventurer who travelled in the West Indies during the Commonwealth, saw Irish servants working in field gangs with slaves, ‘without stockings under the scorching sun’. The Irish, he wrote, were “derided by the negroes, and branded with the Epithet of ‘white slaves’”[ref]Catalogue reference: CO 1/21, no. 170.[/ref]

One historian, Thomas Addis Emmet, asserts that most Irish individuals appeared in English records as English. No vessel was allowed to sail from Ireland direct, but by law was obliged first to visit an English port before clearance papers could be obtained. Consequently, every such Irish emigrant crossing in an Irish or English vessel appeared in the official records as English, for the voyage did not begin according to law until the ship cleared from an English port. [ref]Thomas Addis Emmet, Ireland Under English Rule, 1903, page 211.[/ref]

Once in the Caribbean, many plantation owners considered servants and freemen from Ireland as a potentially subversive lot who had to be controlled and kept in a labouring status. The English government allegedly referred to the Irish as: rogues, vagabonds, rebels, neutrals, felons and military prisoners. [ref]Richard S. Dunn, Sugar and Slaves 1624-1713, Jonathan Cape, 1973.[/ref] Punishments for attempted escapes included branding the letters ‘FT’ (Fugitive Traitor) on the servant’s forehead.

General views of industry and agriculture, used in the St Lucia report for 1953-54 (catalogue reference CO 1069/385)

One assembly member in Barbados is quoted in 1667 as stating, ‘We have more than a good many Irish amongst us, therefore I am for the downright Scott, who I am certain will fight without a crucifix about his neck’. [ref]Catalogue reference: CO 1/21, folio 108.[/ref]

By the third quarter of the 17th century on the island of Montserrat, the Irish immigrants were in the ascendancy. A 1678 census shows a vibrant community of almost 1,900 Irish men, women and children – a verifiable 50% of the population – existing as either indentured servants or freemen. Comparable figures for the other Leeward Islands were 26% Irish on Antigua, 22% on Nevis, and 10% on St Christopher. [ref]Hilary McD Beckles, A ‘riotous and unruly lot’: Irish indentured servants and Freemen in the English West Indies, 1644-1713, William and Mary Quarterly XLVII, 1990.[/ref]

Successive governors promised immigrants religious tolerance and easy access to land ownership, and servants from Ireland as well as Irish freemen from Barbados and the Leeward Islands responded in the period 1660-1700. Jamaica became the leading West Indian destination for Irish and English servants departing from Kinsale, Bristol and London in this period.

The legacy of such a diaspora today is that on several of the Caribbean islands there are place names such as Cork Hill, Kinsale and Roche’s Mountain from the Emerald Isle. In islands such as Montserrat, St Patrick’s Day is a national holiday among the inhabitants and the telephone directory contains page after page of Irish names such as Allens, Ryans, Daleys, Farrells Rileys and Sweeneys.

This is a very interesting article about a relatively unknown subject of British and Irish History. I am glad that you have added further sources to investigate as I would like to learn more

Why not turn some of this history into a movie? A lot of people are unaware that the Irish were in fact slaves and not free men

Thank you for this article as I am a product of Irish ancestry out of Montserrat and I had very little information concerning this.

Hope this link is still active. My grandmother was a Yearwood from Montserrat. Since the island was so small, there is an excellent chance we are related. Please send me a reply.

This is quite a timely piece of what was know but not explained or glossed over. There have been stories told to me by my father about the Irish in Montserrat; and, the names of person and places are quite alive and well till even now. what is new is the chronology of the dastard deed committed for greed and avarice, and the nature of man’s in-humanity to man. “all that is seemingly old is new without intrigue”.

W.G

My Great Grand Father Was an O’Reilly I always Wondered How they got to Barbados. This seems to be the most likely cause

Please note that comments have been removed from this blog that did not comply with our moderation policy, detailed here: http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/moderation-policy/. Please take care not to post anything that may cause offence to others.

I am Caribbean from African heritage. I recently had a DNA test done at Ancestry.com and found out i was 6% Irish (in addition to other countries). I started to dig in a little and was totally shocked there were Irish slaves sent to the caribbean. As an Afro-Caribbean, this is very interesting info to learn. It has opened my eyes to view the mutli-culteral and inter-racial mixer of the Caribbean people in a new light.

Where can one research the English passenger lists of Irish transported? I have an Irish/West Indies connection however the surname of the ancestor is Baptist but she ended up back in England (Cockermouth) in the 1800s.

Any suggestions where I can start looking??

On Ancestry.com uk I found at least 20 certificates of Afro Caribbean women and children with my Irish surname in it’s original spelling, not the present day one. The so called “owners” of these women and children did not have this surname? is there any way I can find out why these people were given this name? Also how can I trace what happened to them and if any of them may hopefully be my Afro/Caribbean ancestors?

Hi Linda,

Unfortunately we’re unable to help with family history requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

I hope that helps.

Nell

It is a testament to the Irish spirit and culture that our language and our ways endured, despite the greedy English at that time. Cromwell dressed his motives up as anti-papism when in actual fact he was motivated by greed – he received money from the ‘Adventurers’ who were to come into the lands left behind by the dispossessed and enslaved Irish. He also received five shillings for each man, woman and child sold. The definition of genocide is 10% of a populace – Cromwell reduced it by half. This represents an enormous scything of the gene pool and of the cultural richness and inheritance of the Irish. I can’t believe there are people online trying to claim descendancy from Oliver Cromwell – I’d sooner be related to Hitler than that wart-faced degenerate.

I have just returned from Antigua and met two people with my surname “Mannix” who were Afro-Caribbean and born in Antigua. I was born in Liverpool a port that was a main player in the triangular trade and movement of African slaves. It is ironic that I have never heard the story of the Irish slaves and the fact that they all had to leave from an English port by law would suggest that many probably left through Liverpool. A part of history erased from the cornices of my city and our education system. Disgraceful

http://www.snopes.com/irish-slaves-early-america/

I have also read To Hell or Barbados. It is a shocking read and not known of much by Irish people in my experience. I think that a lot of the ‘willing’, indentures were for 10 years and many of them died of ill use and disease within that time.

I wonder if the ‘willing’ takers of indentures had any idea of what they were going to. I doubt it very much and what they were leaving under Cromwell etc may have seemed much worse than anything that they could envisage ahead of them.

A Jamaican friend told me of a ‘tribe’ of people of Irish ancestry in the middle of the island. Many of them had red hair and used Irish modes of speech and culture. They were ‘shy’ of outsiders and kept to themselves.

(Posted this reply in error to another comment but was meant to be posted as a general reply to the blog author)

I would hardly describe Thomas Addis Emmet as an ‘historian’. The claim that ‘Irish individuals appeared in English records as English’ does not quite ring true. It is well documented that English convicts were transported to the Caribbean and your quote

‘during the post Civil War period many can be described as ‘political prisoners’ after their land was confiscated by the Cromwellian regime, driven from their land to waiting ships and transported to English colonies…’

also applied to English political prisoners under CromwellLiam Hogan’s extensive research on the ‘Irish Slaves’ myth is worth reading and available on line.

In 1667 , Governor William Willoughby was the one who said …..I am certain will fight without a crucifix about his neck’. based on pg 228 of Caribbean Slavery in the Atlantic World by Verene Shepherd and Hilary McD.Beckles

historians have tried to water down the language used to describe the war crimes undertaken by Cromwell and his allies and the subsequent Irish slave trade. Cromwell undertook a savage murderous campaign in Ireland (Drogheda and Wexford for example). He deported many tens of thousands of men and then put to slavery tens of thousands of Irish men, women and children primarily in Barbados. Yes, indentured servitude existed before then, but that turned out to be indentured slavery. But what happened in the 1650s was a clear slave trade from Ireland to Barbados. Why try to deny it?

My daughter married a L’Antigua. He certainly has the appearance of your classic Irishman, and he said his heritage is Irish; but with the name L’Antigua, I couldn’t make sense of it. I had never heard this history, of the Irish being enslaved. Another article I read said the African slaves at least brought respectable prices at the markets whereas the Irish were sold for little or nothing and very badly treated. It’s a horrifying revelation.

For 60 years I have desperately a tempered to trace my. Irish Ancestry but it’s not only ancient civilisations in South America and North America was totally destroyed but so was the Caribbean all due to the wonders of religion slavery was not just black Africans Irish and Scottish as well as English from Cornwall and Devon

I propose we should commemorate the suffering of Irish innocents, especially women and children, under English (and later, British) control over the centuries, since the Anglo-Norman invasion of 1169. An Irish ‘Remembrance Day’.

PLEASE NOTE: Due to the age of this blog, no new comments will be published on it. To ask questions relating to family history or historical research, please use our live chat or online form. We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.