The National Archives digitises over 40,000 records every year, dramatically increasing the accessibility of the collection by bringing documents to your home.

But how do staff at The National Archives enable this type of access?

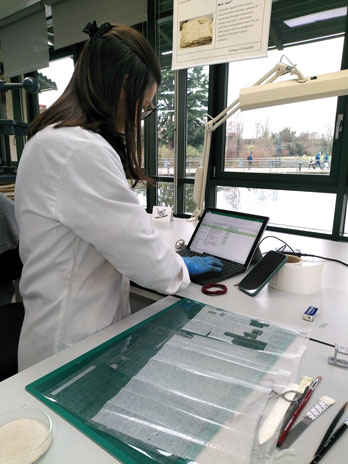

We work with a variety of publishing partners who choose records of national, academic, and personal importance for digitisation. Records selected for digitisation come in a variety of different formats and conditions, and so prior to imaging they are surveyed by a team of conservators. This enables the teams to understand the conservation and handling needs of the records.

If any conservation treatment is required, it is conducted by the same team. The records are then imaged by a team of photographers, trained to capture historical material. Prior to publishing, the images are processed to ensure they are the best quality possible and include important descriptive and administrative information embedded in each photograph (called metadata).

The National Archives employs a team of conservators in the Collection Care Department who specialise in treatment and creating handling guidance that specifically enables the image capture of objects, and fit-for-purpose interventions aimed at preserving objects throughout the digitisation process.

I spoke to members of this team to better understand their roles, their career paths and the skills needed to work as a conservator specialising in digitisation.

How did you get into conservation for digitisation?

Rebekah: You need particularly good time management, the ability to record accurately and problem solve. It’s important to find a way to capture information accurately in a quick way, you must be very pragmatic. It’s the same when it comes to the practical conservation treatments, you must be very pragmatic and focused on how long things take.

Marta: Yeah, record keeping is one of the things that is most different to what you’re trained for because we are trained to be specific and detailed. You create records of everything and pictures of every stain and every tiny tear. For this job you can’t do all these things so it’s a mental shift of what’s necessary as well.

What skills have you learnt on the job?

Flo: Building on the time constraints, what I’ve learned is that I can make decisions and trust my own judgement and be judicious with my treatments and I can ask for help when I need to. You build that confidence in yourself to be able to think ‘I’ve seen this before or I know what to do here.’

Communication skills as well. We work closely with the scanning team and the scanning operators because we’re all part of the digitisation process. So being able to communicate with them, share knowledge, and receive knowledge from them is an important skill that you develop in this role.

Camilla: One of the skills you learn very quickly is trusting your own judgement and honing your skills. You either know or you don’t, and if you don’t you can identify the skills that exist around you and who can give you that information. There’s an element of building a catalogue of things that you can turn to very quickly, and that can either adapt from your past experiences or knowledge you learn on your course.

It’s also important to understand the constraints of imaging. Sometimes when you have a large object you need to know how you can help to handle it, and how it can be photographed in a way that’s not going to put the object at risk.

Rebekah: I had an introduction to condition-surveying collections in my course, but it was never really put into practice in any significant way before this job. This role has been incredibly useful for developing this skill, albeit in quite a specific way as you’re surveying for digitisation.

Like Flo mentioned, we work closely with the scanning team and part of our role is to give handling training so being able to talk about conservation, damage and handling in an accessible way is something I’ve developed more in this role.

What is your one piece of advice for those interested in a career in conservation for digitisation?

Rebekah: It’s quite useful to volunteer on some digitization projects if you can. I did that before I started this job, not necessarily because I had a focus on conservation for digitisation, but because I wanted to get hands-on experience working with heritage and heritage projects. It can be valuable in teaching you the constraints of treatments and objects and you can learn about how imaging equipment is used.

I hope you have enjoyed reading about this specialist role within The National Archives. Conservation for digitisation is a unique form of conservation. The work requires excellent project planning skills, attention to detail and extensive knowledge of the wide varieties of archive materials.

I would like to thank Camilla, Flo, Jennifer, Marta, and Rebekah for taking the time to speak to me about their work. If you are interested in finding out more about digitisation for conservation, a number of our blogs explore some of the team’s past projects:

- Digitising little treasures – Part 1: Egbert Rizzo and the making of an SOE Agent

- Digitising little treasures – Part 2: The Edouard Line

- Beyond 2022: Conservation for digitisation

- The removal and/or care of pressure-sensitive tape from paper

- Letters of Note: Preparing the Prize Papers for digitisation

- Digitising and conserving black cultural history

- Preparing a highly fragmented book for digitisation

- The conservation of MH 47: Preparing military tribunal records for digitisation