Following a 1,500km bicycle journey and two weeks at sea, Egbert was finally back in the UK, and just a few months later, he was ready to embark on a new mission as a Special Operations Executive agent.

On the 4 April 1941, Egbert boarded HMS Fidelity[ref]HMS Fidelity was a ship that operated off the coast in Southern France under the SOE (Special Operations Executive). During 1941 and 1942, it landed agents and picked up escaped prisoners, disguised as Spanish or Portuguese freighters.[/ref] in Liverpool and headed to Southern France. He had a fake French national identity card, 42,000 francs and a lot of courage; he hadn’t been provided with any contacts or directions, he was on his own.

HMS Fidelity reached the French coastal commune of Le Baracarés on the night of 23 April. Despite struggling with high winds and a flooded river, Egbert landed safely – albeit drenched, mourning the loss of his suitcase and ‘a most useful raincoat’. He was provided with a bicycle, which once again turned into his most trusted companion, and at the break of dawn he was off to Perpignan.

Egbert set up post in the home of the Carrères in Perpignan, a friendly couple he had met previously and who had agreed to provide a room for him. This was a strategic location: situated in the Vichy zone, Perpignan was not under German directive, and its proximity to Spain and the Mediterranean Sea was promising.

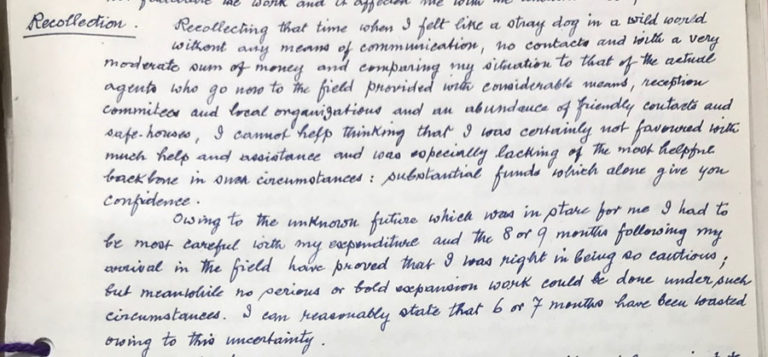

In his report, Egbert describes the first few weeks and months of his mission in great detail. His original food card remained in Paris and he was not provided with one before leaving the UK, and due to food scarcity, he couldn’t ask the Carrères to feed him nor find any food in town.

‘I therefore lived for a fortnight on almonds, figs, nuts and pastry, but no bread.’

For eight months, from his arrival in April 1941 to January 1942, Egbert occupied a ground floor cellar with a camp bed. He lived without any heat and had little to no contact from headquarters, receiving no further funds, which he had been promised. He struggled to find food and allies, as most people expected to be paid for any clandestine work they carried out. His wife Anna did visit him after they made contact, which he describes as an immense pleasure. But despite all these setbacks, Egbert’s ingenuity and courage drove him to create one of the most successful communication and evasion organisations in the history of the SOE.

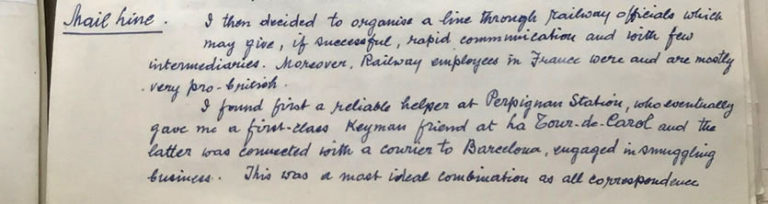

While awaiting funds and instructions from HQ, Egbert decided to set up a mail line through railway officials, stating ‘most of the railway employees in France were and are very Pro-British’. He found a man at Perpignan station who connected him to a first class keyman at La Tour de Carol. It took some time to finalise the mail line because he had no contacts in Barcelona, but by early September 1941, the line was established and working successfully. Hundreds of messages and reports were transmitted from Perpignan to Barcelona, passing through Puigcerdá in the Pyrenees.

This mail line was extremely important in the transmission of messages from and to HQ, and maintained a network of agents informed and involved in the resistance effort. There was never a casualty involved in its operation, something that Egbert was very proud of.

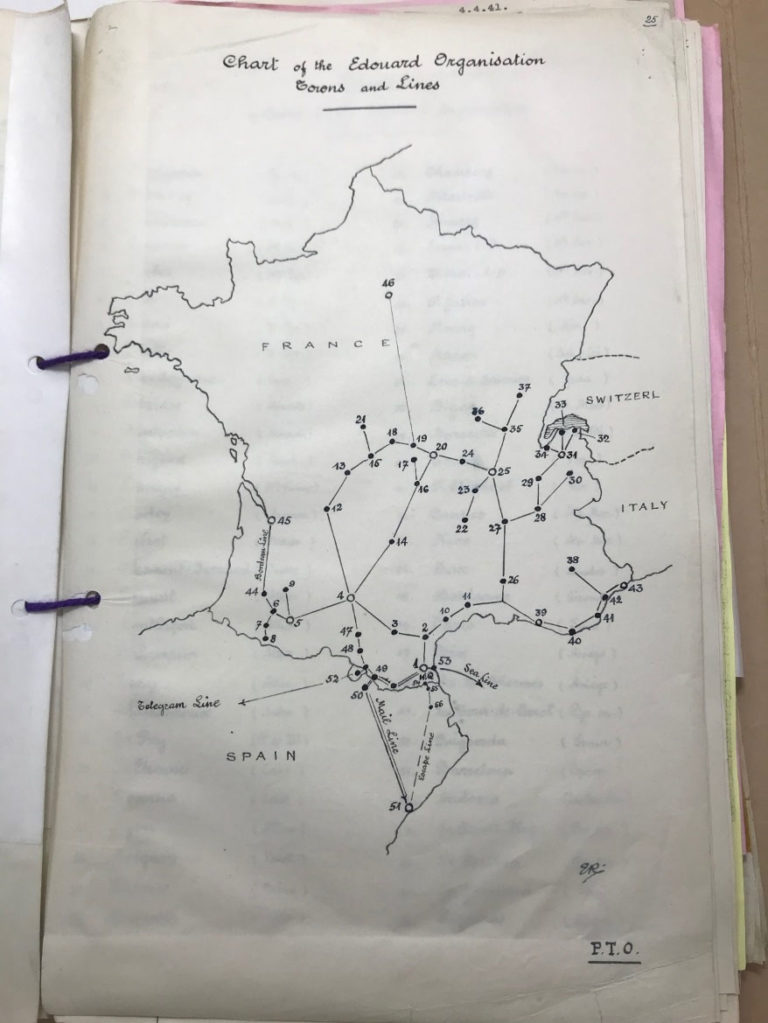

In September 1941 Egbert received orders from HQ regarding his first operation: to arrange for safe passage and safe housing of five agents. In October, another dozen agents arrived; they were all sent to different towns and safe houses, extending the network of the Edouard organisation.

By the summer of 1942, the Edouard line had developed into an important net of agents, safe houses and post boxes that were tended to by couriers in dozens of different towns, including Perpignan, Toulouse, Bordeaux, and Barcelona. Egbert also safely prepared the crossing of several people into Spain through the Pyrenees, although further development of this escape line was impeded by a continuous lack of funds.

Things took a turn at the start of November, when Egbert was alerted to the occupation of the Vichy Zone by the German troops. Perpignan became a dangerous place, swarming with German soldiers, W/T operators and the Gestapo. Reluctantly, Egbert decided to leave for Spain in the hopes of continuing to lead the operation from Barcelona.

On 19 November 1942, Egbert left Perpignan never to return again. His plan to direct the Edouard organisation from Barcelona never flourished. His journey to cross into Spain was long, hindered by the difficulty to find a safe house in Barcelona. On the night of 2 December, Egbert was headed for La Estrada, where a safe house awaited, but the darkness of the night and the roughness of the mountain caused Egbert to trip and fall into a crevasse.

‘My foot was broken and hanging and my leg bone was sticking out of a nasty wound at the ankle.’

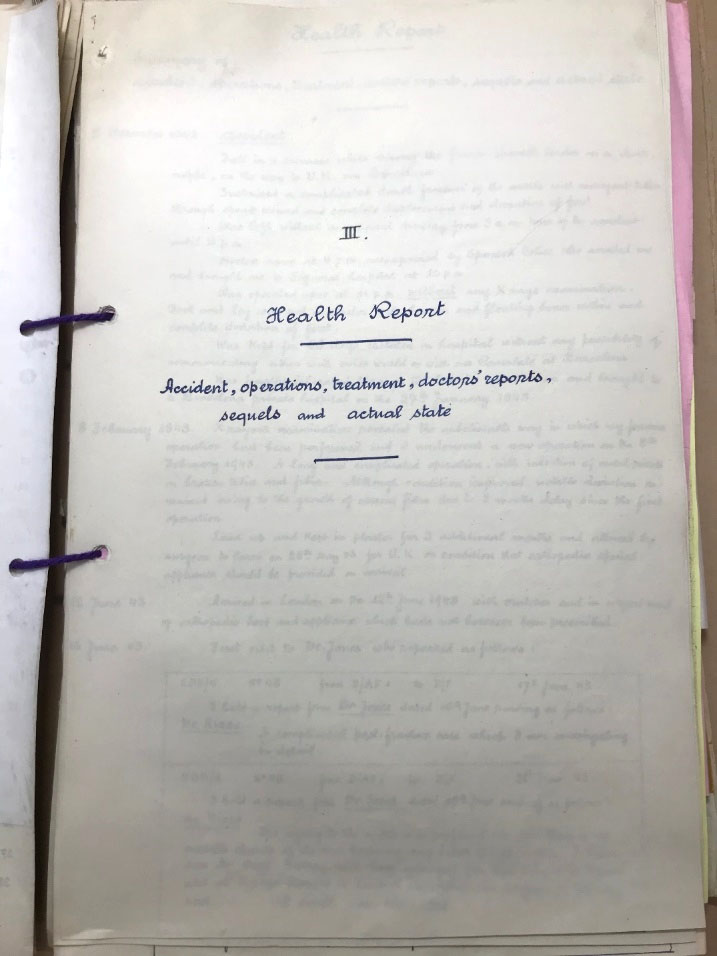

Egbert spent two months in the Hospital de la Santa Cruz in Figueras, Spain, bedridden and unable to contact anyone to alert them of his whereabouts. On 24 January 1943, he received a message from an agent, hidden in a box of sweets. Three days later he was picked up by another agent and driven to Barcelona. He spent another three months in a private hospital in Barcelona, during which he underwent a second leg operation. Crippled and disillusioned, Egbert returned to the UK by way of Madrid, Gibraltar and Lisbon, arriving in London on 12 June 1943.

He was appointed as staff for the DF section of the SOE (responsible for establishing escape routes); his hopes of returning to the field were shattered by his officials. Egbert signed the report, which includes detailed information on the agents and networks of the organisation, as well as an expenses summary, health report and Curriculum Vitae, on 30 September 1943.

And so, Egbert’s story ends. We don’t know how he lived the rest of his life, if he ever saw his wife again, or if he was able to walk without crutches. A Google search brings up a few Second World War espionage books that mention Egbert V H Rizzo and the Edouard organisation, but none mention the full story of his intrepid life. Some further research reveals that Anna Rizzo, Egbert’s wife, was arrested by the Germans in 1944 and executed at Ravensbruck concentration camp on 25 April 1945. She too was fighting for the resistance.

This is a document of incredible value, in which a man has, detail by detail and word by word, described his own journey of escape, evasion, survival and resistance. By writing this document Egbert provided us with a story that would otherwise have gone unknown, but why did he do it? Why did he meticulously handwrite tens of pages? Joseph Quinn, specialist Second World War researcher at The National Archives, argues that due to the high level of detail, particularly regarding funding and expenses, this might have been a military pension application; Egbert was asking to be reimbursed for his service.

As bureaucratic as a pension application might be, Egbert’s story transcends this report and comes to be what I believe is a ‘little treasure’. And as a conservator, there is nothing more rewarding and special than treating, preserving and taking care of such little treasures.

Special thanks to Joseph Quinn, for chatting to me about the Second World War, the SOE and providing so much insight and clarification.

The story of HMS Fidelity reads like an adventurous spy story in itself and occupies many files at the National Archives.

A French armed merchant cruiser the ship escaped France and was offered to the Royal Navy by its captain, who besides wanting his crew – including a Madeleine Bayard (later Madeleine Barclay – see below) who could be described as his mistress and had links with French intelligence from when she and her husband ran a rubber plantation in French Indochina – to be commissioned into the RN (under false names to protect families and friends remaining in France) tried to claim prize money from his new employers,

Much of the paperwork in the files is concerned with tracing the cargo and exchanges with Admiralty lawyers. Other files concern discipline issues and suicide amongst the crew and dealing with the captain who thought his new rank should be higher than it was.

The circumstances of loss of the vessel on 1 January 1943 are another adventure, with (as I recall) only a handful of crew surviving. Given the activities that the ship was involved with its story has only came to light long after its loss.

It has been said Madeleine Barclay was the only member of the Women’s Royal Naval Service to be lost at sea in operations during the Second World War. She and her shipmates are commemorated on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial on Southsea Common.

Madeleine is honoured in the Allied Special Forces Memorial Grove at the National Memorial Arboretum, Alrerwas. UK. http://www.warmemorialsonline.org.uk/memorial/279209.

For the story of HMS Fidelity and the operators see Claude and Madeleine a true story of love, war and espoinage”by Edward Marriott pb by Picador

Peter Dowding

E. Rizzo was the husband of the sister (Anna) of my maternal grand-mother.

Anna was arrested by the Gestapo in Perpignan in January 1944, deported to Ravensbruck in April 1944, where she was murdered on 28 March 1945.

Egbert spent the last part of his life in Nice where he died in 1958. He his buried in the family tombstone in Garches (next to Paris) cemetery.