This blog is part of a series supporting the release of the latest episode of On The Record, a podcast by The National Archives, about Colonial Office Records. You can listen to the podcast here.

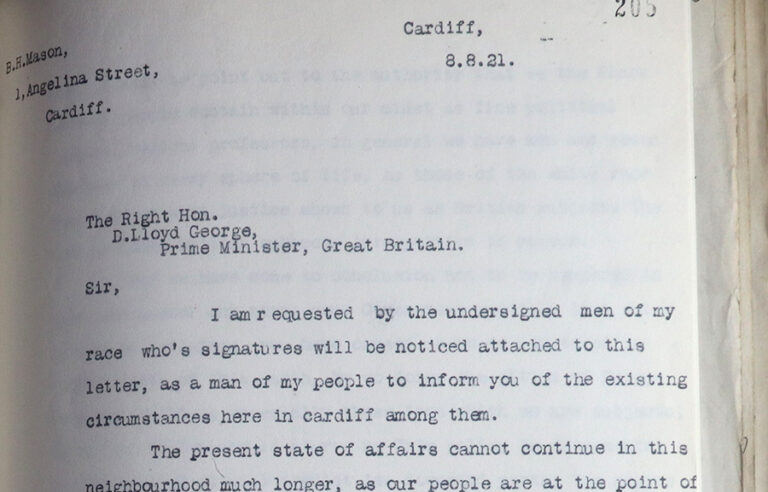

A letter in our collection

Some years ago a letter in our collection from a group of black working-class men caught my attention. It tells a story about a very active interwar global movement for black self-determination, at a time when there were many competing visions of what the future could look like.

Bernard Mason, the author of the letter, is writing on behalf of himself and a group of black seamen to the then Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, in August 1921, a couple of years after the 1919 rioting.

The letter opens with a straightforward address to the Prime Minister:

‘I am requested by the undersigned men of my race who’s signature will be noticed attached to this letter, as a man of my people To inform you of the existing circumstances here in Cardiff among men.’

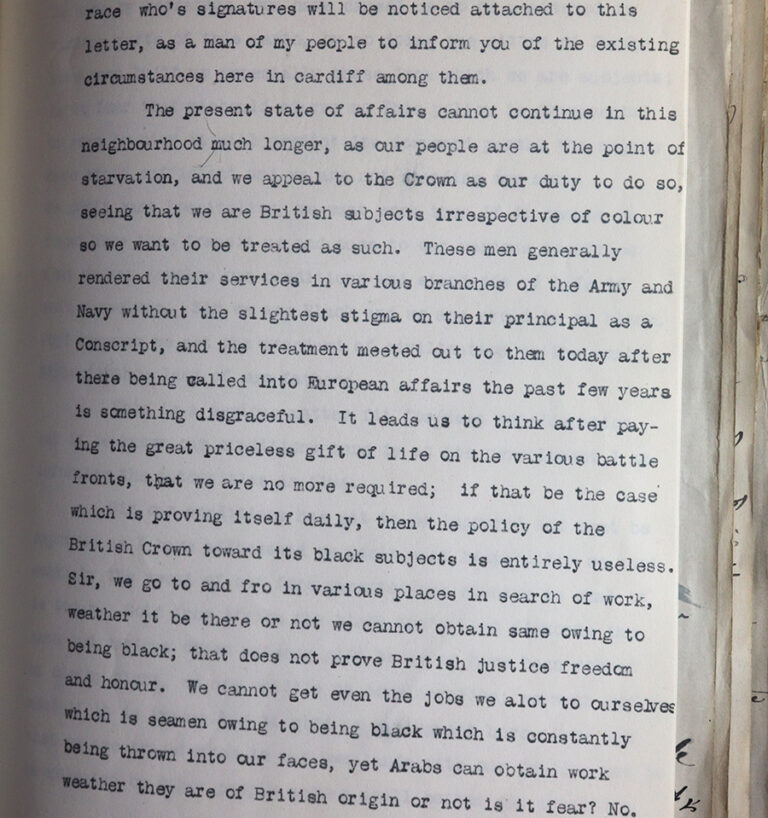

The opening sets the tone for the rest of the letter which is an uncompromising call for equality and taking pride in being black. It emphasises how bad the situation has become for black seamen in ports like Cardiff and demands that all British subjects should be treated the same. It is at pains to convey, as other letters and correspondence from colonial subjects around this time also do, the sense of betrayal that, having served the empire, they are being treated in this way:

‘It leads us to think that after paying the great priceless gift of life on the various battlefronts, that we are no more required; If that be the case which is proving itself daily, then the policy of the British crown toward its black subjects is entirely useless. Sir, we go to and fro in various places in search of work, weather (sic) it be there or not we cannot obtain same owing to being black; and that does not prove British justice freedom and honour.’

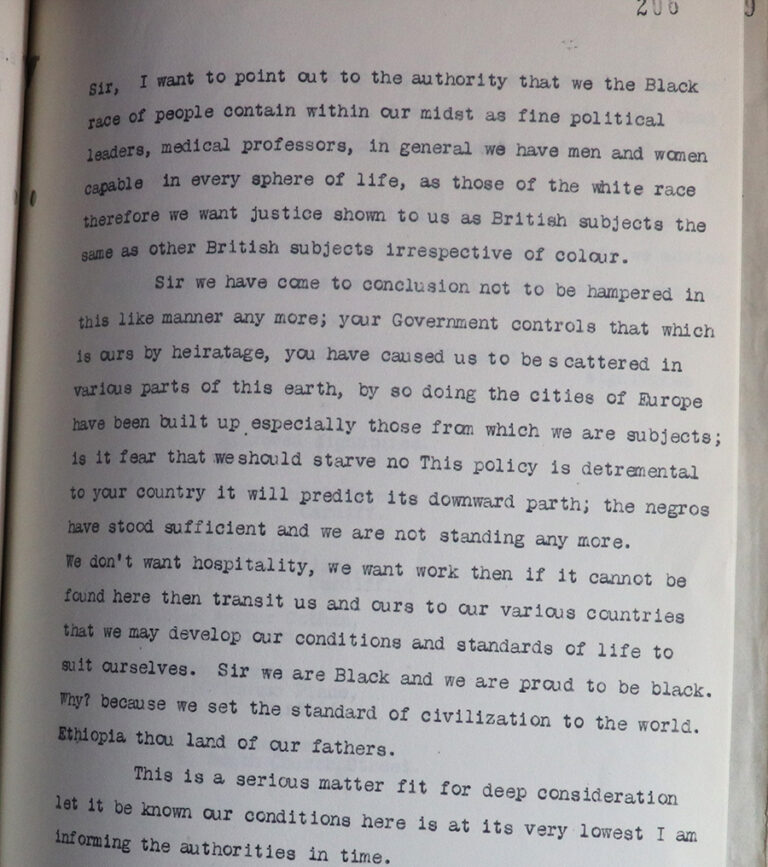

But it is the next passages that really alert you to how much influence Garvey and his movement for black pride are having:

‘Sir, I want to point out to the authority that we the black race of people contained within our midst as fine political leaders, medical professors, in general we have men and women capable in every sphere of life, as those of the white race therefore we want justice shown to us as British subjects the same as other British subjects irrespective of colour.’

We certainly know from other files in our collection that officials at the Colonial Office, where this letter is filed, such as Gilbert Grindle, were writing notes about the fact that whatever the imperial authorities did to assuage the economic or social challenges of the time, they could not overcome the fact that black people were now thinking of themselves as equal to white.

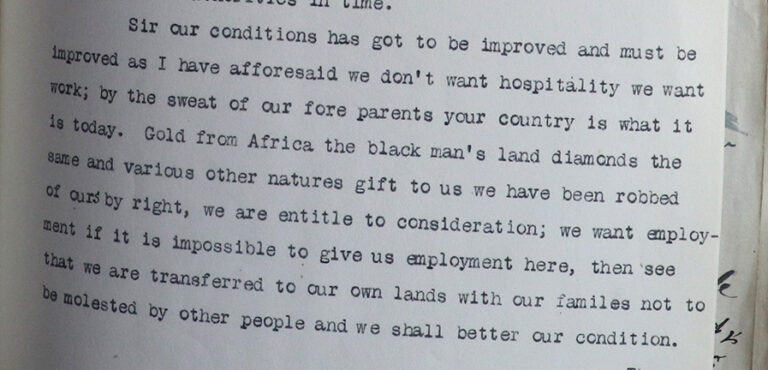

The letter ends on a powerful reminder that it is on the back of the sweat of black people and the injustices they have faced that Britain has been made great:

‘Sir our conditions has got to be improved and must be improved as I have afforesaid (sic) we don’t want hospitality we want work; by the sweat of our fore parents your country is what it is today. Gold from Africa the black man’s land diamonds the same and various other natures gift to us we have been robbed of ours by right, we are entitle to consideration.’

And in an extraordinary last few sentences the author states that if Britain is unable to find employment for its black subjects, it should do the right thing and make provision for her subjects to be returned to Africa:

‘we want employment if it is impossible to give us employment here, then see that we are transferred to our own lands with our families not to be molested by other people and we shall better our condition.’

Garveyite message

At the heart of the letter the demand is clear: they wanted employment. But the demand is couched in a way that is unique. While referring to themselves as British subjects and members of the Empire, the men are also aligning themselves with new and radical ideas. And for this group of men, who are not elite, they have been influenced in Cardiff by spokespeople who are spreading the nascent Garveyite message.

Scholars such as Tony Martin, Adam Ewing and Jack Thorold have pointed out that the power of the Garveyite message was its appeal to working-class, black people and that this message travelled far and wide, a message on how they could self-organise and demand change on their own terms.

I have studied letters from the time that similarly address issues of unemployment, and we have in the past used these in our projects and previous podcasts (Love divided and A Stranger in a Strange Place). But I have not read anything quite like this letter signed by a group of black, working-class men. And from exploring the 1921 Census, it is possible to find out a little more about most of them.

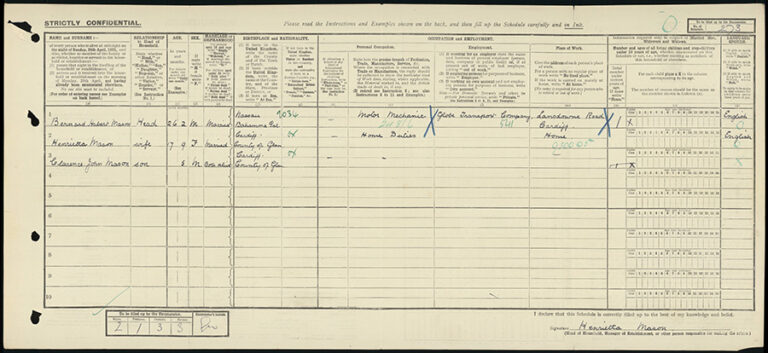

Bernard Mason is the writer of the letter; he is the youngest of the group, aged 27, and appears to be the most qualified. He works as a motor mechanic and is from Nassau in the Bahamas.

The other signatories are all seamen variously aged 28, 31, and 37. The majority are married to women from Cardiff or Liverpool and say they are from St Vincent (British West Indies), Demerara (British Guiana) and Barbados. At the time the census was taken, at least three of the five signatories were unemployed.

We know from scholars’ research that the Garveyite message was being spread in different locales through meetings and the distribution of print, notably, the Negro World paper. The paper is an important source for the information we have about this kind of organising activity. It was also a message that was appealing to people across an African diaspora taking in the Caribbean, the US and Britain.

In a post-war world where colonised people were renewing their demands for racial equality and asserting pride in themselves, the Garveyites were a notable voice. In August 1920, Garvey’s movement hosted its first international convention and those attending adopted a declaration of the rights of black people. They also adopted an Ethiopian national anthem. The reference to Ethiopia and a return to Africa in the letter is therefore unsurprising.

Garvey and his movement

Marcus Garvey, born in 1887, came from a humble background to become a notable public speaker and trade unionist. Before the First World War he toured Europe, spoke at Hyde Park Corner, attended law classes at Birkbeck College and got involved in a Pan-African newspaper, The African Times and Orient Review.

However, Garvey really came to prominence at the end of the First World War as a spokesman and figurehead for a global movement fighting for black rights and equality. He founded the United Negro Improvement Association. The Association had various strands including a newspaper, the Negro World. His mixture of radicalism and black nationalism made imperial authorities very uncomfortable.

When the now infamous Coloured Alien Seamen’s Order was issued, it was his paper, the Negro World, that was one of the first to protest. We have a cutting in our collection of the paper, where the case is made for fair and equal treatment of black seafarers. In one noteworthy example, the paper provides a personal example to make its case:

‘Several months ago we examined the “alien” passport of a seaman born in Sierra Leone, but domiciled in England for many years, and we were surprised, then amused to note that under the heading “nationality” a pen stroke was placed by the clerk who filled out the particulars on the passport. So according to John Bull’s new strategy, his black subjects in England have no nationality. It is to laugh and ask what next?’

(HO 45/12314)

This was a typical issue that Garveyites would take up: the rights of working people. It was on the back of the protests led by Garveyites through, for example, the Negro World newspaper that led the Colonial Office and heads of colonies to single them out.

In correspondence in our collection you have references to Garveyite sedition. Britain along with France banned the Negro World newspaper, imprisoned Garveyites and restricted the movements of Garvey from places such as Bermuda and the Bahamas.

It was the Negro World paper that was part of Garvey’s movement that led on the challenge to the Order. Its arguments reflected how over time a radical politics of equality and justice inspired by Garvey and Garveyism was feeding into the protests and calls to challenge authority.

The impact of Garveyism

Some measure of the impact of Garvey’s politics, in a period where Garvey’s own political fortunes had turned for the worse and he was made to stand trial on charges of fraud (and was imprisoned in 1925 for three years), was the response from colonial governors to protests led by Garveyites to the treatment of black sailors.

A letter from the Governor of Antigua in July 1926, in reply to a letter from the Colonial Office saying that the matter of regulating coloured seamen is necessary despite the protest of the Garveyites, illustrates the point:

‘and the attempt that has been made to do so has caused the indignation of the Marcus Garveyites’ seven eighth of whom the Governor claims are not British subjects. The Governor is saying that one of the key reasons for issuing the cards was also to address the fear about sedition and he explicitly states as a way of controlling the Garveyites.

(CO 318/386/2)

Further reading

- Marcus Garvey in the ‘Dictionary of National Biography’, Tony Martin

- ‘The Age of Garvey’, Adam Ewing

- ‘Black Political Worlds in Port Cities: Garveyism in 1920s Britain’, Jack Thorold

On the Record: Colonial Office Records

In this episode of our podcast, we take a closer look at Britain’s Colonial Office records. This was the government department responsible for Britain’s colonies at various points throughout the 18th to 20th centuries.

We explore three stories found in these records, which provide an insight into the experiences of people living under British Rule.

A most interesting letter, well thought out and written, indicative of the times which unfortunately seem to have not changed.

This is a real eye-opener- well done the researchers – even more so, well done – heroically! – black men and women who spoke up and acted – at cost – in the still-continuing task of alerting us whites that we are all human beings, whatever the colour of our skin! Thank God for these pioneers in that struggle.

Thursday September 22nd:

Referring to ‘John Bull’s new strategy of his black subjects in England of 1919 having no nationality’.

This strategy has not moved on, it is still alive and in use so why ask what’s next?