The nineteenth century was a time of incredible innovation in Britain. Industrialisation, economic prosperity and societal changes were opening up opportunities for new scientific discoveries, industries and technologies. As people read about these developments in the newspapers, they could be inspired to come up with their own ideas to solve problems, improve lives and make money.

In order to protect a new invention from being copied, people had to apply for a patent, which was a complex and expensive process. However, in 1843 the Utility Designs Act was passed into law, allowing inventors to use the Registered Designs system to protect their ideas. This was simpler and cheaper, and so encouraged a wider range of people to get involved in inventing.

The records of designs registered under the Utility Designs Act, held at The National Archives, give an amazing insight into the problems encountered by Victorian inventors and the many intriguing ways they tried to solve them.

Registered Design records are the inspiration for our exhibition, Spirit of Invention, which is open at The National Archives until Sunday 29 October 2023. Find out more about the exhibition and related events on the Spirit of Invention portal.

This blog highlights five people who sent in their designs to protect them under the Utility Designs Act, and discusses the unusual inventions they came up with and the little-known stories behind them.

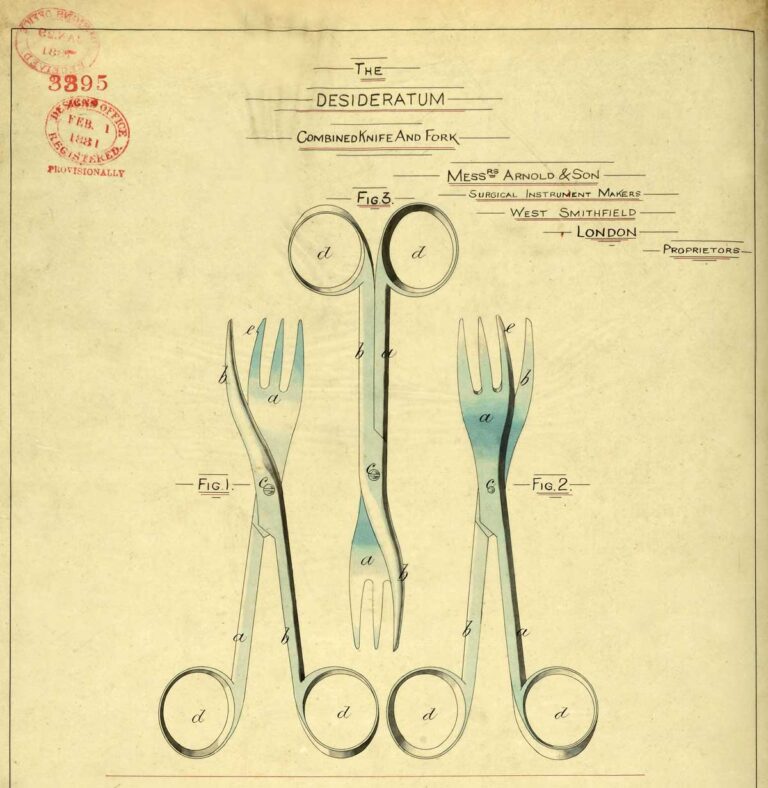

Messrs Arnold & Son: Combined Knife and Fork

In 1829, James Arnold set up business as a surgical instrument maker, based in the City of London. His company operated under several names, known as James Arnold & Son from 1857. 1 They manufactured a range of instruments and appliances, and according to the preface of their 1879 catalogue, they specialised in orthopaedics. 2

They were experimental in developing new designs for instruments and equipment, and you can find several of their designs in the registered design collection at The National Archives. One unusual example is the combined knife and fork. This instrument functioned like a pair of scissors with a cutting edge that could be closed to form a fork. This design made it easier for a person to eat a meal with only one hand, catering to those with disabilities.

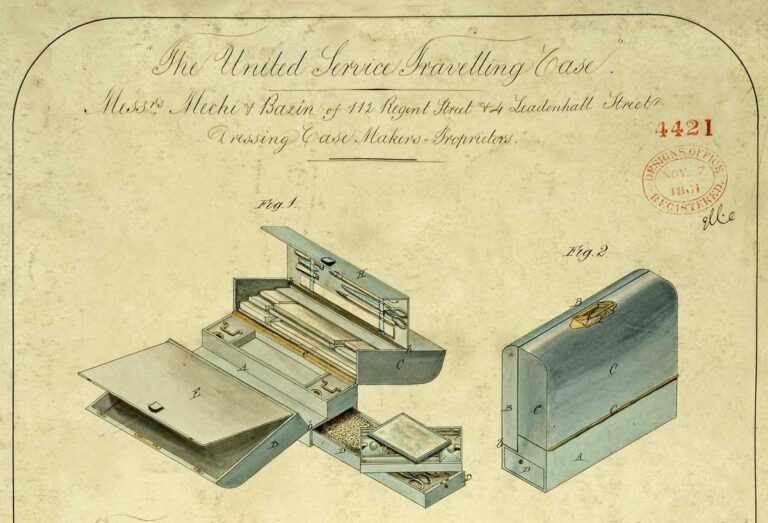

John Mechi and Charles Bazin: The United Service Travelling Case

John Joseph Mechi was born in 1802. His father was James Mechi, an Italian refugee who came to England from Bologna and found work in the household of King George III.

John had a keen interest in innovation from a young age. While working as a clerk, he began to come up with new inventions and in 1827, he set up a business in Leadenhall Street, London, as a cutler and dressing case maker. A few years later he invented the ‘magic razor-strop’, a tool for sharpening razors, which became very popular. 3

John Mechi also took an interest in agriculture, and bought a small farm at Tiptree Heath in Essex where he experimented with improvements to farming methods. He was highly respected for his contributions to agricultural development. He served as a member of the Council of the Society of Arts and as a juror in the Department of Art and Science at the Great Exhibition of 1851. 4

Despite his focus on agriculture, he maintained an interest in a very broad range of areas of design and innovation. His Leadenhall street business continued to thrive and in 1859 he partnered with Charles Bazin to rename the company Mechi & Bazin. 5 In 1861 they registered a design for ‘The United Service Travelling Case.’ This case included multiple compartments, making it possible to use ‘as a writing case and despatch box and as a dressing case or lady’s work box, according to the fittings introduced therein’.

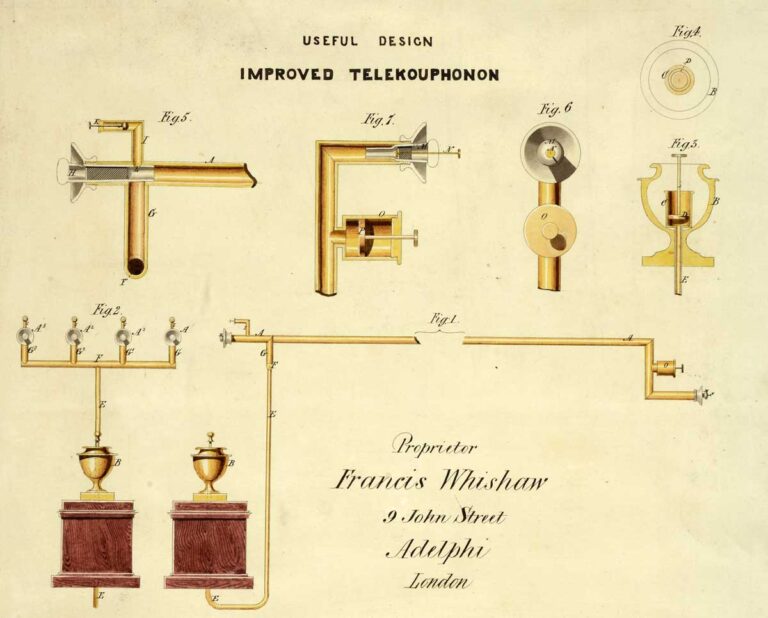

Francis Whishaw: Improved Telekouphonon

Francis Whishaw was a civil engineer who first specialised in railways, but later went on to expand his interests into a variety of projects and materials. He wrote extensively about railways, proposing new lines and methods of operation with the aim to extend the system throughout the country and make it more efficient.

His interest in railways led him to focus on other areas. He invented the hydraulic telegraph and worked on improvements to the electric telegraph, which had been invented at a similar time. He also championed and experimented with a new material in engineering, gutta-percha, a kind of latex produced from the sap of gutta-percha trees, which had been introduced to Britain in 1843. He demonstrated how the material could be used in place of leather for bands for driving machinery, for example. 6

He was perhaps most famous for his contribution to the Society of Arts. As Secretary, he invigorated what was at the time a declining society, and he organised regular exhibitions at the Society. He recognised the importance and impact of exhibitions, and argued that a large national exhibition should be held in the UK. It eventually took place as the Great Exhibition in 1851, a success for which Whishaw could take much credit.

In the same year as the Great Exhibition, Whishaw registered this design for an Improved Telekouphonon, a type of speaking tube which allowed people to communicate over distances in large buildings, mines, trains and ships. The design used gutta-percha to create a long, flexible tube through which people could speak. The invention was manufactured and sold successfully, and today an example can be found in the Powerhouse Collection. 7

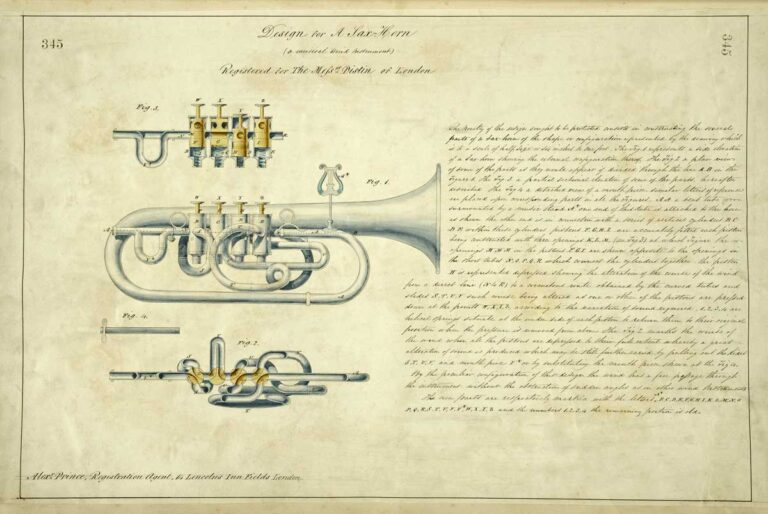

The Distin Family: A Sax-Horn

The Distin Family was a group of musicians who toured Britain and Ireland performing with brass instruments in the nineteenth century. John Distin started his musical career in the military, serving in the Grenadier Guards. He also played in the band of George IV, before forming a brass quintet with his sons, debuting in Edinburgh in 1837. 8

In 1845 John and his son Henry established a business, Distin & Sons, selling musical instruments. They stocked and promoted saxhorns, a new type of brass instrument which had been invented by Belgian musician Adolphe Sax the year before. 9

On 10 January 1845, the Messrs Distin registered their own design for a saxhorn under the Utility Designs Act. The family was very influential in popularising brass musical instruments and contributing to the further development of technologies used in these instruments.

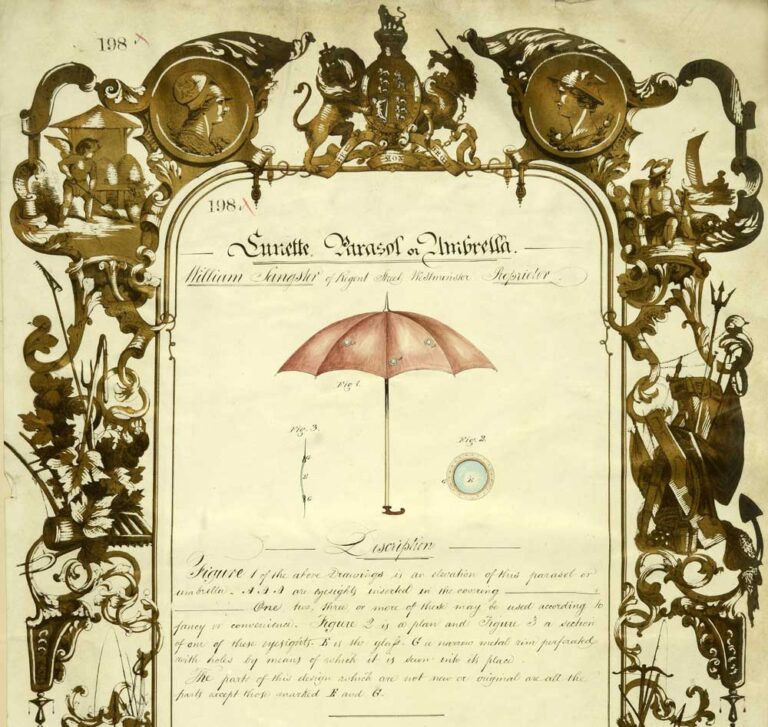

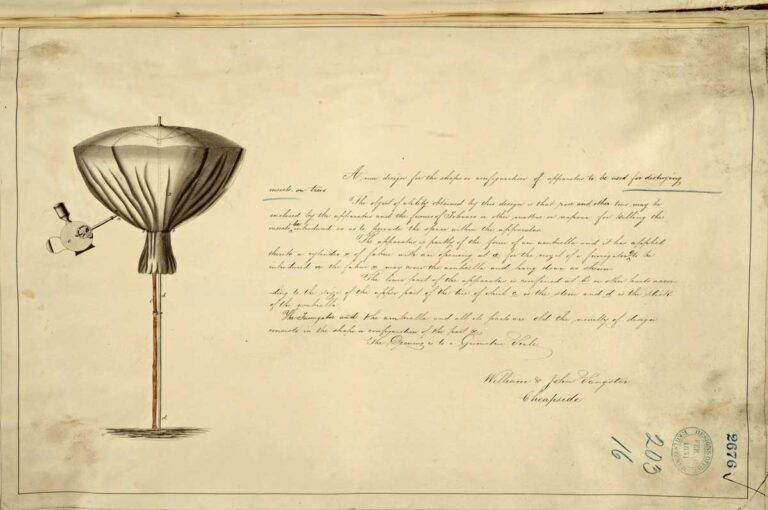

The Sangster Family: The ‘Lunette’ Parasol and Apparatus for Destroying Insects on Trees

In the late eighteenth century, Samuel Sangster opened a business in Fleet Street, London, selling canes and sticks. He was later joined by his two sons, William and John, and the business was expanded to sell umbrellas and parasols. 10

Sangster became well known for its innovative new umbrellas and parasols, and William and John used the registered design system to protect their designs. They took such an interest in the subject that in 1855, William published a book ‘Umbrellas and Their History’. 11

Can it be possibly believed, by the present eminently practical generation, that a busy people like the English, whose diversified occupations so continually expose them to the chances and changes of a proverbially fickle sky, had ever been ignorant of the blessings bestowed on them by that dearest and truest friend in need and in deed, the UMBRELLA?

William Sangster, Umbrellas and Their History, 1855

Two intriguing designs can be found in the Utility Designs collection. On 11 June 1844, William Sangster registered the ‘Lunette’ parasol and umbrella. This design had eye holes, allowing the bearer to peek out through the fabric.

William and John Sangster weren’t just interested in umbrellas, but also anything that could utilise the structure and technology of umbrellas. On 8 February 1851 they registered the ‘Apparatus to be used for destroying insects on trees’. This employed the same kind of frame used in an umbrella to suspend a fabric to cover a young tree, into which insecticide could be pumped. This invention demonstrates very clearly how different unrelated areas of innovation could impact one another.

The Victorian spirit of invention

Inventors in the Victorian era came from a range of different backgrounds and life experiences, but they all exhibited the same passionate drive for innovation. Their interests could be wide and all-encompassing or narrow and focused, but they were very effective at recognising opportunities for improvements they could make to life and society around them.

While people interested in creating and selling their inventions generally needed some financial support to get started, the Utility Designs Act made it a little easier and more accessible for them to protect their inventions. Registered Design legislation has also thankfully left us with an incredible collection of records which can help us to understand the Victorians better.

Some of the inventions discussed here feature in our exhibition Spirit of Invention, which is open at The National Archives in Kew until Sunday 29 October 2023. Beyond these inventions, the wider Registered Designs collection contains thousands of fascinating designs which can be consulted by visiting The National Archives. To find out how to access and research this collection, please see our research guide to Intellectual property: registered designs 1839-1991.

Notes:

- ‘Arnold and Sons 1829 – 1928’, Science Museum, https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/people/cp65081/arnold-and-sons [accessed 31/07/2023] ↩

- Arnold and Sons, A catalogue of surgical instruments manufactured by Arnold and Sons, 1879, Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/yum2g3sn#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&z=-1.1832%2C-0.0921%2C3.3666%2C1.8429tele ↩

- ’Death of Mr. Mechi’, Southend Standard and Essex Weekly Advertiser, Friday 31 December 1880, British Newspaper Archive ↩

- ’Death of Mr. Mechi’, Southend Standard and Essex Weekly Advertiser, Friday 31 December 1880, British Newspaper Archive ↩

- Daniel Lucian, ’Mechi’, Antique Box Guide, 2023, https://www.antiquebox.org/mechi/ [accessed 31/07/2023] ↩

- ’OBITUARY. FRANCIS WHISHAW, 1804-1856′, Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers 1857 16:1857, 143-150, https://doi.org/10.1680/imotp.1857.23802 ↩

- ‘Whishaw’s Telekouphonon Speaking Telegraph’, Powerhouse Collection, https://collection.maas.museum/object/208797 [accessed 31/07/2023] ↩

- Nicholas Temperley, Musicians of Bath and Beyond: Edward Loder (1809-1865) and His Family, 2016, p. 94. ↩

- Ray Farr, The Distin Legacy: The Rise of the Brass Band in 19th-Century Britain, 2014, p. 120 ↩

- ‘W. & J. Sangster, umbrella makers’, London Street Views, 2013, https://londonstreetviews.wordpress.com/2013/01/09/w-j-sangster-umbrella-makers/ [accessed 31/07/2023] ↩

- William Sangster, Umbrellas and Their History, 1855, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/6674/6674-h/6674-h.htm [accessed 31/07/2023] ↩

How about that well-known and taken-for-granted item, the water tap with a replaceable rubber washer? Or more precisely, the high pressure screw-down bib and stop cock. Prior to its patent in 1845, taps had been leaky devices. Its little-known inventor Edward Chrimes of Rotherham died in 1847, but his brother Richard set up business as Guest & Chrimes, brassfounders, which took advantage of public works following the Public Health Act of 1848 to build a company which operated for 150 years. In 1938, 72 inch sluice valves were being supplied to the London Metropolitan Water Board.

See: http://archives.rotherham.gov.uk/CalmView/Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=33-B

and the TNA catalogue.

Have you heard of the Dugdill lamp? Invented by my great grandfather and used widely in the Second World War. I understood that they supplied the Navy. John Dugdill also made electric motors, one of which is on display in a Manchester museum. He was one of the first electrical engineers. His factory was on the A6 in Hazel Grove.

A most informative article which I enjoyed. I live in Canada so can’t attend any of your exhibitions, but do enjoy reading about them. My paternal family came from Scotland (Arbroath & Shetland). Thank you again.

This is brilliant. Thank you.

The Dugdill lamps are fascinating. I am a researcher at Cambridge, trying to learn more about them.