The dominant narrative of post-war ‘race’ relations in Britain begins with the Empire Windrush bringing the earliest Caribbean workforce, and the anti-black riots of 1958 on the streets of Nottingham and Notting Hill signalling the first major instances of ‘race’-related public disorder 1 2. However, there was an earlier phase to this history – one which saw flashpoints between workers of different nationalities housed in Ministry of Labour hostels during the late 1940s. This blog entry will examine this neglected aspect of British history, concentrating on the events at Causeway Green, West Midlands, in 1949, which would lead to racist restrictions on the numbers of black workers allowed to stay at government hostels at any one time.

Post-war Britain faced a massive labour-shortage – estimated at 1,346,000 at the end of 1946 3 – and the government tapped a number of sources for workers, including ex-prisoners of war, Polish ex-servicemen, and eventually the European Voluntary Workers (EVW) scheme.

This scheme sought to recruit displaced persons, between 1947 and the early 1950s, in an effort to alleviate the severe labour shortage in Britain, and aid those made homeless during World War II. The programme was deeply discriminatory and, given the EVWs’ status as aliens, they could be directed to, and kept within, certain understaffed, and frequently undesirable, sectors of employment. This status clearly differentiated them from Caribbean migrants, who, as British citizens, were exempt from such controls.

Thousands of West Indians had come to Britain during the war, either as volunteers in the armed forces or technicians, and while a few remained, the majority returned home. It was the shortage of opportunities, and underdevelopment of the islands under colonial rule, that provided the impetus for many more to seek employment in the ‘mother country’ in the late 1940s 4.

The housing of a number of the new migrants in the vicinity of their employment was organised by the National Service Hostels Corporation (NSHC), which was set up by the Ministry of Labour and National Service in 1941.

NSHC Disturbances

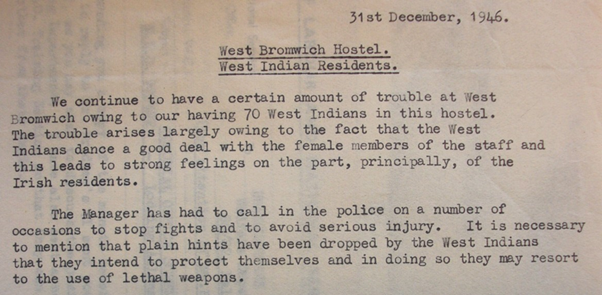

The records of the NSHC report disturbances at their hostels from 1946. The West Bromwich hostel, home to predominantly Irish and Caribbean tenants, witnessed some disorder on 25 December 1946, instigated by the Irishmen’s dislike of black men dancing with white female members of staff at the Christmas party:

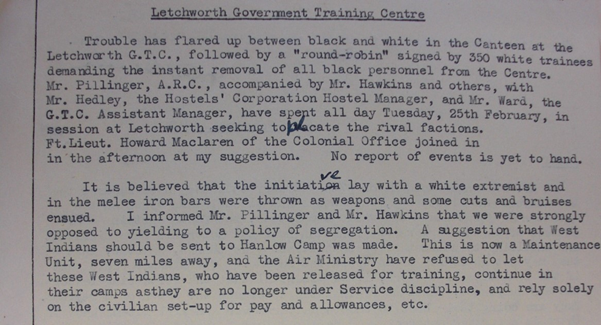

Letchworth Hostel in Hertfordshire saw a disturbance in late February 1947, following, ‘a “round robin” signed by 350 white trainees demanding the instant removal of all black personnel from the Centre.’

The Greenbanks Hostel in Leeds faced trouble on the 25 January 1948, where, in the words of the manager, ‘The cause appears to be racial prejudice – black men associating with white women’ 5. Disturbances had previously been recorded there in September and December 1947. The Sherburn-in-Elmet Hostel, Yorkshire, records a disturbance on the 30 November 1947, as well as a number of other ‘outbreaks of one kind or another’ 6.

Three months later, problems arose at Pontefract Hostel in Yorkshire. In September 1948, Weston-on-Trent Hostel in Derbyshire was the site of disturbances. The hostel at Castle Donnington, Nottingham saw an incident on 1 August 1948, where again interracial dances were salient, and ‘[t]here had previously been trouble at a dance when some of the Irish resented the Jamaicans’ advances to white girls (mainly EVWs on the staff)’ 7. Despite the acknowledgement in each of these cases that the Caribbean workers were not the aggressors, the ensuing NSHC correspondence in every instance included the suggestion that they be transferred elsewhere.

The Causeway Green ‘Riots’

Of the approximately 700 men staying at the Causeway Green Hostel in August 1949, 235 were listed as Poles, 18 EVWs, 235 Southern Irish, 50 Northern Irish, 65 Jamaicans, and 100 English, Scottish and Welsh.

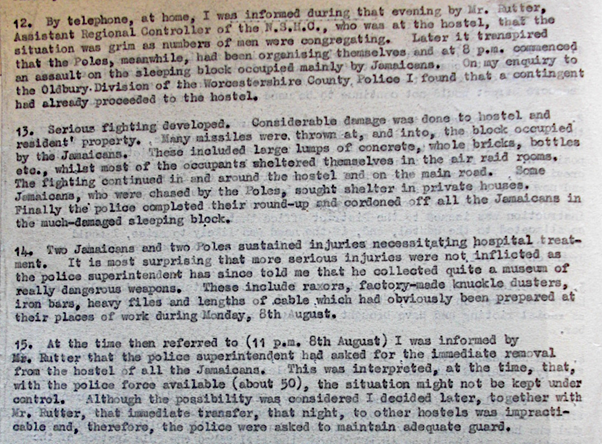

The breakout of violence at Causeway Green on Monday 8 August was preceded by a number of incidents at the hostel. On Wednesday, there was a ‘slight scurry’ between the Jamaicans and Poles after a dance at the hostel. On Friday, there was ‘a more serious affair’ over the attentions of a woman, which escalated to involve ‘a crowd fighting with bottles in the main reception hall’. The Jamaicans then withdrew, only to return ‘armed with miscellaneous weapons’ and ‘throwing bricks etc.’, before the arrival of the police. Some damage was done to hostel property, including broken chairs, tables, window frames and panes of glass. Eighteen people, including a policeman who received a blow to his head requiring stitches, attended the sick bay for treatment. On Sunday, the residents informed the hostel manager that the Poles intended to retaliate in the canteen at midday. The police were called, but, excluding a ‘skirmish’ on the road between three Irishmen and two Jamaicans at 23:00, no incident took place.

The riots began on Monday at 20:00. The report of the Regional Welfare Officer describes the following:

Resisting Racist Evictions

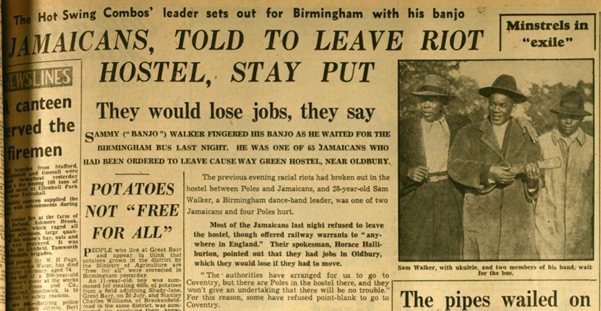

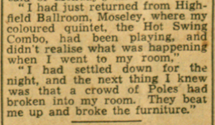

The management, although in general agreement with the police that the Jamaicans should be removed, deemed it impractical at the time, and sought to evict the Jamaicans ‘before the Poles and British Isles residents returned from work’ the following evening 8. However, in the face of this prejudiced response, the Jamaicans displayed an important act of resistance, and as the Birmingham Gazette described it, ‘stayed put’:

The article features a picture of musician, Sammy ‘Banjo’ Walker, one of the 65 Jamaicans who decided to stay. As he described it:

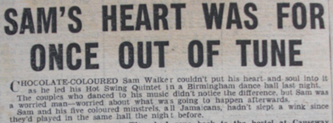

Amazingly, as the Daily Mirror reported too (albeit with the racist opening line ‘Chocolate-coloured Sam Walker …’), Walker still went on to perform the following night at the Birmingham Dance Hall. This shows the story had been picked up by the national press as well:

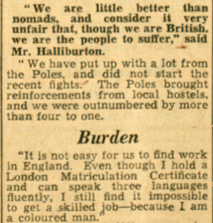

In the Birmingham Gazette story, Horace Halliburton, who went on to write a detailed article the following day, also emerges as an extremely articulate spokesperson.

Introducing Quotas

A quota of 12 black people in NSHC hostels was brought in three days after the disturbance. However, it soon came in for criticism among the organisation’s officials. It was argued that it could potentially damage the reputation of the NSHC ‘if grounds are given for the accusation of colour prejudice’; it was disapproved of for its ‘arithmetic’, as the hostels varied in capacity ‘from over a thousand places to under a hundred’; and it was criticised on ‘policy’ grounds, as it frustrated efforts to direct labour to underserved industries 9.

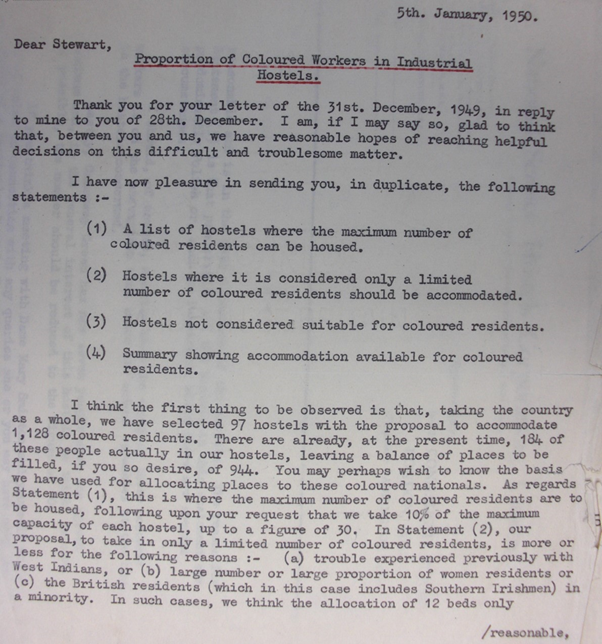

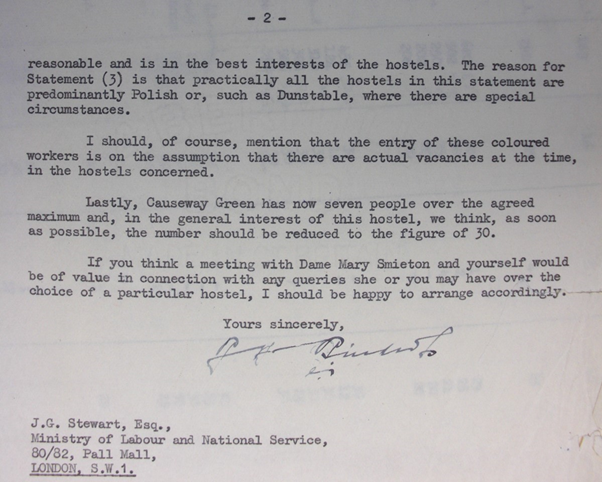

Thus it was expanded on, and the final policy drawn up in the following document was that the hostels could:

- Accept black men ‘up to 10 per cent of the total capacity … subject to a maximum ceiling of thirty.’

- If regarded as potential trouble spots have a lower ceiling of 12 black people, because, ‘(a) trouble experienced previously with West Indians, or (b) large number or large proportion of women residents or (c) the British residents (which in this case includes Southern Irishmen) in a minority.’

- Not be considered suitable for black people at all. ‘The reason for statement (3) is that practically all the hostels in this statement are predominantly Polish …’

In the case of the Causeway Green hostel, which had 65 Jamaicans prior to the riot, and many refusing to move on afterwards, it was clear that 12 was a particularly ambitious number. Therefore official policy was to reduce the number to 30.

Conclusion

The Poles and Jamaicans (and in the case of the earlier disturbances, the Irish too), had in many ways a shared experience of migration, a similar position in many of the least desirable jobs in industry, and a deep feeling of estrangement in a new country. Unfortunately, however, this didn’t seem to lead to any form of class-based comradery, and it seems that a more primeval sentiment – against inter-racial relationships – played a vital role in the unrest.

The reaction of the NSHC, local council and police (united, as all these bodies were, around a wish to remove the Jamaicans), served to legitimise the rioters and, hence, racism itself. Their description of the events as ‘racial riots’ implying a clash of two equally-matched sides, is clearly problematic too, as by their own admission the disturbances largely consisted of Polish residents attacking an outnumbered, by four-to-one, group of Jamaicans.

It’s also important to note that the same concern about interracial relationships did not apply when Eastern Europeans were involved. Drawing on Parliamentary debates from the time, Kay and Miles (1988: 216) point out that the government had a very different view of relationships between displaced persons from the continent and local people, and those of black people and white Britons, and that the ‘replenishment of stock’ and ‘an infusion of vigorous new blood from overseas’ were also important reasons leading to the former’s entry. They write: ‘They were variously described as “ideal immigrants”, as “first-class people, who, if let into this country, would be of great benefit to our stock” and would refresh, enrich, and strengthen “our island population” 10.

The Causeway Green episode and the agitation around the NSHC hostels highlight the essential contradiction that, for black people, ‘it was their labour that was wanted, not their presence’ 11. However, the story also provides an important example of resistance, as the Jamaicans decided to ‘stay put’. They were certainly never passive victims of the attacks or management policy to remove them, and this narrative of resistance in the face of racism, would of course serve as a recurrent theme throughout black British history.

On the Record: 20th Century Migration

There are over 900 years of immigration records available for research here at The National Archives. In our latest three-part podcast series we explore stories of migration in the 20th century.

In this series you’ll hear about major Acts that highlight shifts in policy around migration and citizenship over the past 100 years. We feature the profound and lasting impact of migration for citizens and non-citizens alike throughout Britain, its Empire, and the Commonwealth.

Subscribe: iTunes | Spotify | RadioPublic | Google Podcasts

Notes:

- This blog entry is based on an article by Searle (2013) ‘“Mixing of the unmixables”: the 1949 Causeway Green ‘riots’ in Birmingham’ Race and Class vol. 54 no.3 pp.44-64. An abridged version of the article also appears in the book, Adi (ed.) (2019) Black British History: New Perspectives London: Zed. For a more detailed discussion of the events, see either. ↩

- The major broad-sweep historical studies of the black presence in Britain have not mentioned the incident at Causeway Green. These studies usually describe the events in Nottingham, and then Notting Hill, in 1958, as the first racialised disturbances to take place in the post-war British hinterland, or imply that they were the first incidents of unrest (cf. Fryer (1984) Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain London: Pluto; Hiro (1992) Black British, White British: A History of Race Relations in Britain London: Paladin; Olusoga (2016) Black and British: A Forgotten History London: Macmillan; Phillips and Phillips (1998) Windrush: The Irresistible Rise of Multiracial Britain London: HarperCollins; Ramdin (1987) The Making of the Black Working Class in Britain Aldershot: Gower). Studies of public disorder or ‘riots’, in the 20th century, have also failed to include the incident at Causeway Green, and the other NSHC hostels (cf. Joshua et al. (1983) To Ride the Storm: The 1980 Bristol Riot and the State London: Heinemann; Rowe (1998) The Racialisation of Disorder in Twentieth Century Britain Aldershot: Ashgate; Waddington (1992) Contemporary Issues in Public Disorder: A Comparative and Historical Approach London: Routledge. Causeway Green has not, however, been entirely absent in the literature, and was briefly noted in, Pilkington (1988: 49-51) Beyond the Mother Country: West Indians and the Notting Hill White Riots London: I. B. Tauris; Joshi and Carter (1984: 60) ‘The Role of Labour in the Creation of a Racist Britain’, Race and Class vol. 25 no. 3. ↩

- Cabinet Man-Power Working Party Memo, 30 November 1945, cab 134/510 quoted in Joshi and Carter (ibid.: 55). ↩

- Cf. Fryer (1984); Phillips and Phillips (1998); Ramdin (1987). ↩

- LAB 26/198, 26 Jan 1948 ↩

- Ibid., 9 Dec 1947 ↩

- ibid., 9 August 1948 ↩

- Ibid., ‘Racial Disturbances at Causeway Green Hostel: Jamaicans and Poles’ ↩

- LAB 26/198, 28 November 1949 ↩

- Kay, and Miles (1988) ‘Refugees or Migrant Workers: The Case of the European Volunteer Workers in Britain (1946-1951)’ Journal of Refugee Studies 1(¾) pp.215-216 ↩

- Sivanandan (1982: 4) A Different Hunger: Writings on Black Resistance London, Pluto ↩

Where was the Causeway Green Hostel.I was born in1948 and went to Causeway green infants and Junior school from1953 to1959.I lived with my parents in Cakemore Road

The hostel was on the land where the PDSA now stands on the Wolverhampton Road and as far as I know it spread as far as Brandhall golf club.

I delved a little more into what became of Horace Halliburton (who features in the story of the Causeway Green ‘riots’). Although he lived in Birmingham for a number of years having married a local girl, he returned to Jamaica and eventually moved to the USA. https://www.historycalroots.com/horace-william-halliburton/