Chris Heather writes: For more than 10 years volunteers at The National Archives have been cataloguing a series of Home Office Domestic Correspondence dating from the reign of King George III (HO 42), making the series searchable via Discovery, our catalogue. So far we have covered the period from 1792 to 1805, thanks to our hard-working team.

We are now working on the period from 1806 to 1811, which takes us through Napoleon’s Continental Blockade, the start of the Peninsular War, the construction of Dartmoor Prison, Lord Nelson’s funeral and on through the Regency era with the start of the Luddite disturbances.

All of these events, and other day-to-day occurrences, are recorded in these papers, and we are lucky enough to have an ex-member of Home Office staff volunteering with us. In this blog entry, Carol Kellas highlights the variety and richness of these records with examples from the year 1810.

The past, they say, is another country and Home Office papers from 1810 reveal some aspects of life which seem very strange to us, such as the request for instructions, which came in from the Isle of Wight in August, in response to the number of dead bodies found floating in the sea, having died on board ships in quarantine. Unfortunately we do not know the Home Office response in this case, but more generally the papers reveal a good deal of official concern about public disaffection that arose from revolutionary ideas, and demands for Parliamentary reform.

The most controversial event of the year relates to Sir Francis Burdett MP, a radical and a keen supporter of parliamentary reform who, in April, so annoyed the Speaker of the House of Commons that he was committed to the Tower of London for the remainder of the parliamentary session, and not released until June. (It is a fair bet that the present Speaker would love to revive these powers). Burdett was conveyed to the Tower by the Life Guards who were pelted with stones, two of them being shot but not seriously wounded, and there were riots in various parts of London started by Burdett’s supporters. One unfortunate man, Charles Wright, received a musket ball in the thigh on his way home from work, but compensation was refused.

Coaches were stopped by demonstrators in front of Burdett’s house and men were required to doff their hats on pain of being pelted with mud if they were too slow about it. Military aid to the civil power was required on several occasions to disperse the mobs, and the Home Office used the country’s network of Post Offices to intercept letters to seek information on the state of public opinion (HO 33/1).

The rest of the country was reported to be quiet although there were some reports of the daubing of slogans on walls. General George Don, writing from the Army East Division HQ at Bow, reported on an inclination for people to riot along the left bank of the Thames, from London Bridge to Blackwall. The watermen, those who worked on the lighters, and the shipwrights, were disaffected and apparently prone to revolutionary principles. The people in Shoreditch, Clerkenwell and Spitalfields were ‘bad and ripe for mischief’. The construction of the London and West India Docks had increased dissatisfaction among those who lived on the banks of the River Thames, and tax collectors in Tower Hamlets had been stirring up trouble, while the ‘lower class of Dissenters’ in Ilford, West Ham and East Ham he states could be induced to join a mob. Men flush with cash were saying in the public houses that Burdett had acted like a fool and that others would manage better in future.

Having Sir Francis in custody in the Tower of London caused its dilapidated state to become the object of concern. Houses had been built within its walls; soldiers were allowed to wander in and out at will, and there was a quantity of combustible material stored in the grounds. It seemed unlikely that the Tower could withstand a determined assault from a mob, should it arise, and swift action to strengthen the Tower was demanded.

Meanwhile a more generalised dissension in the countryside found its expression in the burning of hayricks. Landowners and farmers responded by offering rewards and asking for the promise of the King’s pardon for any accomplice who gave evidence leading to a conviction.

In the country at large there was a constant undercurrent of concern about French spies, such as the activities of a Mr Mills of Passy, near Paris, who was reported to be spending a lot of time in the Rochdale mills, Lancashire, apparently observing recent improvements in the cotton manufactories. There was a letter from Birmingham reporting on a man in a pub trying to buy arms for Ireland, and letters from informers, some of them anonymous, providing regular reports of untoward activity or suspicious circumstances across Britain.

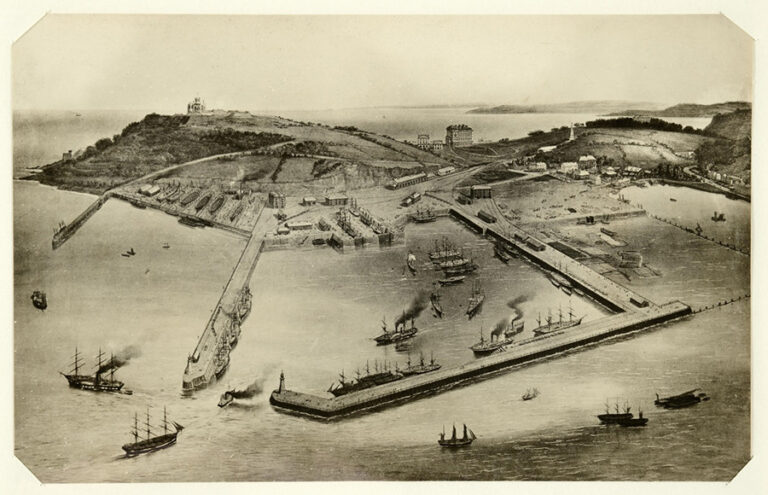

October saw a big row down in Falmouth, Cornwall, involving seamen manning the Falmouth packet ships. These ships carried mail, bullion, private goods and passengers to and from the far reaches of the British Empire, and often the harbour was full of these ships going about their business. The sailors on two ships refused to go to sea on the grounds that their property had been wrongfully seized by Custom House officials. Matters became heated when the men were pressed, or forced, to join the Navy, whereupon the sailors on the remaining packets refused to go to sea and demonstrated on shore. The seamen’s delegates, John Parker and Richard Pascoe, went to London to put their demands to the Post Office but they were imprisoned by the Lord Mayor who did not realise that he had no power to do this. Alternative arrangements for the mails were discussed, including using the town of Fowey instead of Falmouth, 30 miles up the coast, but eventually it all blew over and most of the men returned to work.

Criminal justice matters inevitably occupied a good deal of Home Office time. In July the Transport Office forwarded a letter relating to Thomas Moore, in custody and charged with aiding the escape of two French prisoners of war, General Pillet and Captain Paolucci. Moore claimed to have buried some despatches of a treasonable nature on a cliff top between Bexhill and Hastings and offered to trade these for a pardon. However when taken to the spot he was unable to find the papers, so instead he offered up the names of people in Deal, Dover, Folkestone and Whitstable who were allegedly concerned in helping prisoners of war. The papers record a certain level of scepticism in the Home Office as to the value of his information, and it seemed unlikely that his co-operation would be worth a pardon.

In December, Henry Thomas of Swansea was arrested on a charge of stealing a horse. While in gaol he made disclosures about a murder committed in the mountains of Carmarthenshire about 15 months earlier, and some passing drovers confirmed having seen a body on the hills at about that time. Thomas Prosser, the Acting Magistrate for Monmouth, wanted to offer Thomas a pardon in exchange for his information, but the Home Secretary, Richard Ryder, was more cautious and decided that all necessary enquires had to be made before any pardon could be considered.

The Thames Police Office, founded in 1798, was busy during this period with strikes in the docks and associated disturbances, and in November the East India Company complained that the Thames Police were slack about preventing pilfering from its seagoing vessels at Gravesend. Mr Walsh wrote from Gravesend to say that, in his view, the problem arose from the fact that many of the crew were engaged to navigate the Company’s ships only as far as Portsmouth after which they returned home, leaving them unprotected. There were certain places along the river where stolen goods could be disposed of, and the Thames Police should be able to identify the receivers of these goods at Northfleet, Grays and Greenhithe.

There were several letters alleging harsh sentencing in the courts. Richard Radley was transported for seven years for being in possession of three shirts, and in April Mr Justice Heath was accused of sentencing three men to death at Maidstone for trivial offences. The judge responded rather testily to the effect that he had tried 99 persons at Maidstone and sentenced one man to death for murder and passed the same sentence on Laws, Nicholls and Pernal for robbery. Laws had stolen a plate worth £20 from Mary Wilkins, a poor widow; Nicholls stole two heifers from another widow; and Pernal stole goods worth £40 from the cottage of a man who was out at work. The judge felt that there had been far too much housebreaking in Kent and it needed to be discouraged.

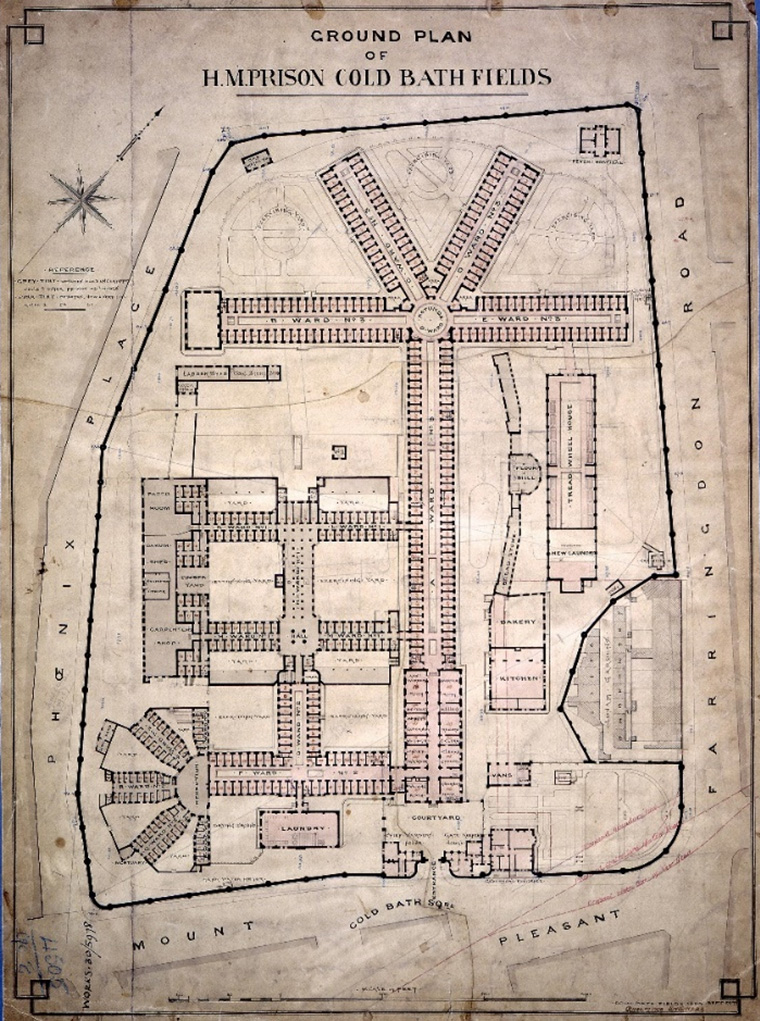

There was even criminality within the heart of the prison system which came to light when a forger, Robert Roberts, was enabled to escape from Cold Bath Fields gaol, apparently with the collusion of Daniel Aris, the Governor’s son.

March recorded a petition from Peter Atkins of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. He had been sentenced to death for stealing goods from a ship wrecked on the Goodwin Sands off the Deal coast in Kent, reprieved and allowed to transport himself for life. Atkins, a Deal boatman, had gone out with others to a stricken ship on the Goodwin Sands which could not be saved. Some of the crew were lost but he helped save the lives of many others. As he was a man of good character, and had served as a petty officer in the Sea Fencibles, the Corporation, merchants and inhabitants of Deal petitioned for clemency, pointing out that Deal boatmen often risked their lives in rescues at sea without any recompense. Putting Atkins to death would not be likely to encourage them. The only objections to clemency came from Lloyds insurers who had mounted the prosecution. Atkins had taken himself off to Rio de Janeiro and was now working as a clerk in the naval stores there. He enclosed a reference from Sir James Gambier, the Consul General, and asked to be allowed to return to England to provide for his wife and five children. The response was that every possible indulgence had already been shown to him and nothing further could be done ‘with propriety.’

Finally, no set of Home Office papers would be complete without complaints from prisoners. In March the convicts on board the Retribution hulk at Woolwich complained about the food, the clothing and life in general, and an investigation was carried out by a Mr Whitbread. He found the allegation that men were forced to go to work barefoot to be false, having inspected all the men and found them to be provided with both shoes and stockings. The allegation that men were punished for throwing bad meat overboard was also clarified. Some meat was indeed found to be bad by the convicts’ own food inspector, and this was returned to the butcher who had supplied it. But two additional quarters of beef were good, although John Woodley and James Campbell had thrown them overboard, for which they were confined to the hulk. A boat had been sent out to retrieve the meat which was recovered, cooked, dressed and served the next day, and was found to be perfectly good!

Obviously the precise circumstances are different, but it is a sobering thought that, despite the passing of 200 years, the Home Office today still deals with complaints over policing, criminal sentencing, prison conditions, riots and disturbances, problems over merchant seamen, clashes in the House of Commons and the recovery of bodies from the sea along the south coast of England.