This blog article is part of the 20sPeople season – a season of exhibitions, activities and events from The National Archives that explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s.

This blogpost will use LGBTQ+ as an umbrella term to describe lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer people across a variety of time periods. These individuals would likely have used a variety of different language to describe themselves in their own life times. For more context around language and LGBTQ+ history, refer to The National Archives’ guidance on Sexuality and gender identity history.

Families come in all shapes and sizes. Same-sex couples now have the right to marry and adopt. Family units are more diverse than ever.

But what about 100 years ago or more?

From 1841 to 1921 we can use surviving census records to focus on people’s home lives and the family units they were living in. In this blog post I am going to look at what census records can tell us about lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer people a hundred years ago, focusing particularly on the newly released 1921 Census records. After all, while the language has changed, LGBTQ+ people have always existed. Their stories can be found on the enumeration sheets of the census, just as everyone else’s can. This blog post will explore the domestic ‘normality’ that was available to some LGBTQ+ people in the past, examining a small selection of case studies from across the country, from London to Sheffield.

Same-sex home lives and family units

In the past, the law criminalised sexual relationships between men, and society broadly condemned same-sex relationships between women. Presenting unconventional gender expression, or identifying as a gender you were not associated with at birth, was not widely acceptable. But despite these legal and social pressures, LGBTQ+ people found their own ways to create family bonds and live in partnership. For some this possibility of a home life might have meant actively having to avoid the law, while others may have just been able to lead their lives in privacy.

Some LGBTQ+ people chose to echo institutions like marriage; the Ladies of Llangollen lived in a loving relationship similar to a matrimonial couple, while Anne Lister and Ann Walker held a ceremony akin to a wedding on Easter Sunday 1834 in Holy Trinity Church, Goodramgate. In the 1920s we see two men describing their relationship in terms of ‘husband’, ‘marriage’ and ‘honeymoons’. The census also shows more complex family units, and demonstrates how same-sex couples worked around the restrictions on their relationships at the time; some have partners who were listed as domestic servants or as boarders. At times this might have been due to a need to hide relationships or a genuine reflection of the roles each other took in the household.

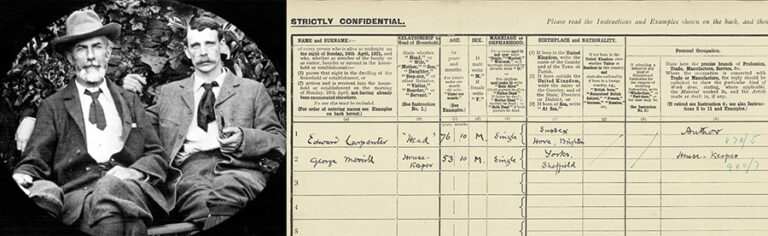

Through the 1921 Census

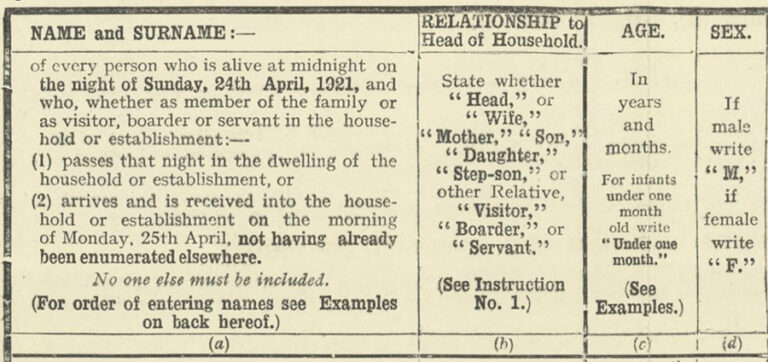

The easiest way to trace LGBTQ+ relationships in the census is to start by looking for people who were openly known to be in same-sex relationships, or to identify as bisexual, in their lifetime. One that we know of is famed author and lesbian, Marguerite Radclyffe-Hall, one of our 20 People of the 20s. Radclyffe-Hall and her lover, sculptor Una Troubridge, were said to have been in a relationship from 1915 onwards. In the 1921 Census the pair are recorded as living together at 7 Trevor Square, Knightsbridge. Troubridge made the census return on behalf of the couple and uniquely listed them as ‘joint head of household’, hinting at their partnership but also showing the equitable nature of their relationship.

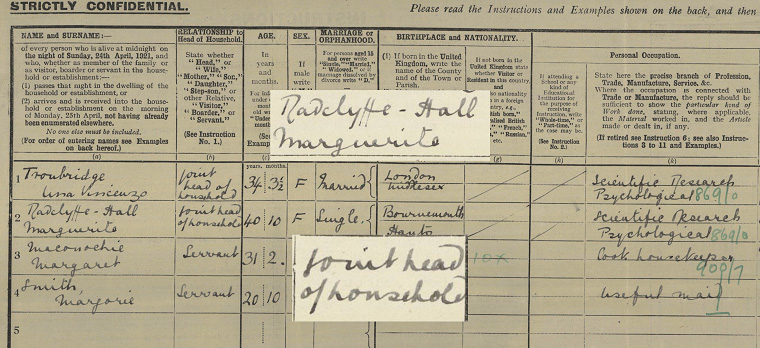

The British painter known as ‘Gluck’ (born Hannah Gluckstein), who worked with the Lamorna artists in Cornwall, was known for their gender non-conformity. The census shows Gluck and their partner E M Craig (known by their surname Craig) living together on the census, listed as ‘head of house’ and ‘boarder’ at Tite Street, London. Both were described as artists. Gluck generally rejected first names and gender prefixes, but submitted this census information under the name ‘Hannah Gluckstein’. This demonstrates some of the challenges of the census at this time; it didn’t generally give the flexibility in the information asked for, for people to define themselves on their own terms. We can see this in the binary gender categories as well.

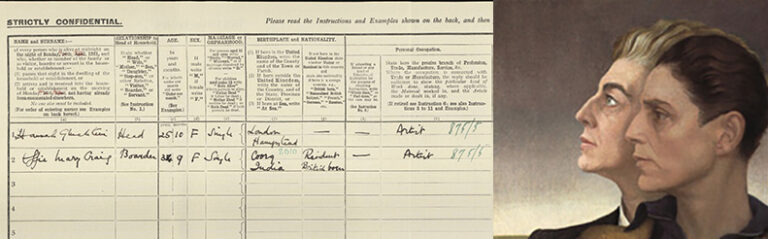

Alternatively, Edward Carpenter, author, free love advocate and pioneer for gay rights, lived with his partner George Merrill after meeting in 1891. Merrill was a working class man from Sheffield who Carpenter had met on a train journey. The two men struck up a deep, life-long relationship, living together at their small farm in Millthorpe, near Sheffield. The two lived as a couple for almost 40 years, as seen across multiple census records, until Merrill’s death in 1928. The census form lists Carpenter as an ‘author’ and ‘head’ of household, while Merrill is listed as a ‘house-keeper’. Did this reflect actual roles at the time or was it necessary to camouflage their relationship in this way? The relationship between Carpenter and Merrill is believed to be the inspiration for E M Forster’s novel Maurice, which depicts a relationship between two men: the protagonist and a gamekeeper.

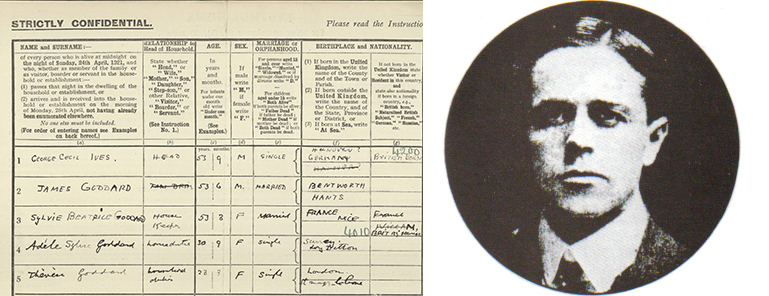

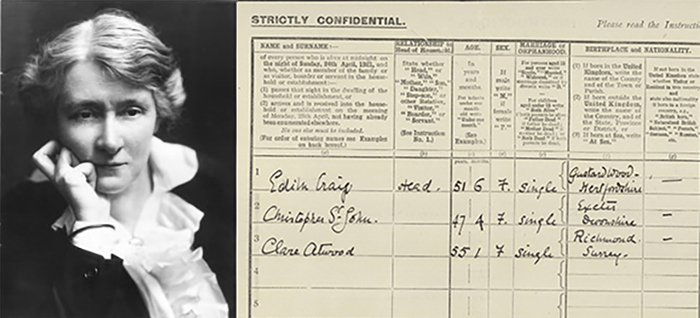

Pages in the census also tell us about less conventional family units. George Cecil Ives, the sexual law reformer, author and poet lived at 196 Adelaide Road, Hampstead until his death in 1950. He lived there with James Godard, the love of his life. Godard also lived there with his wife and two children. Alternatively Edy Craig, the theatre director, ever unconventional, lived in a ménage à trois with the dramatist Christabel Marshall, who published under the name Christopher St. John, and the artist Clare ‘Tony’ Atwood, from 1916 until her death. This can be seen In the 1921 Census, with them all living together at 31 Bedford Street, Covent Garden. It is interesting to note the name given for Marshall in the census is Christopher St. John, presumably an intentional choice of how to present themselves on this official record[ref]Although Edy Craig is the individual recorded as the person making the return on behalf of the household. Catalogue ref: RG 15/652, The National Archives.[/ref]. They later lived together at Smallhythe Place in Kent, cultivating a home life that reflected their values and cultivated their creative pursuits.

Relationship to the head of household

This approach of finding well-known people who we might now describe as LGBTQ+ is logical but limiting, as it highlights well-known examples and omits some of the ‘everyday’ experiences. There are some ways of working around this. A search of the census shows many women living together listed as ‘partners’ in the ‘Relationship to the head of household’ column. For some this would have meant business partnerships, while for others it might have been an indication of a romantic relationship, or a lifelong friendship (many women ended up living together as companions for financial and/or friendship reasons after the First World War). These later two interpretations of the word ‘partner’ particularly apply where the individuals’ listed professions are different, making a business relationship seem less likely. A search of this sort is not enough to prove same-sex relationships, but it can prompt us to question the assumptions we might have about people, ensuring we do not always assume heterosexuality on those we are researching.

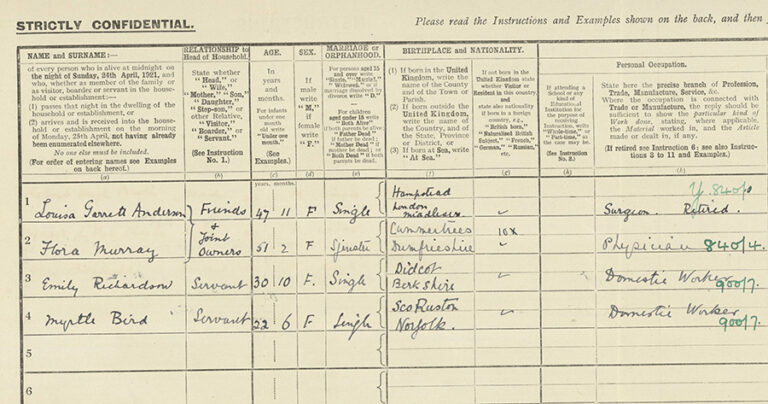

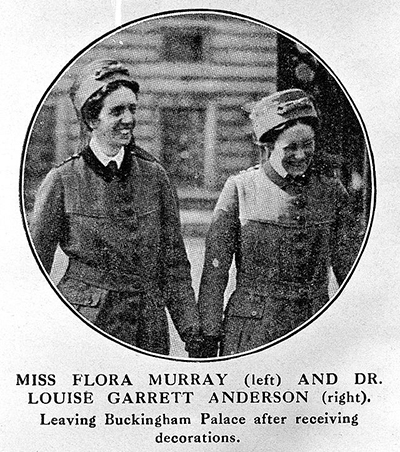

People in the census, particularly women it seems, used a variety of phrases in the column about the relationship to head of household, from ‘joint head of household’ to ‘companions’. It was potentially more difficult for men to actively record these distinctions in the census. Given the law at the time, they had more to risk. Louisa Garrett Anderson and Flora Murray, both doctors, listed themselves as ‘joint friends and owners’ in the 1921 Census. The pair worked intensely together throughout the First World War but they were also believed to be life partners. A shared tombstone memorialises both women, bearing the poignant words, ‘We have been gloriously happy’.

From 1921 to 2021

The 1921 Census has not been available to search for long – these are just some initial findings. I have no doubt that there will be many lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender stories within the millions of entries. What is clear from the small selection of cases uncovered so far is thatLGBTQ+ people found ways of creating and preserving their home lives, their day to day normality, despite the law.

One hundred years on, the 2021 Census became the first to ask explicitly about sexual orientation and gender identity. So much has changed, and yet 100 years later there is a commonality of experience that we can find in the domestic lives of LGBTQ+ people.

Help us find more LGBTQ+ history on the census

We hope to develop this work further to explore more about what these records can tell us about the everyday lives of LGBTQ+ people. Although many of the figures in this blog lived in places outside of London during their lives, this selection is quite London-centric. We hope to come across more of a national spread of LGBTQ+ lives in England and Wales, reflecting rural and more urban areas.

We would love to find lesser-known stories from census records or other archive collections that highlight experiences of people that may have identified as LGBTQ+.

Have you come across LGBTQ+ history in the census? Do share it with us in the comments below.

20sPeople at The National Archives

20sPeople at The National Archives explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s. Accompanying the release of the 1921 Census of England and Wales, 20sPeople shows what we can learn by connecting with those who have gone before us. Find out more at nationalarchives.gov.uk/20speople.