Refugee Week (15-21 June) happens each year. It is a significant opportunity to hear refugee stories and give them a platform.

The aim of this year’s programme is to share information about the reality of the refugee experience. The Partition of British India, which led to one of the largest mass migrations in history, contains countless stories and is a fitting way to speak to this experience. It also saw a vast refugee crisis unfold. And for more than three million people of South Asian heritage living in the UK today, Partition has a very personal relevance. It is a story that still impacts many of them, both in seen and unseen ways.

We have at The National Archives an unparalleled collection of files relating to Partition which often capture in graphic detail what happened. One such file contains a letter from 25 August 1947, from the Deputy High Commissioner in Lahore (Mr Hugh Stephenson) to the High Commissioner in Karachi (Sir Laurence Graffety-Smith). The correspondence describes the extreme violence that erupted very shortly after the announcement of the creation of the two new nations of India and Pakistan:

‘We reached Kasur and asked a young Indian Baluchi Captain whether anything had happened there. There has been a massacre on the station, in the town and surrounding village, in part of Muslims, in part of others, and the two lots of refugees were at the station. What he described as a corpse train was due in. He gave us an escort and we went to the station. There were several British officers there who thought us mad to be out unarmed but who otherwise were friendly. The sight was extraordinary. On one side was a train for Hindustan packed with Hindus and Sikhs with hundreds on the roof. On the other was a Muslim train for Pakistan. In the middle was the corpse train.’

Catalogue ref: DO 412/416

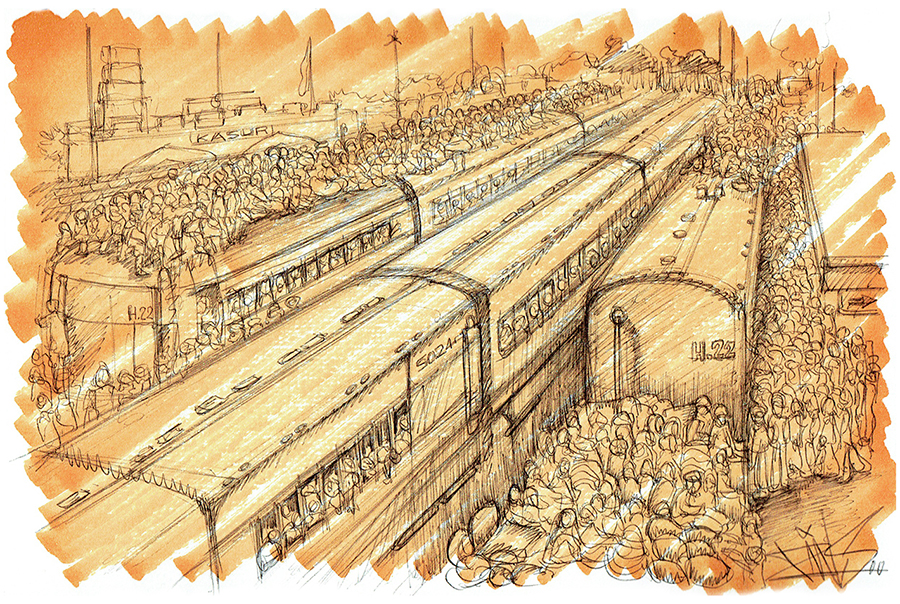

For the many millions forced to relocate, trains became a potent symbol of the Partition experience. Trains provided ideal targets: often overloaded and easy to ambush. Tensions on all sides were increasing as a result of disaffection with the decision to divide the Panjab. Non-state actors*, for example those allied to political or religious organisations, took it upon themselves to take violent action. Attacks by one community on another fuelled revenge attacks.

Partition violence has been referred to as a kind of ‘madness’ that took people over. But ‘madness’ does not do justice to the very systematic and clinical way in which the killing was conducted. Knowledge of train timetables, and collusion with partisan or corrupt officials, meant gangs knew when to strike.

The height of the attacks on trains was between August and October 1947. The severity of the violence stands out. Former soldiers who had served in the Second World War were able to use their training and their contacts to access arms and carry out attacks.

Partition meant seeking refuge in the face of violence or confronting the impending threat of violence; it meant people literally fleeing for their lives to seek out relative safety. The Partition of British India and the resulting refugee story is a story of people finding safety, and trying to remake their lives often in the face of great adversity.

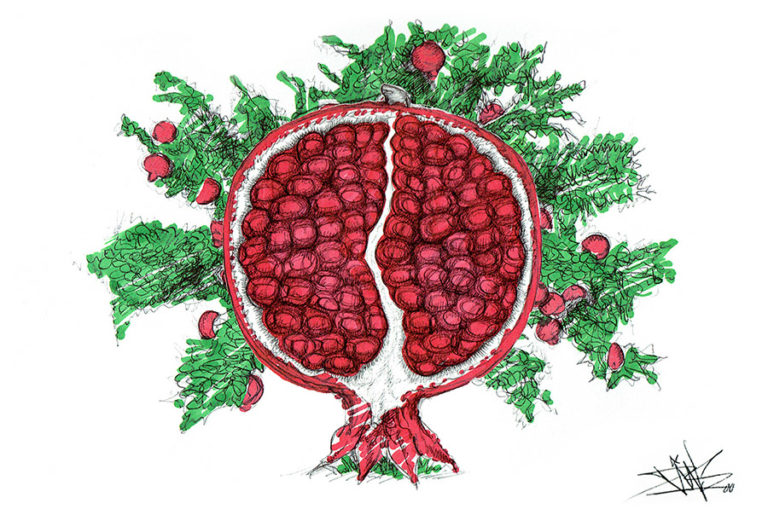

As part of our contribution to Refugee Week, the Outreach team at The National Archives has been working with the artist Pins and the writer, historian and lecturer, Raj Pal, to reflect further on these refugee stories. Each in their own way has responded to the brief. Pins has drawn two sketches – one inspired by the account of the train massacre from our collection, the other in response to what Raj has written of his own family’s experience.

‘But the expulsion we experienced,’ she explained, ‘was so sudden that there was no time to take anything. I could not even take my precious doll that your uncle had bought for me during a trip to the grain market a few years earlier. Oh, how that man, your uncle, spoilt me, his baby sister.‘

Raj’s story ‘The Pomegranate Tree’ in very moving and lyrical tones expresses the terrible impact Partition and the ensuing refugee crisis has had, not just on the generations that experienced it first hand, such as his mother’s, but also on their children. His story is ultimately one of hope and reconciliation.

Download ‘The Pomegranate Tree’ story PDF

Pins’ artistic response speaks for a younger generation of people of South Asian heritage, who remain fascinated by their parents’ and grandparents’ histories and are finding out and responding to this story in diverse and creative ways.

My own family’s journey (see links below) to safety in India in 1946 was also one of forced migration; however, they were the relatively lucky ones. They were able to arrange their escape in time, and avoid the fate of the many millions who were forced to migrate at very short notice, and those who became victims of unspeakable violence:

‘We were the lucky few who did not lose any family members in the riots around Partition; we were the lucky few who managed a safe exit from the riot-affected cities and towns; we were the lucky few whose women did not jump into wells to protect their honor… But were we really lucky enough? We had witnessed partition; we had experienced that sense of being suspended in time, longing for our land and home.’

In keeping with our Outreach role, we also commissioned the artist Pins to create a downloadable, interactive artwork which readers may want to use as part of a colouring activity. Or readers may want to take inspiration from Raj’s story and write their own stories about what Partition and the ensuing refugee crisis may mean for them.

*an individual or organization that has significant political influence but is not allied to any particular country or state.

Additional resources

The Pomegranate Tree (mp3 audio) – Listen to Raj Pal reading an extract from the story, ‘The Pomegranate Tree’.

Down Memory Lane – This blog post, written by a member of my family independently of The National Archives and or our records, is a first hand account and adds to the spirit of my blog post.

The Road to Partition 1939-47 – The National Archives Education resource on Partition.

Panjab 1947 a heart divided – The National Archives’ Panjab 1947 online exhibition.

On the Record: Refugee Stories available now

To mark Refugee Week we have made a bonus episode of our podcast On the Record at The National Archives, which is now available on the Archives Media Player and on podcast listening apps. In this episode my family’s experience of Partition features alongside archive documents and personal stories related to other refugee movements.

Subscribe: iTunes | Spotify | RadioPublic | Google Podcasts

You can also catch up on previous series in which have uncovered the true stories of famous spies and looked at protest – from the medieval Peasants’ Revolt to Black power in the courtroom. Most recently we have read famous love letters, and between the lines of less obviously romantic records, to discover the love stories of everyday people from the last 500 years.