I was interested in some of the wider questions that were raised over the spring this year on the size and scale of the civil service. One of the straw-men that was set up was that the UK government, at the height of Empire, ran everything with 4,000 people, all of whom could be fitted neatly into Somerset House. With a little help from the team here (in particular Ed Hampshire), we thought it might be useful to assess this in some more detail.

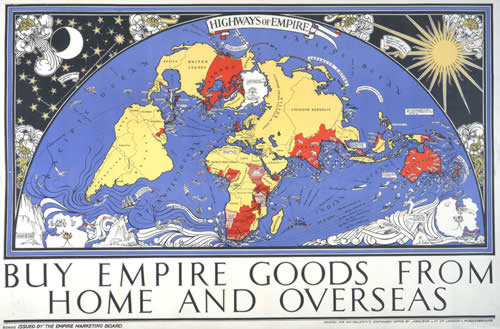

Empire Marketing Board 1927 'Highways of Empire' (Catalogue ref. CO 956/537 A)

Starting with civil servants in Whitehall, 4,000 is about right for the interwar period, but too high for the 19th century. The central government departments were all very small until the First World War. For example, the Foreign Office had around 100-175 staff (including doorkeepers, porters etc.) up to 1914. The Admiralty had around 70-80 well into the mid-19th century.[1*] Four government departments (Colonial Office, Foreign Office, Home Office, India Office) were all housed in the building that now only houses about a 1/3rd of the staff of today’s FCO (Charles Street).[2*]

However, up to the early-mid 19th century you could argue that central government was really only about the armed forces, the court and the central co-ordination of revenue to pay for them. Most domestic policy – education, health relief, local justice etc. – were administered and largely paid for (or not) by local communities. Further, note that UK population according to the 1911 census was roughly half of our present population.

However, most civil servants did and do not work in Whitehall. Customs, Excise and the Inland Revenue staff were (and are) all civil servants. As a rough guide, in the mid-19th century just the Excise would have had at least 2,000 staff across the UK, with probably double that in the Customs at the same time.[3*] The workers in the Royal Dockyards and the Ordnance factories were all industrial civil servants until they were privatised in the 1980s and these were enormous concerns as far back as the late 17th century – probably the largest industrial employers in the country until the early 20th century. For example in 1780 Portsmouth Dockyard alone employed 2,400 workers (excluding salaried staff and short term hires which might have taken the workforce over 3,000), and there were at least 8-10 Royal Dockyards at home and abroad in this period.[4*] The numbers were similar at Portsmouth 80 years later.[5*] There would also have been employees of the Office of Works and the predecessor bodies to the Crown Estate which was and is a major landowner.

Taking names of public officials listed in the Imperial Calendar at selected dates we get the following approximate figures: 1832 – c. 8,000, 1898 – c. 14,000, 1920 – c. 24,000.[6*] However the Imperial Calendar would not have listed industrial civil servants – so these numbers can be taken to include only Whitehall and the various revenue collectors.

In addition, those who administered the Empire on the ground were not civil servants. Members of the colonial service were actually employed by the relevant colonial government they worked for, not the British government direct. The administration of the empire was undertaken by a relatively small number of officials but this was partly because British rule was often ‘indirect’ working through local elites who did much of the actual day to day governing, and with the implicit threat of military intervention if there was trouble.[7*] British rule of the interior of Africa was relatively late in any case and only lasted for a 60-70 year period between the scramble for Africa in the 1880-90s and de-colonisation the 1950s-60s. As a very rough guide c. 1,800 colonial servants are listed in 1874 and about c. 4,500 in 1927.[8*] However, this excludes the large number of locally employed staff (drivers, policemen, prison guards etc.), who numbered more than a couple of hundred in Hong Kong alone at the turn of the century, and probably many thousands across the empire.[9*]

British diplomatic representation abroad would have been much lower in the 18th and 19th centuries largely because there were many fewer nation states. In 1887 the UK had diplomatic or consular representation in 50-odd countries (including the major states making up the newly created German and Italian empires).[10*] It is probably three or four times that today. c. 3,000 active or retired diplomats or consuls were listed in the same year.[11*]

Total figures are extremely difficult to come up with, but we would suspect that it would have been at least 40,000 in the UK at the turn of the 19th/20th century. Given the work of the armed forces in the administration of Empire, it’s probably fair to include the armed forces and local colonial administration. In which case, the 4,000 is probably out by a factor of around 30.

Excellent and interesting article. Without Keynesian economics and the introduction of central government until the late 1800s Treasury operated with a ridiculous small staff in the Treasury Building, now known as 70 Whitehall and the home of the Cabinet Office. It would not be until after the bomb damage in 1940 and increased staffing for the Second World War that Treasury would have to move into GOGGS (Government Offices Great George Street) although increased pressure during te First World War led to the Treasury reorganisation of 1919 and only in the 1950s that Treasury delegated its powers to a certain extent that less staff were needed. It was at this time that Government tried to isperse departments outside London, eg the Ministry of Pensions to the Blackpool area but was hampered by the lack of local accommodation.

Until the implementation of the Heathcote-Trevelyan report in 1855 on the civil service where people were appointed on meit and not just because they had relatives who worked in the civil service. With the exception of charwomen no women were employed until about the 1870s when typewriters arrived, it would not be until the 1950s that departments employed women messengers and not until after the Second World War that the Marriage Bar was abolished in non-service departments. What can be a surprise is the fact that Treasury staff worked between 10 am and 4pm and had a brandy allowance. The case of Baileys (Malta) Ltd for work previously done by the Admiralty in the 1950s lead to problems and whilst a lot of ‘Empire’ staff (including British Embassy/Consulate staff ) were locally-employed staff the issues with their pay and allowances post-independence were often an issue for central government here in the UK to sort out.

I think you miss several points. The Imperial Calendar does not always include all staff – it misses out clerical staff, messengers etc.

And more importantly – what was expected of government was much less. In 1800 for example, to take a minor example, nobody considered systematically preserving government records through a national archives. The Public Record Office was not set up to 1837, and arguably systematic record management functions did not begin until 1958 and now there is a dedicated team of 600…

Certainly government administrataion in the 19th and early 20th century was not on the scale it is today, despite efforts to cut the civil service down. On the matter of records administration whilst records management functions in most departments did not start until 1959 Treasury has had systems from 1782 which in theory should have worked well but failed and it was not until the 1820s that matters came to a head and was rectified. In fact Treasury were instrumental in getting the 1958 Act working, including replacing the head of the PRO in 1954. The Imperial Calendar didn’t include everyone but it included more staff than currently is available. Whilst TNA currently has around 600 staff a lot of these functions would be to support IT in a digital age and researchers which are a recent and growing area. Indeed it is the case now that with more staff we have less records transferred to TNA, more files going missing at transfer and departments not meeting the 30-year rule than was the case 20 years ago. Of course at that time it was the Public Record Office and not a ‘national archives’ which annoys those of us with Scottish ancestry, where we have have our own archive in Edinburgh.

I think that without civil servants the country would soon come to a halt, for example how our Embassies and Consulates help people when they have been bereaved or a natural disaster has occured. If you took all civil servants away then there would be few services left (including The National Archives), politicians don’t run the economy themselves and without civil servants the UK would not function.

The country would come to a halt? In what sense? I think we have, over the years and decades, become more and more conditioned to think that we need government to spend our money for us. Yes, we would suddenly not be getting all these “services”, but on the other hand, working people’s discretionary income would suddenly increase by 20 -100%…

Without the civil service, there would be no health provision, state or higher education, law and order, national security (armed forces, MoD, Royal dockyards etc), state funded research into health, the sciences etc, law and order, customs and excise, immigration control, environmental control, the list goes on. Those private sector workers in the very short term, would run into trouble very quickly without the civil service.

[Comment edited by moderator in line with guidelines http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/moderation-policy/ ]

Actually, the figure now is more like 420,000 FTEs in the Home Civil Service, EXcluding the police, the armed forces and the NHS. The foreign service and Northern Ireland are excluded from this figure too.

What sort of backgrounds were the civil servants from? Where they all upper class or middle-middle class like children of teachers and vicars etc?

Seriously. well observed . Thank you.

Until 1854 civil servants were often appointed through patronage (in the early 19th century they received fees that had been collected) and were sometimes related (the Hamiltons at the Treasury) are an example, but as a result of the Northcote -Trevelyan report of 1855 and the setting up of the Civil Service Commission this began to change as long as they were British and had passed the Civil Service examinations, there were of course no women (apart from cleaners/charwomen until the late 19th century).

It was likely that a number of civil servants would have better education than others but it would not be until around the First World War that the Civil Service needed more staff to do administrative jobs rather than making high-level decisions and the qualifications would have been set at a lower level of ability to reflect the jobs that they were being asked to do..

So the conclusion remains the same: a vast empire was controlled with only a small fraction of the number of civil servants we have now.

PLEASE NOTE: Due to the age of this blog, no new comments will be published on it. To ask questions relating to family history or historical research, please use our live chat or online form. We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.