I was quite pleased when I was given the opportunity to contribute a post to the ‘My Tommy’s War’ series as it gave me a a great excuse to resume some research my family started a decade ago.

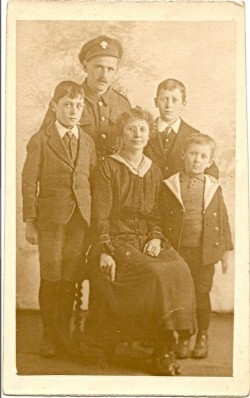

Frederick W. King and family c. 1918 (from private family collection)

I’m not sure when I first found out that my Great Granddad King, my mum’s paternal grandfather, was killed in the First World War. It’s one of those things that it feels like I’ve always known. I remember taking his medals in to primary school to show the class when we were studying the world wars. As a child I felt sad that my lovely grandad, who was just six years old when his father died, had never really known his father. Some years later my mum showed me a precious album of photographs of the King side of the family which featured the photograph on the left. It shows my great grandparents with their three sons. My granddad, the youngest, is on the right. We think it was taken shortly before great-granddad went overseas and I think you can see the fear and worry in their faces. My mum had learned some details of her granddad’s story from her grandmother. She knew that before the war he worked as a bus conductor and was involved with the Labour Party. She also knew that he was injured while serving abroad and that her grandmother had visited him in hospital in the UK before he died. We were keen to try and find out more. This is the story of how we, two amateur family historians, researched our Tommy’s war.

Our starting point was the details provided on the medals. Great-granddad was awarded two medals: the British War Medal and the Allied Victory Medal. The details impressed on the rims of the medals confirmed his name: Frederick W. King, his rank: Private, his unit: Royal Fusiliers and his service number: GS/36785. Shortly afterwards my mum visited The National Archives (then known as the Public Record Office) and obtained a copy of his medal index card. Unfortunately, the index card did not provide any further useful information and our research stalled.

Several years later I came across the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) website. This excellent resource provides a searchable database of the names and places of commemoration of members of the armed forces who died during the two world wars. I was thrilled when I found Frederick’s record as it included some information previously unknown to us. It revealed that he was a member of the 10th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers, the names of his parents, his address and the date he died. We were surprised to discover that he is buried in Carlisle as we have no other connections with that area of the country. However, the general information about the cemetery provided on the CWGC site explains that Carlisle was the location of the Fusehill War Hospital so we assumed that Frederick must have died there. My great-grandmother must have left her three young sons and travelled many miles during wartime to be with her dying husband.

The details provided on the CWCG website also helped us research Frederick’s life before the war. As Frederick King was a fairly common name in England in the late 19th and early 20th centuries it had been difficult to find him in most records. Knowing the names of his parents helped greatly with narrowing down our search. At that time the 1841 to 1901 censuses were available online and through some careful searching we found him in the 1891 census, aged 10, living in Fulham with his parents. By 1901 he was still living in Fulham with his parents and his occupation was listed as wood working machinist. His father’s occupation is listed as omnibus driver which was interesting to us given Frederick’s later job as a bus conductor.

We also searched the Ancestry website for Frederick’s First World War service records. Unfortunately, they were among the 60% which did not survive the Blitz. Sadly, this means that we do not know the date he joined the army, any details about his training or when he travelled overseas.

Birth and marriage records ordered from the General Register Office also helped us fill in more details of Frederick’s story. Frederick married Kate Bailey in September 1905 at Fulham Register Office. The marriage certificate revealed that both bride and groom were living in Fulham at the time and Frederick’s occupation was listed as ‘Messenger (Private)’. Birth certificates obtained by my mum and her cousins informed us that their first child, Frederick Cecil King, was born in 1906 in Kate’s home village of Bottesford, Leicestershire and their second child, Edwin Francis King, was born in Marylebone, London in 1907. Edwin’s birth certificate lists Frederick’s occupation as ‘Mechanical Engineer’. By the time of the 1911 Census, Frederick, then aged 30, Kate, and their children were living in Chesterfield. Frederick’s occupation is listed as ‘Coal Miner (Hewer)’. Their last child, my granddad, John (known as Jack) was born in Chesterfield in 1912. At some point between 1912 and 1918 the family moved to Seymour Gardens, Twickenham and Frederick began working as a bus conductor. These details seem to paint a picture of a man who didn’t have a trade and never settled in an occupation but did whatever work was available to provide for his young family.

In preparation for writing this post I did some research into the Battalion in which Frederick served: the 10th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers. Through some quick internet searching I discovered on the very interesting and useful The Long, Long Trail website that the battalion was originally a ‘pals’ regiment formed of men who worked in the City of London. As a result it was nicknamed the ‘Stockbrokers’. I also discovered that the Battalion originally arrived in France in July 1915. I also looked at The National Archives’ research guide on British Army medal index cards 1914-1920 which explains that the fact the ‘Theatre of War first served in’ box on Frederick’s medal index card is blank suggests that he first went to France in 1916 or later.

Also, while writing this post I applied to the General Register Office for Frederick’s death certificate. The certificate confirmed that he died at Fusehill War Hospital, Carlisle, and recorded his cause of death as ‘Gas Poisoning (Shell) Bronchial Pneumonia’. His widow Kate was the informant.

In the knowledge that Frederick was gassed I decided to look at the war diary of the 10 Batallion Royal Fusiliers in WO 95/2532 to try and find out when and where he was injured. Helpfully, the war diary has been digitised and is available online. The diary described in detail a heavy gas attack suffered by most companies of the batallion on 11th May 1918 while they were staying in the village of Foncquevilliers, Northern France. The diary entry reads:

FONCQUEVILLIERS was shelled in the evening, very heavily with H.E. and Gas Shells, mostly gas. Bombardment started at 7.15 p.m. and was very heavy until 8.30 p.m. when it lulled somewhat but the guns (E) kept up intermittent shelling all night. It is estimated that 10,000 shells fell on FONCQUEVILLIERS and in retaliation we fired 2,100 rounds.

The Commanding Officer, 2nd-in-Command, Adjutant and Medical Officer together with 18 other officers and 300 O.R. went down gassed in the early morning from 2 a.m. onwards.

I wondered whether Frederick was injured in that incident so decided to check how long it typically took for soldiers to die after being gassed. The Wikipedia article on Chemical weapons in World War I suggests that victims sometimes took four or five weeks to die after being exposed to mustard gas which is just a few weeks more than it took for Frederick to succumb to his injuries. I could not find any mentions in the diary of major gas attacks between 11 May 1918 and Frederick’s death on 1 July 1918 so I concluded that he either died a very long and painful death in military hospital or that he was exposed to gas in a smaller incident.

My great-granddad’s story is terribly sad. It was upsetting to read that he experienced the horrors of front line trench warfare and then died a painful and unpleasant death. However, he left the legacy of his three sons which is more than can be said for the many unmarried men who died. The fate of the women left widowed is another topic worthy of research. Frederick’s widow, Kate, continued to live in Twickenham where she became heavily involved in the co-operative movement and left wing politics. After her sons left home she lived alone, being visited often by her many friends and family, until her death at the age of 91. The many interesting stories my mum tells about her ‘Nanny King’ have made me think I might like to do some research into women in left-wing politics in the mid-20th century at some point.

Frederick W. King - War Grave - Carlisle, UK

I would still like to find out some more details about Frederick. I would like to see the trench maps to discover where he may have fought and I would like to find out more details about Fusehill War Hospital. I would also like to find out how typical it was for a married father of three in his late 30s to be assigned to a front line infantry regiment. Frederick certainly does not fit the stereotype of a very young man sent off to war.

A few years ago my parents visited Frederick’s grave in Carlisle. Some of her cousins have also visited. My mum was pleased that her grandfather was at rest in a peaceful and well-maintained cemetery. She took the picture on the right of his grave. I hope to visit it myself later this year to pay my respects to ‘My Tommy’.

A lovely story – it inspires me to get writing about my WW1 soldiers – I’ve got lots of bits and pieces but haven’t tried to put many of them together into a narrative.

barnsleyhistorian.blogspot.co.uk Watch this space!

Thanks for your comment. I’m pleased you found my post inspiring. Good luck with writing up your WWI soldiers’ stories.

Very interesting article. Very similar story to my Great Uncle who was gassed at the Battle of Loos in 1915 and died approx 5 weeks later at a miltary hospital in Devon. It was always a mystery how a WWI solider came to buried in England, I often wonder if his wife and children were able to visit him. Some really useful tips on the research you’ve done (which will be a big help!). I also found some useful info on the British newspaper Archive. Thanks Tony

Thanks for you comment. There must be a vast number of UK families with similar stories to ours. I’m glad you found my research tips useful and thank you for reminding me about the British Newspaper Archive. I must find some time to investigate the BNA collection as part of my further research. Good luck with your research!

There are a few other places to look – I can’t immediately find him in Soldiers Died in the Great War, originally a War Office publication which, as its title suggests lists Britihs soldiers who died in the Great War – though not all of them. Digital versions are available via Ancestry and FindMyPast, and the library at Kew also has a hard copy. This often gives further details of service comapred to th CWGC site, listing units and service numbers prior to a man going overseas. The Medal Index Card only shows the units with which a man served after going overseas – he may have trained with an entirely different regiment prior to being posted.

There are a few more clues in the infomratin you already have. The GS prefix to his number shows he was a war time “General Service” enlistment, rather than having joined up before the war, in the Royal Fusliers and a cluster of county regiments from the south-east of England they used this GS prefix to separate out the wartime enlistments from regular enlistments which used the L prefix (a man could still sign up as a regular during the war, those men would still receive the L prefix, and the prefixes were sometimes dropped in common usage. Note also that for someone in the Royal Field Artillery, an L prefix indicates enlistment into a locally raised unit – the artillery equivalent of the more famous Pals Battalions of the infantry. Some London Boroughs raised artillery batteries in preference to infantry battalions, Wimbledon went for artillery while Wandsworth and Battersea each went for infantry). In King’s case this also confirms that, unsurprisingly given his previous employment history, he was not an early member of the Stockbrokers’ Battalion – they were issued numbers with the STK prefix.

It doesn’t appear you’ve looked at the medal rolls themselves. His medal index card contains the roll reference for his medals, TP/104B12 page 1285, you can cross-reference this with the catalogue descriptions in WO 329 and quickly discover that the relevant medal roll is now held as WO 329/766 (I did a search in Discovery for WO 329 Royal Fusiliers TP/104B12 – a few hits came up, then it’s just a matter of double-checking the page ranges within each). In this particular case it probably won’t add much, but it might just give the date he went overseas, though this is generally rare for rolls other than the 1914 or 1914-15 Star (though some rolls are more detailed than others, the London Regiment rolls are often very detailed for example).

Though his own records don’t appear to survive, it can be worth hunting for men with nearby numbers, in the Medal Index Card search put 367* into the number box and “royal fusiliers” into the Corps box and see what you get. SOme will be false positives because the number is actually for service in a different unit, but you should be able to construct a list of men with similar numbers in the Royal Fusiliers (you may also get some with the L prefix which you should disregard), then search for service records and see if you can establish any patterns – I used this technique to try and establish when a man was transferred from the East Surrey Regiment to the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. Sometimes simply not enough records survive to make this work, and sometimes there’s no obvious pattern. Broadly speaking service numbers were issued on enlistment (or transfer into a regiment), in chronological order, but like most things in the British Army, there are always exceptions to the rule.You mention that he doesn’t really fit our preconception of what a First World War soldier looked like. His age and marital status suggest he was perhaps most likely to have been a conscript or possibly enlisted under the Derby Scheme (this was a sort of halfway house to conscription where men could agree to serve and joined the army reserve, but were usually not called up for active service immediately – while they were awaiting call up they wore an armband with the Royal Arms on, this could be seen on one of the teachers in last night’s episode of The Village” – they were divided into groups, based on age and marital status, generally the younger, unmarried men were called first – basically the same grouping system was used for conscription too. Those who enlisted under the Derby Scheme retained some choice as to the unit they joined, conscripts were assigned to units based on need and ability.). You can find out more about both the Derby Scheme and conscirption on the Long, Long Trail.

However, some older men did join up immediately (for example I’ve researched one man called Harry Jones who was already over 40 at the outbreak of war, but joined up before the end of 1914), often as they were less fit they were assigned to Garrison Battalions initially, either home-based or in places like Malta or Gibraltar – as those did not count as theatres of war, service in those locations did not qualify for the award of Stars. As the war went on, and the need for manpower became more acute, medical classifications were relaxed and more of the older men found themselves in the frontline.

David, thank you for posting such a detailed comment. It’s certainly given me some ideas about other sources to use to expand my research. I assumed that Frederick had been a conscript because of his age and marital status and because all the evidence seems to suggest he went abroad late in the war. I also figured that he wasn’t one of the original ‘stockbrokers’ which your knowledge of the prefixes confirms. I will certainly try your tip of looking for service records of other Royal Fusiliers. Thanks again!

Hi

I run the Henham History website in Essex and we have a war memorial in the church which has inscribed Frederick King. Whilst researching the other names, it appears that it was family members who put it up, do you know if your Frederick having any relations in Henham. If you want to verify my request the page is:

http://henhamhistory.org/HenhamHistoryWarMemorials.html

Thanks

Dear Nina,

As far as I know my Frederick King did not have any relatives in the Henham area. His family was originally from Dorset and settled in London in the mid-19th Century. I have not found any evidence of family living in Essex.

Good luck with your search.

Claire

No problem (and apologies for all the typos that I missed!). When the record’s gone it’s all about building up as much circumstantial evidence as possible.

Others have mentioned the BNA, Richmond library service will also hold copies of the local papers from the time (though reports on individual soldiers tend to dry up during the course of the war, particularly after conscription). As he was brought back to the UK there might be some mention of him. Also, since he was last known to be living in Middlesex, it will be worth checking MH 47 (currently being digitised – blogs passim) to see if he applied to the Military Service Tribunal for an exemption from conscription.

I knew that at some piont I’d taken a photo of the roll of honour in St Mary’s Church, Twickenham, and I stumbled across it while looking for something else on my computer last night, I’ve now uploaded it to flicker. As you will see it includes a Frederick King, doing a quick search on the CWGC site for surname King, First World War and additional information Twickenham suggests there are no other Frederick King’s associated with Twickenham in their records (though family didn’t fill in additional information in all instances).

This roll of honour is read out every year in the evening service on Remembrance Sunday (the service earlier in the day I think focuses on the memorial in the churchyard, which doesn’t have names inscribed on it).

Hello, First of all I would like to thank Claire who on behalf of our family has done a marvellous job in documenting Frederick’s story. Claire is my 1st Cousin 1x removed and I am very proud of her. I have read her blog so many times particularly at this time of year and it always chokes me up. The posts have all been very interesting over the last couple of years, however I would just like to comment on one with regard to the Memorial in St. Mary’s churchyard in Twickenham. In fact the memorial does or did bear the name of a Frederick King which is reflected on the plaque within the church, I have a photo which I took there a few years ago complete with Frederick’s Great, Great, Great Grandsons and Great, Great Grandson and the name of Frederick is displayed. I will post the photo on flicker when I find out how to do it!!

I think the churchyard memorial has been restored since my original comment, and the names re-engraved, they were rather badly worn, which is why I initially thought there weren’t any.

i like it