The recent unveiling of a memorial at the National Memorial Arboretum at Alrewas, dedicated to those who worked in British coal mines during the Second World War, was another reminder of the often unsung sacrifices made during wartime. By late 1943 coal stocks were running low and in order to ensure that the war effort could still be fuelled, the Minister for Labour and National Service Ernest Bevin was charged to enhance the mining labour force.

Bevin Boys - Training, Feb 1945. By Ministry of Information Photo Division Photographer (Public domain or Public domain), via Wikimedia Commons

Bevin decided that a ballot amongst men aged 18-25 would be the fairest and most sensible way of selecting miners, and that the selection group should be as wide as possible. As Lord President of the (Privy) Council, though, it was Clement Attlee, Deputy Prime Minister of the wartime coalition, who circulated the Cabinet memorandum that forwarded the idea (CAB 66/43/31). Ballotees would attend a four-week training session, after which they would work in mines, in physical roles supporting miners (they wouldn’t actually mine the coalface).

A BBC Archive programme for Radio 4, originally recorded in 1983, includes personal recollections of experiences in the mines. What initially struck me when listening to the programme was what one contributor explains regarding the initial shortage of miners: that despite the horrors of war, so many people who worked in mines had volunteered for life at the front. Life and employment in mining communities was tough, particularly before the post-war introduction of safety measures, and perhaps there are are not many more eloquent indicators of that than people actively electing to sign up for battle rather than stay (although one should acknowledge that many might have felt fighting on the front was a more obviously active engagement in the war effort).

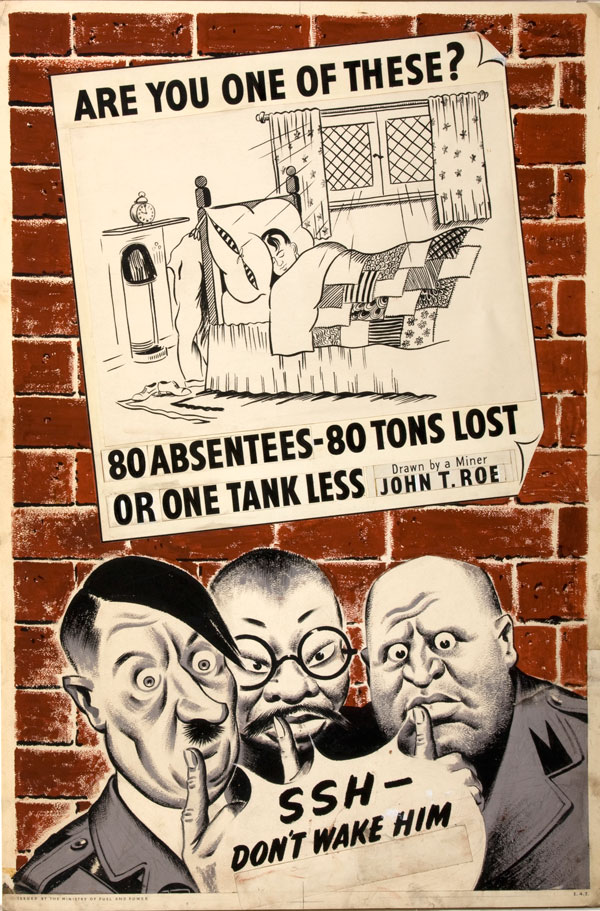

The programme goes on to explain how harsh the experiences for those who became known as Bevin Boys endured. Their equipment was sparse (a helmet and one pair of steel-capped boots – paid for by themselves), the work as ever was dangerous (one fatality was recorded), and absenteeism was punished by a 30 shillings fine or imprisonment.

The strictness of the plan was set from the top by Bevin, and he was adamant that only through a ballot and very limited exemptions (such as flying duties in the RAF and Fleet Air Arm) would the selection be fair. The War Cabinet agreed, stating that the scheme would only be accepted by the public if it was confident of impartiality (CAB 65/36/30).

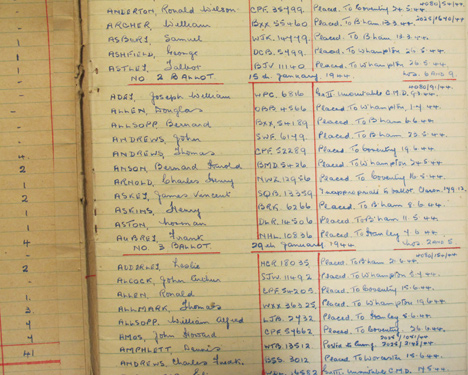

Amongst our holdings from the Ministry of Labour and National Service (LAB) here are several records relating to the Bevin Boys. Perhaps most interesting is LAB 45/93, which is essentially the register of coal mining ballotees. A glance through the file shows us names, regimental numbers, and dates of selection for each ballotee. The locations that ballotees were sent to shows how geographically spread the scheme was, and although initially the aim was to assign participants to training centres and mines as close to their homes as possible, this became increasingly difficult.

Detail from LAB 45/93

The 1983 radio programme ends with some contributors explaining how they received no answers regarding release schemes after victory was secured, even though officially the date of demobilisation was meant to be the same as for those in military service. Some complained that after they had been placed with armed services their efforts in the mines had not been counted towards their service and that many military personnel were not aware of the scheme.

Indeed, this lack of recognition is something that the surviving Bevin Boys are probably all too familiar with. The establishment of the Bevin Boys Association in 1989 at least allowed for ballotees to share their experiences and memories, and provide support for each other, but the unveiling of the memorial at Alrewas earlier this month finally represented official recognition of their efforts and sacrifices.

The piece in ‘The World at War’ is also good as it shows how even if you came from a privileged background you could also be called up and ‘class’ was not a barrier or reason not to be a ‘Bevin Boy’.

Thanks David – you are quite right, the decision to ensure the ballot was as wide as possible meant that people from very different backgrounds worked side-by-side in the mines.

As for the World at War – I have already begun lobbying friends and family for the box set for my next birthday…

Simon,

Thanks. The World at War (also doing the rounds on one of the historical channels)is still very useful for historical research although a number of files have been released since then, I recommend the episode ‘Occupation’ on The Netherlands until 1944, it is particularly relevant to the attempts to save the Jews in The Netherlands.

David

If anyone is interested in a first hand account of life as a Bevin Boy a recently published book “War Underground” by Michael Edmonds is a must. Michael served as a miner in the South Wales Coalfield. His graphic account of life as a Bevin Boy in this mining community both above and below ground will be of interest to anyone wanting an insiders knowledge of this subject.

Thank you Derek – sounds like a fascinating read.

i was a bevin boy and worked in appaling conditions at teh coal face with wooden beams holdingthe roof y up and which sometimes collappsed

Yes I would be. My dad was aNevin boy in the war. He found it very hard as a young lad from a public school. He was also very tall and it was back breaking work. He went to a mine in Nottinghamshire.

How can I find his records. ?

Hi Mary,

Thanks for your comment.

Sorry, we can’t answer research requests on the blog, but if you go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts by email, live chat or phone.

Best regards,

Liz.

Your blog came up as a loooong list of single words down the left of the site!Pity. My uncle was a Bevin boy!I may add that I have been totally unable to access anything from the latest newsletter. some technical problem?

Hi Christine, please can you tell us what browser you’re using? You may want to try clearing your cache (hold down Ctrl + F5) on your keyboard. If problems persist, please can you email webmaster@nationalarchives.gov.uk so we can investigate futher.

Many thanks,

Ruth

My dad John James was a bevin boy unfortunately he died 3 weeks ago aged 86 he never talked about what he went through down pit mum said he was embarrassed at been a bevin boy .l Don,t understand why he was embarrassed her should have been proud to face what he did at18years of age along way from home living with family’s who resented him been there .I found out that he was in the Durham pits he might not have been proud at what he did but I,am proud of him .

It certainly seems that no Bevin Boy should have been embarrassed about their service. They made enormous sacrifices and without there efforts it is fair to say that the raw materials required to support the war effort simply would not have been transported quickly enough.

Simon

Ahem, *their.

We think my grandad david leslie from east weymess kirckaldy fife scotland was a Bevin boy he had alot to do with the wiring for explosives .How can I find out for sure that he was actually a bevin boy ? He died when my mum was 14 and she is 68 now please help I am very interested in this lv p xxx

I am trying to trace any information about my father Ernest Sharpe who trained at the Askern pit then went on to work at Mexborough.

Any information would be appreciated.

My dad was released from the RAF to work in the mines. How can I find out more.

Hi Graham,

Unfortunately we’re unable to help with family history requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

I hope that helps.

Nell

I have been making enquiries on behalf of my brother Jack, now 90 years old. He served as a Bevin Boy at Langley Park, Co Durham, I went down the mine with my mother and father to see him at work driving the haulage engine. He was called up from being a student at the Royal Academy of Music, but does not now recall where he trained. His neice and I are trying to get him a veteran’s badge and would like to hear fromanyone who trained or worked with him/

I’m 90 in a few days and can certainly remember where I trained. ( usually!) Contact the Bevin Boys secretary Liz Todd [contact details removed by admin according to moderation policy http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/moderation-policy/; find contact information here http://www.bevinboysassociation.co.uk/ ]

I’m sure she’ll help with any queries you might have.

Searching for any records of Eric Victor Davis Bevin Boy believed Wales

Hi Nicola,

Unfortunately we’re unable to help with research requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

I hope that helps.

Nell

Would love to hear from anyone who lived at the Cowdenbeath Hostel as Bevin Boys.

I worked at the Nellie Pit Lochgelly.1944-45.

I am the official archivist for the Bevin Boys Association -Details of our organisation can be found at http://www.bevinboysassociation.co.uk. Whilst unfortunately most of the official Bevin Boys records were destroyed after the war we do still have a newsletter that goes out to our members regularly. Appeals for information regarding individuals such as the posts on this website are often included and a good way to contact remaining Bevin Boys. We do also have a yearly reunion, the most recent being in September 2016 in Blackheath London.

Hi Barbara,

Thank you so much for sharing this information. I am sure it will be of great interest to anyone looking to research more about individual Bevin Boys and wider information about their work.

Thanks,

Simon

My dad and uncle were welders but conscripted from Lanarkshire to the Durham/Northumberland area. My dad was assigned to Bedlington where he worked in the Dr Pit and played for the pit team beating Blyth Spartans in an F.A. cup game (he giving an assist and scoring in a 2 – 1 victory). He was seriously injured when he was run over by a bogie, ending his football career. He made many friends in the area and loved where he was billeted in Ponteland ( I think) or Newcastle. Like so many of other contributors I would like to get his wartime records. Given the links I will now be doing so.

My father was a Bevin Boy at Ogilvie Colliery in Deri, South Wales, but he also told us he was a sub mariner as well, on HMS Tantalus, could this be possible? Were Bevin Boys taken from the forces, as well as from civvy street? I have tried to find information about him at this colliery, but to no avail.

Ron

My Great uncle (Grandfathers brother) was a Bevin boy for. 2 years but died as a US Soldier in Germany.

No idea where he was as a Bevin boy but as a dual passport holder he moved back to the USA to join up. He joined the US Army and was sent to Europe where he arrived some time around VE Day. Lucky him you’d think. Sadly in June 1946 in a train Platform in Germany, he died as a result of a US Military Policeman accidentally firing his rifle striking Poor William Dix in the head, killing him.

So in answer to your question I wonder if your Father may have been a Bevin boy first then transferred to the Navy. He obviously enjoyed being below Ground or Sea. A brave man.