1From Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent to Princess Alice of Greece, princess nurses have gifted their talents to hospitals and medicine, particularly during wartime. However, missing from this history of royal altruism are the African princesses – notably Princess Omo-Oba Adenrele Ademola, the daughter of the Alake of Abeokuta, a significant king in the southern region of Nigeria, who after attending school in Somerset in 1936, began a life and career in British nursing that spanned over 30 years. Some of this was captured in the lost film produced by the Colonial Film Unit, ‘Nurse Ademola’.

First arriving in Britain aged 22 in Plymouth on 29 June 1935, she resided at the Africa Hostel in Camden Town, established by the West African Students’ Union (WASU), a significant social and political organisation for West Africans in Britain. This space acted as a haven for Ademola, as it did for many other African students and visitors during the early 20th century. It is here that she attended social events and committees, and the Africa Hostel is noted as her residence address until she returned to Lagos temporarily in 1936 2.

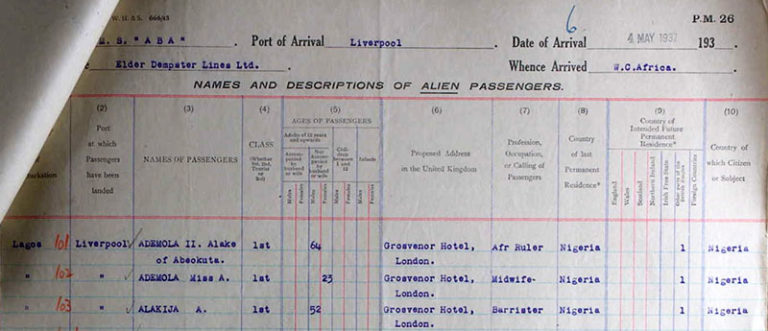

During her early career in Britain, Ademola balanced her role as a princess with the demands of her vocation as a nurse. As a princess, she returned to England in 1937 with her father and brother, Prince Ademola III (the future Chief Justice for the Federation of Nigeria) for the coronation of King George, staying at the Grosvenor Hotel, London 3. While it’s unclear whether Princess Ademola attended the coronation of George VI on 12 May 1937, she attended many royal social events from May to July 1937, including royal garden parties at Buckingham Palace and a royal gathering hosted by her father at the Mayfair Hotel, in May 1937. She also conducted royal visits to the Mayor and Mayoress of London at Mansion House and notably the Carreras cigarette factory in June 1937 4. It is likely that she continued to attend royal appointments until her father’s departure to Paris in early July 1937.

Still, the film ‘Nurse Ademola’ centralises her role as a nurse. The Colonial Film Unit was a division of the British Ministry of Information that, between 1939-1955, produced 200 propaganda films on the African continent, promoting colonial development and generating support for the imperial war effort.

‘Nurse Ademola’ played an important part in this as a uniquely feminine perspective. Produced in 1944-45, ‘depicting an African nurse at various phases of training at one of the great London hospitals’, it was said to have inspired many African viewers at its screenings across West Africa 5.

Objectively, ‘Nurse Ademola’ testifies to the significance of Ademola’s contribution to the national efforts as a nurse; a glowing role model for the empire. It can also be assumed that the film examines the distinctive role and experiences of Ademola’s life and service in Britain. But this is only an assumption as the location of the ‘Nurse Ademola’ film is unknown. Its absence is symbolic of wider historical absence of African women, even those of royal status.

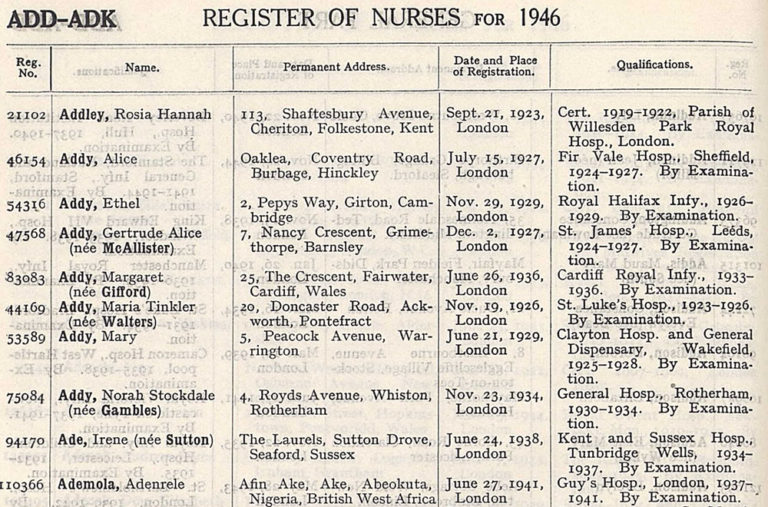

Outside of her film, Ademola’s life in Britain can be broadly trailed through her health work. When she arrived with her father in 1937, she is recorded as a ‘midwife’, which epitomises her presence in the historical records after this. In 1939 she is listed as a part of the nursing staff at St Saviour’s ward at Guy’s Hospital, and by 27 June 1941 she becomes a registered nurse at Guy’s hospital, having passed her nursing examinations after six years of training.

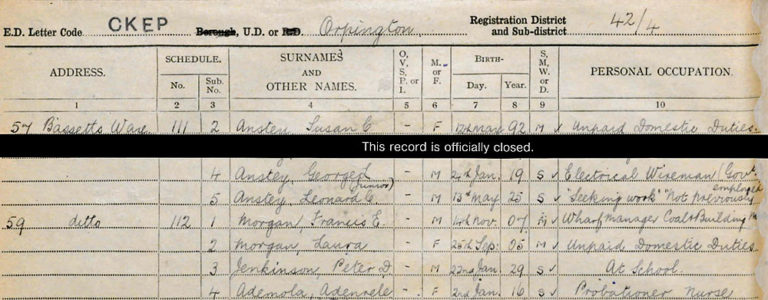

From 1941, she moves between hospitals; recorded at Queen Charlotte’s Maternity Hospital in London before being listed at New End Hospital in Hampstead in December 1942, having passed her Central Midwives Board exam 6.

At this stage, her last definitive sighting in the archives was in September 1948, before her father’s departure from Nigeria and abdication of the throne. She returned from Lagos with a man believed to be her husband, Timothy Odutola, a 46-year-old trader. Here she again lists herself as a nurse, residing in Limpsfield, Surrey before moving, accompanied by her husband, to Balmoral Hostel in Queensgate Gardens, South Kensington in 1949 7.

Without the film, Ademola’s experiences in London as a black woman and as a nurse are lost. Moreover, her life can only be reconstructed through the arduous struggle of researching in the historical archives. First, our view of Ademola’s personal experiences across various hospitals is hindered by GDPR restrictions, which limits access to hospital records within a 100-year period. More adversely, her visibility in the archives is significantly hindered by haphazard recordings of personal details, i.e. names, birth dates etc.

Throughout this research, five variations of her name have been encountered, even on official records, confusing her presence in the archives, possibly even with others who shared her surname. Such challenges are rife when examining black populations and represent a larger issue: the failure to consider black people/black histories a priority. Contemporarily, the lives of black people were considered ‘second-class’ and therefore detail and accuracy in records were deemed unnecessary.

Still, The National Archives, alongside historians of black history and community groups such as the Young Historians Project, are beginning crucial initiatives to recognise the histories of black people in the archives. But there is still so far to go.

African nurses such as Princess Ademola, through their migration, settlement and contribution to British society, hold equal claim to the attentions of historical archives as any Florence Nightingale or Edith Cavell. They must be also be recognised for their struggles against social and racial adversity. It is our responsibility to bring forth histories like Princess Ademola’s and transition the narrative of black women in Britain from the abstract to the celebrated.

This research is part of a larger investigation into African women and the British Health Service from 1930-2000, led by the Young Historians Project (YHP).

The following research guides, produced by The National Archives, might be of further use for research into the immeasurable contributions of nurses from overseas, and Black British history more generally: Black British Social and Political History in the Twentieth Century, Doctors and Nurses, Immigration and Immigrants, and Passenger Lists.

Notes:

- The title of this article is quoted from a newspaper article announcing that Princess Ademola had become a nurse at Guy’s Hospital; “News in Brief.” Times, 4 Jan. 1938, p. 15. The Times Digital Archive ↩

- First Arrival, ‘A Ademola’ (1935) ‘Incoming Passengers’ 25 June 1935 UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960. Her time at the WASU Africa Hostel noted by Marc Matera in Black London: The Imperial Metropolis and Decolonization in the Twentieth Century, USA: University of California Press, 2015. Her return to Lagos; ‘A. Ademola’ (1936) ‘Departure to Lagos’ 9 September 1936, UK and Ireland, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960 ↩

- Ademola’s landing in Britain noted ‘Miss A Ademola’ (1937) ‘Incoming Passengers, Liverpool’ UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960. Arrival with her father for the coronation noted in ‘Picture Gallery’. Daily Mail, 5 May 1937, p. 11. Daily Mail Historical Archive, 1896-2004 ↩

- Evidence of their royal appointments across London during the coronation; ‘Court Circular’. Times, 26 June 1937, p. 17. The Times Digital Archive ↩

- References to Nurse Ademola screenings in Colonial Cinema, March 1945 Vol III no.1 (Colonial Film Unit; Ministry of Information) p13 ↩

- 110366 Ademola, Adenrele’ June 27 1941, London’ Register of Nurses for 1946 p22; ‘303 Rw Ow Ademola Adenrela’ St Saviours Ward, North Polling District B, London, England, Electoral Registers, 1832-1965 p31; ‘Ademola, Adenrele’ 109811, 16 December 1942, ‘Roll of Practicing Midwives 1943-44’ p5 ↩

- ‘Adenrele Odutola nee Ademola’ 27 September 1948, Incoming Passenger List UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960; Polling District U – Queen’s Gate Ward (1949), London Electoral Register 1832-1965 p48 ↩

My work on Nurse Ademola has been overlooked in this blog. I included her in my books Mother Country – Britain’s Black Community on the Home Front 1939-45 (The History Press, 2010) & War to Windrush – Black Women in Britain 1939-48 (Jacaranda Books, 2018). I have also uncovered a rare photo of her & will include this in my next book Under Fire – Black Britain 1939-45 (The History Press) out on 3 August 2020. I have also featured Nurse Ademola in my talk ‘Black Nurses in Britain Before the NHS’ most recently at the Royal College of Nursing (March 2020).

Thank you Montaz Marché, for such an informative, and well-written blog about the little-known life of Nurse Ademola and her immense contributions to nursing, which is particularly timely as well, during the present pandemic. In response to the previous comment, it might be worth noting that National Archives blogs are restricted to around 1,000 words, which means that authors are limited on what they can and can’t include. That said, this is a fine piece of research from a hugely talented young scholar, and one that I certainly look forward to hearing more from. Thank you, Ms Marché.

Great piece. Thanks for doing this research and highlighting Princess Ademola and what is known of her story. Do we know if she had any children?

Dear Montaz Marche,

A superb piece of research, enabling us to glory, in the continuing support the AFRICAN WOMAN, has always given us; but mostly seems to be invisible, most of the time; not only to us the European, but also with scant regard from her own nationals as well. You mention Edith Cavell, which is a good choice. But I would like to point out, shout her name loud, from here to the Caribbean; MARY SEACOLE, MARY SEACOLE, MARY SEACOLE. The Jamaican nurse who at her own accord, after the British War Office had refused her help, made her own way to Crimea, with her British Hotel, to help all the injured soldiers, with her nursing abilities; which on her return to England, nearly left her destitute. I love delving into the African history, which is part of ours as well. We should be proud to stand beside you, to help you with this deliverance from the debasing + defilement, from the European, that shows no-one any respect. Once again thank you, for your time and energy. Paul Tuley.

I’m coming to this over 2 years on…

Congrats Montaz on a fascinating piece.

And Stephen, regarding ‘Black Nurses in Britain Before the NHS’, are you aware of Dzagbele Matilda Asante – I Was Nursing In The UK Before Windrush And The NHS?

https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/article/section/bhm-firsts/dzagbele-matilda-asante-i-was-nursing-in-the-uk-before-windrush-and-the-nhs/