This blog article is part of the 20speople season – a season of exhibitions, activities and events from The National Archives that explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s.

In 1918 the book ‘Married Love: A New Contribution to the Solution of Sex Difficulties’ by Marie Stopes (1880-1958) was published. Aimed at married couples, it became an instant bestseller and went through a number of editions throughout the 1920s.

The book was controversial, causing a ripple through polite society with its advice on sex and intimacy in marriage. In the book Stopes reflected on the education of girls, which ‘so largely consists in the concealment of the essential facts of life from them’ (see footnote 1). She went on to describe the importance of good sexual relations between a husband and wife, including the taboo subject of female pleasure, noting that ‘the mutual orgasm is extremely important’ (footnote 2).

The topic of family planning was also broached, with Stopes writing on the ‘wise precaution of delay’. She cautioned married couples to delay conceiving a child immediately after marriage ‘to secure the lasting happiness of the married lovers’ (footnote 3), and further advised that a minimum of two years should pass before the birth of a second child (footnote 4). At the start of the decade the child mortality rate, for children under the age of five, was c. 141 deaths per thousand births: dropping to 101 deaths per thousand births by 1930 (footnote 5). Stopes lamented ‘what a hideous orgy of agony for the mothers to produce in anguish death-doomed, suffering infants’ (footnote 6).

Stopes’s campaign for sex education rested, in part, on the theory of eugenics – a now discredited scientific theory formed from the idea that the human race could progress based on ideas of heredity. Broadly, supporters of eugenics believed that people could inherit mental illness, criminal tendencies and a predisposition to poverty. The book ‘Married Love’, while having eugenic undertones, was not explicitly eugenic. Stopes wrote ‘of the innumerable problems which touch upon the qualities transmitted to the children by their parents, the study of which may be covered by the general term Eugenics, I shall here say nothing…’ (footnote 7). Eugenic ideas were, however, played out throughout the book. Stopes was concerned that there were sections of society who ‘encourage the production of babies in rapid succession which are weakened by their proximity’, exclaiming that ‘each child, following so rapidly on its predecessor, saps and divides the vital strength which is available for the making of the offspring. This generally lowers the vitality of each succeeding child, and surely even if slowly, may murder the woman who bears them’ (footnote 8).

Despite the book being famous for its advocacy of birth control, specific methods of contraception were not referred to in any depth (Stopes reasoned that the pulling out method or coitus interruptus was not ideal as it left the woman unsatisfied (footnote 9). Differing options for birth control were covered in her 1919 book ‘Wise Parenthood’, “the ‘practical sequel to ‘Married Love’”. Other topics covered in ‘Married Love’ included women’s position in society, the importance of menstrual cycle timings (in a time before ovulation was understood), infertility and even a futuristic take on artificial insemination. She wrote that ‘some high-minded women have been endeavouring for some time to found an Institute for the scientific insemination of women war-deprived of mates, so that though husbandless they may have the joy and sacrifice of child-bearing under properly protected conditions’ (footnote 10).

Stopes was a visionary in many ways. During the 1920s, Stopes pioneered ways to discuss family planning and provide birth control to the general population. Stopes attempted to disseminate her ideas to captive theatre audiences by writing a play entitled ‘Married Love’ (under the pseudonym George Dalton). Its theme was the impotence of a husband and the ignorance of a wife about how to conceive a child. The play failed to obtain a license to be performed at the Royal Court Theatre in November 1923, with the Lord Chamberlain, George S Street, stating ‘no excuse is sufficient for inflicting such an unnecessarily disgusting play on the public’ (footnote 11).

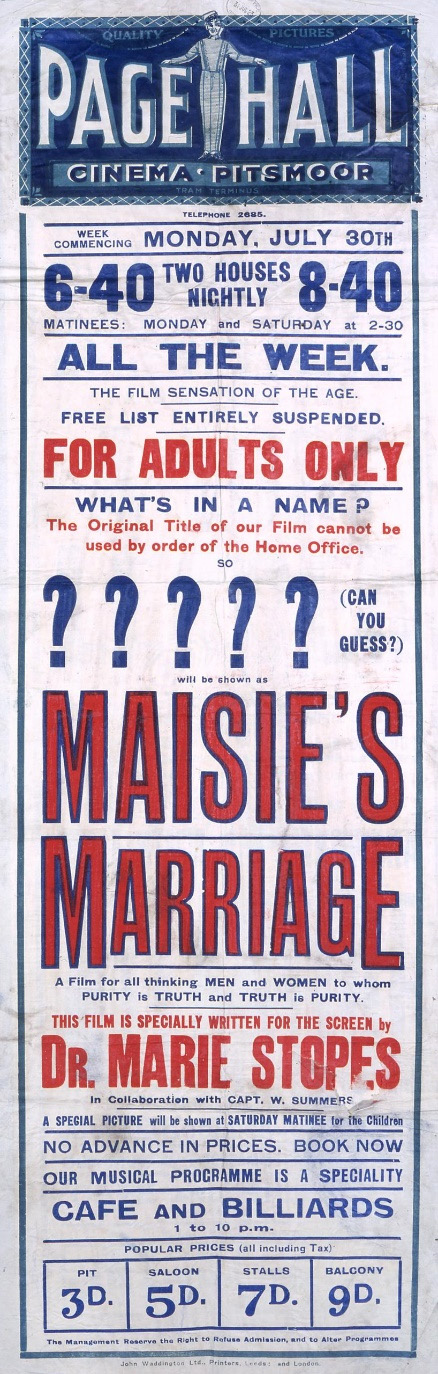

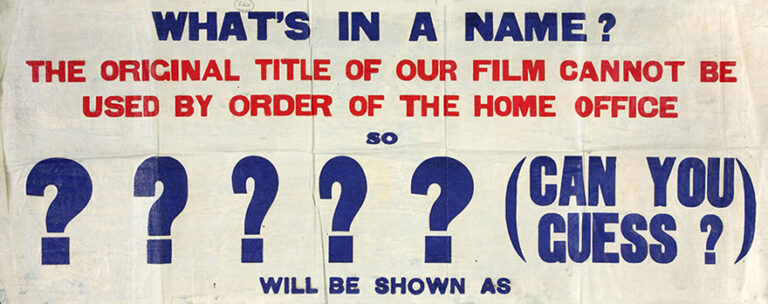

That same year Stopes wrote a screenplay based on themes of the book, a cautionary tale about the importance of having fewer children in order to avoid a life of destitution and unhappiness. Its original title ‘Married Love’, however, was deemed impermissible by the Board of Censors due to the perceived distasteful contents of the book. In contrast to the play, the film was eventually given a license after the publishers of the film approached the Board of Film Censors ‘offering to eliminate all incidents from the film dealing with the question of birth control and to make no mention in the posters or other printed matter that the film was founded on Dr. Marie Stopes’s book “Married Love”’ (footnote 12).

Despite this, the Page Hall Cinema in Sheffield decided to allude to the original name of the film in its promotional material. After an outraged Police Constable wrote into the Home Office complaining about the posters, the Home Office responded that the promotional material was ‘a breach of the spirit of the undertaking given to the Board and is a rather discreditable trick for attracting the public’, advising the Sheffield authorities to give the licensees a sharp warning (footnote 13).

Today, Stopes is also known for establishing the UK’s first birth control clinic in London in 1921, which had a significant social impact on maternity and child welfare and led to the growth of national clinics. The clinics provided birth control advice and various barrier-type contraception devices, such as the cervical cap.

Birth control was seen as immoral by many in 1920s society but Stopes reasoned ‘Even when a child is allowed to grow in its mother, all these millions of sperms are inevitably and naturally destroyed every time the man has an emission, and to add one more to these millions sacrificed by nature is surely no crime!’ (footnote 14).

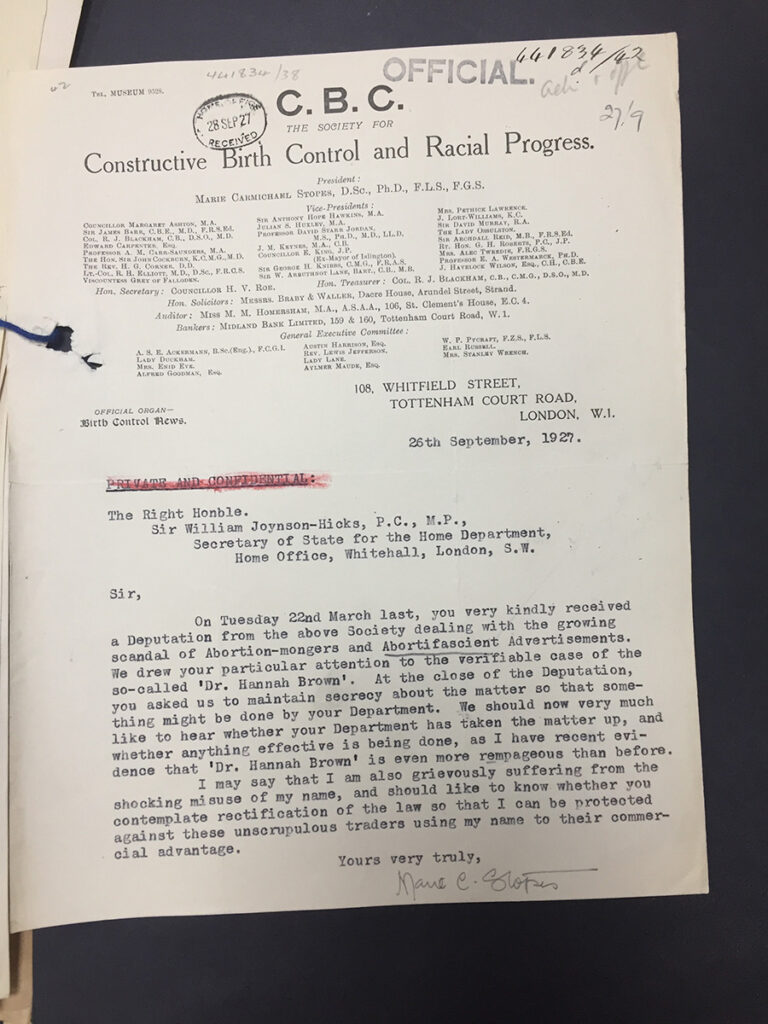

Stopes saw her preventative birth control methods as ‘wholesome’ options for women, as opposed to taking potentially dangerous or ineffective abortifacients (footnote 15). In fact, Stopes tried to distance herself from illegal abortion. The National Archives holds a letter from Stopes showing concern over the ‘growing scandal of Abortion-mongers and Abortifacient Advertisements’, complaining that her reputation was being damaged by the use of her name in advertisements by unscrupulous traders (footnote 16).

In the letter, Stopes is writing from her position as President of The Society for Constructive Birth Control and Racial Progress (CBC) – a eugenics society Stopes co-founded in the early 1920s. It was the CBC that was used to administer Stopes’s birth control clinics, and it’s this association with eugenics that has led to Stopes’s controversial legacy today (footnote 17).

In the early 20th century eugenics was more mainstream than it is today, with people from all walks of life, including the aristocracy, the clergy, socialists, conservatives and an array of leading intellectuals supporting its principles. Differing schools of thought had divergent opinions on how eugenics should be applied practically to improve society. Some, such as the Eugenics Society (of which Stopes was a member), advocated for the sterilisation of those deemed ‘unfit’. In the next blog I will take a look at some of the records in The National Archives’ collection that can tell us more about eugenics in the 1920s.

Further reading recommendations

L A Hall, Sex, Gender and Social Change in Britain since 1880 (London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). Available in the library, shelf mark 305.3 HAL.

L A Hall, Situating Stopes: or, putting Marie in her proper place.

L A Hall, Women’s rights to sexual pleasure, (August 2019).

R Hall, Marie Stopes: a biography (London, Andre Deutsch, 1977). Available in the library, shelf mark 920 STO.

M C Stopes, Married Love: A New Contribution to the Solution of Sex Difficulties (London, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, Ltd). First published in 1918. Various editions are available on archive.org.

M C Stopes, Wise Parenthood: A Practical Sequel to Married Love (London, G.P. Putnam’s Sons Ltd). First published in 1919. Various editions are available on archive.org.

J Weeks, Sex, Politics and Society: The Regulation of Sexuality Since 1800 (Essex, Longman Group Limited, 1981). Available in the library, shelf mark 306.7 WEE.

Marie Stopes’s personal and scientific papers can be found across a range of institutions, including the Wellcome Collection and the British Library.

You can watch Maisie’s Marriage on the BFI player (£).

Footnotes

- M C Stopes, ‘Married Love: A New Contribution to the Solution of Sex Difficulties’ (London, G P Putnam’s Sons, Ltd, Seventh Edition, 1920), 60.

- Stopes, ‘Married Love’, 94.

- Stopes, ‘Married Love’, 132.

- Stopes, ‘Married Love’, 140.

- A O’Neill, ‘Child mortality in the United Kingdom 1800-2020’ (2019, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1041714/united-kingdom-all-time-child-mortality-rate/)

- Stopes, ‘Married Love’, 155.

- Stopes, ‘Married Love’, 143.

- Stopes, ‘Married Love’, 153-154.

- Stopes, ‘Married Love’, 96.

- Stopes, ‘Married Love’, 150.

- Memorandum by George S Street, Ceremonial Department, St. James’s Palace, 9 October 1923.

- Memorandum by S W Harris, Secretary to the Home Secretary, ‘Censorship Cinematograph Films’, 30 June 1923.

- HO 45/11382, Letter from the Home Office to the Chief Constable of Sheffield City police, 3 August 1923.

- Stopes, ‘Married Love’, 156.

- Stopes, ‘Married Love’, 155-156.

- HO 45/24782, Letter from Marie Stopes to Sir William Joynson-Hicks, Secretary of State for the Home Department, 26 September 1927.

- The BBC, ‘Abortion provider changes name over Marie Stopes eugenics link’, 17 November 2020.

Eugenics were later to be linked to the Nazis and Eugenics were hideous and cannot be condoned in any form.

It seems now that Eugenics is a valid idea. We now know how much of a role that genes play in how a person develops both physically and mentally. These people were certainly onto something even though they did not have any idea of the mechanism involved.

The chapter on Stopes’s venture into filmmaking in my doctoral thesis is greatly indebted to Home Office papers in the National Archives.