Content note: This blog post references homophobic attitudes and the historic policing of LGBTQ+ lives. The term queer is used, as it is the most-used word in The National Archives’ records for men to self-describe their sexuality during this period.

On a December evening in 1932, two police officers entered a large Victorian townhouse. They were greeted with a kiss on the hand from a flamboyant figure, believed to be male, wearing exaggerated makeup and an evening dress; this individual went by the name Lady Austin (see footnote 1).

Welcoming them in, Austin remarked ‘Don’t go and get too fruity yet’.

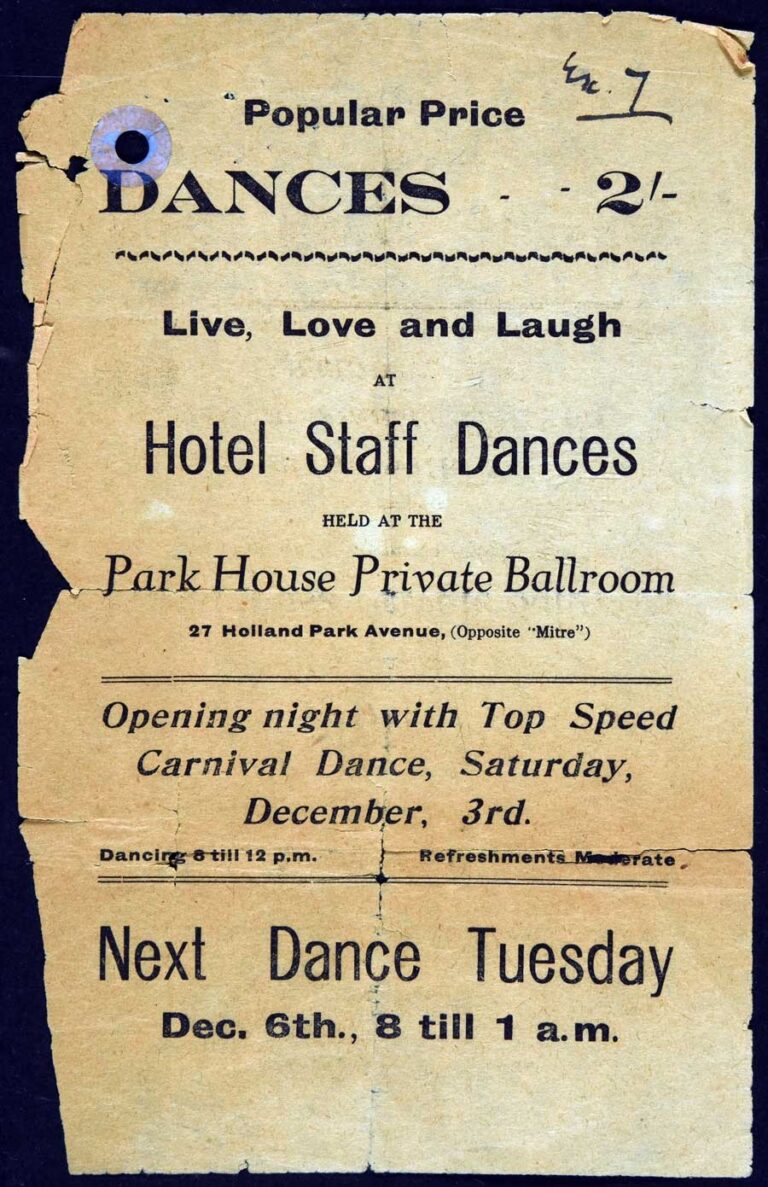

The police officers were undercover. The venue was the Park House Private Ballroom, Holland Park, London (see footnote 2).

Ballroom gatherings

In the early 1930s, this ballroom at 27 Holland Park Avenue was frequently rented out for dances by the ostentatious Austin for gatherings of ‘Lady Austin’s camp boys’. Such queer parties provided spaces for individuals to experiment with sexuality and gender expression in ways that were not widely socially accepted. These ballroom gatherings were known as drag dances, where fancy dress costumes and transgressive clothing that questioned defined gender roles were encouraged.

While some of London’s clubs of the era actively engaged a queer clientele, other spaces, such as Park House, were only occasionally rented to members of this underground community. This was a profitable commercial model, which was increasingly adopted in this era. It was also less risky than creating a permanent space, in terms of visibility and policing. These queer spaces spread out from the West End via Hyde Park (a prominent cruising spot) across to outer West London. There were certain distinct trends and even professions that engaged in these West London spaces (see footnote 3).

‘Are you going to the “Drag” tonight?’

On 13 December 1932, two undercover police officers, PC Labbett and PC Chopping, were sent to investigate the premises at Holland Park Avenue. They entered the nearby Mitre Public House, following an individual with rouged lips, pencilled eyebrows and scented clothes who asked, ‘Are you going to the “Drag” tonight?’ The plain-clothed officers then joined their new acquaintance across the road at the Park House Ballroom and paid a small fee on the door. They were introduced as ‘two camp boys and friends of mine’. They were greeted by Lady Austin’s kiss on the hand. Austin acted as barman and MC at the event.

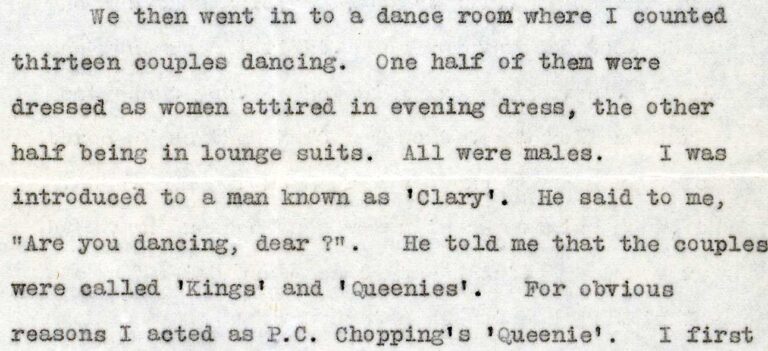

On this occasion, the ballroom contained around 60 people. Police observed:

‘One half of them were attired in evening dresses, the other half being dressed in lounge suits. All were male.’

(See footnote 4)

The set-up was explained to the undercover officers; those wearing dresses were termed ‘Queenies’ and those in lounge suits called ‘Kings’. The officers each adopted a role and, in keeping with their disguise, acted as a couple. PC Labbett stated, ‘For obvious reasons I acted as PC Chopping’s “Queenie”‘, illustrating the lengths police officers went to while investigating queer spaces. Such methods were controversial even at the time and could be seen as entrapment (see footnote 5).

Both officers socialised and danced with other attendees. One individual known as Clary explained ‘there were only five real women present and they were all Lesbians.’ PC Chopping asked if everything was safe, and was told:

‘Safe dear, of course they can’t touch us. If the “Bogies” or “Dicks” come, give a wrong name and address, I always do.’

(See footnote 6)

Despite the police persecution of these spaces, it appears that they offered a sense of freedom and safety to their patrons. Avoiding investigation was part of the queer way of life, and individuals developed techniques to try to evade police scrutiny. These records show an accepted language for queer spaces, which the police engaged with. When PC Labbett was asked if he had traded tonight yet he replied, ‘Twice with my boy friend’ and pointed to PC Chopping.

The officers watched couples sneak off to the toilets or gardens, and when the dance ended at 01:00, attendees were seen to pair off and leave the property together.

Working class queer culture

Not long afterwards, on 20 December, a waiter called William who worked and lived at the Balmoral Hotel was handed a flyer by a female friend, a chambermaid called Nancy. The handbill advertised a ball for hotel staff at Park House. The flyer summed-up the drag dance with the compelling phrase ‘Live, love and laugh’. Joyous, coded language was common in the advertising of such events.

Hospitality professionals in the hotel and waitering trades seemed to be closely linked to queer networks at this time, being a safe space to advertise. The professions of ball attendees were noted; porters, waiters, and valets were common. This handbill was one of 500 circulars shared to promote the event. It was to be used as evidence in court.

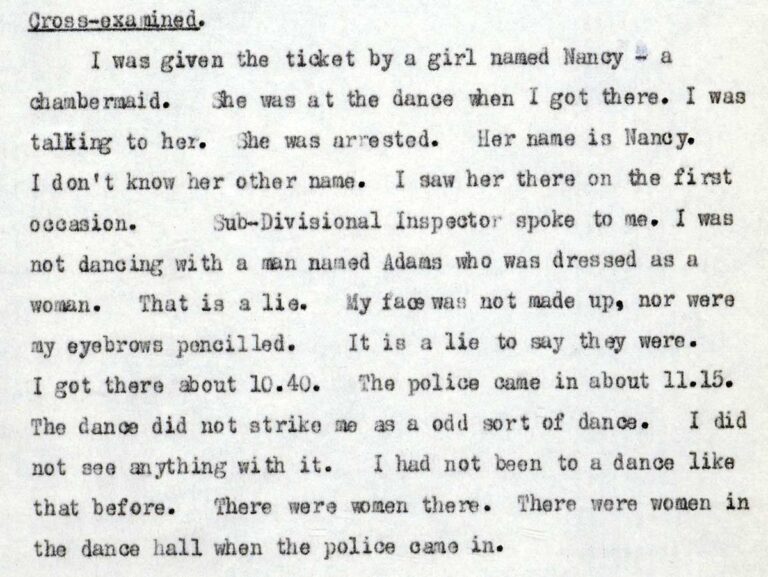

Having received the flyer earlier in the day, William arrived at the ballroom at 22:30. He would have been greeted by two men in the front garden, kissing with their arms around each other. Police statements note William as wearing make-up and having dyed hair, claims that he later denied. He said he had never visited the venue before.

At the venue undercover officers again spoke to the patrons. An individual called James asked:

‘When did you discover that you were like it. I did two years ago. Other people would sympathise with us if they knew and knew we couldn’t help it.’

As these lines show police observations of queer spaces often reveal unexpected personal reflections on identity and sexuality.

The ballroom was again divided into Kings and Queenies. Lady Austin explained, ‘We take it in turns; I was a Queenie last week.’ These subversive spaces show a playful attitude to drag, gender identity and masculinity, which is distinct from our current concepts of gender.

The raid – ‘love not profit’

At 23:25 Chief Inspector Smith and other officers entered the ballroom. He reported:

‘I waited till all the officers had got round the room. Then I announced we were police officers. I had the band stopped. I then shouted out, “I want Lady Austin and Betty”.’

Prisoner Salmon said, ‘I am her ladyship. Betty is not here.’

As the premises were raided Lady Austin defended the dance, and when the police warrant was read out, said, ‘Surely only members of our cult are here. What harm are we doing? You don’t understand our love.’ Police enquired what Austin meant by ‘members of our cult’ and were told, ‘Why Lady Austin’s camp boys of course.’ Austin claimed they knew each other from Betty’s at Baker Street, a similar type of establishment, showing the wider network of queer clubs in the metropolis.

Austin explained the venue was run for love not profit:

‘How difficult is it? You don’t understand. We don’t like women, a drag is a dance without women and give and take is between ourselves. Oh, dear, this trouble would be obviated if they made our love legal.’

Lady Austin

It would take a further thirty years for homosexual acts in private to be decriminalised in England and Wales.

Evidence

During the raid, police collected witness statements, reports and photographs. Objects were also gathered as evidence from the ‘crime’ scene. In the ballroom police found powder puffs, lipsticks, ladies’ knickers and shoes (see footnote 7). Uniquely, this includes a red lounge suit (pictured) worn by one of the ‘Kings’, which is still in existence in our collection. In evidence this is described as a ‘red costume’; the deep maroon colour is striking, the trousers flared, the sleeves ballooned. The overall effect is decadent and bohemian.

The records suggest this was worn by an individual called John, a 22-year-old waiter, who was later identified in the court proceedings as the partner of Austin and one of the people who orchestrated these balls (see footnote 8). Historian Matt Houlbrook notes this item was actually produced for the defence, and used as evidence that John was not wearing a drag-style outfit. The defence argued that the costume was fancy dress, and not improper.

Ultimately, 50 men and six women were arrested. The police carefully noted the names of ‘all men dressed as women’.

In court

The courtroom was packed, with one newspaper remarking that ‘numbers’ were used around the necks of those on trial to distinguish them from everyone else in court. At the trial the use of the word ‘camp’ was questioned. The individuals in the dock were asked what they believed it meant. They were also asked whether they witnessed any indecency, which was mainly denied. Some family members gave evidence to testify to their relative’s character. Even before the trial verdict many had lost their jobs.

The principal three figures in the dock were Austin, John and Kathleen, the housekeeper. Austin and John admitted running the dances together, while Kathleen rented out the space to them. She defended the gatherings, asking ‘what harm does it do?’

Despite testimonies to this effect, at the trial Lady Austin was one of the foremost individuals to be found guilty, with the principal charges of ‘conspiracy to corrupt morals’ and ‘keeping a disorderly house’. 28 individuals received sentences, mostly charged with aiding and abetting. Between them, all the sentences added up to nearly 25 years. Lady Austin was given a 15-month prison sentence, while John received 20 months in jail. This was not a lone case – but part of a series of raids designed to ‘smoke out’ such subversive, accepting spaces.

Life after the dance

It is not easy to trace the fascinating individuals involved in this case beyond this moment in time, due to the limited information about them. However, we can see that a number of them remained working in the hotel trade through the 1939 Register. Hopefully they were not deterred by their involvement in this case and continued to use their networks to spread queer joy.

Footnotes

- This name had been adopted by Austin after an event they attended at the Royal Albert Hall the previous year. It is possible that the event in question was Lady Malcolm’s Servants Ball or the Chelsea Arts Ball – both of which were marked by the wearing of gender transgressive clothing. Serious Charges Against Dancers | West London Observer | Friday 24 February 1933 | British Newspaper Archive.

- This blog post is predominantly based on records CRIM 1/638 – CRIM 1/640. Quotes used are mainly from CRIM 1/639.

- Many thanks to Matt Houlbrook for sharing his research into this West London phenomenon.

- This quote is from the police report. We do not know how these individuals would have identified in their own words, in terms of gender or sexuality.

- Some detail around this from the 1960s is recorded in HO 291/1060.

- The use of false names and aliases was understandably important to many of these individuals. For current researchers it can make it harder to trace these people beyond the singular moments captured in criminal records.

- None of the photographs, and most of the objects, do not survive.

- Serious Charges Against Dancers | West London Observer | Friday 24 February 1933 | British Newspaper Archive.

My uncle was gay, as he would have referred to himself. He was born in 1901 and he lived in North West England. Thanks for the insight into how his life may have been, how he had to hide any enjoyment and how he would have been judged.

How times have changed….and what harm did it do as these people were all Adults…When I was young , my uncle Norm who was a prisoner of War in Changi Goal once told me about the shows put on by other prisoners , some of who dressed as women….his comment was that many who crossed dressed for the shows liked it so much they Identified as women. This article gives an insight to Victorian life

and the strict moral era of that time….

Thank you so much. What a wonderful resource The National Archives are.

Please keep up the good work to educate, inform and dare I say it ‘entertain’.

We are very fortunate.

Thank you.

I felt very sad after reading this blog and wondered how all these individuals who were sentenced coped in prison, and whether they were stigmatised and bullied. We should find out really.