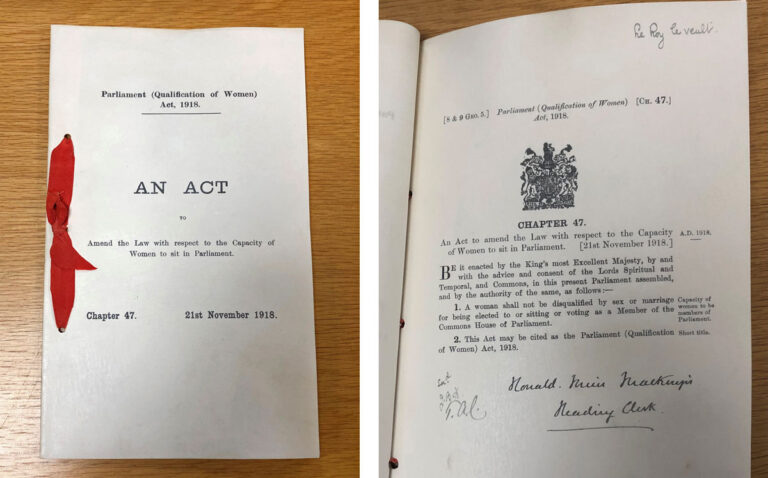

This blog post marks the anniversary of the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act, which passed on 21 November 1918, and enabled women over the age 21 to stand for Parliament.

While an often overlooked act, this change in the law represents an important milestone for women’s rights. For the first time in history, women were able to directly influence Parliamentary debates and the passing of laws.

Drawing on records from the Office of Works and the press, this blog post looks at how women’s admission to the House of Commons impacted the masculine structure of Parliament and traces the experiences of the pioneering women elected as MPs after the act was passed.

Debating the act

When women over 30 who met a property qualification won the right to vote in February 1918, there was confusion as to whether women could now be MPs. As a result, the Liberal MP Herbert Samuel introduced a resolution on 23 October 1918 which would allow women to stand for Parliament.

Samuel argued that it was ‘the natural consequence’ now that some women could vote, and emphasised that the ‘woman’s point of view’ should be heard in Parliament by women, rather by men claiming to represent women’s views (see footnote 1). It was also believed that women had a ‘special knowledge’ of issues related to the home and social reform which would benefit Parliament, particularly in the aftermath of the First World War.

Some politicians remained hostile to the idea of women MPs. The Conservative MP Hedworth Meux declared ‘I say that no woman is fit by her physical organisation to stand the strain of Parliament’ (see footnote 2). However, the response to the bill was largely positive and it passed with little opposition.

While the act was just 27 words long, its impact was huge – for the first time in history, women’s voices could be directly heard in the House of Commons. The act read ‘A woman shall not be disqualified by sex or marriage for being elected to or sitting or voting as a Member of the Commons House of Parliament’ (see footnote 3).

Interestingly, there was no age restriction for women standing for Parliament. From the age of 21 women could fight seats on the same terms as men, even though women aged under thirty remained disenfranchised under the terms of the 1918 Representation of the People Act. This resulted in numerous women standing for election before they could vote themselves over the subsequent decade.

Facilities for women in Parliament

This change in the law was swiftly followed by debates about the need for female facilities in Parliament, as the structures and surroundings of Westminster ‘were largely man-made’, and at the time, did not adequately cater for women (see footnote 4).

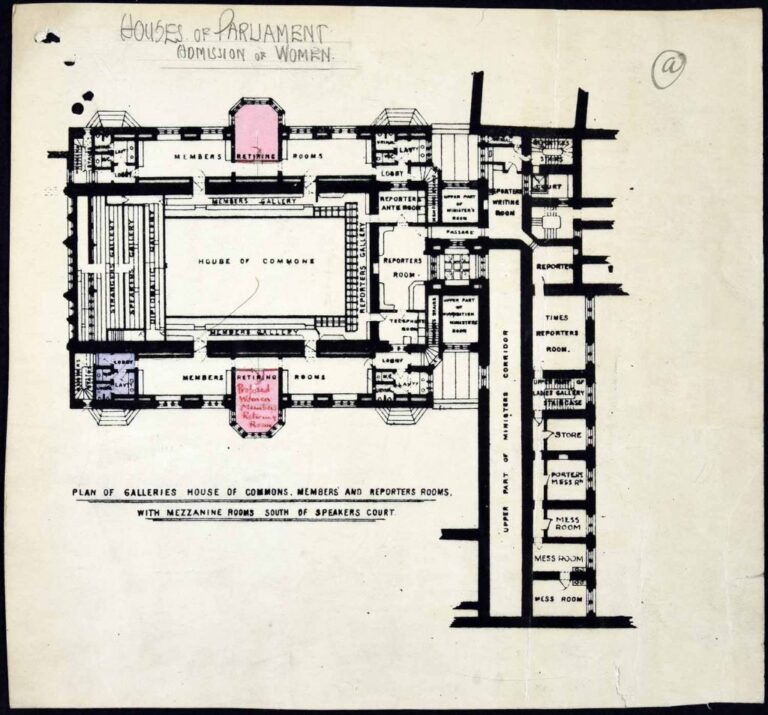

Discussing women’s admission to the House of Commons in 1918, a memorandum produced by the Office of Works stated that:

‘In connection with the Motion which has been passed that women should be eligible as Members of Parliament, it is necessary to make certain arrangements, which are rather difficult at the present time owing to the fact that the numbers of women who are likely to be returned to the House are not known.’

Memorandum titled Houses of Parliament. Admission of Women to the Legislature, 1 Nov 1918, WORK 11/237

Various proposals were submitted concerning provisions for female bathrooms and a woman members’ room. The idea of a woman only dining room was also discussed, although it was suggested that ‘perhaps in many cases the women members would use the same Dining Room as the existing members of the House’, although this did not materialise (see footnote 5).

It was proposed that a woman’s bathroom could be provided where the blue coloured room is on this diagram, as ‘all that would be necessary would be the taking out of the urinals in the lavatory and making provisions on further W.C.’ (see footnote 6).

Catalogue ref: WORK 11/237

Furthermore, a woman member’s room was suggested and is coloured in pink at the bottom of the diagram, its name highlighting the perceived strangeness of MPs who were not male. This space provided a place for women MPs to work in between Parliamentary debates.

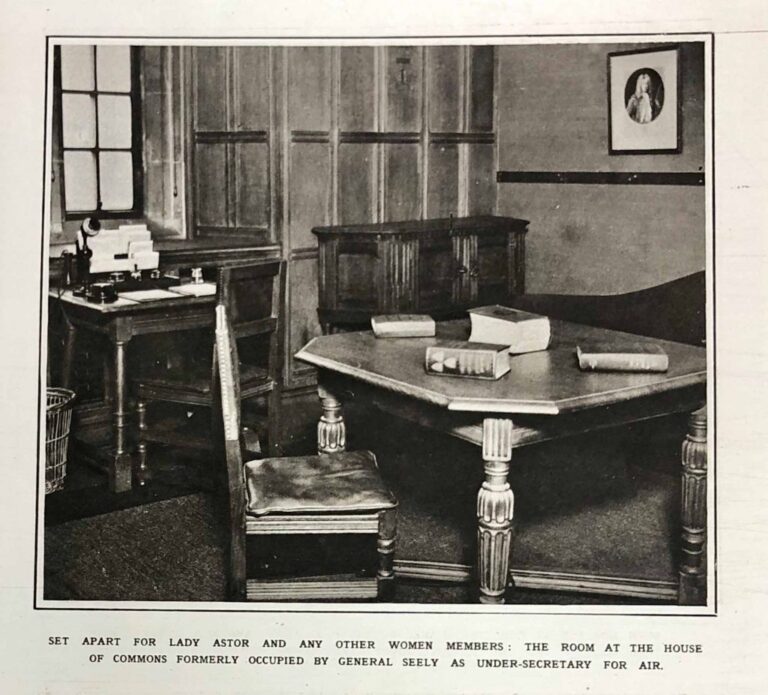

As more women entered the House of Commons during the interwar period, female MPs across the political spectrum shared the woman members’ room. The room became known as the ‘tomb’ as it was cramped and poorly furnished (see footnote 7).

Nonetheless, the woman members’ room helped to foster a degree of solidarity between women MPs, especially as they were excluded, both directly and indirectly, from other spaces open to male colleagues such as the Strangers’ Dining Room, the smoking rooms, and the bars, all places where informal political work took place which disadvantaged women.

Women’s experiences in Parliament

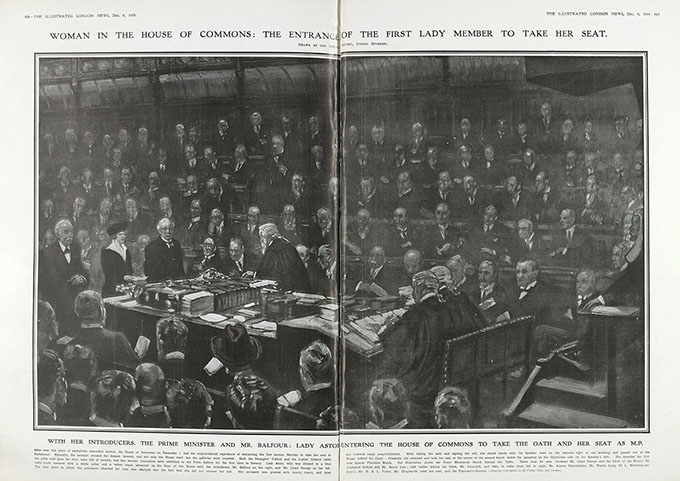

In 1919, American born society hostess Nancy Astor won a Plymouth Sutton by-election for the Conservative Party, becoming the first woman MP to take her seat in the House of Commons. Her election success made headlines around the world and represented a new era for British politics. Parliament was no longer a male-only space.

However, she was not the first woman to be elected. In the 1918 General Election, seventeen women across the political spectrum stood for election (see footnote 8). The Sinn Féin candidate for Dublin St Patrick’s, Constance Markievicz, was the only woman to win her election contest, but along with other Sinn Féin MPs, she was not prepared to take the oath of allegiance to the British crown and refused to take her seat in the House of Commons.

Astor entered Parliament for the first time on 1 December 1919. The House of Commons chamber was full with 707 MPs, who were all keen to witness the arrival of the first woman MP (see footnote 9).

Dressed in a simple white blouse, black skirt, and jacket, paired with a tricorn hat, Astor was introduced into the chamber by her sponsors Arthur Balfour and David Lloyd George. She adopted plain clothing in the hope of avoiding scrutiny on her appearance and clothing choices, although the press continued to comment on it. In the lead up to Astor’s arrival, The Globe declared ‘When Lady Astor takes her seat in the House, the burning question for the moment is likely to be what she will do with her hat’, while the Dundee Courier subsequently described Astor’s appearance as ‘the picture of vigorous British womanhood’ (see footnote 10).

This image from the London Illustrated News emphasises how much Astor stood out in the chamber as the sole female MP. Astor later revealed ‘that although she had given the appearance of composure, on her first day she had been absolutely terrified and sat in the House ‘for five hours without moving’ for fear of drawing attention to herself (see footnote 11).

As Rachel Reeves notes, ‘the very act of physically taking her seat was a challenge: since it was in the middle of a row, male MPs… often physically obstructed her from getting through (see footnote 12). She received a largely hostile reaction from male MPs, with Astor famously saying that members ‘would rather have had a rattlesnake than me’ in the House of Commons (see footnote 13). Many MPs refused to speak to Astor, including her friend Winston Churchill who said that by ignoring her, we ‘hoped to freeze her out’ (see footnote 14).

Outside of the debating chamber, Astor confined herself to the woman members’ room. As the only woman MP until the Liberal Margaret Wintringham entered in 1921, Parliament was often an isolating experience for Astor. Reflecting on this, she remarked ‘Pioneers may be picturesque figures, but they are often rather lonely ones’ (see footnote 15). Despite belonging to different parties, Astor and Wintringham became close friends and worked together on issues related to women and children. On entering Parliament, Wintringham spoke of feeling ‘rather like a new girl at school’ in her maiden speech (see footnote 16).

As more women entered Parliament, they shared the woman members’ room. Indeed in 1927, eight women were sharing its three desks, two armchairs, two sofas and one small mirror (see footnote 17).

Over time, women MPs began to challenge the masculine structure of Parliament. When the Labour MP Ellen Wilkinson was elected in 1924, she decided to enter the smoking room, but was stopped by a male police officer who told her that ladies did not enter such a space. To this she replied, ‘I am not a lady – I am a ‘Member of Parliament’, before opening the door’ (see footnote 18).

Wilkinson continuously drew attention to the limited accommodation for women MPs in the House of Commons. This, she told the press in 1928, was because ‘women MPs are regarded as a mere political accident’. She went on to say that ‘the authorities really ought to face up to the question of providing permanent and satisfactory accommodation’ (see footnote 19).

The passing of the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act marks an important moment in history for women’s rights. However, rather than Parliament trying to adapt to integrate women into Parliamentary spaces, separate spaces were created for women, which had a significant impact on how female MPs would experience Parliament. Nonetheless, the challenges that women faced brought about a sense of solidarity between women MPs across the political spectrum.

Footnotes

- HC Deb, 23 October 1918, vol 110, c815

- HC Deb, 23 October 1918, vol 100, c851

- Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act, C 65/6394, The National Archives

- Elizabeth Vallance, Women in the House: a study of women members of Parliament (London, 1979), p. 129

- Memorandum titled Houses of Parliament. Admission of Women to the Legislature, 1 Nov 1918, WORK 11/237, The National Archives

- Memorandum titled Houses of Parliament. Admission of Women to the Legislature, 1 Nov 1918, WORK 11/237, The National Archives

- UK Parliament, ‘Voice & Vote: Women’s Place in Parliament exhibition’, https://www.parliament.uk/get-involved/vote-100/voice-and-vote/ (accessed 4 November 2022)

- For more information on women candidates and the 1918 General Election, see Lisa Berry-Waite, ‘The ‘Woman’s Point of View’: Women Parliamentary Candidates, 1918-1919’, in David Thackeray and Richard Toye, eds, Electoral Pledges in Britain since 1918: The Politics of Promises (Cham, 2020), pp. 47-69

- Sophy Ridge, The women who shaped politics: empowering stories of women who have shifted the political landscape (London, 2017), pp. 92-93

- ‘Commons’ “Boudoir”: Minister’s Room For Lady M.P’s Own Use’, The Globe, 28 November 1919, p. 2; ‘Tumult of Cheers for Lady Astor’, Dundee Courier, 2 December 1919, p. 8

- Rachel Reeves, Women of Westminster: the MPs who changed politics (London, 2020), p. 16

- Rachel Reeves, Women of Westminster: the MPs who changed politics (London, 2020), p. 15

- BBC, ‘Interview with Nancy Astor’, 1956, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01lfw2p (accessed 2 November 2022)

- BBC, ‘Interview with Nancy Astor’, 1956, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01lfw2p (accessed 2 November 2022

- Nancy Astor, My Two Countries (New York, 1923), p. 5

- HC Deb, 9 November 1921, vol 148, c466

- Krista Cowman, Women in British Politics, c.1689-1979 (Basingstoke, 2010), p. 124

- Rachel Reeves, Women of Westminster: the MPs who changed politics (London, 2020), p. 26

- ‘Insufficient Accommodation at Westminster’, Gloucester Citizen, 21 March 1928, p. 6

A very valuable and timely blog which quite rightly celebrates the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act.

A few years ago, I watched some interesting black and white, silent newsreel showing Nancy Astor talking to workers in Plymouth Sutton. The film was part of an exhibition at Plymouth Museum and Art Gallery (now The Box). At the time, I suggested to the exhibition organiser that a lip reader might be employed to translate what Astor was saying on camera. To my knowledge, this wasn’t done at the time due to resource constraints. But you might find that it is worth pursuing as part of your research.

Thanks for your comment and for recommending the newsreel.

Thankyou for this interesting edition covering the first entrance of women into the House of Commons.

I was born in England in 1926, into a household where we were all given equal voice. I have now lived in Australia for many years and world politics is still a strong interest of mine. Women have progressed mightily during these years but politically they still have a long way to go.

Fascinating blog, nice to see such details about what women faced even after going through campaigning, etc. Is anyone working on the history of women in British Isles who were elected to local councils, as Poor Law Guardians, and school boards from the last quarter of the 19th century onward? A colleague and I are working on the history of US women elected to local and state offices before 1920 (when women gained the right to vote). The earliest woman we have found so far was elected to a county-wide position in 1853. Would love to hear from others interested in the topic of the history of women elected to political offices world-wide.

Thank you for your comment. If you’re interested in women and local government in Britain, I’d recommend the book ‘Ladies elect: women in English local government, 1865-1914’ by Patricia Hollis. It offers a comprehensive study on the topic and covers a range of areas, from the poor law and school boards, to the London County Council and borough councils.

A fascinating insight into the beginnings of female MPs, clearly showing the prejudice against them. Why the need to segregate? Things are changing but not fast enough- blatant discrimination and bullying are still rife. Until females hold the majority of seats this will not be resolved.