The events at St Peter’s Fields in Manchester in August 1819, known as the ‘Peterloo’ Massacre, are well documented. The National Archives holds a wealth of archival material describing what happened on the day and its aftermath. The National Archives and Royal Holloway, University of London, have collaborated recently on a Heritage Lottery Fund project, Archives Alive: Peterloo, to bring some of these documents to life by recording actors performing them. The videos will launch on Friday 16 August, 200 years to the day after the Massacre, on the Royal Holloway Citizens Project’s YouTube channel.

However, Peterloo was not an isolated episode of civil unrest during the late 1810s and 1820s. Britain had defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 but winning the peace in the following years proved to be a challenging task for the government.

In 1816, Britain was faced with the task of rebuilding the country after years of war. Lack of parliamentary representation, poor harvests, depressed trade and the demobilization of thousands of servicemen all contributed to a period of economic distress and unrest for which Lord Liverpool’s government was ill-prepared.

Throughout the 1820s, there were many further incidents which threatened the peace and stability of the country. Some of those involved in these events were punished through the courts and their only recourse against harsh sentences was to petition for mercy.

The petitions for mercy are a treasure trove – unique records detailing the lives of ordinary subjects who became entangled with the law. Petitioning for the exercise of the Royal Prerogative of mercy was the only avenue of relief for convicted prisoners, as a Court of Criminal Appeal was not established until 1906.

By researching the petitions for mercy held at The National Archives in the record series HO 17, we can shed light on these other disturbances which have been largely neglected by historians.

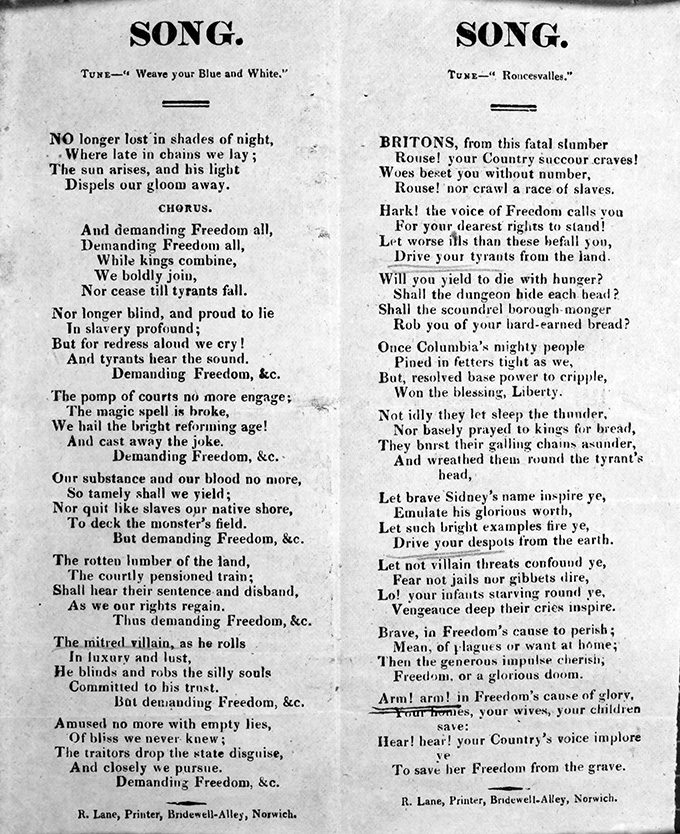

Broadside sheet printed by R Lane with two seditious songs from Norwich. These were sent by Thomas Coldwell of Norwich Post Office to the General Post Office Secretary as examples of seditious publications that ‘inflame the minds of the lower class of people’, 10 July 1820. (Catalogue reference HO 33/2/52 f167)

Yorkshire Rebellion

In April 1820, after cuts to their wages and the introduction of labour-saving mechanical processes, an armed force of 400 weavers from The Barnsley Union marched towards Huddersfield, where they expected to join up with a large group of insurgents from the surrounding areas. Waiting for them were only about 20 members but more importantly, so were the local militia who arrested 17 of them. Charged with high treason, these weavers were arraigned at York Summer Assizes in 1820. After a plea bargain, the capital sentences were commuted (reduced) to various periods of transportation and imprisonment.

The consequences of this aborted uprising continued to reverberate around the country with Edward Baines, the editor of the Leeds Mercury newspaper, leading a determined campaign to persuade the government to pardon the prisoners. This was partially successful, as the prisoners, who were too ill or infirm to be transported and still languished in York Castle gaol, were pardoned two years later. The transported convicts, however, remained in Van Diemen’s Land (modern day Tasmania)[ref] Catalogue reference: HO 17/122/47[/ref].

The Cinderloo affair

In January 1821, due to a depression in the iron trade, employers at iron works near Shrewsbury cut workers’ wages from 15s (shillings) to 12s a week. 3,000 workers retreated to cinder hills near Dawley and threatened violence. Two troops of local yeomanry were called out and the Riot Act was read, but this did not prevent the soldiers being pelted with stones and bricks. In the ensuing melee, two miners were killed when the soldiers fired on the mob.

The ringleaders, Thomas Palin and Samuel Hayward, and five protesters were arrested. At Shropshire Lent Assizes in 1821, Palin and Hayward were capitally convicted (sentenced) to death and the other prisoners were sentenced to terms of imprisonment.

Palin was hanged on 7 April but favourable circumstances were found for Hayward and his sentence was commuted to transportation for life. The riot was known locally as ‘the Cinderloo affair’, an ironic reference to the event at St Peter’s fields. Less than a year later, the visiting magistrates at Shrewsbury petitioned Robert Peel, the Home Secretary, for Hayward’s release, citing his good conduct in prison and the impact Palin’s execution had on Hayward and the other offenders. Unlike the Yorkshire weavers who petitioned unsuccessfully, this endorsement by the local visiting magistrates carried sufficient influence for Peel to recommend that a pardon for Hayward should be granted[ref] Catalogue reference: HO 17/67/49[/ref].

Rossendale Rebels

In 1826, thousands of Lancashire cotton workers took up arms in protest against the introduction of power looms and subsequent lowering of wages for hand weavers. During four days of rioting, the mob destroyed more than 1,000 looms and caused widespread damage to cotton mills.

The disorder was only quelled when the artillery arrived. Several rioters were killed by the militia during the disturbances and more than 60 of the protesters were arrested.

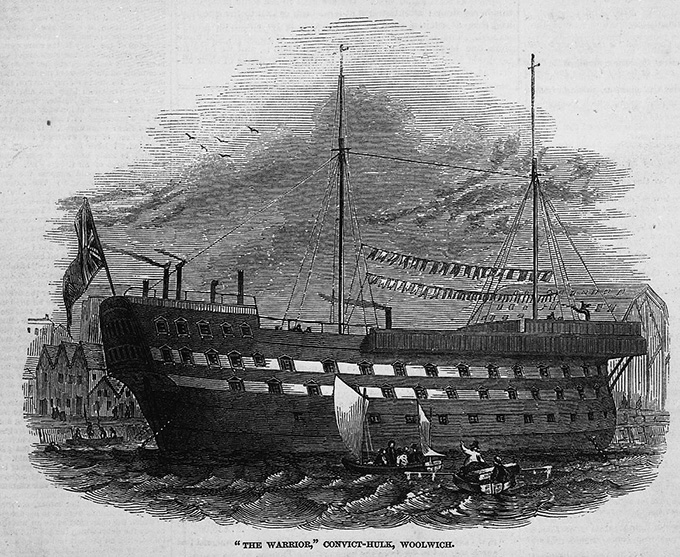

Convict hulk ‘Warrior’ at Woolwich 1846. Many men sentenced to transportation would have languished in these fetid, floating prisons. (Catalogue reference: ZPER 34/8)

Forty-two weavers were capitally convicted of riot and destroying looms. All the death sentences were commuted with the majority being transported for life. In his circuit letter, Mr Justice Park took the unusual step of setting out his reasons for commuting the sentences[ref] Catalogue reference: HO 6/10[/ref]. The most compelling reason, in his view, was that no personal violence was involved.

Isaac Hindle was one of the prisoner’s transported to Van Diemen’s Land. His widowed mother petitioned the Crown, begging that her son remain in the country as she was dependent upon him and was distressed that she would never see him again[ref] Catalogue reference: HO17/122/Yl 48[/ref]. Her pleas were unsuccessful.

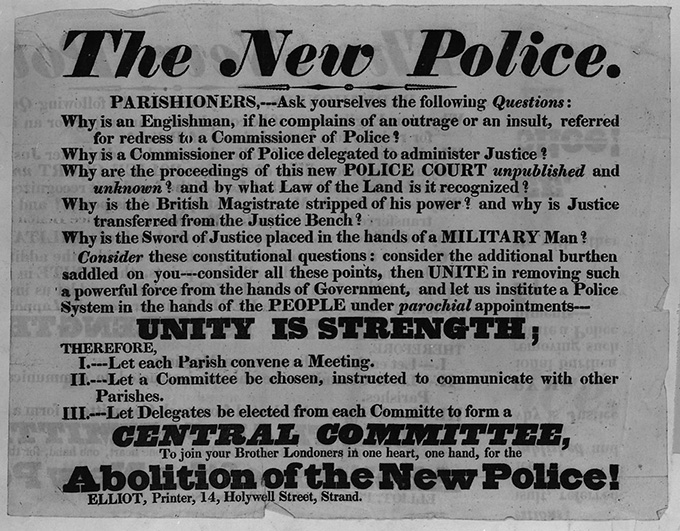

Although Peel’s establishment of the Metropolitan Police is now seen as a success, at the time it generated significant opposition, evidenced by this anti-police handbill, printed in London, 1830. (Catalogue reference: HO 61/2)

After the events at Peterloo, the government’s response to winning the peace was to pass the Six Acts, considered to be some of the most draconian and repressive measures ever implemented. Ten years later, the landscape had changed.

One positive outcome of these episodes of civil unrest was that it became increasingly difficult for the government to justify employing the militia to quell the disturbances. Robert Peel’s attempt to establish a civilian police force in London in 1822 had been firmly rejected by parliament, but by 1829 his Metropolitan Police bill was passed with little dissent.

Perhaps the enduring legacy of Peterloo and the other skirmishes during this period was that, in future, peace was kept by a civilian police force rather than the militia based on the Peelian principle of policing with ‘public approval’.

Dr Brenda Mortimer (LlB (Hons), Ph.D, Solicitor) is a volunteer at The National Archives, and also helped to transcribe archival material for use in Archives Alive: Peterloo.

The picture of the petition for clemency for Samuel Hayward by his father is for another Samuel Hayward, in London. (as I am a Cinderloo 1821 Remembered family History researcher, I have been looking at newspaper reports of the time, and the name and offence has come up in several searches)

I was pleased to find that the relevant images from HO13 have been digitised and made available by Find my Past – Source Correspondence And Warrants

Piece number 36

Page number 337 reply to the Mayor of Shrewsbury’s petition 4 april 1821

and

Piece number 38

Page number 177-178 record of the letter of free pardon sent to the relevant authorities.

It was fascinating to find the signature of Robert Peel on the second set of diary pages.

Maybe we will eventually have a chance to visit and read the Wellington Magistrates petition at HO17/67/49 for ourselves. I wonder if the original petition from April 1821 is still in existence?

I hadn’t realised that other rebellions took place possibly as a consequence of Peterloo. When one reads the conditions and particularly the cut in wages the protesters were subject to it is difficult not to feel sympathy for them. The fact that the protests were subdued with military force is shocking in view of the number of protesters killed as a result. Negotiation would have perhaps been an answer but no such facility existed and certainly the employers would not have agreed. The workers had leading supporters but these were “enemies of the state” and as such disposed of.

Thank you Mrs Stocks for pointing out the mistake and apologies for taking so long to correct it, we have removed the incorrect image and the caption that went with it.

Unfortunately, the April 1821 petition from the inhabitants of Shrewsbury does not survive but some traces of it can be found in the records digitised on Findmypast. The April 1821 letter to the Mayor of Shrewsbury that you found copied in HO 13 acknowledges receipt of this petition and says that it was considered for Palin but refused. Hayward had already been reprieved by the Judge, whose recommendation for mercy can probably be found in the series HO 6 (this series is not available online). The HO 19 registers of petitions do record a petition on behalf of Palin that was refused. The date of receipt is not recorded in HO 19 but it was given the reference WG 27, consistent with petitions received in 1821, which do not survive. Although there is no way to know for sure, it seems probable that this was the petition from Shrewsbury. The 1822 correspondence about Hayward at HO 17/67/49 is registered separately, with the reference MH 1, and includes the letter from the Wellington magistrates pleading that Hayward’s sentence of life transportation is pardoned.