This month sees the release of Ralph Fiennes’ film ‘The White Crow’, written by BAFTA-winning screenwriter David Hare. The movie tells the story of legendary dancer Rudolf Nureyev, focusing on his upbringing and his love affair with dance, building up to the extraordinary moment of his defection at the height of the Cold War.

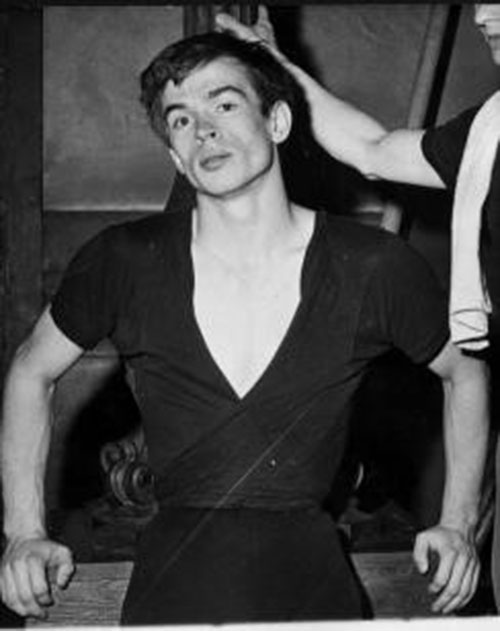

Press photo of Rudolf Nureyev at his defection from the Soviet Union in 1961. Source: Wikimedia Commons

16 June, 1961: members of the Kirov Ballet company were gathered at Le Bourget Airport in Paris, ready to fly to London, the next stop on their cultural tour representing the Soviet Union. Among them was Rudolf Nureyev, a 23-year-old dancer who had been astonishing Western audiences and delighting critics with his athleticism, technique and extraordinary dedication to the art form.

Early life

Nureyev was born into a Tatar family, the youngest of four children. His birth took place aboard a train on the trans-Siberian railway, and he spent his early years living in Ufa. He was a prodigy who fell in love with dance at the age of six – despite the disapproval of his father, who tried to forbid him from going to lessons.

His passion for dancing and unrelenting dedication won him a place at the Kirov Ballet in Leningrad (now St Petersburg). In 1959 he was permitted to travel to Vienna and dance at the International Youth Festival, but he was rebellious by nature and persistently defied rules. His behaviour in Vienna prompted the Soviet Ministry of Culture to tell him he would not be allowed to travel abroad again

However, the French organisers of the Kirov Ballet’s tour saw him perform in Leningrad in 1960. Deeply impressed by his skills, they petitioned the Soviet authorities to allow him to travel. He was eventually granted permission, but Soviet ‘watch-dogs’ kept a close eye on him.

Breaking the rules

While in Paris, Nureyev ignored the rules against mixing with foreigners. He also allegedly visited gay bars and clubs. At the time, same-sex physical relationships between men were illegal in the Soviet Union, and punishable by up to five years’ hard labour in prison. But Nureyev found himself in a much more liberal environment in France, where male-male relationships were legal over the age of 21 (although indecent exposure legislation was sometimes used to target gay and bisexual men).

The Kirov Ballet management and their KGB handlers were worried by his behaviour and wanted to send him home. Konstantin Sergeyev – artistic director of the company – told Nureyev privately that, instead of going to London, he needed to return to Moscow: his presence was required at a special gala performance in the Kremlin. Nureyev, whose relationship with Sergeyev had recently become increasingly rocky, was wary and refused to go.

‘I want to be free!’

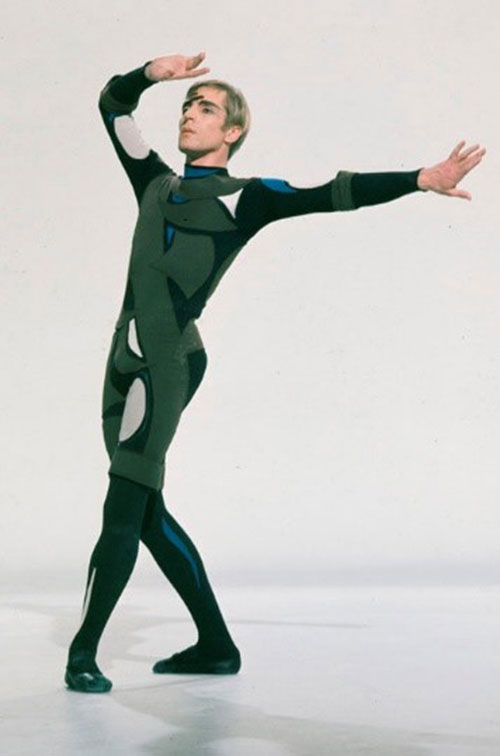

Dancers Liliana Cosi and Rudolf Nureyev, Italian show at Teatro 10, Rome. April 1972. Source: Wikimedia Commons

More pressure was piled onto the defiant Nureyev. He was told that his mother was seriously ill, and he needed to return home immediately to the Soviet Union to see her. Once more, Nureyev refused. By this time his suspicions were thoroughly aroused. He feared that returning to the Soviet Union would result in his being arrested and imprisoned; at the very least, he felt that he would never be allowed to return to the West.

At that moment he seemed isolated and alone. However, his Parisian socialite friend Clara Saint – daughter of a Chilean painter living in Paris – was luckily present at the airport. She helped him by informing the French police of his predicament. He managed to escape from Russian embassy guards and ran through a security barrier, shouting in English, ‘I want to be free!’

Finding sanctuary

After his dramatic defection, Nureyev was given permission to stay in France. Soviet officials worked hard to blacken his name, and in his absence he was sentenced to prison. However, within a week Nureyev had found sanctuary with the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas, who signed him up to perform ‘The Sleeping Beauty’ with prima ballerina Nina Vyroubova.

Vyroubova had been born in the Crimea, but her family had fled from the Russian Revolution: she had lived in Paris ever since childhood. At first, she and Nureyev seemed well matched. But Nureyev – never one to stick to the rules – added his own steps to the choreography for his final solo. This enraged his dancing partner, and she refused to speak to him for five years.

Nureyev in the files

In our collection is a Foreign Office file which deals with Nureyev’s defection: FO 924/1399.

The documents in the file are largely concerned with the reactions of Victor Hochhauser, the promoter who had arranged for the Kirov company to perform at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden – their first visit to the UK. He was worried about Nureyev appearing in ‘The Sleeping Beauty’ in Paris in the same role that he was meant to have performed in Covent Garden, at the same time. Foreign Office official R L Speaight writes:

The Kirov Company are under contract to Mr Hochhauser to produce certain specified dancers including Nereyev at Covent Garden so that he can take proceedings against them for breach of contract. He does not wish to do this since it would help no one and only cause ill-feeling.

His comments show just how unexpected Nureyev’s defection was. It was not prompted by political ideology – his first and foremost passion was always ballet. Speaight describes how Hochhauser and the Kirov Ballet management responded to the defection:

Mr Hochhauser tells me in strict confidence that both the Kirov Ballet and the Soviet Charge d’Affaires are shocked at the way the Soviet security people handled Nereyev and still have hopes of getting him back. Apparently Nereyev had no intention of seeking political asylum and no interest in political matters: his whole life is bound up with the ballet and his greatest ambition was to appear at Covent Garden. In Paris he became rather too friendly with people whom the Party frowned upon (presumably emigres) and the watch-dogs attached to the Company decided to send him home. Nothing was said to him until the Company reached the airport to fly to London. When the watch-dogs tried to take him away he very naturally reacted as reported in the press.

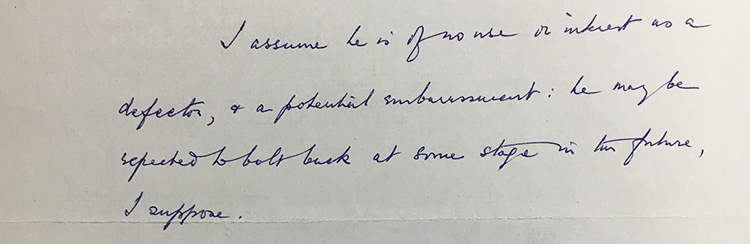

The Foreign Office officials had a few, fairly curt remarks to make about the possible value of Nureyev as an asset:

I assume he is of no use or interest to us as a defector, and a potential embarrassment: he may be expected to bolt back at some stage in the future, I suppose.

FO 924/1399: Nureyev’s potential value as an asset is assessed by the Foreign Office

Nureyev in the West

They may have been familiar with some of the key players in the drama, but they were wrong about Nureyev, who was to remain based in the West for the rest of his stellar career. He had a dazzling repertoire, and became well known for his enduring relationship with the Royal Ballet. As well as finding fame as a dancer, he also became a successful producer and choreographer. He was granted Austrian citizenship in 1982, and ultimately became artistic director of the Paris Opera Ballet.

Danish dancer Erik Bruhn. Attribution: Riksantikvarieämbetet / Pål-Nils Nilsson, CC-BY. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Sweden licence

Not long after his defection, Nureyev met Erik Bruhn, a soloist at the Royal Danish Ballet. He had seen Bruhn in an amateur film, and deeply admired his performance. The two dancers fell in love: theirs was sometimes a volatile and tempestuous relationship, but they stayed close for many years until Bruhn’s death in 1986.

Nureyev tested positive for HIV in 1984. Initially, he refused to allow it to prevent him from performing, but over the next few years it steadily took its toll on his health and his career. He died in France at the age of 54 on 6 January 1993. His funeral was held in the foyer of the Paris Garnier Opera House, and he is buried in a cemetery not far from the city which gave him sanctuary.

Find out more

You can find out more about the relationship between the Soviet Union and the West during this turbulent time in history by following our Cold War season: it launches on 4 April on the 70th anniversary of the formation of NATO and runs until the end of November, and the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Look out for our Cold War-themed events, blogs and social media posts. And don’t miss our in-house exhibition, Protect and Survive: Britain’s Cold War Revealed.

A very clear and interesting account: thank you.

Hello! I loved this film; stunning performances. Better than St Leonard’s senior drama even…if that’s not too provocative…KC