In 1985, at the height of the Thatcher era, officials in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) carefully considered the many uncomfortable questions brought up by the 40th anniversaries of the Yalta and Potsdam Agreements. It became apparent to senior FCO staff that any discussion of the historic implications of these events should be restricted to internal circulation.

Photograph of the ‘Big Three’ at Yalta; British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, US President Franklin D Roosevelt and Soviet Premier Marshal Josef Stalin, flanked by their respective military chiefs and political advisors, at the Livadia Palace during the Yalta Conference, 4 February 1945. Catalogue ref: INF 14/447

Record FCO 33/8016 contains correspondence between senior government department heads arguing the complexities of the anniversaries of the Yalta and Potsdam conferences. This file also includes a copy of the press statement issued by the Reagan White House to mark the 40th anniversary of Yalta, together with memoranda compiled by the FCO Research Department addressing the controversial issues raised by these anniversaries. Derek Thomas, the then Deputy Under-Secretary for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs and the Head of the Europe and Political Directorate, advised that ‘any suggestion of stimulating debate on the issues’ be avoided (FCO 33/8016). Whitehall sensed that to contribute to any public discourse on the legacy of Yalta and Potsdam would be to open a can of worms.

Confidential FCO internal minute on Yalta and Potsdam Agreements, 13 May 1985. Catalogue ref: FCO 33/8016

The internal discussions of the FCO with other government departments, including the Ministry of Defence and the Prime Minister’s Office, would therefore concern the appropriate handling of the ‘40th anniversary’ debate. Already, a lively public discourse had been provoked by the publication of a significant article in Foreign Affairs by Zbigniew Brzezinski, the Polish-born former National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter. Entitled ‘A Divided Europe: the Future of Yalta’, Brzezinski’s piece asserted that much of the ‘current preoccupation’ with the legacy of the Yalta Conference was focused mainly on the ‘myth’ of Yalta, ‘rather than on its continuing historical significance’:

‘The myth is that at Yalta the West accepted the division of Europe. The fact is that Eastern Europe had been conceded de facto to Josef Stalin by Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill as early as the Tehran Conference (in November-December 1943), and at Yalta the British and American leaders had some half-hearted second thoughts about that concession. They then made a last-ditch but ineffective effort to fashion some arrangements to assure at least a modicum of freedom for Eastern Europe, in keeping with Anglo-American hopes for democracy on the European continent.’[ref]Zbigniew Brzezinski, ‘A Divided Europe: the Future of Yalta’, Foreign Affairs, Volume 63, Number 2 (Winter 1984/85), pp. 279-302, p. 279.[/ref]

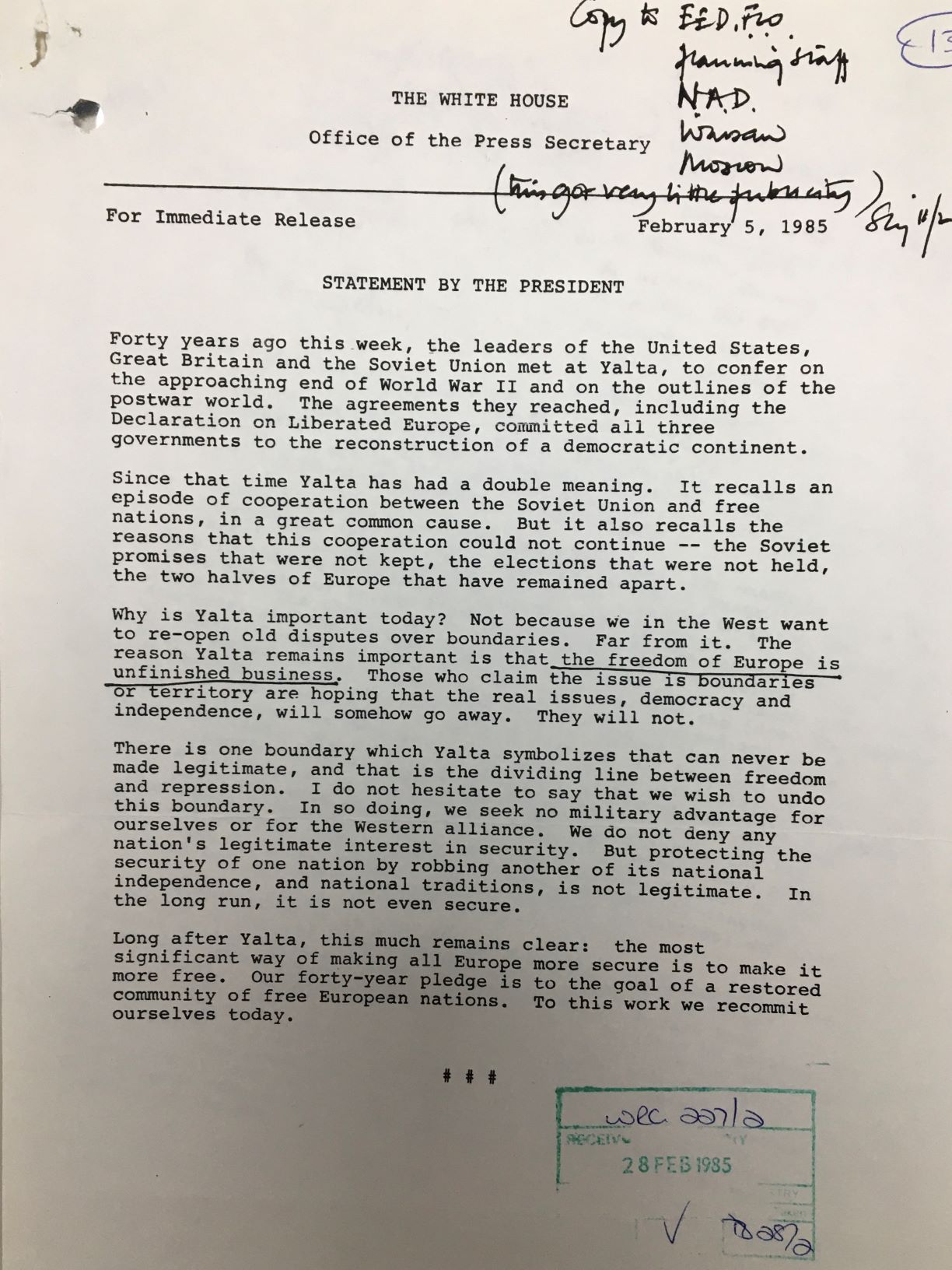

Three months earlier, on 5 February 1985, US President Ronald Reagan issued a press statement to mark the 40th anniversary of the opening of the Yalta summit. Reagan’s remarks, at variance with Brzezinski’s conclusions on the misperception of the Yalta legacy, emphasised the continuity of this legacy in terms of what the Western powers perceived as a Soviet pledge made at Yalta, namely, towards ‘the reconstruction of a democratic continent’ (FCO 33/8016):

‘Since that time, Yalta has had a double meaning. It recalls an episode of cooperation between the Soviet Union and free nations, in a great common cause. But it also recalls the reasons that this co-operation could not continue − the Soviet promises that were not kept, the elections that were not held, the two halves of Europe that have remained apart.

Why is Yalta important today? Not because we in the West want to reopen old disputes over boundaries; far from it. The reason Yalta remains important is that the freedom of Europe is unfinished business. Those who claim the issue is boundaries or territory are hoping that the real issues – democracy and independence – will somehow go away. They will not.’

– President Ronald Reagan, 5 February 1985 (FCO 33/8016)

Copy of US President Ronald Reagan’s press statement on Yalta, 5 February 1985. Catalogue ref: FCO 33/8016

Forty years after the ‘Big Three’ leaders concluded the ‘Protocol of the Proceedings of the Yalta Conference’, the continent of Europe was still divided between Western and Soviet spheres of influence. Poland was then in the grip of an existential struggle, seeking full national independence and freedom from Soviet hegemony.

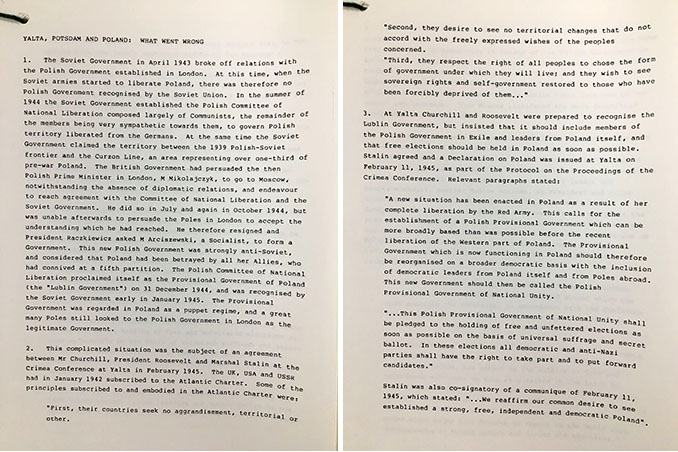

Thus, the 40th anniversary brought many controversial legacy issues into sharp relief. The fate of Poland was an issue to which the FCO Research Department would dedicate specific attention in their memorandum, ‘Yalta, Potsdam and Poland: what went wrong’ (FCO 33/8016).

Commencing with the Soviet government’s breaking of diplomatic ties with the Polish Government-in-exile in London in April 1943, Moscow had ceased to recognise any legitimate Polish authority. In August 1944, they formed the Polish Committee of National Liberation to govern the Polish state which was gradually falling to the conquering Soviet armies. The Polish Government-in-exile was firmly anti-Soviet, and when the Committee of National Liberation formed a Provisional Government of Poland, known as the ‘Lublin Government’, in December 1944, it was almost universally regarded as a puppet regime.

At the Yalta Conference, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and US President Franklin D Roosevelt were faced with a challenging situation. They could not recognise the Lublin Government in its current form, and were honour-bound to press for a Polish Provisional Government to include representatives of the London-based Polish Government until free and fair elections could be held and truly representative Polish government installed. In addition, the USSR had subscribed to the Atlantic Charter in January 1942. The first three principles of this charter, ratified by Britain and the US in 1941, were as follows:

First, their countries seek no aggrandizement, territorial or other;

Second, they desire to see no territorial changes that do not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the peoples concerned;

Third, they respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live; and they wish to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them; (FCO 33/8016)

What Churchill and Roosevelt now contemplated at Yalta would amount to a violation of all three principles. Not only were they prepared to recognise the Lublin Government in return for token concessions, but the two leaders were active participants with Marshal Stalin in bartering Polish territory without the consent of the Polish people and without any reference to their recognised representatives.

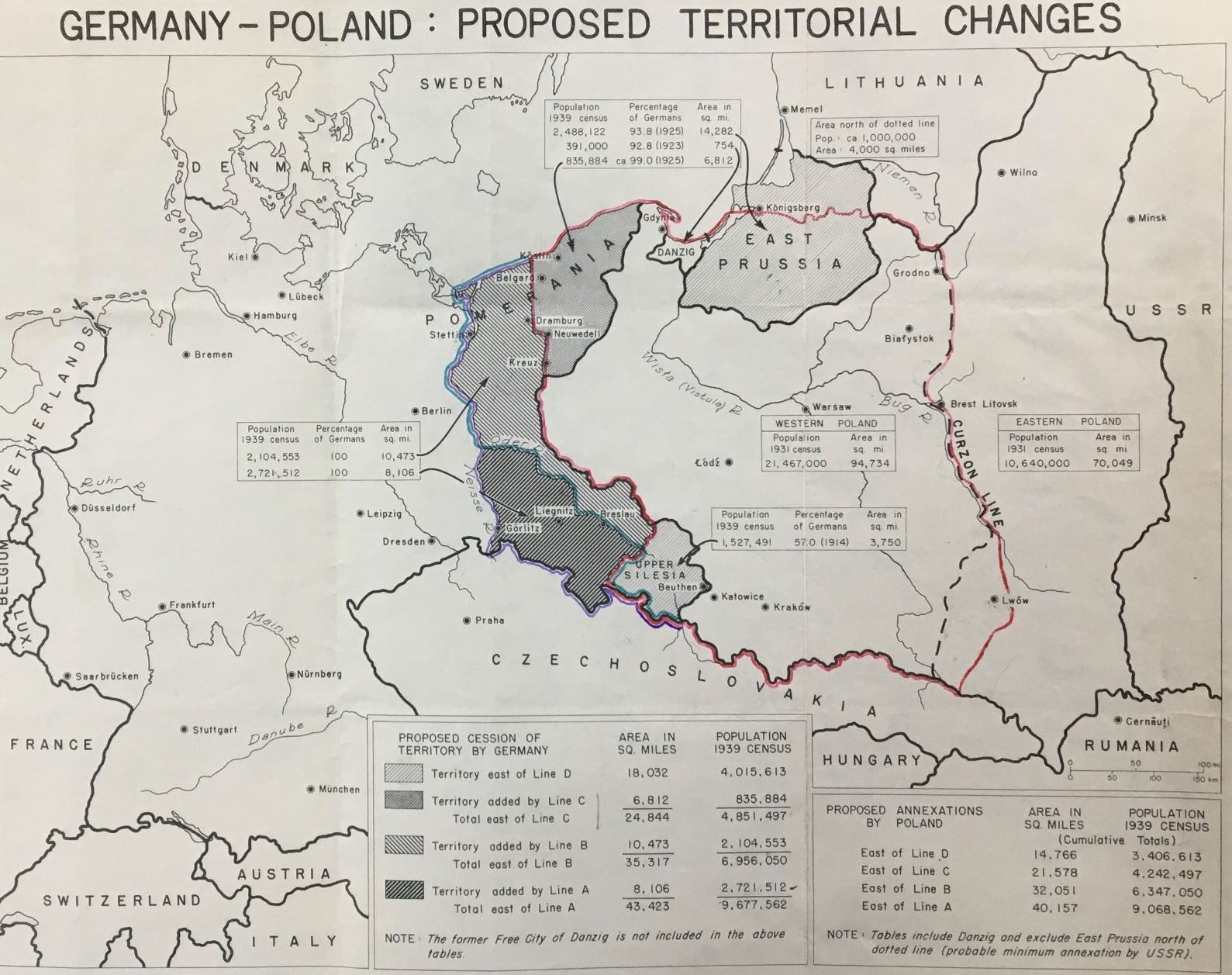

Eastern Poland would be ceded to the Soviet Union; almost a third of the pre-1945 Polish state, comprising over 70,000 square miles of territory, vanished at the stroke of a pen. The new Polish state would be compensated to the west by accessions of German territory, including Pomerania, Upper Silesia and most of East Prussia. Ultimately, the exchanges of territory would fall harder upon Germany, but the scale of the territorial transfers, together with inevitable exchange of populations that this would entail, was simply staggering. Poland would essentially be shifted 200 kilometres westwards on the map of Europe.

Map detailing the revised borders of the Polish state as agreed by the British, American and Soviet delegations at the Yalta Conference, February 1945. Catalogue ref: PREM 3/356/3

Despite the harshness of arrangements agreed on Poland’s future, neither Roosevelt nor Churchill were in a position to veto Stalin. Much of Eastern Europe had already fallen to Soviet forces, and Poland was now firmly in his grip and irretrievably embedded in the Soviet sphere. All that the British and Americans could do was to bargain for some arrangement where a vestige of western democratic values could be conceded to the Poles. The joint-statement issued by the three leaders at Yalta on 11 February 1945, known as the ‘Declaration on Poland’, became one of the key protocols of the Yalta Agreement and, to some extent, reflected the reality on the ground:

‘A new situation has been created in Poland as a result of her complete liberation by the Red Army. This calls for the establishment of a Polish Provisional Government which can be more broadly based than was possible before the recent liberation of the Western part of Poland. The Provisional Government which is now functioning in Poland should therefore be reorganized on a broader democratic basis with the inclusion of democratic leaders from Poland itself and from Poles abroad. This new Government should then be called the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity … This Polish Provisional Government of National Unity shall be pledged to the holding of free and unfettered elections as soon as possible on the basis of universal suffrage and secret ballot. In these elections all democratic and anti-Nazi parties shall have the right to take part and to put forward candidates.’ (FCO 33/8016)

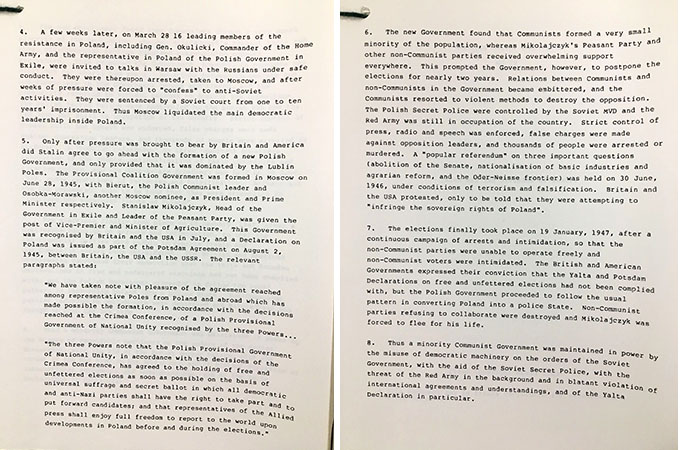

Just weeks later, on 28 March 1945, 16 leading members of the Polish resistance, including the Commander of the Polish Home Army, General Okulicki, and representatives of the Polish Government-in-exile, who had been invited to talks in Warsaw under a safe conduct, were arrested by the Soviet authorities. They were taken to Moscow and, after weeks of torture, were forced into confessing to anti-Soviet activities.

The timing of their show trial, from 18 to 21 June 1945, was carefully chosen to coincide with a conference on the composition of a new Soviet-backed Polish provisional government. Stalin had bowed to pressure from Britain and the US to honour his pledges at Yalta and, on 28 June, the Provisional Coalition Government of Poland was formed, albeit with a dominance of Lublin Government members.

The new government understood that they could not maintain their position in a general election, since Communists formed a very small part minority of the Polish population, whereas the Peasant Party and other non-communist political parties enjoyed strong support throughout Poland.

Thus, the elections would be postponed for nearly two years: the Communists, propped up by the Moscow-backed regime, used this period to destroy the opposition using violent and repressive measures. Press, radio and speech were subject to strict controls, opposition leaders were arrested under false pretenses and thousands of Poles were incarcerated or murdered by the Polish Secret Police, backed by Soviet security forces and the occupying Red Army. British and American objections against the imposition of a bogus referendum on the abolition of the Senate, the nationalisation of basic industries, agrarian reform and the acquisition by the Polish state of the Oder-Neisse frontier, were treated as an attempt to ‘infringe the sovereign rights of Poland’ (FCO 33/8016).

When elections finally took place on 19 January 1947, the outcome was easily decided by a government campaign of arrests and voter intimidation. The non-Communist opposition parties were obliterated and the leader of the popular Peasant Party was forced to flee. Britain and the US finally declared that Soviet pledges on free and fair elections made at Yalta, and later Potsdam, had not been complied with. By then the Cold War was underway, and the battle for Poland had been well and truly lost.

The outcome of the Yalta Conference, as observed by FCO officials on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the conference in 1985, was not a subject that the British government could afford to engage with, let alone commemorate. Unlike the Reagan White House, which chose to use the historic broken pledges of the Soviet Union as a rallying cry in a still ongoing propaganda battle against their Cold War nemesis, the Thatcher government would be haunted by the ghost of an old ally for whom Britain had gone to war in 1939. Communist control in Eastern Europe would eventually crumble and Poland emerged as a free nation four years later in the Revolutions of 1989.

FCO Memorandum: ‘Yalta, Potsdam and Poland: What went wrong’. Catalogue ref: FCO 33/8016

However, 75 years later, the Yalta Agreement is still remembered with great bitterness by Poles as a betrayal of their nation by the Western Allied powers. The fact that this event remains as contentious today as it was in 1985, during the climax of the Cold War, underlines its long-term impact on the face of Europe and upon the recent history of modern Poland.