As any Downton Abbey fan will know, the Dowager Countess of Grantham is a force to be reckoned with. Known for her sarcasm and wit and guaranteed to make any dinner party memorable, some of her ripostes are infamous. However, her remark that ‘there’s no such thing as an English heiress with a brother’ sums up centuries of English inheritance law. Read on to gain an insight into why the Dowager is right and what happens when there is no son to inherit an estate.

Manors could pass to new owners by inheritance, marriage or by sale. Some manor histories are relatively easy to reconstruct because manors remained in the same family for long periods, passing from father to son, or there is evidence of a clear sale record. However, other manor histories are much trickier to trace. Most often, this was because the manor was divided between coheiresses creating several parts or moieties of the manor to trace forward. The Cornish manor of Tremadart was spilt into nine moieties! (See footnote 1.) However, this only happened, as Lady Grantham states, when there were no male descendants.

Who inherits?

Inheritance followed English common law, which stated the eldest son should inherit. This was known as primogeniture. If the eldest son died without children, the next eldest male would inherit and so on. If there were no sons, then the estate would be divided, and all the daughters would inherit as coheiresses.

To complicate this further, deceased direct descendants could be represented by their children, as sons in age order, or daughters as coheiresses if there were no sons. If the estate was divided between coheirs, any children of a deceased daughter would represent their mother and would also receive a share or moiety, regardless of gender.

But what about an entail?

Returning to Downton Abbey, Lord Grantham had three daughters: Lady Mary, Lady Edith and Lady Sybil. Following common law, if he had a son, the son would inherit as a single heir, regardless of his age. As Lord Grantham does not have a son, the estate should be divided between his three daughters or his two daughters and his granddaughter, Sybbie, Lady Sybil’s daughter, who represented her mother after her death in 1920. In the series, the entail prevents this division and drives much of the drama.

An entail could be used to prevent the division of a family’s lands between coheiresses by limiting who was eligible to inherit. Their most common use was to specify that only male heirs could inherit and therefore allow male collateral descendants (male descendants of younger brothers) to inherit instead of female direct descendants. This is the case with Matthew Crawley, who shares a great-great grandparent with Lord Grantham on his paternal line.

The entail is a familiar dramatic plot device in period drama and romance novels – think of how Pride and Prejudice’s Mrs Bennett is desperate to marry off her daughters as none of them are eligible to inherit Mr Bennett’s entailed estate which will pass to their cousin, Mr Collins. However, historically, entails served an important practical purpose in preventing estates from being broken up into shares, which could potentially be broken up repeatedly until nothing remained. When manors were divided between coheiresses they could lose their manorial status and privileges.

The Division of the Manor of Tremadart

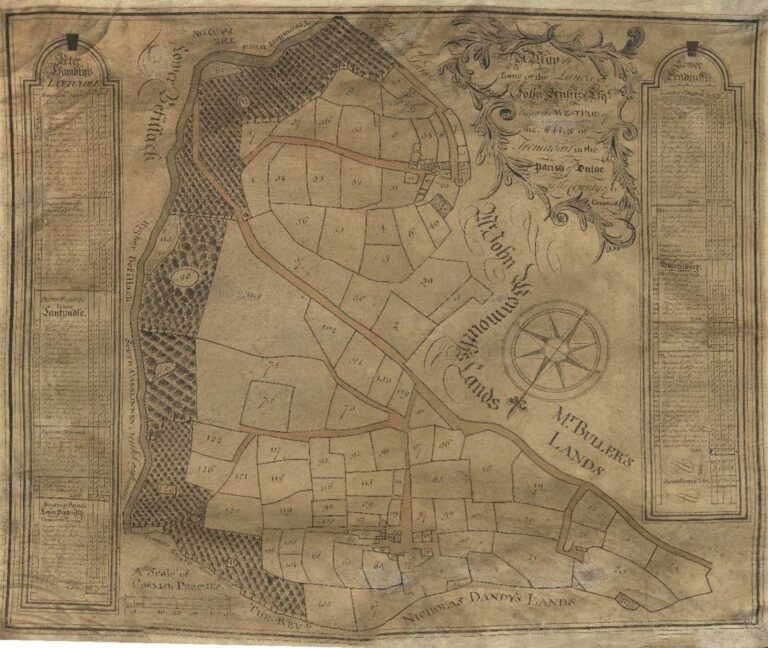

As mentioned, the Cornish manor of Tremadart, in the parish of Duloe near the popular tourist resort of Looe, was split into nine moieties. Tremadart Manor belonged to the Devon-based Huish family and was inherited by Emmeline, the daughter of Richard Huish and the sole heiress of her brother William.

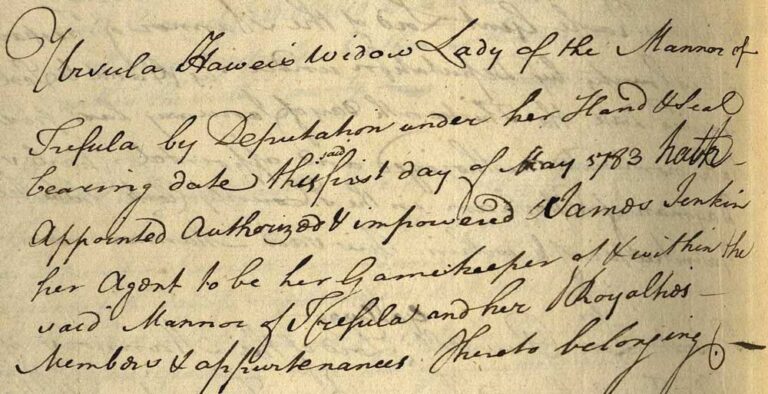

In 1388, the manor was seized by the crown when Emmeline’s husband, Sir Robert Tresilian, was executed for treason. However, as Tremadart was held by Sir Robert in right of his wife, Emmeline and her new husband, Sir John Coleshill, a wealthy London merchant, were able to successfully petition the crown to have the manor returned to them (Catalogue ref: SC 8/332/15777).

It may be that Sir John and Emmeline had formed an attachment or that Sir John saw an opportunity to rise in status and use Emmeline’s lands (which he would control during their marriage) to expand his wealth and influence, while Emmeline believed Sir John could use his wealth and court connections to ensure her inheritance was restored to her.

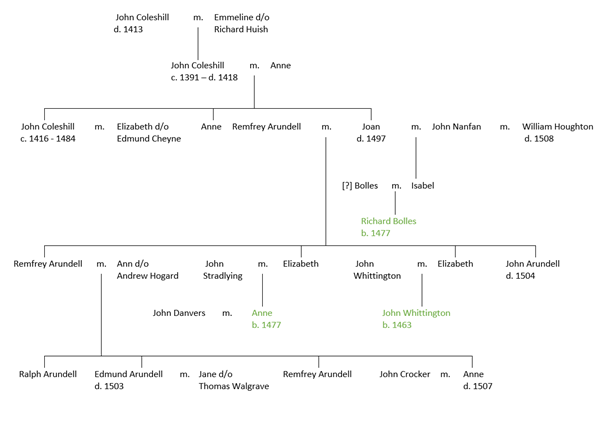

Emmeline and John’s son inherited but died shortly after his parents, leaving an infant son, also John, in the guardianship of John Arundell. Emmeline and John’s grandson proved his age in 1437 and married, but died without children. His sister, Joan, inherited the estates, which passed to her eldest son, Remfrey, and then his eldest surviving son, Edmund. Edmund’s heir was his only surviving sibling, Anne, as he died without children and his brothers predeceased him. Anne’s heirs were her aunts, Elizabeth, another Elizabeth, and Isabel or their representatives: Anne Danvers, John Whittington and Richard Bolles.

This information comes from the inquisitions post-mortem of Edmund Arundell and Anne Crocker. It demonstrates how difficult it can be to follow the descent of a manor. An inquisition post-mortem was used to determine what someone owned, what was due to the crown and who the heir or heirs should be. These documents, along with parochial histories, manorial documents, title deeds and wills are useful for tracing the history of a manor.

Eventually, the manor of Tremadart was reunited under a single owner, when three generations of a different branch of the Arundell family gradually bought the different parts from the respective heirs (see footnote 1). However, this was only after the Whittington part was further divided when John Whittington’s son, Thomas, died without any sons, and his estates were spilt between his six daughters (see footnote 2)!

Missing from the story

Marrying an heiress or coheiress allowed many Cornish families to acquire lands or wealth and climb the social ladder. The Morshead family took control of several Cornish manors, including Tresarrat and St Gennys when William Morshead married Olympia Treise, the sole heiress of her brother, Sir Christopher Treise (see footnote 3). Despite being an heiress, Olympia is not named in any parochial histories used to reconstruct manorial histories. It is recorded that the Morsheads inherited the manors, however, Olympia is referenced namelessly, as either the heiress of Sir Christopher Treise or the sole heiress of the Treises (see footnote 4). Her name, Olympia, is missing entirely from the records, and was only rediscovered by looking at family pedigrees in Burke’s Peerage.

What is also missing from historical records is Olympia’s emotions: her husband and son sold off the vast majority of the Treise family lands she had inherited. Once married, an heiress had no say in how her husband managed or disposed of the lands.

Alive, then dead, then alive again

When there was no male heir, there could be legal and other, sometimes violent, disputes over who should inherit. Richard Neville, the sixteenth Earl of Warwick, known as The Kingmaker, managed to gain control of the Dispenser and Beauchamp estates his wife, Anne, inherited from her parents, despite Anne’s half-sisters and their husbands also attempting to claim a share.

Such was the wealth and size of the estates, that after Richard Neville’s death at the Battle of Barnet in 1471, Parliament declared Anne legally dead so that her estates could be divided between her two daughters, Isabel and Anne. This meant their husbands – Edward IV’s brothers – George and Richard, could take control. Anne Beauchamp spent many years in the custody of her son-in-law, Richard III. However, after Henry VII won the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, Parliament declared Anne alive again and she was restored to her lands. In return, Anne gave several manors to the Duchy of Cornwall, including the Cornish manors of Helston Tony and Carnanton (Catalogue ref: E 40/11056).

A remarkable achievement

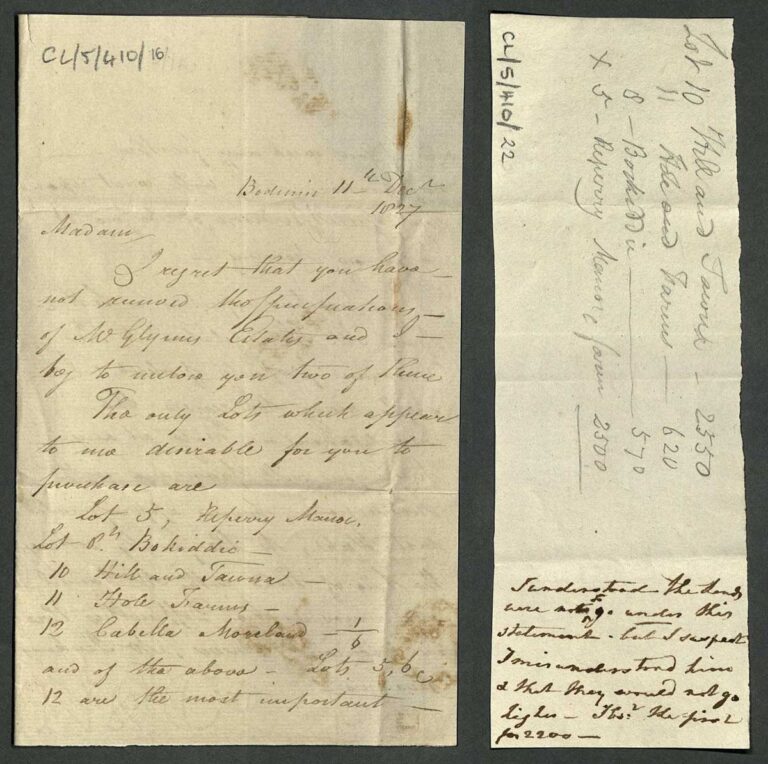

If the above examples suggest that heiresses could sometimes be little more than pawns, the story of Anna Maria (Agar) Hunt reveals a woman determined to make a go at it when faced with a tricky inheritance. In 1798, she inherited the Robartes family estates from her uncle, George Hunt, along with his substantial debts (Kresen Kernow CL 13/13). Unfazed, Anna Maria managed to turn around the fortunes of the estate by getting an Act through Parliament allowing her mother to sell another family house, Mollington Hall, in order to raise the funds needed to pay her uncle’s debts and run the estate.

Meticulous accounts and correspondence between Anna Maria and her stewards document the transformation of the estate and reveal that she was actively involved in the decision making. This must have represented a steep learning curve for Anna Maria at a time when wealthy women were more likely to be taught French and watercolour painting, rather than estate management. Her remarkable achievement meant her son, Thomas, could take over a thriving estate (see footnote 5).

An interesting custom

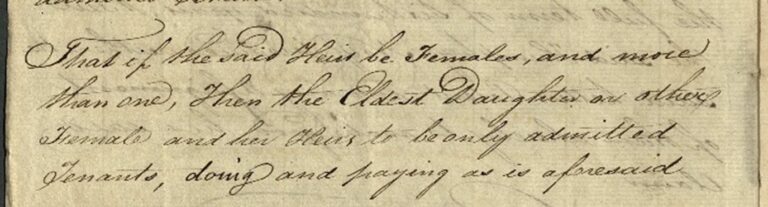

Occasionally, manorial customary law determines who inherits instead of English common law. The Parliamentary Survey of Duchy Manors taken during the Commonwealth period reveals a type of customary inheritance used in the Manor of Carnanton (see footnote 6). Contrary to English common law, in this manor, and several Duchy manors, a tenement or holding was not divided between coheiresses, but inherited solely by the eldest daughter.

Since January 2020, the update of the Cornish Manorial Documents Register has been underway. The register will list all manorial documents relating to Cornish manors and record where they are held. There will also be a manor history for every proven Cornish manor tracing ownership and descent.

The Manorial Documents Register for Cornwall is now live on The National Archives website and all manor histories will be available shortly for you to explore for your own stories of moieties and coheiresses.

Sources

D Lysons and Samuel Lysons, Magna Britannia Vol. 3, 1814

Paul Holden, Peter Herring, Oliver J Padel. The Lanhydrock Atlas, 2010

Norman J. G. Pounds, Eds. The Parliamentary Survey of the Duchy of Cornwall, 1982

Footnotes

- Lysons, D and S Lysons. 1814. Magna Britannica. Vol. 3. pp. 79-80. One of the sisters died without children so her share was spilt between her sisters making eight moieties to trace forward.

- Lysons, D and S Lysons. 1814. Magna Britannica. Vol. 3. pp. 79-80.

- Lysons, D and S Lysons. 1814. Magna Britannica. Vol. 3. pp. 112, 207-208,pp.xciii, 344.

- Lysons, D and S Lysons. 1814. Magna Britannica. Vol. 3. pp. xciii, 112, 208.

- Paul Holden, Peter Herring, Oliver J Padel. The Lanhydrock Atlas 2010. pp. 21-22.

- Norman, JG Pounds, Eds. The Parliamentary Survey of the Duchy of Cornwall. 1982. pp. 22-24.

Fascinating presentation of a complex topic, with such good examples.

Inheritance law was the background to so many family disputes when landowners used wills and trusts to try to provide support for younger sons and daughters, beyond the father’s lifetime, often imposing a considerable burden on the male heir. Chancery pleadings at TNA are full of such disputes.

The custom of female primogeniture (eldest daughter inherits when there are no sons, instead of splitting equally between daughters) was not restricted to the Duchy of Cornwall: a Warwickshire example is discussed in the TNA blogs https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/shakespeares-will-new-interpretation/ and https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/shakespeares-daughters-female-inheritance/

This is a fascinating exposition.

Can you describe the equivalent structure in Scotland please?

The title of this essay is “What is a coheiress?” and we are given excellent accounts and interpretations of coheiresses in respect of property. In addition there are coheiresses of heraldry and these have rather similar rules to those of property. The difference is that heiress rights to property usually vanish as the generations whizz by, as this article explains. But right to quarter arms do not vanish, they continue to descend down the generations. In 1900 or so there was an attempt to document the descent of heirs to the Nevill arms and at least 50,000 people were found who had inherited rights to those quarterings. Today that number will have expanded, possibly exponentially and there could well be 200,000 with those rights. And there are all the other arms whose quarterings have been inherited; it must be millions who have some rights to bear them.

Might is be useful to extend this article on heiresses and co-heiresses to include any inherited right to quarter arms?

I believe that Anne Beauchamp was declared “alive” again only if she gave up her inheritance to Henry VII. Her grandchildren were not able to inherit as a result.

Thank you, this is an excellent summary of very complex legal structures. I would note that Anna Maria Agar Hunt’s ‘remarkable achievement’ in making an economic success of her estates was by no means unusual. Bryony McDonagh’s Elite Women and the Agricultural Landscape 1700-1830 (2018) employed numerous case studies, and the collection Women and the Land, 1500-1900 (2019), ed. Aston, McDonagh, and Capern, explores women’s activity in land management across a wider social range.