On 16 January 2018 I wrote an introductory blog on the project to catalogue the series of records WO 416 consisting of an estimated 200,000 records of individuals captured in German occupied territory during the Second World War. These individuals were primarily Allied service men (including Canadians, South Africans, Australians and New Zealanders) but there were also several hundred British and Allied civilians and a few female nurses. Two years on, with the huge support of our on site volunteers, we have so far catalogued more than 110,000 records relating to individuals. This blog, the fourth in the series, focuses on the records of those held in Ilags.

Ilag is an abbreviation of the German word ‘Internierungslager’, meaning internment camps, which were used mainly for the confinement of enemy alien civilians. At one time there were more than 200 Ilags in operation in German-occupied France alone. Collectively they would house tens of thousands of nationals from a number of allied countries including the UK, Australia, the Netherlands, France, Belgium, South Africa, New Zealand, Canada and Scandinavia. Among the internees were more than 2,200 people resident in the Channel Islands. The German commander of the islands was ordered to deport to camps in Germany all British citizens not born on the islands. The collection in WO 416 currently includes nearly 900 civilians interned in Ilags, so there may be fewer than 2,000 in total when the project is completed.

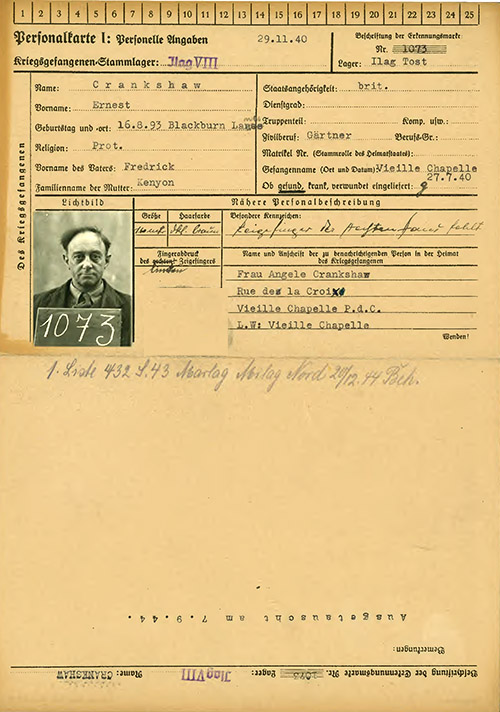

Ernest Crankshaw. Catalogue ref: WO 416/81/327

Record WO 416/81/327 consists of cards relating to civilian Ernest Crankshaw, who was captured at Vieille-Chapelle in France. Born in Blackburn in 1893, Crankshaw was one of a number of British gardeners working for the Imperial War Graves Commission who were interned following the fall of France in the summer of 1940. It is possible that he tended to graves at the nearby Vieille-Chapelle New Military Cemetery. From there, he was taken to Ilag VII in Tost, Upper Silesia in Poland, where he remained until his release in 1944.

The document FO 916/39 reveals, after a Red Cross inspection of Ilag VII in Tost in June 1941, that of the 1,200 internees housed there, 79 were scientists, 35 artists, 144 artisans, 273 merchants, 192 technicians, 149 agricultural workers, 109 operatives, and 232 sailors, mostly merchant seamen. The oldest was aged 72 and the youngest was 13.

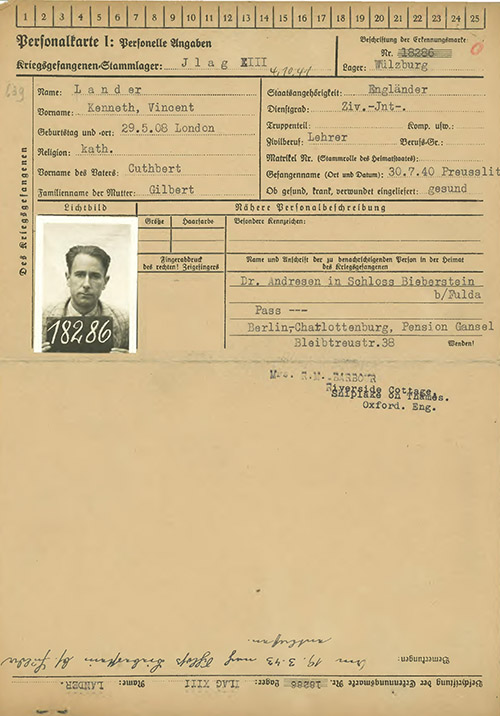

WO 416/215/426 contains the cards for Kenneth Vincent Lander, a teacher of English at a school in Bieberstein. He was captured in the village of Preusslitz on 30 July 1940 and interned in Ilag XIII in Wulzburg before being transferred to Ilag VIII at Tost on 4 October 1941.

Kenneth Lander. Catalogue ref: WO 416/215/426

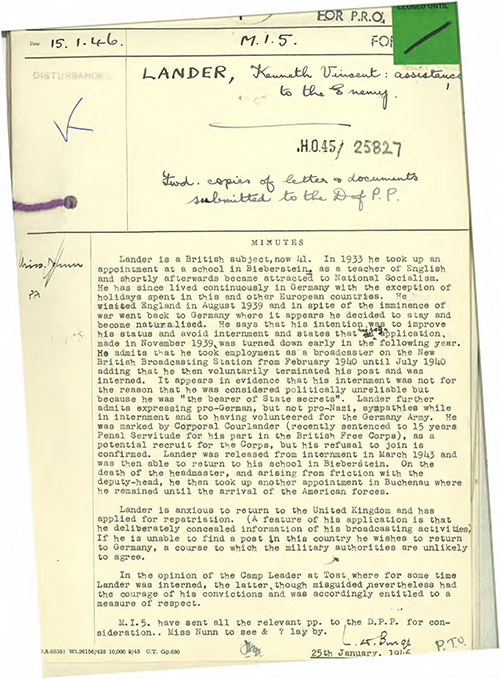

The document HO 45/25827 includes a record on Lander as a renegade and person suspected or convicted of assisting the enemy, compiled after the conclusion of the war. It reports that he had taken up the post of an English teacher at Bieberstein in 1933 and had become attracted to National Socialism, and had applied, unsuccessfully, to be naturalised as a citizen of Germany in November 1939. He then took employment as a broadcaster on the Nazi propaganda New British Broadcasting Station from February 1940 to July 1940, when he voluntarily terminated his post and was interned because he was ‘the bearer of State secrets’.

Kenneth Lander. Catalogue ref: HO 45/25827

While interned, Lander admitted that he was pro-German and had volunteered for the German army. He had refused to join the British Free Corps when he was approached by Roy Nicholas Collander, a fellow internee, after his release on 19 March 1943 when he returned to his teaching job in Bieberstein, and later in Buchenau, until the end of the war when he applied for repatriation to the UK.

This ambitious project will continue until the end of 2021 and for the main we are working our way through the series alphabetically by surname. This page, under ‘Arrangement’, provides a link to the projected completion stages of the project, subject to change.

Nearly 60% of the collection has now been catalogued by name of individual; we have loaded this information on Discovery so researchers can access the material on site or can arrange for digital or paper copies to be sent to them. We are offering a paid search service for uncatalogued pieces for those who do not want to wait until the project has completed: details of this service are available at piece level descriptions in Discovery. For example, if you were searching for records of a ‘Nigel Taylor’ then you would need to follow the paid search prompt at this link asking for a search in the piece WO 416/356, which will contain up to 500 records of individuals whose name is within the name range ‘Irvine Taylor’ to ‘William Taylor’.

Please note, unless proof of death is provided, records for those individuals born after 31 December 1919 will remain closed for 100 years, so records for those born in the year 1920 will become open on 1 January 2021. Of the 111,000 records catalogued, more than 90,000 are open to view.

‘The war behind the wire’ document display

To celebrate the project and dedication of the 24 volunteers working on it, we are staging a document display − The war behind the wire − on Friday 31 January between 14:00−16:00, where you can meet some of our volunteers.

If you’d like to read previous blogs focusing on other aspects of this important series of records, please click here and again here.

A great resource and a fantastic piece of work by the team.

The link between the Imperial War Graves Commission gardeners is very interesting and could be explored further with the help of the CWGC archives.

It might be a useful basis for a Keeper’s Gallery exhibition – although I realise these things take plenty of planning time, resources and a suitable time slot as well as possible tie-ins to merchandise in the shop.

Thanks for your comments, Richard. Yes, we are in touch with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission with regards to this collection, particularly around the cards relating to dead allied airmen, whose bodies were recovered on the ground. I agree, it would be nice to do a more detailed event or exhibition at some point, probably after the project concludes.

I knew Lander when I was an exchange student at Bieberstein in 1968. He invited me to tea together with another English boy, and my recollection is that, for some reason, Lander came out with the gem that “we never thought Jews could fight”. I rather spoiled the occasion by responding that the Israeli Army wasn’t doing badly. That put something of a damper on the occasion. He was well-known among the German boys for having been “Deutscherfreund” during the war, and was somewhat derisively referred to as “Knet” as a contraction of Kenneth, and very close to the German “Knecht”, essentially meaning a minion.