So the Opening up Archives programme is in its eighth month – we’ve passed the halfway mark and over half of us trainees have blogged here in our very own Trainee Tuesday slot. We’ve had posts on digital preservation, augmented reality, and we’ve learnt about projects and collections within our hosts’ archives, in Leicester Records Office and in London Metropolitan Archives. Oh, and we also learnt that one of our fellow trainees likes to masquerade as a frustrated 18th century spinster online. Well, to each their own.

A lot of collections we’ve seen so far are rooted in the 20th century onwards, but my traineeship goes back a little further than that. I and my fellow trainee, Amy, are based at the Borthwick Institute for Archives undergoing a traineeship that could easily be titled ‘learning to read really old things’. In fact that’s how I describe it to people who ask. Ours is the only traineeship which focuses mainly on these more ‘traditional’ skills: palaeography (the writing), diplomatic (the format), and Latin (the dead language).

And it makes sense really, when you think of the Borthwick’s holdings: an enormous collection of ecclesiastical records including parish registers, visitations, church court records, vast collections of diocesan records and probate records. Many of the documents we are interested in date back to medieval times. Don’t get me wrong, we do have records which date from – gasp – this century; we have a digital archivist and we even have a twitter account! However, in order for us to get anywhere in our traineeship we definitely need the skills we are learning.

In order for us to learn these skills we have to practice, and we’ve found that the best documents to practice with are Cause Papers and wills. The Cause Papers in particular feature a variety of English and Latin, follow a set format and often they can feature narratives which could rival a soap opera’s.

Transcription

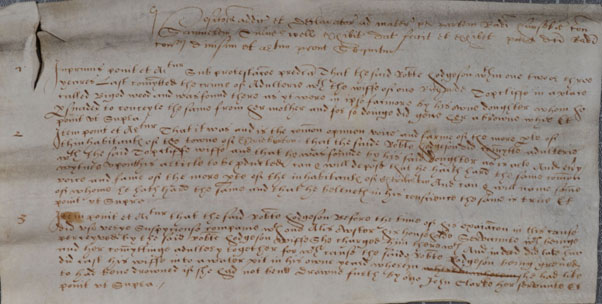

- In primis ponit et Articulatur Sub protestacioe predicta That the said Roberte Hodgeson within one two or three yeares Last commytted the crime of Adulterie with the wiffe of one Richarde Topcliffe in a place called Bigod wood and was found there as yt were in ipso facinore by his owne doughter whom he persuaded to conceyle the same from her mother and for so doinge did geve her a browne whie Et ponit vt Supra

- Item ponit et Articulatur That it was and is the common opinion voice and farme of the more parte of thinhabitants of the towne of Cherie burton that the saide Roberte Hodgeson did commytte adulterie with the said Topcliffe wiffe and that he was founde by his said doughter as is articulate And every wytnes upon this article to be producted can & will depose that he haith hard the same common voice and fame of the more parte of the inhabitants of Cheriburton And can & will name somme of whome he hath hard the same and that he beleveth in his conscience the same is true Et ponit vt Supra

- Item ponit et Articulatur that the said Roberte Hodgeson Before the time of his examinacon in this cause did use verye Suspyciouse companie with one Alis Auster his householde Servante which beinge perceyved by the said Roberte Hodgeson wiffe She charged him therewith And indeed did take him and her commyttinge adultery together for which cause the saide Roberte Hodgeson being greved did cast his wiffe into a water pit in his owne yeard wherein he had like to had bene drowned if she had not bene drawne furth by one John Clarke her servante Et ponit vt Supra

Once you get through the odd (odd to us, anyway) phrasing and spelling you get to the details: Robert Hodgeson was having an affair with Richard Topcliffe’s wife. His daughter sees this so he bribes her with a brown ‘whie’ – a cow – to keep quiet. His wife finds out anyway and in his anger, Hodgeson throws her into a ditch. I really do enjoy reading these documents for the glimpses you get into life at that time.[ref] 1. This paragraph was amended on 28 November – Robert Hodgeson was having an affair with Richard Topcliffe’s wife, not his servant. [/ref]

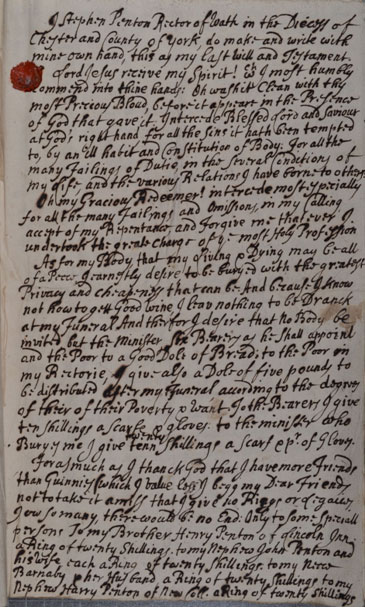

One of the bigger projects we are working on involves teaching a course to adult learners on documents and death, so wills will be featuring. The Borthwick Institute holds a large collection of wills (dating up to 1858), second only in size to the National Archives. Wills can offer us a glimpse of an individual; they vary in style but, especially in 16th to 18th century wills you tend to get a picture of the person writing or dictating their will. Look at this one:

Hopefully this is fairly easy to read without a lengthy transcription, but to start you off it reads: ‘I Stephen Penton of Wath in the Diocess of Chester and the County of York, do make and write with mine own hand, this as my last will and Testament.’ It then goes on in great detail on the subject of his soul and his repentance of his sins. Whereas at this time many wills would simply have ‘In the name of God Amen’ at the beginning, for this man this is much more than just a necessary religious preamble. This is a man devoted to God whose actions and wishes are determined through that devotion. I think it’s a great example of the individuality that can be seen in wills – it’s certainly why they are so interesting to me.

There are so many fascinating wills at the Borthwick, and indeed at The National Archives, and hopefully in coming posts I can show you more!

Great documents!!

Have I missed something?, but didn’t Roberte have an affair with the wife of Richarde Topcliffe and that is where the bribe of a white cow comes in and he had previously committed adultery with Alise Auster his servant.

Hi David,

You’re absolutely right, Robert was having an affair with Topcliffe’s wife, his daughter found out and bribed her with a brown ‘whie’ (an medieval word for cow). I didn’t proofread my post correctly – mistakes like this are all part of the learning curve of being a trainee I suppose!

Thanks for your post. It’s very nice to see and read about these documents. I think it was the wife that ended up in the water pit, sadly, after Robert became angry at her discovery of his adultery. The ‘s’ on ‘she’ is a bit obscured.