I am very privileged to be blogging to you today from a place to which I affectionately refer as ‘ground zero’. I mean, of course, the city of Leicester, much famed in recent weeks for a certain Yorkist monarch unearthed below the tarmac and asphalt of the county seat. Just 700mm below the aforesaid asphalt, mind you. This precarious state of affairs was compounded by the presence of 19th-century building foundations, drains and outhouses criss-crossing the ancient footprint of the 13th-century Franciscan friary in which he was laid to rest. Any one of these building projects could have easily swept away any evidence of Old Dick, and were indeed responsible for the unfortunate demise of his feet.

This fortuitous preservation, combined with the skill and luck that allowed University of Leicester archaeologists to pinpoint the grave’s location after opening only three trial trenches, is miraculous indeed. I am pleased and humbled to be placed in Leicester for my Opening Up Archives traineeship in this most landmark of years. All images in this article were personally digitised and it’s been wonderful to help preserve and promote such important source material.

But what exactly does the ‘Richard III Discovery Story’ have to do with archives, you may ask? In many ways, everything – because of course, our county Record Office holds the majority of desk-based data, in conjunction with the local Historic Environment Record office, which was used by resident archaeologists to surmise the circumstances of Richard’s burial.

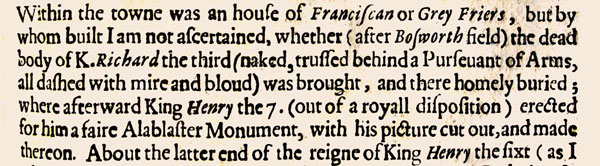

This includes historical documents written post-Bosworth, in which various people have described, recorded, and theorised about the King’s death and final resting place, as in this example below by William Burton in The Description of Leicestershire, 1622:

Extract from William Burton’s The Description of Leicestershire, 1622 (reference P 9/2)

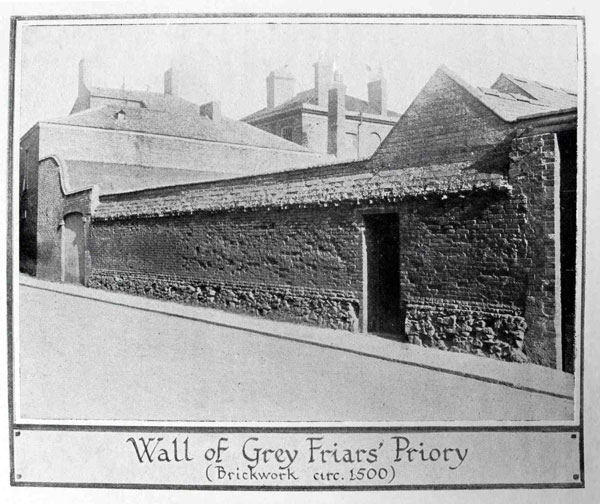

There were even 19th-century photographs showing parts of the friary walls still upstanding amongst the modern city buildings. This ‘Wall of Greyfriars Priory’ was located on the south side of Peacock Lane until its demolition in the 1920s:

Wall of Grey Friars’ Priory (reference P 9/4)

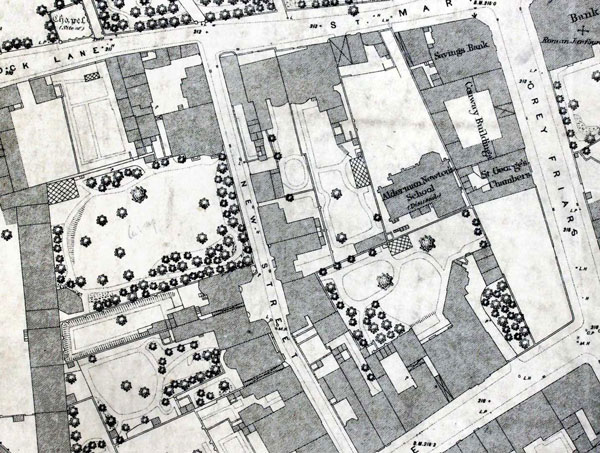

Perhaps most useful of all were the historic and modern maps, studied to provide cartographic clues as to the layout of Greyfriars and subsequent structures on the site. The stone foundations of the friary had been robbed out with staggering comprehensiveness in the era of monastic dissolution, blunting the effectiveness of archaeological resistivity equipment like Ground Penetrating Radar. Maps in this case became vitally important for determining target areas. Despite lacking blueprints for the friary itself, early modern maps indicated promising areas to explore, such as this 1741 example by Thomas Roberts:

Map by Thomas Roberts, 1741 (reference P 10/1)

It appears to mark the ruined mansion of Robert Herrick (as seen just above the text of Fryer Lane), a prominent Leicester citizen whose grounds overlay the former site of the friary. Christopher Wren, father of the renowned architect, noted in 1612 that Herrick’s garden included an inscribed stone pillar marking the site of Richard’s burial.

This 1885 Ordinance Survey map indicates still-open spaces in the Greyfriars area, especially the land to the left of Alderman Newton’s School, later to become a car park:

Ordnance Survey map, 1885 (reference P 10/2)

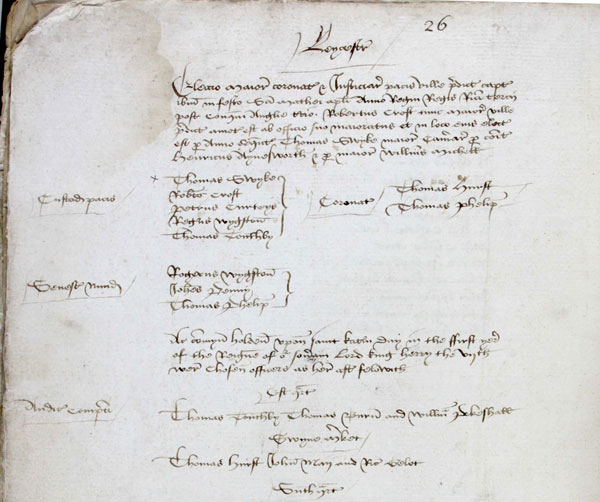

The treasures of the archives also provided a wider context for Richard’s life and death. A perusal of the Leicester Borough ‘Hall Book’ (a meeting record for the town government), for example, reveals no mention of the dramatic events surrounding Bosworth in its entries for 1485. It merely records the election of the mayor and officials in the third year of the reign of Richard III, followed by the same in Henry VII’s first year.

Extract from the Leicester Borough ‘Hall Book’ (reference BRII 1/1)

The Record Office also holds material relating to William Hastings, one of Richard’s closest supporters later executed for treason – interesting from both a historical and Shakespearean perspective.

William Hastings’ signature visible on a property deed relating to the Manor of Teigh in Rutland, 1472, with his seal on the far left

As a final note, I hope this brief tour of our holdings has demonstrated not only the important role played by archives in this momentous historical discovery, but also the continuing relevance of archives in all archaeological, historical, and architectural research.

I quite agree on the role of the archives and it was something that ‘Time Team’ used to do regularly but it seemed to be less and less than recreating some article (not that interesting!).

This is fascinating! Great to see all the contextual material too and a reminder of the value of such iconic archive documents – Thank you.

What was King Richards full name?