The Home Office Correspondence from the reign of King George III, held in record series HO 42, has been the subject of a long-term cataloguing project here at The National Archives. The documents themselves were microfilmed many years ago, and these films have been freely available to download from our website for some time, but the individual letters and reports in this series were not indexed, described or catalogued in detail before our project started, leaving them quite difficult to use.

Our hardworking volunteers have therefore been summarizing each letter within these volumes and adding the descriptions to our catalogue, Discovery. Their work is making it possible to search for subjects, names, events, ships and places, enabling researchers to bring together related material and find information otherwise buried within these difficult to read volumes of handwritten papers.

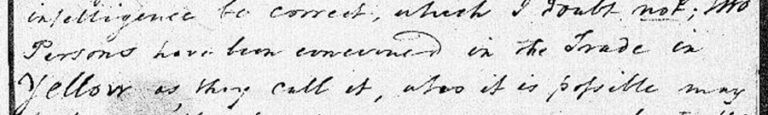

Our cataloguers have now reached the year 1811 (HO 42/111), and many interesting subjects and characters have come to light along the way. In looking for an example I came across a phrase that I had not heard before: the so-called ‘Trade in Yellow’. This was the fraudulent act of making and distributing fake money, also known as ‘coining’. Those who were caught spending fake money were convicted for what was known as ‘uttering.’ Coining was a major concern for the British government as can be seen from the number of times it crops up through the correspondence in HO 42.

For example, on 7 May 1810 the Home Office received a letter from William Digby, Steward to the City of Lichfield, about a petition on behalf of John Neve who had been sentenced to death for uttering several forged bank notes in Tamworth and Lichfield. Neve was from Birmingham where he worked in a linen draper’s shop, and because he had not actually made the notes himself, Digby felt that transportation (to Australia) might be sufficient to deter others from committing the same crime. But the authorities were adamant. Neve was hanged on 1 June.

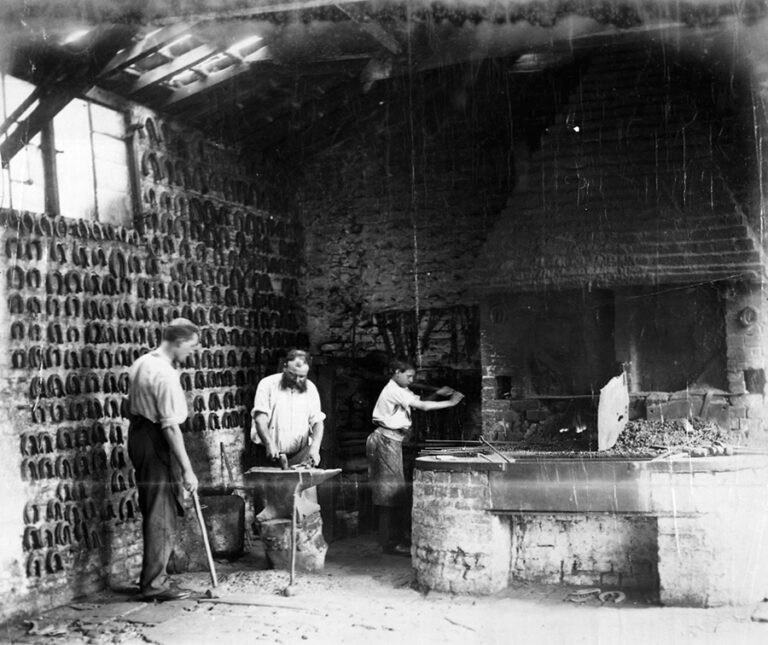

Fake coins could be created in two ways. One way was to ‘clip’ or file the edges from real coins and melt the pieces down into moulds to create new coins. This could be done by those whose trade gave them access to furnaces and the necessary equipment, such as blacksmiths, clockmakers and locksmiths, or metal workers. The second way was to strike, or stamp, new coins from pewter or copper using a die, and then rough them up a bit, and treat them with acid, to make them look like used silver coins.

The Home Secretary was open to suggestions on how to deal with the problem. On 18 June 1810 the Bank of England suggested that they might offer a substantial reward, along with a King’s pardon, to anyone giving information leading to the discovery of forgers.

In September a more devious approach was considered. Mr Powell, Assistant to the solicitors of the Royal Mint, wrote concerning two men involved in coining – one was a Scottish soldier in the Dumfriesshire Militia apparently named Crossfield, and the other was a prisoner named Jennings. Powell proposed to send bogus letters to Jennings purporting to come from his wife Mary, in an effort to discover the true identity of Crossfield. But in order to do this he sought permission from the Home Office to intercept any letters arriving at the Post Office for Mary Jennings. The scheme was turned down by the Home Office since Powell had apparently already taken adequate steps to secure any such letters by his own means, but the interception of letters by the Home Office was fairly commonplace, as can be seen from numerous examples from the records in series HO 33 – Post Office Correspondence.

At the other end of the country Isaac Head, a Collector of Customs in Helston, Cornwall, had noticed that gold coin was being purchased at an inflated price, and he believed it was being exported, naming Jacob Lyon as the guilty party. In the South East, the Reverend Pennington of Northbourne, Kent, (wearing his Magistrate’s hat rather than his dog collar) reported that certain people in Deal were buying gold in a suspicious manner, and at an ‘advanced rate’.

Meanwhile, down the road in Dover Mr Kelsey wrote from the Customs House concerning a man named Daly from Barbados who was apprehended on the fishing boat Alexander with 40 guineas and a small quantity of gold bullion on board. Foreign and English gold was thought to have been thrown overboard when the ship was boarded. Kelsey describes Daly as speaking like a foreigner and looking like a Frenchman. The case was forwarded to the Bow Street Magistrates.

In June 1811, Mr Tyler wrote from Witney in Oxfordshire complaining about the illegal trade in guineas and other gold coins. He offered to try to find out more information about this ‘Trade in Yellow’.

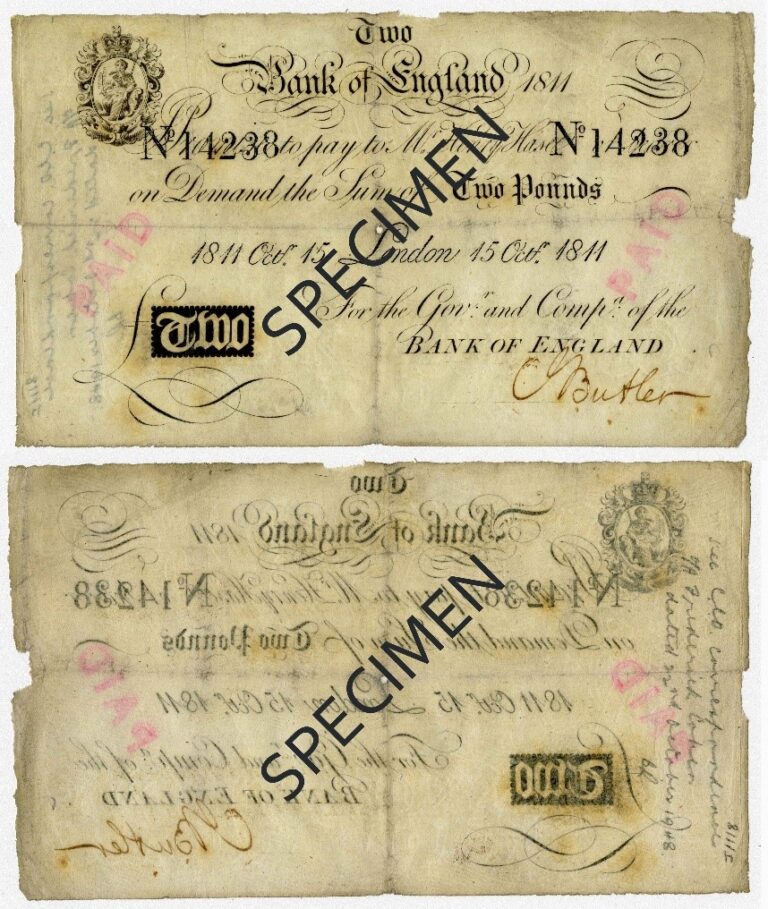

The problem was definitely an international one. In March 1811 a report had been received stating that two men were supplying materials to the Continent specifically for the purpose of forging bank notes. The Governor of the Bank of England (John Pearse) wrote in August 1811, regarding instances of bank note forgery in France. The Governor of the Bank of Paris, and the Minister of Police, Monsieur Clermant, were apparently very grateful to receive this information and, since only copies of the forged bank notes had so far been submitted, the French wanted to receive the originals to assist in the prosecution of the individuals concerned.

In return the French had supplied details of two Englishmen, Thomas Miller and John Moore, both of whom had been in custody at some point in France having offered to supply forged Bank of England notes. An example banknote dated 1796 was enclosed with their letter. The rest of the notes recovered from them, to the tune of £10,000, had been destroyed. Miller was believed to be planning to return to France, but the French were ready to arrest him when he arrived.

This correspondence about the Trade in Yellow was solely from 1810 and 1811, and no doubt there are earlier instances from earlier HO 42 boxes, with probably more to come as the cataloguing continues. Just one small subject, but with so much material. Why not try searching the series for something, or someone, who interests you? You never know what you will find.