Queer club culture in the 1930s was vibrant and varied, especially in the growing post-First World War underground scene. Music was central to the character of many of these venues, from the music hall artists of Billie’s Club to the expanding London jazz scene.

Particularly prominent among these unlicensed clubs was the Shim Sham, a queer-friendly jazz club described in Metropolitan Police records as a ‘den of vice and iniquity’[ref]MEPO 2/4494 – Shim Sham or Rainbow Roof unregistered clubs: bottle parties and sale of liquor out of hours, 1935-1938.[/ref]. The club originally opened in 1935 on Wardour Street in the heart of Soho, and from that point on it constantly attracted police attention. The club was heavily associated with African American culture, the name of the venue itself taken from the shim sham dance – a lively tap dance originating from Harlem, New York. The Shim Sham seems to vividly represent the ethnic and cultural diversity of London at this time.

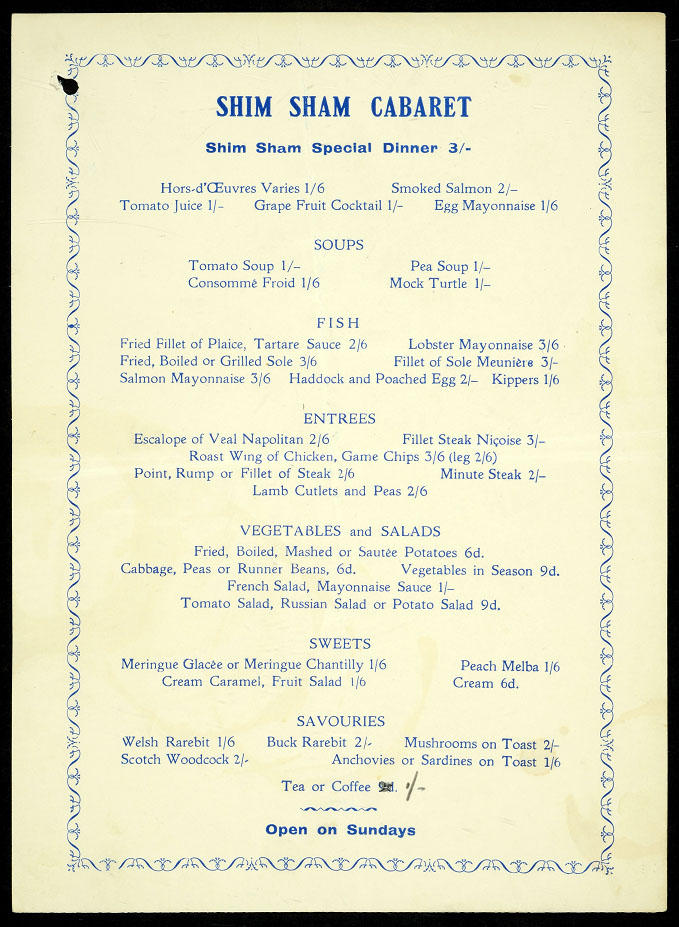

Image of a menu from the Shim Sham Cabaret, taken as police evidence in relation to unregistered clubs, bottle parties and sale of liquor out of hours, 1935-1938. Catalogue ref: MEPO 2/4494

‘London’s miniature Harlem’

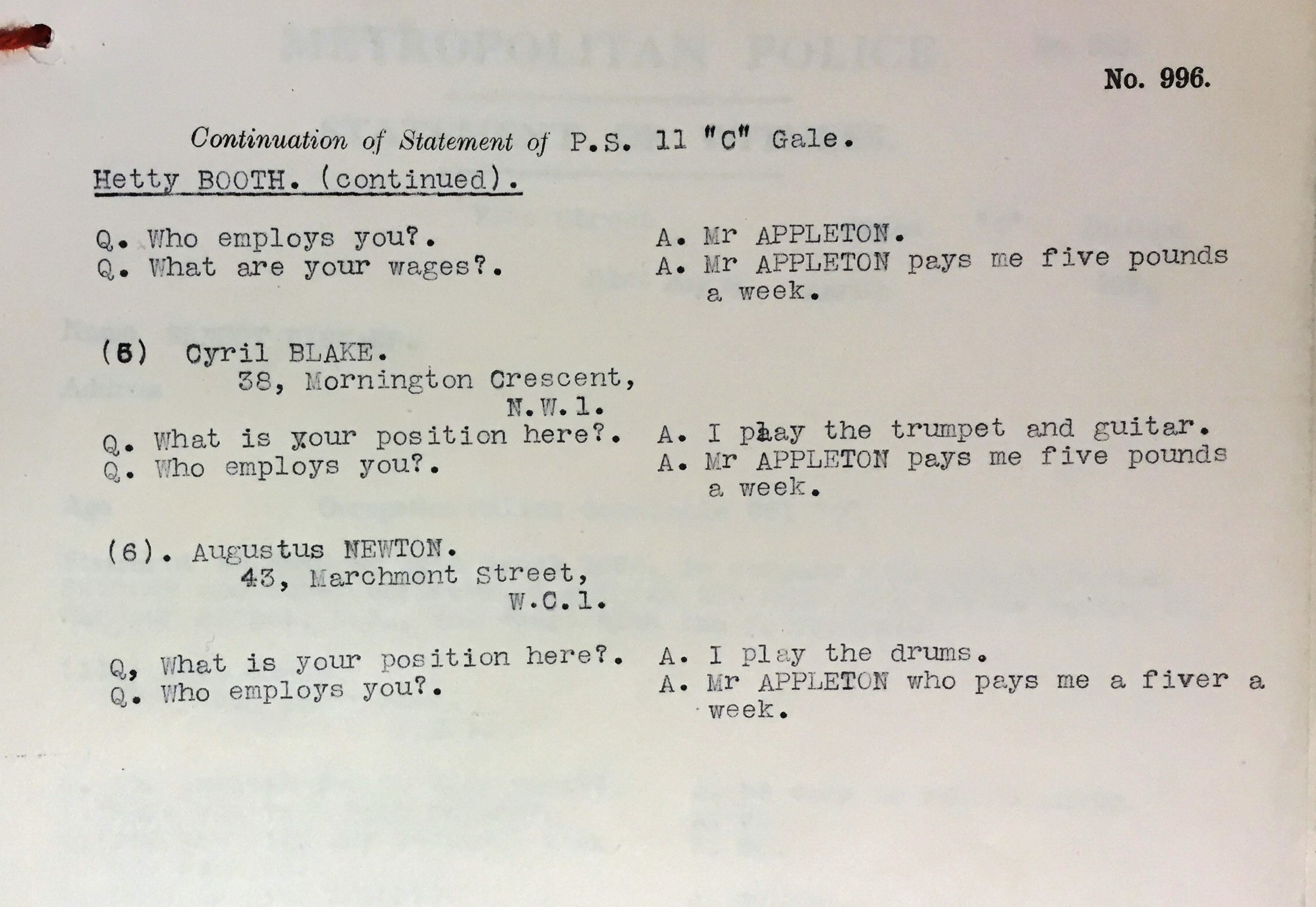

Described as ‘London’s miniature Harlem’, the Shim Sham was central to black jazz music in London in the 1930s, with a reputation for being the first to receive music from across the Atlantic. Bottle parties offered opportunities for new musicians to play and improvised jazz jam sessions were noted to take place in the venue. The police raids for liquor licensing give a snapshot of who was in the venue on this particular night; as well as Cabaret dancers there is Hetty Booth of the Palm Beach Stompers and Cyril ‘Midnight’ Blake, a Trinidadian jazz trumpeter[ref]Larry Kemp, Early Jazz Trumpet Legends (Rosedog Books, 2018)[/ref].

Hetty Booth and Cyril Blake being questioned by Police. Catalogue ref: MEPO 2/4494.

Music was key to the life of the club, which had a small elevated bandstand and a curved bar central to the space, with ample room for dancing. Undercover police observations noted that the dancing was of ‘an indecent manner’, with PC Alywn Stannard observing that ‘most of the couples appeared to derive sexual pleasure from the method of dancing’. Black British, Caribbean and African American performers utilised this performance space, which was in itself risky in an era of restrictions on American music performers in the UK[ref]LAB 8/1926 – Minutes of a deputation from the Agents Association, Entertainment Protection Association, Paramount Theatres Ltd and the Association of Ball Rooms and Dance Halls regarding admission of foreign bands to this country: decision to refuse permits to American bands and press communique, 1934-1961.[/ref].

The Shim Sham was also a space for radical politics, including pan-Africanism and anti-fascist meetings. Marc Matera noted that such clubs provided ‘sanctuaries from white hostility and, in some cases, as sites of political organising’[ref]Marc Matera, Black London: The Imperial Metropolis and Decolonization in the Twentieth Century (University of California Press, 2015). p.12.[/ref].

‘A den of vice and iniquity’

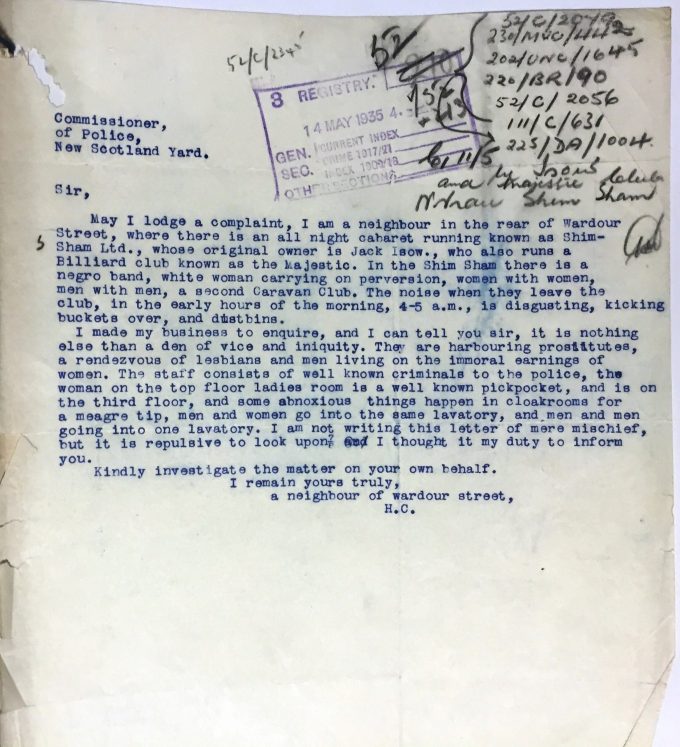

Public letters were repeatedly sent to police raising concerns around the morals of the club. A local resident wrote to the Police Commissioner signing themselves as ‘a neighbour of Wardour Street’ complaining that:

‘In the Shim Sham there is a negro band, white women carrying on perversion, women with women, men with men, a second Caravan Club.’[ref]The Caravan was a similar local club, just down the road, that had been raided on accusations it was a ‘disorderly house’ in 1934.[/ref]

These letters reflect the social climate of the time; even though same-sex relationships between women were never criminalised, they were not socially acceptable either. While we know women frequented such clubs and spaces in this era, they are rarely mentioned. However, this files does note women having relationships with other women, including a remark by police of two women entering the club, ‘both of the Lesbian type’.

Authors of such letters often used anonymous aliases, such as ‘An Englishman’, ‘A citizen’ and ‘pro bono publico’ (a Latin phrase meaning ‘for the public good’); this seems to be an attempt to take a moral high ground, drawing on themes of race, class and civic duty. Such letters increased police interest in these venues. The letter signed by ‘A citizen’ declares the Shim Sham to be a ‘rendezvous for homosexual perverts’, but the author goes on to make a return visit to the club.

Letter signed ‘a neighbour of wardour street’ in complaint to the Shim Sham. Catalogue ref: MEPO 2/4494

As well as the interest in queer relationships taking place in the club, the interracial relationships caused controversy. The venue took the position of welcoming a variety of patrons, both black and white. A police report by Stannard from June 1935 noted:

‘there was also about 20 coloured men present dancing with white women. Many of the persons present were drunk and I recognised many of the women present as prostitutes.’ [ref]MEPO 2/4494[/ref]

One letter noted, ‘the encouraging of Black and White intercourse is the talk of the West End’. The public outcry seems to be enhanced by the combination of perceived sexual ‘deviance’ and the varied racial background of the clubs clientele, leading to extra controversy and extra police attention.

Isow and Hatch

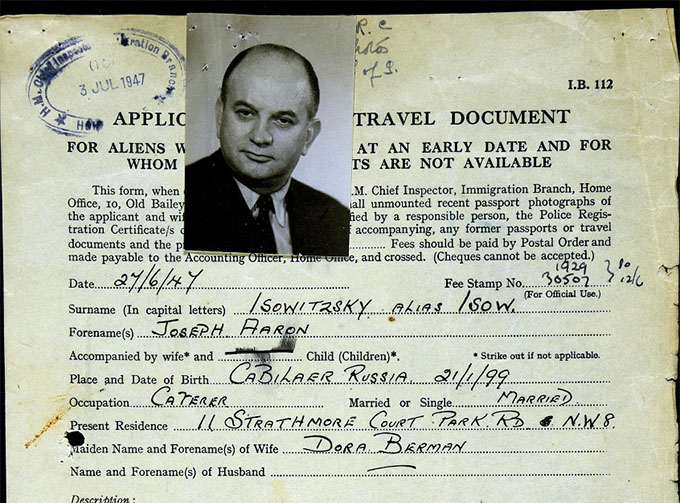

As well as the diverse clientele, the owners also attracted scrutiny. Jack Isow, known as ‘Flash Isow’, was a Polish Jew born in Russia. Isow was a renowned Soho club owner, and The Shim Sham was said to be bringing him a substantial £100 a week in profit. This was far from Isow’s only interaction with the police – he was later associated with gambling, police bribery and black market food-selling[ref]HO 405/24361 – Nationality and Naturalisation: ISOW, J A aka ISOWITZSKY Date of birth 21.01.1897.[/ref].

Photograph of Shim Sham owner Jack Isow, from his naturalisation papers. Catalogue ref: HO 405/24361

The other owner was the African American singer Isaac (or Ike) Hatch, who performed at the club. Hatch, originally from New York, settled in London in 1925[ref]Marc Matera, Black London: The Imperial Metropolis and Decolonization in the Twentieth Century (University of California Press, 2015). p. 48.[/ref]. Hatch served as the public face of the club, and was already a prolific figure on the London jazz scene, appearing regularly on the BBC, particularly in the popular Kentucky Minstrels show (a video of Hatch singing can be found here).

In 1933, Hatch was invited by writer Nancy Cunard to serve on the London organizing committee in support of the Scottsboro boys. The nine African American boys, aged between 14 and 22, had been wrongly charged with assaulting two white girls, which caused international campaigns in their defence. This underlines the political nature of the people involved with this space.

Bottle parties

While the venue caused controversy through its associations with black music artists, progressive politics and same-sex relationships, it was actually the club’s liquor licensing that originally gained it notoriety with the police.

Similar to many other clubs in 1930s London, the Shim Sham tried to avoid liquor licensing regulations by running as a so-called ‘bottle party’. Indeed, The Daily Express described it as the ‘first bottle party in London’. Such unlicensed clubs attempted to evade the law by claiming to run as a private party and offering alcohol on the basis that it was pre-ordered through wine merchants. This essentially avoided the restrictions of conventional licensing hours, aiming to attract punters around the clock.

Metropolitan Police records show concern in the rapid increase in bottle parties operating during this era, with a steady rise from 1934 onwards[ref]https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/results/r?_q=bottle%20parties&_hb=tna[/ref]. On 5 July 1935 undercover police first raided the premises of the Shim Sham on the grounds of liquor license evasion, and the venue was charged with operating as an unlicensed club. Ultimately they received fines totalling £200[ref]‘Bottle Parties At The Shim Sham’, The Times (London, 1935).[/ref].

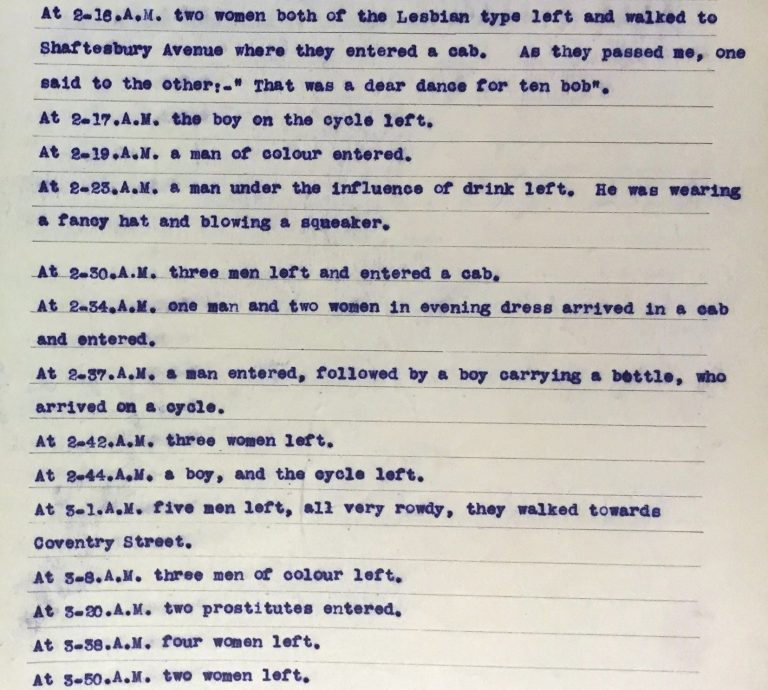

Photograph of a document noting police observations on the Shim Sham club, including a reference to ‘two women both of the Lesbian type’. Catalogue ref: MEPO 2/4494

The Rainbow Roof

After the 1935 raid the venue re-opened as the Rainbow Roof, and was subject to further charges of unlicensed dancing and music in May and June 1936. In a climate of police surveillance, clubs such as the Shim Sham had to be resilient to change. However, it is clear that there was continued demand for these venues, and this drove them to reopen.

The Shim Sham’s subversive mix of race, music, politics and sexual openness made it stand out to both the police and public. It can now be seen as progressive venue that has since been championed as a black queer space and a key source of new music.

My mum worked at Isow’s during the war when they had food stamps.

Food was always available at Isow’s for cash if you could pay.

She told me some very funny stories about the place.

My mum always brought her own food as Isow was very stingy to the staff as far as food was concerned. He went mad when he saw my mum eating a steak as he thought she was eating the restaurant’s food.

She was a beautiful lady.

My grandad Harry Blivas worked for Jack at the ace of clubs in wardour street, I think Jack was somehow related to my Nan Sadie, anyone who can shed more light on this or would like to have contact I would be very grateful

My mother Glen Panel worked for uncle Jack at Isow’s

Jack Isow was my grandmother Raie’s brother.She migrated to Australia in the early fifties. Any stories about Jack and his restaurant and life in London would be very appreciated, Steve Congdon, Kangaroo Island, South Australia, grandson of Raie Cheetham nee Isowitzsky.

Does anyone know of a club called the Ness club? My granddad was a black British performer and talked about it – a London club where all performers would hang out after shows.

I thought the club was called The Nest. My mother worked in the Shim Sham Club. owned by Jack Isow, `my mother and I sometimes used to go to his deli and he was always friendly.His deli was off Broadwick St near where the old Raymond’s Review Bar used to be.

Hi Mandy, I believe it might be The Nest club, owned by Ike Hatch, apparently it was on Kingly Street. Dancer Norma Miller mentions going after performing at the Picadilly Theatre in 1935. Does anyone know what number it was or what building it occupied? Thanks.

My grandfather ran a snooker club called the Q-club on the first floor above the Shim Sham in the 1930s and 40s

He used to box under the name of Mike Marsh and was also of Russian/Jewish descent.

My dad used to say he once went with his father to see the American vocal group “The Ink Spots” perform at the Shim Sham.

I’ve done a little research into the group’s activities but have never found any reference to the Shim Sham Club. I can only assume that, if my dad really did see the actual Ink Spots, it was probably only an informal appearance of some kind.

Can anyone shed any light on this?

Issac Flower Hatch married my grandmothers cousin, Midred Creed, my grandmother was named after her, she was Gertrude Mildred Creed, later Stickney, this was in USA, New York but we’re mainly from Connecticut. Mildred was a dancer and saxophonist with the Musical Spinners in Harlem and we believe this how they met. They were married May 11, 1921, seems he came to England in 1925 and never went back to the USA so I guess that’s technically when the marriage ended. Was following him to find more info on her, and came across the Shim Sham Club. Interesting read. Thanks

Oh wow this is all very interesting, my late father owned a business in soho since late 1960’s until around 2004…