Over the many thousands of years on this planet, we have looked to unravel the secrets of our ancient world and its people, from one period to another. From the world of archaeology, we have dug up some unimaginable things that we thought only existed in science fiction or in the film ‘Jurassic Park’, or even ‘Harry Potter’. But reading between the lines or from the margins of an old medieval ‘manuscript’, there are clues to our past that tell an amazing story of how life once was.

These ‘manuscripts’, as they were called, were the first stages in the development of the universal book we know today. Written by hand, in Latin, by the monasteries of the Roman Catholic faith. Manuscript writing produced some of the first prayer books used for services and psalms such as the devotional prayer books, the ‘Book of Hours’ and, of course, the sacred bible.

Manuscripts were also, very often, embellished with decoration to emphasise important passages or to enhance the meaning of text. Precious metals such as gold or silver and colour pigments were used for initials, borders and for small illustrations, and these works of art were known as ‘illuminated manuscripts’, which were produced in Western Europe between 1100 and 1600.

Illumination was a costly process, and was usually reserved for special books such as altar bibles or books for royalty and medieval manuscripts. Generally, and before the printing press, most manuscripts were written on parchment, either dried sheep or goat skin, and then bound into books called ‘codices’.

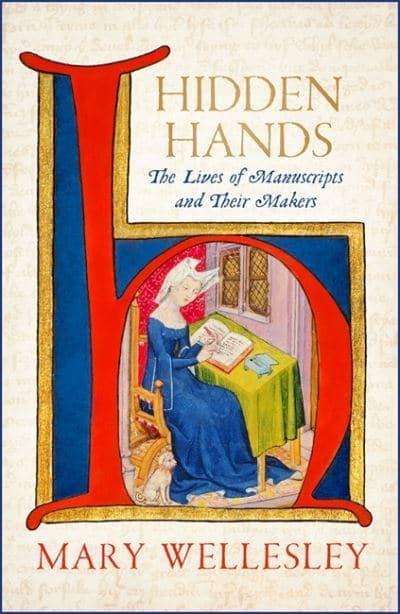

To understand the development behind these manuscripts, the book ‘Hidden Hands‘ tells the stories of the artists, scribes and readers and the people who made and kept these fragile objects that survived the ravages of time. It educates us on the history of both the English and the wider European cultures of language and literature, with examples from the Cuthbert Bible to works including those by Chaucer and Shakespeare, to name but a few. The book also explains the production and preservation of these priceless objects, with the emphasis on the early role of women as authors and artists.

Monks would also copy manuscripts by hand, not only for their religious works, but for a variety of other texts including astronomy, herbals and bestiaries; the latter being a collection of real, or imaginary, medieval animals which had connotations of sinful or moral characteristics, an influence emanating from the Christian faith. In fact, one of the most popular illuminated texts in northern Europe during the Middle Ages was the ‘medieval book of beasts’. The illustrations in the ‘bestiaries’ also influenced medieval art such as heraldry and carving in churches, in the forms of dragons, owls and pelicans; there were also mystical properties to stones and plants, that legends carry to this day.

Over the passage of time, bestiaries evolved into popular ‘illuminated romances’, which were mythological stories of chivalry such as the legendary tales of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. Songs, poems and folklore were also popular themes for the aristocratic readership, with religion becoming less so, as subject matter.

Overall, from the different periods of time and in different regions, the documented written evidence of human activity found in old manuscripts, even from clay tablets, scrolls and inscribed codices, enables us to understand the historical, ideological and cultural traditions from the past.

There are many examples of this in the book ‘Anatomy of a Nation: A History of British Identity in 50 Documents’ which describes what makes Britain unique, incorporating human stories from the past, alongside 50 documents; some recognisable, some not. There are many fascinating documents in this book, which if you read between the lines, metaphorically speaking, reveal the clues to hidden treasure from a time left behind.

As with many new and popular inventions, when the printing press arrived in England in 1476, it changed the way we received, transmitted and distributed information, leading to the decline of illumination. Illuminated manuscripts continued to be produced in the early 16th century but in much smaller numbers. However, they are, to this day, among the most common and best surviving specimens of medieval paintings and our history to survive from the Middle Ages.

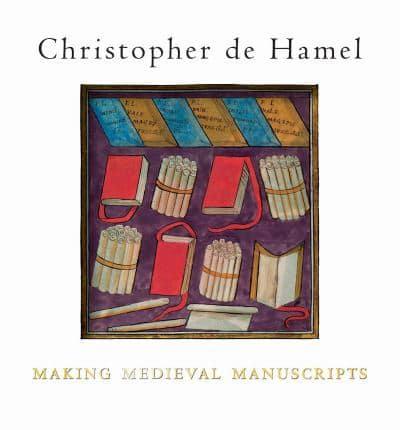

For those interested in studying manuscripts, ‘Making Medieval Manuscripts’ tells the story of manuscript production from the early Middle Ages through to the high Renaissance period. It describes each stage of production, the preparation of the parchment, pens, paints and inks to the writing of the scripts and the final decoration and illumination of the manuscript. It also comes with a technical glossary for terms relating to manuscripts and illumination.

All of the books mentioned in this blog are available to buy in the The National Archives shop.